Vidyaraja

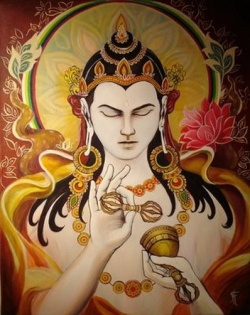

These esoteric deities are the kings of mystic knowledge who represent the power of the Buddhas to vanquish blind craving. They are known as the the kings of mystic knowledge because they wield the mantras, which are the mystical spells made up of Sanskrit syllables imbued with the power to protect practitioners of the Dharma (Buddhist Law) from all harm and evil influences. The Vidyarajas appear in terrifying wrathful forms because they embody the indomitable energy of compassion which breaks down all obstacles to wisdom and liberation.

There are two groups of Vidyarajas that are well known. The most famous is the group of five led by Fudo Myo-o. These five are the emanations of the Buddhas of the four cardinal directions and the center which figure prominently in Esoteric Buddhist practice. There is also a group of eight, which includes Aizen Myo-o, who are emanations of the Bodhisattvas.

The two Vidyarajas who appear on the mandala are Achalanatha and Ragaraja, known in Japanese as Fudo Myo-o and Aizen Myo-o respectively. They are each represented by their respective bijas, "seed syllables" that embody their essence. In this case, the seed syllables are written in Siddham, a variant of Sanskrit. They are the only parts of the mandala written in the form of Sanskrit bijas. According to Jacqueline Stone, Fudo Myo-o and Aizen Myo-o represent, respectively, the doctrines that samsara is nirvana (shoji soku nehan in Japanese) and “the defilements are bodhi“ (bonno soku bodai in Japanese)." The first principle means that nirvana is not another realm but the true reality of the world of birth and death. The second principle means that bodhi, or enlightenment, is not the eradication of the defilements, but their liberation and transmutation into the wholesome energy of the enlightened mind.

Fudo Myo-o and Aizen Myo-o are sometimes identified with the Nio, the Two Deva Kings, who are a dual form of Dainichi Nyorai, who is a personification of the Dharmakaya or universal body of the Buddha. As such, Fudo Myo-o represents the element of spirit or mind, the [[Diamond World Mandala, and subjective wisdom; while Aizen Myo-o represents the five elements of earth, air, fire, water, and space, as well as the Womb World Mandala, and objective truth. Together the pair represent all of the things which are united in the universal life of the Buddha - body and mind, wisdom and truth, and the two mandalas (Ryokai Mandara). The Two Nio Kings are often found guarding the main gates to temple and monasteries as fierce giant warriors.

the Myo-o had his origin in one of the Hindu deities, Siva. Myo-os, with multiple forms were incorporated into the esoteric Buddhist pantheon, while hierarchically placed next to the buddha and bodhisattva, i.e. Myo-os ranked third important position, while fourth rank was given to the devas in the Ten-bu group. Therefore, being originated from one of the Brahmanical (Hindu) deities, the Myo-o or Vidyaraja can be easily considered to be one of the aspects of fusion of Indian culture that occurred in China, Mongolia, Korea and in Japan. The Myo-o deities, after their incorporation into the esoteric Buddhism in the 9th century, gained high popularity in Japan.

The Myo-os or Vidyarajas, kings of light and wisdom, are considered to be the “incarnations of the cosmic Buddha” and the Myo-os gained popularity for the belief that Myo-o or Vidyaraja protects the worshipers with the power of sacred word Vidya which means “Mantra or Dharai: ti”.

Being her supervisor at the Viva-Bharati university for her Ph.D. thesis, I had been fully confident that Sampa Biswas would prove her worth in researches on aspects of cultural relations between our two countries, India and Japan, and like her first publication entitled, Indian Influence on the Art of Japan, her present publication too will be equally acclaimed internationally.

I have no hesitation to say that the present volume is an in-depth study on the interesting roles which the Myo-os play in providing the believers promises of protection from the evil effects of various kinds. Sampa Biswas has dealt with the different iconographic features of the Myo-Os who are variously called Fudo Myo-o (Acalanatha), Aizen Myo-o (Ragaraja), Kongoyasha Myo-o (Vajrayaka), Gundari Myo-o (Kuiua1i), GO Dai Myo-o (Five Wisdom Kings) and also some of the fierceful forms of the deity.

The present research study would surely be an important example of Indo-Japanese cultural relations which started from the sixth century (538 CE).

