On the view: the false dichotomy between dzogchen and mahamudra…

An old dharma friend named Jonny wrote me the other day with a question that he had. We had first met in 1995 down by Mungod in south India where he was teaching English at Drepung Loseling, and I was studying with Geshe Wangchen, under the kind graces of Lelung Rinpoche who at the time was dividing his time between Drepung Loseling and Nechung Monastary in Dharamsala.

Over the years as I came to meet and study under the late Kyabje Dorje Chang Bokar Rinpoche, and my path crossed with Jonny’s and other dharma friends amidst the annual groundswell of dharma that occurs during the fall months in Bodh Gaya. It was there that I had the opportunity to introduce Jonny to this wonderful oceanic meditation master. From that point onwards that my relationship with Jonny changed to that of dharma brother, which is where we are in this moment.

After the tragic, unfortunate death of Kyabje Dorje Chang Bokar Rinpoche, most of his students were left in a place of loss and sadness. The confounding suddenness of his death created a barren confusion- I remember from my own experience that this was a terribly painful and confusing time. The loss of a teacher can be very painful. I had felt that there was an intimacy in my relationship with Bokar Rinpoche that made him feel like a father- it took a number of years to be able to return to his seat monastery in India without feeling a profound sense of loss and sadness.

Over time the, winds of karma, the great teacher that might be described as the impermanence of appearance, blew Jonny into the lap of Yangthang Rinpoche, and I into the lap of H.E. Gyaltsab Rinpoche. As our experiences arising from meditation practice change, and as we slowly try to blend whatever insights that arise from such experiences into our daily lives, we email from time to time- to check in and see where the other is.

In an email last month, Jonny wrote:

I have a question arising from the Tsele Natsok Rangdrol book I’ve just finished reading. He mentions the “traditions of practice of the different lineages – recognising the meditation from within the view or establishing the view from within the meditation”. This has provoked a lot of interest in my mind, and I keep coming back to it. As far as my very limited understanding is concerned, the first approach in this quote seems to be that of Dzogchen, and the second Mahamudra. The Kagyupas seem to talk more about meditatione Nyingmapas focus more on the view. In mahamudra there seems to be more emphasis on shinay and then lhaktong in order to realise the view, while in Dzogchen it seems to be more about instantaneously, effortlessly seeing what is already there. And this seems to fit with what I said about the quotation above.

Am I on the right track here? Can you comment on the quotation for me? Or can you recommend a book which illuminates clearly m’mudra and dzogchen and the differences?

Upon reading this email, I put down what I was doing, and with a deep sense of joy and excitement, considered what he was asking. What an important question- what wonderful subtlety implied in this question!

At first glance I tend to feel that there is a distinct “stylistic” difference between mahamudra and dzogchen in a way. On an ultimate level, however, there is a false dichotomy between view and meditation. This is something that Tsele Natsok Rangdrol touches on in the book The Heart of the Matter. Rangjung Dorje, the 3rd Karmapa, in his wonderfully succinct Mahamudra Aspiriation Prayer, and Karma Chakme, in The Union of Mahamudra and Dzogchen support this perspective.

In the Tibetan tradition there is often a reference to the term definitive meaning (nges don) which generally translates as: ultimate meaning, ultimate truth, truth, objective meaning. Definitive meaning exists separately from relative meaning. Relative meaning refers to the comparing and contrasting between things, it is a means through which we can know and understand one thing from another. The experience of definitive meaning- ultimate truth- occurs in some combination of gaining clarity of relative truth. In the experience of resting within our mind as it arises, within our experience of the arising of phenomena/appearance, we are afforded glimpses of the definitive meaning. It is a process of familiarization, and in some cases even described as a homecoming of sorts; the reunion of the mother and the child.

I sometimes gain some clarity in viewing both mahamudra and dzogchen as something akin to mathematical sets. They are two ways to approach the realization of mind, the definitive meaning of its experience, and the various qualitative ways in which we experience “mind”. These two unique sets, mahamudra and dzogchen, are distinctive incredibly rich paths that undoubtedly lead to the experience of a definitive meaning, an inner vocabulary, of our experience of mind. This “mind” that we experience, is the same for both “systems”, and when we look at their differences, they often seem to drift into the misty edges of mind essence.

