Samavati

Samavati was one of the queens of King Udena of Kosambi. Her servant Khujjuttara became a foremost female lay disciple when she sent her to hear the Buddha's teachings and tell her about the teachings. Samavati became so gladdened by Khujjuttara's discourse, she invited Buddha and his monks regularly to the palace to preach the Dharma to her and her 500 ladies in waiting. She became the foremost disciple in loving kindness and compassion.

In the days when India was the fortunate home of an Awakened One, a husband and wife lived within its borders with an only daughter, who was exceedingly beautiful. Their family life was a happy and harmonious one. Then one day pestilence broke out in their hometown. Amongst those fleeing from the disaster area was also this family with their grown-up daughter.

They went to Kosambi, the capital of the kingdom of Vamsa in the valley of the Ganges. The municipality had erected a public eating-hall for the refugees. There the daughter, Samavati, went to obtain food. The first day she took three portions, the second day two portions and on the third day only one portion.

Mitta, the man who was distributing the food, could not resist from asking her somewhat ironically, whether she had finally realized the capacity of her stomach. Samavati replied quite calmly: On the first day her father had died and so she only needed food for two people; on the second day her mother had succumbed to the dreaded disease, and so she only needed food for herself. The official felt ashamed about his sarcastic remark and wholeheartedly begged her forgiveness. A long conversation ensued. When he found out that she was all alone in the world, he proposed to adopt her as his foster-child. She was happy to accept and was now relieved of all worries about her livelihood.

Samavati immediately began helping her foster father with the distribution of the food and the care of the refugees.

Thanks to her efficiency and circumspection, the former chaos became channeled into orderly activity. Nobody tried to get ahead of others any more, nobody quarreled, and everyone was content.

Soon the Finance Minister of the king, Ghosaka, became aware that the public food distribution was taking place without noise and tumult. When he expressed his praise and appreciation to the food-distributor, the official replied modestly that his foster-daughter was mainly responsible for this. In this way Ghosaka met Samavati and was so impressed with her noble bearing, that he decided to adopt her as his own daughter. His manager consented, even if somewhat woefully, because he did not want to be in the way of Samavati's fortune. So Ghosaka took her into his house and thereby she became heiress of a vast fortune and became part of the most exalted circles of the land.

The king, who was living in Kosambi at that time, was Udena. He had two chief consorts. One was Vasuladatta, whom he had married both for political reasons and because she was very beautiful, but these were her only assets. The second one, Magandiya, was not only very beautiful, but also very clever though without heart. So the King was not emotionally contented with his two wives.

One day king Udena met the charming, adopted daughter of his Finance Minister and fell in love with her at first sight. He felt magically attracted by her loving and generous nature. Samavati had exactly what was missing in both his other wives. King Udena sent a messenger to Ghosaka and asked him to give Samavati to him in marriage. Ghosaka was thrown into an emotional upheaval. He loved Samavati above all else, and she had become indispensable to him. She was the delight of his life. On the other hand, he knew his king's temperament and was afraid to deny him his request. But in the end his attachment to Samavati won and he thought: "Better to die than to live without her."

As usual, King Udena lost his temper. In his fury he dismissed Ghosaka from his post as Finance Minister and banned him from his kingdom and did not allow Samavati to accompany him. He took over his minister's property and locked up his magnificent mansion. Samavati was desolate that Ghosaka had to suffer so much on her account and had lost not only her, but also his home and belongings. Out of compassion for her adopted father, to whom she was devoted with great gratitude, she decided to make an end to this dispute by voluntarily becoming the king's wife. She went to the Palace and informed the King of her decision. The king was immediately appeased and restored Ghosaka to his former position, as well as rescinding all other measures against him.

Because Samavati had great love for everyone, she had so much inner strength that this decision was not a difficult one for her. It was not important to her where she lived: whether in the house of the Finance Minister as his favorite daughter, or in the palace as the favorite wife of the king, or in obscurity as when she was in the house of her parents, or as a poor refugee — she always found peace in her own heart and was happy regardless of outer circumstances.