THE present monograph is meant to bring to the notice of academic circle the historical background of esoteric Buddhism in Japan, the nature of an esoteric Buddhist deity called Fudo Myo-o (Sk. Acalanatha Vidyaraja) which has been enjoying a very wide popularity in Japan for quite an extent of time. The evolution of esoteric Buddhism or Vajrayana Buddhism from Mahayana Buddhism in India, and the spread of Vajrayana Buddhism in Japan from China during the eighth century CE, and the growth and promotion of esoteric culture among the vast masses of people of Japan provide a very interesting scope of study.

Not much endeavour has been made to study in detail the complex nature of Fudo Myo-o, an important esoteric deity and the diverse artistic expressions of Fudo as preserved in sculpture and painting in Japan, showing the images and their iconographic peculiarities.

The present monograph which deals in brief about Vajrayana Buddhism, the historical background of esoteric Buddhism or Vajrayana in Japan, the iconography, nature and characteristics of the god Fudo Myo-o, and the artistic creations of Fudo in Japan from the ninth to the fourteenth century CE, is the outcome of my research work. The purpose of the present work is to present a detailed study about the god Fudo Myo-o and an attempt is made to highlight the rise of esoteric Buddhism in Japan, the philosophy of esoteric Buddhism, the nature, iconography and symbolism of Fudo MyO-O and the representations of the deity in sculpture and painting preserved in Japan and elsewhere. While selecting the subject of the present study, I was mainly attracted by the number of colorful depictions of the god Fudo and its peculiar iconography. I noticed that very limited work has so far been done on this deity and thought that a detailed study on the subject might bring about various facets of the deity, and art associated with it. The method adopted for the study of the subject has been mainly based on Buddhist literature in Sanskrit, previous scholarly works by eminent writers on the subject published in books, journals, and a detailed study of the specimens of art found in different books. Esoteric Buddhism, called Mikky in Japan, was part of a widespread movement, which had been powerful in India in the sixth and seventh centuries c and was transmitted to China by Buddhist monks, where it quickly established itself. Specialists of esoteric Buddhism who propagated the sect to China were ubhakarasithha (CE 637-741) from Nalanda, who translated about 30 Sutras and treatises at Chang’an including the Mahavairocana Sutra, the fundamental scripture of esoteric Buddhism; Vajrabodhi (CE 671-741) from Nalanda, who translated about 20 texts of esoteric Buddhism, and Amoghavajra (cE 705-55) who met Vajrabodhi in Java in CE 717 and became his disciple. He brought about 100 Sanskrit texts including the Tatt va-S ath graha, the highest authority of esoteric Buddhism. Amoghavajra had Hui-Kyo, a Chinese, among his disciples. Kobo Daishi (or popularly known as Kukai) from Japan visited China when Hui-KyO was in his last days, and became his disciple and learnt esoteric Buddhism rapidly.

The new teaching was brought to Japan in c 806 by Kukai, and was known as Shingon, or True Word (5k. Mantrayana). The core of Shingon Buddhism is the belief in the essential identity of all things in the person of the Supreme Buddha, Mahavairocana in Sanskrit, or Dainichi Nyorai in Japanese. To the Shingon believer, there is no difference between the world of senses and the world of ultimate reality, for both are manifestations of the same cosmic principle. There is no difference between the image and the deity, for in Shingon, the images are merely representations of the various aspects of Dainichi. The power and the wonder of mantra lay in its realization by meditation through the maijilala, and its appropriate conceptualization as ultimate meaning.

The new spiritual energy found expression in gigantic paintings of the two cosmograms or maiyçlalas of Garbhadhatu and Vajradhatu. They co-ordinated the esoteric traditions of the ancient Indian universities of Nalanda in the north and Kanci in the south.

Radical change was noticed in the deities themselves. Their strangeness and exoticness clearly revealed their Indian influence. Most of the images were not shown to the public but were kept hidden in the inner sanctum of the temples. Mikkyu images were often given an uncanny, wild aspect with multiple limbs and ferocious expressions. Such tendencies had already appeared at the end of the Nara period (CE 710-897) as in the many-armed Fukukensaku Kannon (Sk. Bodhisattva Amoghapasha) at the sangatsudo of Todai-ji, but these images can be regarded as forerunners of what was to come.