Both approaches recognize that experiencing the mind’s essential nature is an experience akin to a mother being reunited with their child; or something similar to realizing that we have been carrying a priceless jewel with us through out our life experience, but failed to notice it- until now. That noticing, that knowing awareness, and the inner confidence which arises announcing awakening. In fact, the mere suggestion of there being an awakening, or a change in our being, draws us out of relationship with the experience of mind in a definitive manner.

Both mahamudra and dzogchen describe the freshness and immediacy of our experiences- they are now. Not something planned for the future, not based upon trying to recreate a past experience. This experience is often described as clear, blissful, and empty. These four words are translations from the Tibetan, and what they truly mean for us within our own experience, is unique to our own particular journeys. Some experience more of the illusory aspect of mind, others experience the mind’s clarity, and still yet others experience the bliss associated with resting within definitive meaning.

Bliss can be very dangerous and seductive, not to mention hypnotic. I have spent much time with patients who have been admitted to locked in-patient psychiatric facilities who struggle with bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia; people who in the throes of their mania exert phenomenal enthusiastic energy in trying to convey the perfect experience that they feel. Oh, how the bliss lit their soul ablaze in a way that nothing else could. The feeling that I am often left with when with such patients is that of awe and respect- I find it very compelling to be allowed to witness the expression of their experience of blissfulness that often occurs within the experience of mania. I have often found myself hypnotized while in the presence of such people, dazzled by the passionate feeling of blissful unity- and yet I am left feeling a profound sadness that I experience while trying to chaplain patients who appear addicted to a sense of bliss that disconnects them from the rest of the world.

Bliss arises, and we are taught to not be attached to it- it is one of the many things that we may experience.

And yet, bliss is important.

Similar shadows exist around the experience of mind as illusory. Indeed, the profound experience of the emptiness of all phenomena as experienced through our interface with the illusory appearance of every moment- a joining with the totality of what arises as empty of all characteristics and the awareness of the interplay between ourselves and this field of experience- holds the danger of being overly reductive. It’s shadow may be a depressive state.

Bliss, emptiness, and clarity/luminosity- these are three ways that we experience mind.

Yet, mind is mind is mind is mind…. and yes, just as there can be distinct aspects of the mind that we relate with, or experience, and just as there is a particular style, or even flavour, that is distinct regarding dzogchen and mahamudrae must remember that these distinctions arise from mind. We feel and think, and yet from where do these feelings and thoughts arise; these created worlds, what is their source? We interface with different aspects of mind, but they are temporary appearances, waves lapping at the edge of a lake- no two are the same, and there is no end, they just happen. To hold onto the distinction may be problematic.

I tend to wonder if we can say that these distinctions have more meaning outside of our personal experience of mind, than say, as opposed to within our individual experience of mind. The three masters that I refered to above, Rangjung Dorje, Karma Chakme, and Tsele Natsok Rangdrol all occupied places within their practice traditions as Kagyu/Nyingma masters and the two former masters were recognized as tertons in their own right. All three were able to hold both: mahamudra and dzogchen. They were able to come into direct relationship with mind. From this place, I wonder if all distinctions around how practice is described, or how mind appears/in experienced is secondary. While I feel that it is safe to say that individually we may all exhibit a predilection towards experiencing glimpses of the definitive experience of mind somewhere within the traditional nomenclature of bliss, emptiness, or clarity, with one aspect perhaps feeling more “natural” than another, it seems important to recognize that our experiences change, and that it is possible to form an attachment to the way we experience mind-essence.

For example, usually our relationship with our yidam has something to do with the way in which we interface with the experience of awakening as each yidam offers a model/modality through which we can act seated within our experience of buddha-nature. I marvel sometimes how much we really become our yidam (or they become us)- in many ways it seems that there is a profound transference of quality and of action within the modalities of expression through body, speech, mind, and essence. At our best, there is an experience of natural simultaneity, a natural ease and effortlesness in which we are the yidam- in moments where practice feels forced and contrived, we get hung up on the details, on experiencing things only one way, that there is a specific way in which we have to practice, a way that we have to interface with appearance. All of the sudden we are working to get some where, to be something, or to induce a particular experience. In yidam practice there are handy “tricks” through which we return to focusing upon the implements or mandala of the buddha of our practice, or a quality, or the transparency of our visualization so that an antidote of sorts is applied to falling out of relationship with our experience of the yidam; that which is no other than us.