Samavati's life at the court of one of the Maharajas of that time fell into a harmonious pattern. Amongst her servants, there was one, named Khujjuttara the "hunch-backed." Outwardly she was ill-formed, but otherwise very capable. Everyday the Queen gave her eight gold coins to buy flowers for the women's quarters of the palace. But Khujjuttara always bought only four coins worth and used the rest for herself. One day when she was buying flowers again for her mistress from the gardener, a monk was taking his meal there. He was of majestic appearance. When he gave a discourse to the gardener after the meal, Khujjuttara listened. The monk was the Buddha. He directed his discourse in such a way that he spoke directly to Khujjuttara's heart. And his teaching penetrated into her inner being. Just from hearing this one discourse, so well expounded, she attained stream-entry. Without quite knowing what had happened to her, she was a totally changed person. The whole world, which had seemed so obvious and real to her until now, appeared as a dream, apart from reality. The first thing she did that day was to buy flowers for all of the eight coins. She regretted her former dishonesty deeply.

When the Queen asked her why there were suddenly so many flowers Khujjuttara fell at the Queen's feet and confessed her theft. When Samavati forgave her magnanimously, Khujjuttara told her what was closest to her heart, namely, that she had heard a discourse by the Buddha, which had changed her life. She could not be specific about the contents of the teaching, but Samavati could see for herself what a wholesome and healing influence the teaching had had on her servant. She made Khujjuttara her personal attendant and told her to visit the Monastery every day to listen to the Dhamma and then repeat it to her.

Khujjuttara had an outstanding memory and what she had heard once, she could repeat verbatim. Later on she made a collection of discourses she had heard from the Buddha or one of his enlightened disciples during these days at Kosambi, and from it developed the book now called Itivuttaka ("It-was-said-thus"), composed of 112 small discourses.

When king Udena once again told his beloved Samavati that she could wish for anything and he would fulfill it, she wished that the Buddha would come to the palace daily to have his food there and propound his teaching. The king's courier took the message of this perpetual invitation to the Buddha, but he declined and instead sent his cousin Ananda.

From then on Ananda went to the palace daily for his meal and afterward gave a Dhamma discourse. The Queen had already been well prepared by Khujjuttara's reports, and within a short time she understood the meaning and attained to stream-entry, just as her maid-servant had done.

Now, through their common understanding of the Dhamma, the Queen and the maid became equal. Within a short time, the teaching spread through the whole of the women's quarters and there was hardly anyone who did not become a disciple of the Awakened One. Even Samavati's step-father, the Finance Minister Ghosaka, was deeply touched by the teaching. Similarly to Anathapindika, he donated a large monastery in Kosambi to the Sangha, so that the monks would have a secure and satisfying shelter. Every time the Buddha visited Kosambi he stayed in this Monastery named Ghositarama, and other monks and holy people also would find shelter there.

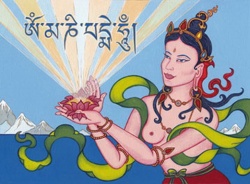

Through the influence of the Dhamma, Samavati became determined to develop her abilities more intensively. Her most important asset was the way she could feel sympathy for all beings and could penetrate everyone with loving-kindness and compassion. She was able to develop this faculty so strongly that the Buddha called her the woman lay-disciple most skilled in metta ("loving-kindness"). (A I.19)

This all-pervading love was soon to be tested severely. It happened like this: The second main consort of the king, Magandiya, was imbued with virulent hatred against everything "Buddhist." Once her father had heard the Buddha preach about unconditional love to all beings, and it had seemed to him that the Buddha was the most worthy one to marry his daughter. In his naive ignorance of the rules of the monks, he offered his daughter to the Buddha as his wife. Magandiya was very beautiful and had been desired by many suitors already.

The Buddha declined the offer but by speaking a single verse about the unattractiveness of the body caused her father and mother to attain the fruit of non-returning. This was the Buddha's verse, as recorded in the Sutta Nipata (v.835):

Having seen craving with Discontent and Lust,[*]

There was not in me any wish for sex;

How then for this, dung-and-urine filled, that

I should not be willing to touch with my foot.

