Nyingma History of the Early Propagation of Buddhism to Tibet

Advent of Buddhism in Tibet

Central Tibet’s earliest exposure to Buddhism is ascribed to the reign of the twenty-eighth king Lha Totori Nyentsen (lha tho tho ri gnyan btsan; 374-493), although there may have been even earlier contacts in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands. However, the formal introduction of the Buddhist teachings coincided with the nine great religious kings who forged an empire in Central Asia between 629 and 848.

Some Buddhist texts were translated into Tibetan from Chinese, Khotanese, and Burushaski, but the vast majority of translations were made from Sanskrit sources, in two distinct phases, that are demarcated by the implosion of the Tibetan empire during the ninth century. The Nyingma tradition maintains the teaching cycles and texts that were introduced during the earlier dissemination, or ngadar (snga dar) at the height of Tibet’s imperial power. This is in contrast to the various so-called new, or sarma (gsar ma) schools (Kadam, Kagyu, Gelug, etc) that adhere to texts and teachings that were introduced during the later phase of dissemination, or chidar (phyi dar), from the late tenth century onward. An even narrower line of demarcation between the early and later phases of translation is sometimes drawn between the lifetime of the Indian scholar Smotijnanakirti (early tenth century) and that of the Tibetan translator Rinchen Zangpo (rin chen bzang po).

One sober account, written by the thirteenth-century historian Nelpa Pandita Dragpa Monlam Lodro (nel pa paNDi ta grags pa smon lam blo gros), asserts that around 433 CE certain Buddhist texts, including the Kandavyuha sutra and a text recorded under multiple names, including Pankyong Chagyapa (spang skong phyag brgya pa), were brought to Tibet by the masters Buddharaksita and Tilise from Khotan. At that time, Khotan was already an important oasis and crossroads for Buddhist teachers moving between India and China. Nelpa Pandita recounts how they returned to Khotan having discovered that no one could read or understand the meaning of the books.

Popular legends alternatively assert that these sutras along with the dharani of the Wish-Fulfilling Gem, dedicated to Tibet’s patron deity Avalokiteshvara, a mould engraved with the six-syllable mantra of Avalokiteshvara, and a golden stupa, all mysteriously landed on the palace roof at Yumbu Lagang (yum bu bla sgang). These objects were consequently given the name ‘awesome secret’ (gnyan po gsang ba) and were concealed because no one could understand their meaning. The king obtained a prophesy to the effect that the meaning of the awesome secret would be disclosed after five generations, and as an auspicious coincidence he was rejuvenated, living to the ripe old age of 120. His tomb is said to be at Dartang near the Chongye River, though others say he vanished into space.

The extant Tibetan translation of the Kandavyuha sutra is attributed to the scholars Jinamitra and Danashila, working with the translator Yeshe De (ye shes sde) during the early ninth century. The Tibetan version of the Pankyong Chagyapa is attributed to Tonmi Sambhota (Thon mi sambhota), in the seventh century.

It appears from other sources, such as Faxian’s records of Buddhism in Central Asia (dated 400 CE), that Lha Totori’s discovery of Buddhism was probably predated by Buddhist contacts in northeast Tibet, where the Tibetan Pu / Fu family formed the ruling house during the Earlier Qin Dynasty (351-394). The secessionist Later Qin Dynasty (384-417) is said to have offered patronage to the renowned Buddhist scholar Kumarajiva, and its rulers were well acquainted with the Buddhist teachings.

The Era of the Religious Kings

The thirty-third king, Songtsen Gampo (srong btsan sgam po), acceded to the throne in 629. He conquered the far-western kingdom of Zhangzhung and successfully unified the whole of Tibet for the first time in its recorded history.