Similarly, in approaching mahamudra from the perspective of shinay, lhaktong, and their union, a structural path laid out by the polymath Jey Gampopa, and as passed on from him down to the 9th Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje in the Ocean of Definitive Meaning as well as Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche in his essentialized distillation of Wangchuk Dorje’s seminal work, entitled Opening the Door to Certainty, yes, there may be more emphasis placed upon “establishing” or perhaps “easing” into the view through meditation. This approach to mahamudras termed the Path of Liberation, or sometimes refered to as sutra mahamudras methodical and graded- often a gradual path, but not always so. And I feel that much thought must be inserted here. As dharma practitioners, or anyone really who follows a particular spiritual tradition, textual exegesis is vital to the maintenance of tradition- it is what connects us to the group, to our lineage. And yet, we must realize that the exegesis that we interface with surrounds the way we experience mind, which ultimately ends up being a relatively individual experience. That the Path of Liberation can only be said to be a gradual path ignores the fact that the possibility of “instantaneous” realization is always a present- in fact instantaneous insights do occur. Karma Chakme spends time treating this particular “problem” as it were. For him spontaneous realization is always a possibility, no matter what the practice may be.

Then there is the Path of Means, often refered to as mantra mahamudrar the approach to mahamudra through the six yogas and or inner and secret yidam practice. In these approaches there is often a more instantaneous type of resting in the view, something that I feel offers a similar feeling of sudden realization that dzogchen often refers to. I guess you could say the Kagyupa have bridged both sudden and gradual; Gampopa introduced the first Lam rim literature into the Kagyu lineage and from that point in time it appears that Sutra and Mantra mahamudra was presented as separate approaches to realizing the mind’s essential nature. Peter Alan Roberts in his recent book entitled Mahamudra and Related Instructions, describes just how distinct Gampopa’s work was in codifying the Kagyupa approach to mahamudrad how often the delineation between gradual and instantaneous approaches, especially in the associated forms of sutra and mantra approaches was made along the lines of monastic and lay. As the first person to translate much of the core essence of the early kagyu lineage into a monastic tradition, a split had to be made between some of the tantric practices that challenged the conduct maintained by the monastics and his lay followers.

I suppose what I am trying to stress is that I’m not so sure that looking for the difference between the View as described within the context of dzogchen and that of mahamudra is as helpful as modulating between both Views within our practice. The View helps keep meditation fresh- it is necessary to be familiar with the View (how the mind arises). Meditatione process of developing familiarity with the View (putting it into practice and actualizing it) prevents the View from becoming a concept that appears more real and rigid than perhaps it ought to be. There is a binary relationship that we need to maintain, a relationship that shifts and eventually blends into a naturalness in which there is no longer any applied effort- we just are. Some of us have been lucky enough to meet people who manifest being in this way- they are indeed buddhas.

The false dichotomy lies within the fact that there is no real difference between meditation from within the view and the view from within the meditation. The View is mind-essence, the mind as it arises, as it appears, and how we relate to appearance. Meditation is resting within that experience of mind. Even the practice of shinay carries all of the aspects of mind. What is the stillness? What is it that we are we focus upon in a single pointed way? Where is the stillness? True, asking these questions is similar to lhaktong, and indeed may be, but that knowing, that awareness, is always there while we do shinay- it is not necessarily something that we add to the mix. As far as literary exegesis is concerned there is a lineal distinction between the approach to mind as we find in mahamudra, lamdre, and other forms of practice, however when we look at the works of great realized siddhas we find descriptions that offer resounding clarity. For example, Rangjung Dorje says:

Free from being mind-made, this is mahamudra;

free of all extremes, it is mahamadhyamaka;

this contains all, and so is “mahasamadhi” too.

Through knowing one, may I gain firm realization of the meaning of all.

Great bliss with no attachment is continuous.

Luminosity without grasping at characteristics is unobscured.

Nonconceptuality that goes beyond intellect is spontaneous.

May unsought experiences occur without interruption.

Preferential grasping at experiences is liberated on the spot.

The confusion of negative thoughts is purified in the natural expanse.

Natural cognizance adopts and discards nothing, has nothing added or removed.

May I realize what is beyond limiting constructs, the truth of dharmata.

And Tsele Natsok Rangdrol follows:

The Middle Way, the unity of the two truths beyond limitations,

Mahamudrae basic wakefulness of the uncontrived natural state,

And the Great Perfection, the original Samantabhadra of primordial purity-

Are all in agreement on a single identical meaning.

This mind that is present in all beings

Is in essence an original emptiness, not made out of anything whatsoever.