* [The three beautiful daughters of Mara (the tempter).]

But Magandiya thought that the Buddha's rejection of her was an insult and therefore hatred against him and his disciples arose in her. She became the wife of King Udena and when he took a third wife, she could willingly accept that, as it was the custom in her day. But that Samavati had become a disciple of the Buddha and had converted the other women in the palace to his teaching, she could not tolerate. Her hatred against everything connected with the Buddha now turned against Samavati as his representative. She thought up one meanness after another, and her sharp intelligence served only to conjure up new misdeeds.

First she told the King that Samavati was trying to take his life. But the King was well aware of Samavati's great love for all beings, so that he did not even take this accusation seriously, barely listened to it, and forgot it almost immediately.

Secondly, Magandiya ordered one of her maid-servants to spread rumors about the Buddha and his monks in Kosambi, so that Samavati would also be maligned. With this she was more successful. A wave of aversion struck the whole order to such an extent that Ananda suggested to the Buddha that they leave town. The Buddha smiled and said that the purity of the monks would silence all rumors within a week. Hardly had King Udena heard the gossip leveled against the Order, than it had already subsided. Magandiya's second attempt against Samavati had failed.

Some time later Magandiya had eight specially selected chickens sent to the King and suggested that Samavati should kill them and prepare them for a meal. Samavati refused to do this, as she would not kill any living beings. Since the King knew of her all-embracing love, he did not lose his temper, but accepted her decision.

Magandiya then tried for a fourth time to harm Samavati. Just prior to the week which King Udena was to spend with Samavati, Magandiya hid a poisonous snake in Samavati's chambers, but the poison sacs had been removed. When King Udena discovered the snake, all evidence pointed towards Samavati. His passionate fury made him lose all control. He reached for his bow and arrow and aimed at Samavati. But the arrow rebounded from her without doing any harm. His hatred could not influence her loving concern for him, which continued to emanate from her.

When King Udena regained his equilibrium and saw the miracle — that his arrow could not harm Samavati, he was deeply moved. He asked her forgiveness and was even more convinced of her nobility and faithfulness. He became interested in the teaching which had given such strength to his wife.

When a famous monk, named Pindola Bharadvaja stayed at the Ghosita Monastery, the King visited him and discussed the teaching with him. He learned that the young monks, according to the Buddha's advice, instead of having contact with women tried to attain the feelings as towards a mother, sister, or daughter thereby they overcame their dependence on the opposite sex and could live joyously as celibates in spite of their youth. At the end of the discourse, the King was so impressed that he took refuge in the Buddha and became a lay disciple. (S 35,127)

Samavati had been thinking about the wonders of the Dhamma and the intricacies of karmic influences. One thing had led to another: she had come to Kosambi as a poor refugee; then the food-distributor had given her shelter; the Finance Minister had taken her on as his daughter; then she became the King's wife; her maid-servant had brought the teaching to her; and she became a disciple and stream-winner. Subsequently she spread the teaching to all the women in the palace, then to Ghosaka and now lastly also to the King. How convincing Truth was! She often thought in this way and then permeated all beings with loving-kindness, wishing them happiness.

The King now tried more determinedly to control his passionate nature and to subdue greed and hate. His talks with Samavati were very helpful to him in this respect. Slowly this development culminated in his losing all sexual craving when he was in Samavati's company as he was trying to attain the feelings towards women of mother, sister and daughter in himself. While he was not free of sexual desire towards his other wives, he was willing to let Samavati continue on her Path to emancipation unhindered. Soon she attained to the state of once-returner and drew nearer and nearer to non-returner, an attainment which many men and women could achieve in lay-life in those days.

