Rational Buddhism

The purpose of this blog is to explore how far Buddhism can be supported by rational arguments, both from the philosophical point of view, and also in terms of the observed effects of Buddhist practices.

In other words, if we regard Buddhism as a combination of a philosophy, psychology and religion, then how much mileage can we get from the first two aspects before we have to start invoking religious faith? This is not to say that the religious aspect should be abandoned or disparaged in any way, and I am certainly not advocating the mechanistic reductionism known as 'Secular Buddhism'.

The advantage of pursuing the philosophical and psychological approaches is that of maintaining a common basis for discussion with science, medicine and Western philosophy for as far as possible, until the paths diverge.

Buddha told us to analyse his teachings.

Of course most religions don't like having their basic tenets subjected to searching analysis, and one cult has abandoned reason altogether, to the extent that you're likely to get your head chopped off for being too rational.

But Buddhism is different. In the Kalama Sutra, Buddha said that all religious teachings, including his own should...

(1) Not be believed on the basis of religious authority, or 'holy' books, or family/tribal tradition, or even coercion and intimidation by the mob.

BUT INSTEAD ONE SHOULD

(2) Test the methodology by personal experience. Does it do what it says on the box?

(3) Is the philosophy rational? Or does it require you to believe six impossible things before breakfast?

(4) Judge the tree by its fruits. Is it beneficial, or does it tell you to act against your conscience and 'The Golden Rule'.

According to Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, Buddha told his disciples time and time again not to accept his teachings out of blind faith, but to test them as thoroughly as they would assay gold. It is only on the basis of valid reasons and personal experience that we should accept the teachings of anyone, including Buddha himself.

The advantages of rationalism

One advantage of establishing a rational basis for Buddhism is that it gives Buddhism an 'intellectual respectability' at a time when the intellectual prestige of other religions is in steep decline, due to increasing obscurantism, which takes variety of forms varying from creationist anti-science to outright terrorism.

This 'intellectual respectability' also may help to prevent Buddhism being hit by collateral damage from increasing prejudice against all religions resulting from jihadist aggression.

Reason versus Revelation

Most religions contain some 'revealed doctrines' or 'dogmas', which were revealed long ago to one person or a few people, and then not to any others.

In all religions other than Buddhism, these ancient, unprovable, unrepeatable revelations are fundamental articles of faith on which the rest of the belief-system is constructed.

In contrast, Buddhism's fundamental doctrines are accessible to reason and investigation in terms of shared, repeatable experience.

The Four Foundations of Buddhism

There are many different schools of Buddhism, but all are built upon the foundations of the Four Seals of Dharma. These Four Seals can be derived from rational analysis.

The four seals are

(i) Lack of inherent existence

(ii) Impermanence

(iii) Unsatisfactoriness

(iv) Liberation of the mind

The most fundamental of these seals is the first, Lack of Inherent Existence, from which the other three follow logically*.

First Seal - Lack of inherent existence (emptiness)

No phenomenon is a ‘thing in itself’. The more you look for it, the less you find it. Things disappear under analysis. A car exists as a conventional truth, convenient for our everyday lives - a kind of working approximation. But on dissection, logical analysis can find no ‘essential’ car, just a heap of parts that at a certain arbitrary stage of assembly is designated ‘car’, and at a certain arbitrary stage of disassembly is designated 'pile of junk'.

Outside our mind there is no defining ‘carness’ . Similarly, if you gradually decrease the height of the sides of a box until it becomes a tray, there is no point at which 'boxiness' leaves and 'trayfullness' jumps into the structure, with the box being automatically transformed into a tray. It’s all arbitrary mental designation. This arbitrariness is the ultimate truth of how things exist to our minds. And it goes all the way down to the fundamental particles of matter.

So how do things exist?

According to Buddhist philosophy, all functioning phenomena are dependently related to other phenomena and their existence arises from three relationships:

(a) Causality: Phenomena exist dependent upon causes and conditions.