By nature it is unimpeded experience, aware and cognizant.

Their unity, unfathomable by the intellect,

Defies such attributes as being present or absent, existent or nonexistent, permanent or nothingness.

Spontaneously present since the beginning, yet not created by anyone,

This self-existing and self-manifest natural awareness, your basic state,

Has a variety of names:

In the Prajnaparamita vehicle it is called innate truth.

The vehicle of Mantra calls it natural luminosity.

While a sentient being it is named sugatagarbha.

During the path it is given names which describe the view, meditationd so forth.

At the point of fruition it is named dharmakaya of buddhahood.

All these different names and classifications

Are nothing other than this present ordinary mind.

With these words as a guide, we find our way, succeeding and failing to realize the nature of mind- working to familiarize ourselves through practice with mind and with phenomena. As we settle into natural awareness, an effortlessness in being, I wonder where all the words go. Perhaps they too, dissolve into the soft edges of graceful wakeful knowingness.

As part of my CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education) training with the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care we have been exploring aspects of Jungian psychology especially as it relates to symbols and images. We recently finished a great week of classroom experience which included a conversation with Morgan Stebbins, the Director of Training of the Jungian Psychoanalytic Association, a faculty member of the C.G. Jung Foundation of New York, and a long time student of Buddhism. Stebbins’ presentation on Symbol and Image was dynamic and quite moving- he embodies a depth and conviction that I find compelling. In addition to this, Stebbin’s visit to our class came at a point when I’ve been playing around with writing a blog post about sacred geography. Very timely indeed.

“What does sacred geography have to do with me?” one might ask. I would answer, “Everything”.

Within the framework of Buddhism geography and therefore pilgrimage, has come to be something of an important phenomena. Certainly this is not anything unique to Buddhism; we have a tendency to want to return to places that are significant for us. Sometimes there is spiritual significance, sometimes it is societal, and most often it is interpersonal. An example of these would be making the Hajj if you were Muslim, perhaps visiting Washington D.C., or taking your children there so that they could appreciate the way that our nation governs itself, and perhaps the place where one’s parents were born, or where they died. Geography allows us to honor the meaning that we value in our lives. We live within time and space, and within the latitude and longitude that time and space afford us, we intentionally (and even unintentionally) plot the course of our lives and identities within their dynamics. How many times has a particular season or even date reminded us of an event that occurred in the past around the same time? My root teacher passed away on Christmas eve over a decade ago, and I am always reminded of that great loss whenever Christmas approaches. On the other hand, the Fall months feel like a time of rich growth for me- they always have, and for some reason these months continue to prove to be significant for me. These are two examples of how I plot meaning within my experience of time.

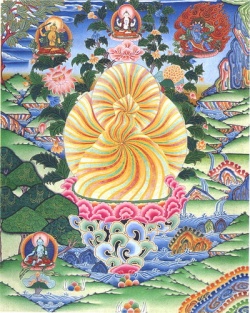

In most faiths pilgrimage has become something that one engages to touch the past; it is a means to feel the link of those who have come before us and charge the present moment with their power. It can be the Wailing Wall, St. Peters, the Kabba, Bodh Gaya, a sacred mountain, river, the ocean, a tree and it can also be imagined- something symbolic, a living pulsating image such as a mandala.

According to the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the Buddha predicted that students of the path would visit the place of his birth, his enlightenment, where he first taught, and where he would die. He stressed that this may be something that one does if they want to, if it brings meaning, inspiration, and context to their path. It was a suggestion, not a directive, and ultimately a very insightful reading of how we relate to time and space.

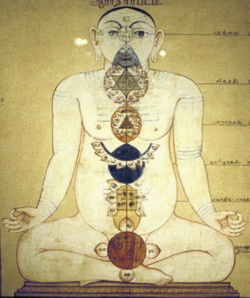

Within Vajrayana, or tantric Buddhism, pilgrimage appears in a more visionary manner. In addition to the four major sites associated with the Buddha’s life, various pithas, or ‘seats’ (places of power and meaning associated with the dissemination of Buddhist tantra) became included into various lists of sacred places. For example, there are twenty-four pithas throughout the Indian sub-continent that are associated with the places where the Buddha revealed himself as Chakrasamvara and taught the cycle of Chakrasamvara and related practices. The pithas, while relating to actual places, also correspond to places within our bodies that have an internal energetic significance. The exact location of these pithas vary from tradition to tradition, but there is a relative constancy of the mirroring of external and internal meaning in relation to these sites. In some ways, and according to some teachers, pilgrimage can be done without ever leaving where you are as all of the major pithas exist within the matrix of our energetic body. This approach is touched upon by the Buddhist Mahasiddha Saraha who in once sang:

This is the River Yamuna,

This is the River Ganga,

Varanasi and Prayaga,

This is the moon and the sun.