Songtsen Gampo campaigned against the Azha T’u yu-un, an Altaic people who then inhabited the Amdo area of northeast Tibet, and skillfully reabsorbed the Sumpa pastoralists of the extreme northeast within the fold of the Tibetan empire. Then, following the Sui Emperor’s annihilation of the Azha around 630, the Tibetans (known in Chinese sources as Tubo) expanded into the northeastern borderlands to fill the vacuum, routing the remnants of the Azha as they went. Direct contact with Tang China was thereby established around 638. Lhasa became the capital of this unified Tibetan empire, and the original Potala Palace was constructed as the king’s foremost residence. In the course of establishing his empire Songtsen Gampo came into contact with the Buddhist traditions of India, Khotan, and China, and quickly immersed himself in spiritual pursuits, reportedly under the influence of his foreign queens.

According to some Tibetan sources the king abdicated in favor of his son Gungsong Gungtsen (gung srong gung btsan), but when the latter predeceased his father in 646, he resumed the throne. Tibetan influence during this period extended into Nepal and India, enabling the king, according to Tibetan legend, to send his able minister Tonmi Sambhota to India, where the uchen (dbu chen) script was developed from an Indian prototype to represent the Tibetan language. Internally he developed a legal code which was highly respected throughout the Tibetan world. Toward the end of his life the king abdicated a second time, in favor of his grandson Mangtsong Mangtsen. He passed his final years in spiritual retreat.

In the course of establishing his empire, Songtsen Gampo came into contact with the Buddhist traditions of India, Khotan, and China. He quickly immersed himself in spiritual pursuits, reportedly under the influence of his foreign queens Bhrikuti, the daughter of Amshuvarman, king of Nepal, and Wencheng, daughter of Tang Taizong, Emperor of China.

These queens are said to have brought as their dowry the two foremost images of Buddha Shakyamuni. The one that Bhrikuti introduced from Nepal was in the form of Aksobhya. The other one, in the bodhisattva form known as Jowo Rinpoche (jo bo rin po che), was introduced from China.

Moreover, when Princess Wencheng arrived in Tibet, she is said to have introduced Chinese divination texts, including the so-called Portang scrolls, and she encouraged the king to build geomantic temples at important power-places across the length and breadth of the land. These are revered as the earliest Buddhist temples of Tibet.

Tibetan geomantic temples were laid out, following an ancient Chinese model, according to four zones of imperial influence, corresponding to the central government, the royal domain, the zone of pacification, and the periphery of allied barbarians.

Just as China was conceived of as a supine turtle, so the Tibetan terrain was seen as a supine ogress, and geomantic temples were to be constructed at focal points on her body: the Jokhang (jo khang) at the heart, the four ‘district controlling’ temples on her shoulders and hips, the four ‘border taming’ temples on her elbows and knees, and the four ‘further taming’ temples on her hands and feet.

Some chronicles report that the actual number of temples constructed at this early period exceeded one hundred, but most sources confine themselves to thirteen. The immediate successors of Songtsen Gampo are said to have continued to build Buddhist temples, many of them including a central image of the Buddha Vairocana. Among them, Dusong Mangpoje (’du srong mang po rje; 676-704), the thirty-sixth king, is credited with the building of a temple at Ling in Eastern Tibet. Tride Tsugten (khri lde gtsug brtsan; r. 705-755), the thirty-seventh king, built the temple of Drakmar Keru, which can still be visited today in the On (’on) valley, north of Tsetang (rtses thang). His Chinese consort, princess Jincheng, is said to have established a short-lived community of Khotanese monks in Central Tibet, prior to her death in 739. King Tride Tsugten also married Nanamza, a princess of Tibetan aristocratic background, who gave birth to his son and heir in 730. Jincheng passed away in 739 when the bubonic plague devastated Tibet, and this, coinciding with conflict on the Silk Roads, seems to have provoked an anti-Buddhist rebellion in Lhasa. The king was assassinated by discontented ministers in 755.

Trisong Detsen (khri srong lde’u btsan), the thirty-eighth king (r. 755-797), built a royal temple near his own birthplace at Drinzang (mgrin bzang), shortly before his construction of Samye Monastery. Mune Tsenpo (mu ne btsan po; r. 797-804), the thirty-ninth king, established the temple of Karchung at Ramagang (skar chung ra ma sgang), near Lhasa, and Ralpachen (ral pa can; r. 815-841), the forty-first king, followed his example at Onchangdo Pemei Tashi Gephel (’on cang do pad+ma’i bkra shis dge ’phel), where he established a committee of translators, in order to standardize the Buddhist terminology of the Tibetan language.