(b) Structure: Phenomena depend upon the relationship of whole to parts.

(c) Most profoundly, phenomena depend upon imputation, attribution, or designation by the mind. It's the mind that designates what's a tray and what's a box.

More on Lack of Inherent Existence:

Sunyata

Inherent existence

Reification

Existence and Impermanence

Ideal forms and essentialism

Partless particles

Second Seal - Impermanence

The impermanence of all functioning phenomena is an inevitable logical consequence of their emptiness of inherent existence.

No functioning phenomenon can be static, because to function it must change and be changed, it must give something of itself or receive something into itself. A truly unchanging phenomenon would reside in splendid isolation and could never even be known to exist. All functioning phenomena are composite and impermanent. What we term ‘existence’ is really just impermanence in slow-motion.

From Impermanence, Interdependence & Emptiness

“The ideas of impermanence, interdependence and emptiness are central to Buddhist teaching - and to the whole Buddhist worldview actually.

What these ideas boil down to really is that there is no permanent essence to anything. No part of anything lasts forever or is eternal. Everything (and everyone) that exists does so because of the interrelatedness of various parts - not because it has a permanent essence or "soul" around which all the parts are organized..."

This is true of all things and all people. All things exist interdependently - not as permanent essences. Thus, all things are ultimately "empty" - which is the Buddhist teaching of emptiness.

Because things are empty, they are impermanent. We forget this, says the Buddha, and act as if things are permanent. We desire them to be permanent and when they turn out not to be, we suffer. We suffer especially when we desire permanent happiness from impermanent things or people. It is not possible for impermanent things or people to provide permanent happiness because they themselves are not permanent..."

More on Impermanence:

Process Philosophy

Existence and impermanence

Subtle impermanence, the quantum vacuum, radioactive decay and causality

Third Seal - The Unsatisfactoriness of Material Existence

All emotions based on the three mental poisons of attachment, aversion and ignorance are ultimately painful. You can never have enough worldly possessions, and even if you did you'd worry about losing them since - as stated in the paragraph above - they are all impermanent. And you've got to lose the lot eventually when you die.

This sense of unsatisfactoriness can range from the severe physical and mental sufferings of people being bombed, burned and raped in war-zones, to the feeling of humiliation suffered by a billionaire who discovers that his business rival has a slightly larger and more luxurious yacht. An object that appeared to be a source of pride and happiness when he bought it, has now turned into a source of shame and aversion.

All materialistic cravings eventually and inevitably lead to disappointment and worse. They cannot provide any ultimate satisfaction. See Dukkha, Dawkins, Darwinism and the Selfish Gene and Symbiotic Mind.

Fourth Seal - The Ultimate Liberation of the Mind

The first three seals of dharma analysed the factors that imprison our minds in a ceaseless and futile process of chasing after the mirages of impermanent phenomena, in the hope of achieving ultimate satisfaction. The fourth seal provides an escape route from this labyrinth of confusion.

The method for liberating the mind from its delusions consists of meditational techniques. These techniques have been empirically tested and shown to provide psychological benefits in the here and now, though of course Buddhists would also claim that they provide benefits in the hereafter (of which more later).

So as far as clinical assessment is concerned, Buddhist meditation does do what it says on the box. As Ed Halliwell writes:

"It is not long since just mentioning meditation tagged you as a gullible new-ager or self-indulgent hippie. Buddhism, if considered at all, had a reputation for promoting withdrawal from this pain-filled world. But in the space of a few short years, core dharma has permeated western society's most influential institutions.

Madeleine Bunting charts the cracks in our once-cherished concepts of individual identity, and notes how the Buddhist teaching of egolessness resonates with corresponding insights from neuroscience and evolutionary psychology. Ideas that chime with Buddhism are being championed by the Royal Society of Arts and the New Economics Foundation, and reported in mainstream media. Before cif belief, I never dreamed I would synchronise my journalistic career and meditation practice, finding national newspaper space to write from a Buddhist perspective.