Some speak of realization having traveled and seen all lands,

The major and minor places of pilgrimage.

Yet even in dreams I have no vision [of these].

There is no other boundary region like the body;

I, virtuous, have seen this for good and with certainty.

Stay in the mountain hermitage and practice self-restraint.[i]

This could be considered the more essentialist approach to pilgrimage and sacred geography; wherever we are, we are sitting on the vajrasana under the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya. I feel that this is a great place to be. This approach is excellent. However it can be important to recognize that we are constantly changing, and that there will sometimes be times when we don’t feel connected in that essentailist kind of way. What then? Well, then there is the benefit of pilgrimage. One could go to a place of significance to try to touch upon the inspiration that such places offer us. But perhaps, they may not have to be in India…

In his book Sacred Ground, Ngawang Zangpo has addressed in a very detailed manner the thoughts of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye on the importance of sacred geography. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye lived in Tibet from 1813 to 1899. He was a famous meditation master of the Kagyu, the Nyingma and Sakya Lineages. Through his wide and open attitude Kongtrul helped define and spread the Rime, or non-sectarian view of the dharma, in response to a general atmosphere of sectarianism amongst all schools of Buddhism in Tibet at the time. He was a compiler of termas (revealed treasure teachings) and was a terton (treasure discoverer) in his own right. A real renaissance man, Kongtrul not only helped shape and preserve the Kagyu lineage, but all forms of Dharma in Tibet.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye identified a variety of places in Tibet as reflections of the twenty-four pithas in India. This change in perspective had the effect of being quite dynamic in that it placed Tibetans directly in the center of their own world of sacred geography. Of course some brave souls still made the journey to the twenty-four pithas in India, but many visited the sites that Kongtrul and his dharma friends Chokgyur Dechen Lingpa and Jamyang Kheyntse Wongpo felt were equivalent. For some, this type of translation/re-orientation was too much; indeed the great Sakya patriarch Sakya Pandita took issue with the possibility that several pithas could be located in Tibet.

Sacred Ground is an excellent book for exploring the thoughts and teachings of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye on the subject of pilgrimage and inner spiritual geography. Ngawang Zangpo translates Kongtrul Rinpoche’s Pilgrimage Guide to Tsadra Rinchen Drak [or Pilgrimage Guide to Jewel Cliff that resembles Charitra (the union of everything)]- an amazing text that treats in great depth the nature of that particular pilgrimage location as well as it’s inner and secret significances as it relates to various energetic centers found throughout the body. Zangpo includes a chart listing the manner in which the pithas correspond to the body according to the Chakrasamvara tantra, an appendix that includes three fascinating texts one by Kongtrul and Khyentse Wongpo, one by Chokgyur Lingpa, and a compiled list of sacred sites in Tibet by Ngawang Zangpo. Of particular interest is a reference to a note found in Mattheiu Ricard’s translation of The Life of Shabkar:

It must be remembered that sacred geography does not follow the same criteria as ordinary geography. Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-91), for instance, said that within any single valley one can identify the entire set of the twenty-four sacred places. Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche (1903-87) also said that sacred places, such as Uddiyana, can shrink and even disappear when conditions are no longer conducive to spiritual practice. The twenty-four sacred places are also present in the innate vajrabody of each being. (p.442, n.1)

A similarly fascinating book on this subject is the collection of essays edited by Toni Huber entitled Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture. These essays offer a rich exploration of issues surrounding pilgrimage sites, sacred geography and geomancy. Of particular interest is the essay by David Templeman entitled Internal and External Geography in Spiritual Biography in which he explores the relationship that the mahasiddha Krishnacharya with the twenty-four pithas, especially that of Devikotta. Templeman considers the importance of these sites as internal locii and suggests that while pilgrimage to these sites was indeed important, there is little evidence to support that many siddhas visited all of them. In fact, Templeman suggests that some sites more than others are of particular significance and have been over time, while others are dangerous, home to subtle harmful beings (wild flesh eating dakinis) that need to be appropriately tamed before one can occupy that particular location. In the case of the mahasiddha Krishnacharya, his untimely end occurred at the site of Devikotta, as this site had a reputation for incredible unpredictable volatility that was well known throughout India at the time.