In addition to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas, there were many new gods, among them the Five Great Kings, or Go-Dai-Myo-o, who as manifestations of Dainichi’s wrath against evil, have fierce and terrifying forms. The most important of the MyO-O, one of the main deities of Shingon sect, is Fudo Myo-o, originally a form of the Hindu God iva. Usually appearing in the midst of the four other MyO-Os or Radiant Kings, are Daiitoku (Sk. Mahatejas), known in Tibetan Tantric pantheon as Yamantaka, Gosanze (Sk. Trailokyavijaya), Gundari (5k. Kundali), and Kongoyasha (5k. Vajrayaka). These MyO-O images were rather grotesque with their projecting fangs and childlike bodies adorned with skulls and snakes.

Fudo Myo-o is often represented singly both in painting and sculptures, as a terrifying god with facial expression full of wrath, attended by Kongara Doji and Seitaka or Cefaka Doji. As the Immovable One, he stands on a symbolic rock surrounded by flames, holding a rope and a sword with which he conquers all evils. Variations come in the number of attendants usually a pair of youths, but occasionally six or even eight. The portrayal of this god is done in various colours, yellow, blue or red.

The benevolent Fudo Myo-o is discussed in the Acala Sutra, Mahavairocana Sutra, Sadhanamaia and Nispannayogavali, but the earliest pictorial representation of him is found in the Taizo-kai (5k. Garbhadhatu Mandala). During the entire Heian period (CE 897-1185), the artistic gifts of the Japanese people were channelled primarily into religious symbolism, and within the narrow restrictions of traditional Buddhist iconography, a surprising range of emotional expressions was possible. The highest levels of artistic insight were imbued with spiritual exaltation such as that experienced by great monks like Ktikai, Saicho, Sbinkai, etc

This interesting subject has been dealt with considerable care and objectivity bearing out in great depth the evolution of Vajrayana Buddhism in India, its spread in China and Japan, the study of esoteric Buddhist art, iconography, nature and visualization of Fudo Myo-o in art.

The monograph is divided into five chapters, besides the Preface and Introduction. The first chapter gives an account of the introduction of Buddhism in Japan in the year CE 538, and the gradual transformation into esoteric doctrines during the ninth century. The predominance of faith in Mahavairocana and popularity in the worship of Fudo Mybô, the conqueror of all disasters and evil, have been discussed.

In the second chapter, the description of Fudo Myo-o as found in Buddhist literary sources from India, the iconography of Fud O, his attendants, Fudo’s symbolic instruments, and interpretation of mudras (hand gestures), postures, emblems carried by Fudo have been studied.

The third and fourth chapters deal with the visual representation of FudO MyO-o in painting and sculpture. The Bibliography, Glossary and Historical Chronology of Japan have also been added at the end. The written work has been amply supported by photographs of sculpture and paintings of Fudo. The following books have been consulted and used to obtain illustrated material: Art in Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, Heibonsha John Weatherhill, New York, Tokyo, 1972; National Treasures of Japan Series II, IV, V. Mission for Protection of Cultural Properties, 1952, 1956, 1959; Miyahara Ryusen, Buddhist Painting, Kosei Publishing House, Tokyo, 1981; Danielle Elisseeff and Vadim, Art of Japan, Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York, 1980; Masao Ishida, Japanese Buddhist Prints, Kodansha mt. Ltd. and Shibundo, Tokyo, Palo Alto, New York, San Francisco, 1987; Masao Ishida, Japanese Buddhist Prints, Kodansha Tnt. Ltd. and Shibundo, Tokyo, Palo Alto, New York, San Francisco, 1987; Hisaki Mori, Sculptures of Kamakura Period, Heibonsha/John Weatherhill, New York, Tokyo, 1974; Hisatoya Ishida, Esoteric Buddhist Painting, Kodansha International Ltd. and Shibundo, Tokyo, New York, San Francisco, 1987; Edward J. Kidder, Art of Japan, Thames and Hudson, London, 1985; Awakawa Yasuichi, Zen Painting, Kodansha International Ltd., 1970 Victor Harris and Ken Matsushima, Kamakura: The Renaissance of Japanese Sculpture 1185-1333, British Museum Press, 1991, and Takaaki Sawa, Art in Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, Weatherhill/Heibonsha, Tokyo, New York.

I take this opportirity to express my deep sense of gratitude to Dr D.N. Bakshi Director, Japanese Study Centre, Kolkata, for writing the Foreword of the book. I am also thankful to the authorities of the libraries of Japan Foundation, New Delhi, National Museum Institute, National Museum, and Kala Nidhi, Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, for their co-operation and help.