Following the death of his father, Langdarma Udumtsen (glang dar ma u dum btsan), Prince Namde Osung (gnam lde ’od srung) revived this tradition of temple building at Jasa near Tsetang. There are several extant sites in Eastern Tibet – in Drayab (brag g.yab), Jyekundo (skye rgu mdo), Sershul and Minyag, among others – that attest to the final days of imperial patronage of the great religious kings of Tibet.

Buddhist Monasticism

King Tride Tsugten’s successor, Trisong Detsen, was perhaps the greatest of all the Tibetan kings, and it was during his reign (755-797) that Buddhism was formally established as the state religion. His early years were characterized by military campaigns against Tang China. The Tibetan army occupied the imperial capital Xi’an in 763, and the Zhol pillar was erected at Lhasa to commemorate this event. Increasingly, the king sought to promote Buddhism, which offered Tibet a system of universal ethical laws and spiritual values, and supported a rich core of learning in the classical sciences.

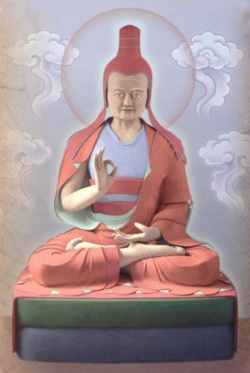

In order to establish monasticism in Tibet and pave the way for Buddhist civilization within his empire, King Trisong Detsen invited the Indian preceptor Shantarakshita to expound the teachings of the causal vehicles in Tibet and found a monastery at Samye, possibly in the year 779. He establishment of Buddhism as the state religion of Tibet, commemorated by an inscribed pillar at the entrance to Samye Monastery, was a threshold of enormous significance, in that the eclipse of Bon and the gradual demilitarization of the Tibetan world can be traced back to that event. When their objective was thwarted by obstacles instigated by hostile non-Buddhist forces, the king was advised by Shantarakshita to invite the ritual specialist Padmasambhava to participate in this endeavor. According to Nyingma tradition, it was Padmasambhava’s subjugation of the indigenous local demons on Mount Hepori that paved the way for the establishment of Buddhist monasticism in Tibet.

King Trisong Detsen, at Shantaraksita’s suggestion, ensured that the complex was modeled on the plan of Odantapuri Monastery, where the buildings themselves represented the Buddhist cosmological order, with Mount Sumeru in the centre, surrounded by four continents and eight subcontinents, sun and moon, all within a perimeter wall known as the Cakravala.

This construction would therefore come to symbolize the establishment of a new Buddhist world order in Tibet. Legends recount how humans were engaged in this unprecedented building project by day and spirits by night. Hence the monastery’s full name: Glorious Inconceivable Temple of Unchanging Spontaneous Presence (dpal bsam yas mi ’gyur lhun grub gtsug lha khang).

Shantaraksita was requested to preside over the ordination of Tibet’s first seven monks, the so-called seven men who were tested (sad mi mi bdun), namely: Ba Trizhi (rba khri gzigs), also known as Nanam Dorje Dudjom (sna nam rdo rje bdud ’joms); Ba Selnang (sba gsal snang), Pagor Vairocana, Ngenlam Gyelwa Choyang (rgyal ba mchog dbyangs), Khonlui Wangpo Sungwa (’khon klu’i dbang po srung ba), Ma Rinchen Chog (rma rin chen mchog), and Lasum Gyalwa Jangchub (la gsum rgyal ba byang chub). The king also established an integrated program for the translation of the Buddhist classics into Tibetan, bringing together teams of Indian scholars and Tibetan translators.