I tend to wonder where this place of volatility, with beings that need to be subjugated, resides within me. A three paneled chart provided by Templeman in his article listing the twenty-four pithas according to the Chakrasamvara Tantra, the teacher Jonang Taranatha and the Sakya master Kunga Drolchok, indicates that Devikotta -this very powerful site- is located within my energetic body around both of my eyes. I wonder where it’s mirror locations are?

What I find most compelling about these books, and this subject in general is that it has a lot to do with how we relate to the world around us, how we import meaning to this world, and what we allow of ourselves in being in relation to time and space. The essays in Huber’s book and the work by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye describe both the Tibetan cultural, as well as the general vajrayana approach to sacred geography- these two are not by all means identical as Huber points out in his essay. Huber suggests that Tibetan culture influenced vajrayana making it distinct from the Tantric Buddhism that developed in India which then spread to Tibet. While the distinction is subtle, it speaks to how meaning is translated. It is arguable that there can never be a one-for-one translation of a text from one language to another, and perhaps, a one-to-one translation of a religion is similarly unlikely. That said, without straying into the soft edges of hermeneutics, I would like to wonder out loud, “How does Buddhist sacred geography translate to Buddhism in the ‘West’?” I think that a great response to such a question is, “That’s a silly question, Buddhist sacred geography is as present in the west as it is in Tibet or India”. I’d also add that we should map it, live within it in a more open way, and make it ours.

If Jalandhara is a site that corresponds to the crown of my head, Oddiyana a site that corresponds to my right ear, and Devikotta my two eyes, all the while representing sacred places reflected upon the Indian Sub-continent and or the Tibetan Plateau, where would they be reflected upon the geography of the United States for example? Or more playfully perhaps, Brooklyn? It seems that some of this has to do with fully owning and bringing vajrayana home. In so doing, I would love to see how this type of re-orientation occurs. Can we do for ourselves what Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye did for Tibetans?

As Buddhism takes root here in the U.S. and continues to flourish I would love to see all of the twenty-four pithas of the India subcontinent reflected here. Perhaps as we learn to slow down and notice our relationship with our surroundings this will be more evident. I’m very curious to see how this aspect of vajrayana in particular translates to western culture; it seems like there is great potential.

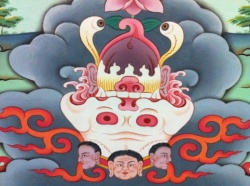

I remember very clearly the cold late November afternoon in Gangtok, Sikkim, fifteen years ago when I was taught Milarepa guru yoga. It was one of those incredible experience of being shown something for the first time: electrifying, new and magical. One of the things that instantly spoke to me about the practice was the imagery of the inner offering of the five meats and five nectars that appears in the beginning of the text. Indeed, in looking back at it I think that the inner offering in Milarepa practice (as well as in many other tantric Buddhist practices) has been something that has held great meaning for me. Part of it may be the fact that this prelude to Milarepa practice is a wonderfully clear metaphor for Mahamudra; one of the central forms of meditation passed down through the Kagyu Lineage. The inner offering presents a different form for approaching the mind’s essence from other meditations- chod involves cutting and offering, samatha/vipassana is quiet and still, some practices involve fiery wrath, others still, a warm familiar tenderness. Each of these emotive backgrounds illustrate a modality, an emotion, a style, or an outlet through which we may we express and experience ourselves within the context of awakened activity; the union of clarity of being and luminosity of mind. Within the context of the inner offering, the metaphor is that of boiling and melting (not unlike the athanor which refines the prima materia in Alchemy). This burning and melting is so powerful that a sublime blissful nectar is produced, a non-dual nectar that confers the blessing of the Buddha. This part of Milarepa (2006 film)|Milarepa]] guru yoga came to be, and remains, an exciting fun part of my practice, instilling a sense of dynamic power that seems to illustrate the potential “atomic” nature of Vajrayana.