Magandiya had suspended her attacks for some time, but continued to ponder how to harm the Buddha through Samavati. After much brooding, she initiated a plan. She brought some of her relatives to her point of view and uttered slander against Samavati to them. Then she proposed to kill her. So that it would not attract attention, but would appear to be an accident, the whole women's palace was to be set on fire. The plan was worked out in all details. Magandiya left town some time beforehand, so that no suspicion could fall on her.

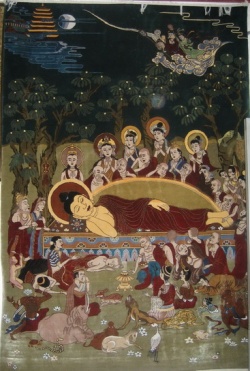

This deed of arson resulted in sky-high flames which demolished the wooden palace totally and the 500 women [*] residing in it were all killed, including Samavati. The news of this disaster spread around town very quickly. No other topic of conversation could be heard there. Several monks, who had not been ordained very long, were also affected by the agitation and after their almsround they went to the Buddha and inquired what would be the future rebirth of these women lay disciples with Samavati as their leader.

* [Five hundred just means 'a great many' in Pali.]

The Awakened One calmed their excited hearts and diverted their curiosity about this most interesting question of rebirth, by answering very briefly: "Amongst these women, O monks, there are some disciples who are stream-enterers, some who are once-returners and some who are non-returners. None of these lay disciples failed to receive the fruits of their past deeds." (Ud VII, 10)

The Buddha mentioned here the first three fruits of the Dhamma: stream-entry, once-returner and non-returner. All these disciples were safe from rebirth below the human realm, and each one was securely going towards the final goal of total liberation. This was the most important aspect of their lives and deaths and the Buddha would not elucidate any further details. Once he mentioned to Ananda that it was a vexation for the Enlightened One to explain the future births of all disciples who died. (D 16 11)

The Buddha later explained to some monks who were discussing how "unjust" it was that these faithful disciples should die such a terrible death, that the women experienced this because of a joint deed they had committed many life-times ago. Once Samavati had been Queen of Benares. She had gone with her ladies-in-waiting to bathe and feeling cold, she asked that a bush be burned to give some warmth. She saw only too late that a monk — a Pacceka Buddha — was sitting immobile within the bush; he was not harmed, however, because one cannot kill Awakened Ones. The women did not know this and feared that they would be blamed for having made a fire without due caution. Thereupon Samavati had the deluded idea to pour oil over this monk who was sitting in total absorption, so that burning him would obliterate their mistake. This plan could not succeed however, but the bad intention and attempt had to carry karmic resultants. In this lifetime the ripening of the result had taken place.

The Buddha has declared that one of the favorable results of the practice of Metta (loving-kindness) is the fact that fire, poison and weapons do no harm to the practitioner. This has to be understood in such a way: during the actual emanation of loving-kindness the one who manifests this radiance cannot be hurt, just as Samavati proved when the king's arrow did not penetrate her.

But at other times fire could incinerate her body. Samavati had become a non-returner, and was therefore free of all sensual desire and hate and no longer identified with her body. Her radiant, soft heart was imbued with the four divine abidings [*] and was unassailable and untouched by the fire. Her inner being could not be burned and that which was burned was the body only. It is a rare happening that one of the Holy Ones is murdered (see Mahamoggallana, Kaludayi) or that one of the Buddhas is threatened with murder (see Devadatta's attempt on the Buddha Gautama) and equally rare is it to find that one perfected in metta and attained to non-returner should die a violent death. All three types of persons, however, have in common that their hearts can no longer be swayed by this violence.

* [Four divine abidings: Loving-kindness, Compassion, Sympathetic Joy, Equanimity.]

Samavati's last words were: "It would not be an easy matter, even with the knowledge of a Buddha, to determine exactly the number of times our bodies have thus been burned with fire as we have passed from birth to birth in the round of existences which has no conceivable beginning. Therefore, be heedful!" Those ladies meditated on painful feeling and so gained the Noble Paths and Fruits.