In 792, Samye was the setting for a grand debate held between Kamalashila, an Indian proponent of the graduated path to buddhahood, which emphasizes the performance of virtuous actions, and the Chinese monk (Hoshang) Mohoyen, a proponent of the instantaneous path to buddhahood, with its emphasis on meditation and inaction. Mohoyen was invited down from Dunhuang, which the Tibetans had recently conquered. According to most histories, Kamalashila emerged as the victor. However, according to other historians, such as Nubchen Sanggye Yeshe (gnubs chen sangs rgyas ye shes) and Nyangral Nyima Oser (nyang ral nyi ma ’od zer), the Chinese side was declared the superior teaching, albeit one that was unsuitable for Tibetans.

It appears that, around 797, King Trisong Detsen abdicated in favor of his eldest son, Mune Tsepo, who went on to establish regular Buddhist festivals at Lhasa and Samye. Though recognized as a lavish patron of Buddhism, Mune Tsepo is also known for having thrice attempted to introduce socialist measures, in order to promote equality between rich and poor, and on each occasion he is said to have failed. The king was soon succeeded by his youngest brother, Tride Songtsen (khri lde srong btsan; r. 804-815). Evidence suggests that the universal laws of Buddhist philosophy became increasingly important during this period, as an instrument of policy for the maintenance of the Tibetan empire in Central Asia.

Imperial patronage of monastic Buddhism reached its zenith during the reign of Ralpachen, who had each monk supported by seven households from among his subjects. He standardized the orthography of the Tibetan language and the terminology used in the translation of Buddhist texts, an achievement which has long stood the test of time. Politically, he managed to safeguard the borders of the Tibetan empire when confronted with the prospect of a Uighur-Chinese alliance in the northeast by waging a ferocious military campaign that resulted in the sack of Liangzhou and the signing of peace treaties with both sides in 821-823. Among them the treaty agreed with China in 823, which ranks as Ralpachen’s greatest achievement, clearly defined the Sino-Tibetan border at Chorten Karpo in the Sang-chu valley of Amdo. Obelisks were erected there and in Lhasa to commemorate this momentous event, the one in Lhasa surviving intact until today. A temple of atonement was also constructed in the border area where the conflict had been most severe.

However, the expense of conducting wars to secure the imperial borders, combined with decreasing revenue from the Silk Roads and the king’s generous patronage of Buddhism, often to the detriment of the older Bon tradition and Tibet’s aristocratic families, provoked an inevitable backlash. His elder brother, Langdarma Udumtsen, orchestrated a coup in 838. This resulted in the assassination of Ralpachen at the hands of Langdarma in 841; and with this act, the period of the great religious kings came to an abrupt end. The great empire, which they had forged, gradually began to implode under the pressures of economic insolvency and political disunity

By the late decades of the ninth century the Tibetan empire had disintegrated and nationwide patronage of the Buddhist teachings had ceased. Tibet entered what is traditionally known as the “dark period,” during which Buddhism in Tibet is supposed to have ceased to exist, or, worse, become irreparably corrupted. It is clear from the surviving accounts of the life of Nubchen Sanggye Yeshe that the teaching and practice of tantra did survive the turmoil of the age, in remote mountain retreats and isolated villages. Buddhist monasticism, on the other hand, could only survive in Amdo, the remote northeast of the country, where at Dentik (dan tig) and Achung Namdzong (an chung gnam rdzong) three far-sighted monks transmitted the Vinaya to Lachen Gongpa Rabsal (lha chen dgongs pa rab gsal), ensuring that Shantarakshita’s lineage of monastic ordination would eventually be reintroduced to Central Tibet and continue unbroken for the benefit of posterity.

Smrtijnanakirti, active most probably at the end of that century and in the early years of the tenth, is considered to have been the last of the early wave of Indian scholars translating texts into the Tibetan language. The new phase of translations that followed at the end of the tenth century, during the lifetime of Rinchen Zangpo (rin chen bzang po), still sought to conform to the standards established in the reign of Tri Ralpachen. However, whether they succeeded or not would become a matter of some contention.

Different texts and teaching cycles of much later Indian provenance were then being translated, and consequently different lineages of Indian origin began to take root in Tibet.

Authors: Gyurme Dorje and Jakob Leschly