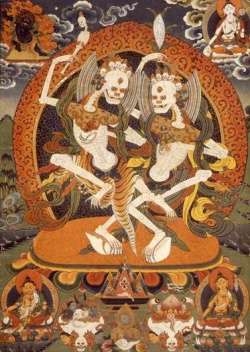

The inner offering is a product of medieval India (roughly between the 6th through 12th centuries), when both Tantric Buddhism and Tantric Hinduism were taking shape. This was a time of immense social upheaval throughout the Indian sub-continent. In both Hindu and Buddhist circles, groups of siddhas broke away from the orthodoxy of their respective majorities in order to develop, practice and teach tantric forms of Hinduism and Buddhism. One of the principal causes of such a move was a the adoption of an antinomian attitude towards the strictures of Indian society with its caste system, its brahmanic tendencies towards “purity”, and the establishment of Buddhist monasteries so large and wealthy that their leading teachers often lived very comfortable lives of scholastic celebrity. This shift was often exemplified by the lives of the 84 mahasiddhas, some of whom left their teaching positions at the famous monasteries of Nalanda, Somapuri, and Vikramashila to practice in jungles, others were kicked out for their outlandish behavior, while a few were kings or princes and princesses afraid to give up their wealth, and many were of low-caste status. Disregard for the religious and cultural status quo led to a shift towards the charnel grounds as gathering places, frightening “dirty” locations, where wild animals scavenged the remains of the recently dead. It was a time where meditation instruction was sung in vernacular so that the everyday person could be touched, not just those who were ordained or occupants of a higher social station. This time also marked a focal shift (as far as practice goes) towards cities where the concentrated hustle and bustle of everyday life revealed itself as a ripe field of opportunity, a place where one is faced to deal with a full range of emotions. For some it was also a shift into the seductive luxurious courts of both major and minor royalty. Human experience, in all of its forms was recognized as embryonic in nature allowing most anyone who exerted themselves in practice to become pregnant with realization. This became the birth right of all, not just those born into one caste, and certainly not just those who were literate or educated. Perhaps one could go so far as to say that this period was a time of spiritual anarchic-democratization.

One of the most interesting aspects of this time period was the apparent looseness of sectarian divisions between the then Saivite sub-sects that represented the forefront of Hindu tantra and the Buddhist equivalents who ushered in Chakrasamvara, Hevajra, Candamaharosana, Guhyasamaya and other early tantric deity practice. The shared iconography between Saivite Kapalika Hindu tantra and Buddhist tantra is clear evidence of some common direction and praxis orientations. Such symbolism makes use of skulls, flayed animal and human skins, invocations of the more wrathful nature of these deities, and sexual union with their consorts. Similarly, the dual identities of the siddhas Matsendryanath, Gorakanath, Jalandhara, and Kanhapa who are counted as four of the eighty-four Buddhist mahasiddhas as well as founders of the Hindu Nath lineages suggests that there was much more dialog between the more iconoclastic progenitors and practitioners of Hindu and Buddhist Tantra. These four siddhas are credited with the development of Hatha Yoga, which has many applications within Buddhism and Hinduism. David Templeman, in his fascinating paper Buddhaguptanatha and the Survival of the Late Siddha Tradition has suggested that the interaction between Buddhist and Hindu yogins was more common than most Tibetan scholars had assumed. This was a perplexing and fascinating subject for the erudite Tibetan scholar Taranatha, and according to Janet Gyatso, in her book Apparitions of the Self, the great Nyingma terton Jigme Lingpa was very curious about such points of contact. In some way it appears that the assumption of difference seems to be a convenient projected organizational tool used to try to clarify such a difficult topic of study. A way to try to define that which tries to defy definition. The Centre for Tantric Studies offers a forum for exploring the history and development of tantra in and around the Indian Sub-continent.

Much debate and uncertainty surrounds the issue of how tantra came into being, even more debate surrounds how we should approach understanding tantra. The works of scholars like Geoffrey Samuel, Roger Jackson, Ronald Davidson, David Gordon White, Elizabeth English and Christian Wedemeyer (to name a few) have helped to illustrate some of the more pertinent issues surrounding the subject of Buddhist tantra.

They are melted by wind and fire.