Two thousand years after the Parinibbana of the Buddha, in 1582, soldiers burned a Buddhist Monastery in Japan and all the monks inside were burned to death. The last thing the soldiers heard before everything burned down were the words of the Abbot:

Who has liberated heart and mind,

For him fire is only a cool wind.

Referring to the tragedy of the fire at Kosambi, the Buddha spoke the following verse to the monks:

The world is in delusion's grip,

Its form is seen as real;

The fool is in the "assets" [*] grip,

Wrapped about with gloom,

Both seem to last forever

But nothing is there for one who Sees.

* [Assets: Upadhi. The basis for life and continued birth and death.]

King Udena was overwhelmed with grief at Samavati's death and kept brooding about who could be the perpetrator of this ghastly deed. He came to the conclusion that it must have been Magandiya. He did not want to question her directly because she would deny it. So he thought of a ruse. He said to his Ministers: "Until now I have always been apprehensive, because Samavati was forever seeking an occasion to slay me. But now I shall be able to sleep in peace." The Ministers asked the king who it could have been that had done this deed, "Only someone who really loves me," the king replied. Magandiya had been standing near and when she heard that, she came forward and proudly admitted that she alone was responsible for the fire and the death of the women and Samavati. The King said that he would grant her and all her relatives a boon for this.

When all the relatives were assembled, the King had them burned publicly and then had the earth plowed under so that all traces of the ashes were destroyed. He had Magandiya executed as a mass-murderess, which was his duty and responsibility, but his fury knew no bounds and he still looked for revenge. He had her killed with utmost cruelty. She died an excruciating death, which was only a fore-taste of the tortures awaiting her in the nether world, after which she would have to roam in samsara [*] for a long, long time to come.

* (Samsara: rounds of existence.]

Soon King Udena regretted his revengeful and cruel deed. Again and again he saw Samavati's face in front of him, full of love for all beings, even for her enemies. He felt he had removed himself from her even further than her death had done, because of his violent fury. He began to control his temper more and more and to follow the Buddha's teachings ardently.

Two women, who had been friends of Samavati, were so moved by this tragedy and saw the impermanence of all earthly things so clearly, that they entered the Order of Nuns. One of them soon became an arahant, fully enlightened, and the other one after twenty-five years of practice. (Thig 37 and 39).

Samavati, however, was reborn in the realm of the Pure Abodes, where she would be able to reach Nibbana. The different results of love and hate could be seen with exemplary clarity in the lives and deaths of these two Queens. When one day the monks were discussing who was alive and who dead, the Buddha said that Magandiya while living, was dead already; while Samavati, though dead, was truly alive, and he spoke these verses:

Heedfulness — the path to the Deathless,

heedlessness — the path to death,

the heedful ones do not die;

the heedless are likened to the dead.

The wise then, recognizing this

as the distinction of heedfulness,

in heedfulness rejoice, delighting

in the realm of Noble Ones.

They meditate persistently,

constantly; they firmly strive

the steadfast to reach Nibbana,

the Unexcelled Secure from bonds.

— Dhp 21-23

The Buddha declared Samavati to be foremost among those female lay disciples who dwell in loving-kindness (metta).

Sources: Dhammapada Commentary to vv. 21-23; Commentary to Anguttara Nikaya Vol. I (on those Foremost); "Path of Purification" p. 417.

Queen Samavati had many maids-of-honour who attended to her every need. Among them was a maid called Khujjuttara whose duty was to buy flowers for Samavati from the florist Sumana everyday. One day, Khujjuttara had the opportunity to listen to a sermon delivered by the Buddha at the home of Sumana. Because of her spiritual attainment in her previous lives, the words of the Enlightened One helped her to attain Sotapatti. On returning to the palace, she repeated the sermon to Samavati and her other maids and they also realised the Dhamma. From that day, Khujjuttara did not have to do any major work, but was looked upon as mother and teacher to Samavati. Being an extremely intelligent person, she listened to the discourses of the Buddha and repeated them to Samavati and her maids. So great was her intellect that in the course of time, Khujjuttara even mastered the Dhamma.