As a means of throwing open the gates of ultimate realization, the Pancamakara: madya (alcohol), mamsa (meat), matsya (fish), mudra (edible foods) and maithuna (sexual intercourse) were included in Hindu tantric rituals as a means to effect a eucharistic understanding of non-duality. In essence, by consuming that which is culturally regarded as impure in ritual context, one undermines the very notion of the purity/impurity dualism that keeps us trapped in feeling fragmented and lacking expansiveness. These particular objects, when handled and offered by practitioners of this more radical form of Hindu Tantra were held with the left hand, the hand reserved for handling impure substances. In adopting an enthusiasm and greater equanimity towards these violations of cultural mores regarding cleanliness (spiritually as well as otherwise) one was directly contradicting the rules of conventional Hinduism. It should be noted that the use of the left hand in offerings is also prevalent in one form or another in Buddhist Tantra. This dynamic was central to the Kapalika sect whose influence upon the corpus of Yogini Tantas was considerable. While few scholars can agree who influenced who, the most important thing is that these traditions arose.

Light from the three seeds attracts wisdom nectar. Samaya and wisdom become inseparable and an ocean of nectar descends.

In Buddhist sadhanas the five meats and the five nectars share a certain equivalency to the Hindu Pancamakara. Rather than the transgressive five M’s (madya, mamsa, matsya, mudra and maithuna) we have the five meats: the flesh of cow, dog, horse, elephant and man, and the five nectars: semen, blood, flesh, urine, and feces. The five meats are representative of the five skandhas: form, feeling, discrimination, action, and consciousness. Likewise, the five elements: earth, fire, wind, correspond to the five nectars. Depending on the explanation lineage of the inner offering, these associations may vary, but generally the essence is the same. In this practice we join the five wisdoms with the five elements to produce a non-dual intoxicating ambrosia that has the capability of revealing the qualities of awakening and in that sense provides a powerful spring-board of potential realization. In other words we are joining our perceptions with the objects of our perceptions- entering into direct relationship with phenomena; uncontrived and expansive. We boil perceptions and the ability to perceive in a five dimensional way thereby naturally releasing our habitual confused samsaric reaction for a more aware equanimous relationship with the world around and within us. This is the very mechanism of samsara/nirvana! What’s more, as this mechanism unfolds, it reveals the don-dual vastness of Dharmakaya, a spring-board for sacred outlook. For a moment everything is okay, relaxed into ease.

These substances emanate from their specific syllables and are brought together to be mixed in a kapala (skull cap bowl), one then generates a flow of prana which strikes syllables for fire and wind underneath the kapala to make its contents boil and in a sense unify. This now ambrosial nectar (amrita) emits the syllables Om, Ah, Hung, dispersing the blessing of pure Buddha body, speech and mind. This simply radiates. It is used to bless torma offerings and nectar used in offerings, or in a more general way tsok offerings as well as the general environment.

Om Ah Hung Ha Ho Hri Hung Hung Phe Phe So Ha.

There is another side to this as well; it seems an importantly powerful thing to keep in mind at some level that the five meats and five nectars were intended to be transgressive repulsive substances. Shocking and caste destroying, they arose directly out of the charnel ground culture that figures so largely in Buddhist Tantra. There is power in our response to disgust, to fear, guilt, lust and all those emotions that lurk around the edges of our movement through the world; we all have our own relationships to purity and impurity, and they are a lot more complicated than we like to assume. Guilt, fear, self-righteousness, abandonment, woe, depression, anger, disgust- an army of emotions- are related to how and why we connect to/react to purity and impurity- we carry these reactions with us wherever we go as we label the things around us as clean and or unclean, desirable and undesirable.

A few years ago I was speaking with the abbot of a Buddhist monastery in India about the historical development of tantric applications of using impure substances. In his reply he said that things are so much more different today in trying to connect with these practices. It’s hard to see rotting corpses, scary wild animals feasting on human remains, lepers, one can’t go down to a charnel ground these days to do a puja around bodies in various states of decay. With the use of toilet paper, some of the stigma of the use of the left hand in India is less powerful, and in western countries there never really was the same kind of stigma in this regard. This he suggested that this is one of the reasons why we use/rely upon visualizations- they can be quite powerful.

However, I wonder where these places of fear are- we all have them- perhaps they are more individualized, or abstracted. Homelessness, illness, mental illness, terrorism, and death, perhaps these are some of the newer “untouchables” of our times. It is important to locate them for ourselves, touch the fear or terror that they bring, and then offer them up- the essence of fear and terror is mind, and mind’s essence is primordially pure. If we can take these sources of impurity and throw them in a pot and cook them with wind and fire, energy and exhaustive passion, they can be seen for what they are, not much different from the purity and wholesomeness that we so easily cling to. What then is the difference? And why to we always run from one towards the other?