Samavati and her maids liked to see and pay homage to the Buddha; but were afraid that the king might disapprove, so they would look at the Buddha by peeping through openings in the palace walls. They paid respects to the Buddha in this manner every time he passed the palace on his way to the homes of other devotees.

At that time, the king had another consort by the name of Magandiya. She was the daughter of a brahmin. The brahmin once decided that the Buddha was the only person who was worthy enough to marry his very beautiful daughter. So, he offered to give his daughter in marriage to the Buddha. Turning down his offer, the Buddha said, 'Even after seeing the most beautiful girls, Tanha, Arati and Raga, the daughters of Mara, I felt no desire in me for sensual pleasures. After all, what is this body which is full of filth?" The Buddha knew from the beginning that the brahmin and his wife had reached the stage of mental purification where they could attain Anagami that very day, hence his reply to the brahmin in the above manner.

On hearing those words of the Buddha, both the brahmin and his wife realised that all beauty is impermanent, and attained the third stage of Sainthood. They entrusted their daughter to the care of her uncle and both joined the Order. Eventually, they attained Arahanthood. But the story does not end there. The daughter, Magandiya, was very proud and she took the Buddha's words as a personal insult. She became very bitter and vowed to take revenge when the opportunity arose.

Later, her uncle presented Magandiya to King Udena and she became one of his consorts. Magandiya learned of the arrival of the Buddha in Kosambi and how Samavati and her maids paid homage to him through holes in the walls of their living quarters. She planned to take her revenge on the Buddha and to harm Samavati and her maids. Magandiya told the king that Samavati and her maids had made holes in the walls of their living quarters and were being unfaithful to him. King Udena saw the holes in the walls, but when the matter was explained to him he did not get angry.

But Magandiya persisted in trying to make the king believe that Samavati was not loyal to him and was trying to kill him. On one occasion, knowing that the king would be visiting Samavati within the next few days and that he would be taking along his lute with him, Magandiya inserted a snake into the lute and covered the hole with a bunch of flowers. Magandiya followed King Udena to Samavati's quarters after trying to stop him on the pretext that she had some premonition and that she was worried about his safety. At Samavati's place Magandiya removed the bunch of flowers from the hole of the lute. The snake came out hissing and coiled itself on the bed. When the king saw the snake he believed Magandiya's words that Samavati was trying to kill him. The king was furious. He commanded Samavati to stand and all her ladies to line up behind her. Then he fitted his bow with an arrow dipped in poison and shot the arrow. But Samavati and her ladies bore no ill towards the king and through the power of goodwill (metta), the arrow did not hit the target although the king was an excellent archer. Seeing this obvious miracle, the king realised the innocence of Samavati and he gave her permission to invite the Buddha and his disciples to the palace for almsfood and religious discourses.

Magandiya, realising that none of her plots had materialised, made a final, infallible plan. She sent a message to her uncle with full instructions to go to Samavati's palace and burn down the building with all the women inside. As the house was burning, Samavati and her maids-of-honour being advanced in spiritual attainment, continued to meditate in spite of the danger. Thus, some of them attained the second stage of Sainthood and the rest were also benefited before the palace was gutted with them inside.

As soon as he heard the news, the king rushed to the scene, but it was too late. He suspected that it was done at the instigation of Magandiya but he did not show that he was suspicious. Instead, he said, 'While Samavati was alive I had been fearful and alert thinking I might be harmed by her; only now is my mind at peace. Who could have done this? It must only have been done by someone who loves me very dearly.' Hearing this, the foolish Magandiya promptly admitted that it was she who had instructed her uncle to do this terrible deed. Thereupon the king pretended to be very pleased with her and said that he would grant her a great favour, and honour all her relatives. So, the relatives were sent for and they came gladly. On arrival at the palace, all of them, including Magandiya, were seized and put to death in the palace courtyard. Thus the evil Magandiya was punished for plotting the death of the holy queen and her attendants.

When the Buddha was told about these two incidents, he said that those who are mindful do not die; but those who are negligent are as dead even while living.