Buddhism is reaching beyond academia, think tanks and the media. Most GPs are aware of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and cognitive therapy (MBCT), well-researched approaches to health problems which feature meditation as their core component. MBCT is endorsed by the National Institute For Clinical Excellence, and thousands of people are being referred to mindfulness training on the NHS. In Scotland, the government has funded more than 200 healthcare professionals to teach MBCT."

So does acceptance of the Four Seals of Dharma make you a Buddhist?

"Anyone who accepts these four seals, even independently of Buddha’s teachings, even never having heard the name Shakyamuni Buddha, can be considered to be on the same path as he." - Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche

-

However, 'the path' in Buddhism is considered to extend beyond the present lifetime, which brings us on to the next topic - the nature of the mind. According to Buddhist philosophy, the mind is non-physical and formless. The mind 'knows' its object, in the sense of designating meaning to it.

The mind survives the physical death of the body. It is a fundamental aspect of reality that cannot be reduced to physical or biological structures, and is not dependent upon them

The fourth seal of dharma aims to clarify the mind from delusions on a permanent basis, from this life onwards.

Buddhist philosophy rejects materialist explanations for the mind.

Materialism is the belief that all phenomena in the universe, in particular the human mind, are explainable in terms of matter.

In other words, such mental experiences as beauty, love, spirituality, pleasure and pain are reducible to nothing but physical and chemical interactions. According to the materialist view, the mind does not actually exist, but is an emergent property or epiphenomenon of matter.

Although there are not many people who enthusiastically promote the materialist worldview, it has become the default belief of many scientifically educated people that all phenomena are reducible to the activities of matter.

- The Malaise of Materialism

Materialism leads to a rejection of spirituality, both in terms of declining religious belief, and also in the arts where the cult of ugliness, with its obsessions with the sordid and brutalistic, seeks to reduce humans to biological automata.

Of course all religions reject materialism as an article of faith, but none apart from Buddhism attempts to provide any rational philosophical refutation of the materialist worldview.

- Buddhism offers the only coherent critique of materialism

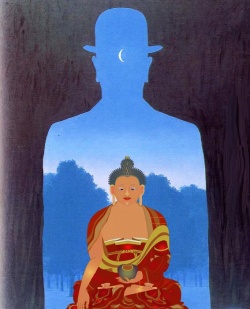

Whitehead said "Christianity ... has always been a religion seeking a metaphysic, in contrast to Buddhism which is a metaphysic generating a religion." In other words, Christianity does not have the metaphysical foundation needed to withstand materialism.

So nowadays it's left to Buddhism to defend the spiritual aspect of humanity from mechanistic materialism, and show that not everything about the human mind can be explained in mechanistic terms.

The Buddhist argument against materialism is to demonstrate that mind is an aspect of reality that is not reducible to material causes and structures.

Note that in Buddhist metaphysics, mind is not a kind of 'thing' or 'substance' because 'things' and 'substances' are dependent upon structure for their existence. The mind can apprehend structure, but does not itself have any vestige of structure, nor can it be reduced to structure (mind is said to be 'formless').

So how does the materialist worldview map on to the Buddhist worldview, and what are the discrepancies?

- Materialism, physicalism and computationalism.

In discussing the differences between Buddhist metaphysics and materialism, we need a more precise definition of the materialist philosophical position, which introduces two rather more modern terms - physicalism and computationalism.

Physicalism is a more precise formulation of the rather vague term 'materialism'. It states that all phenomena, including the mind, are reducible to the laws of physics.

Computationalism is physicalism specifically applied to explaining the function of the human mind. Since all physical systems can be modelled, simulated and explained in terms of datastructures and algorithms, (see Church-Turing Thesis), it follows that if physicalism is true, then the human mind can be modelled, simulated and explained by a computer. This is a more precise statement than the traditional materialist view that the mind is a machine.

Buddhism versus Computationalism

The difference between the Buddhist and the Computationalist view of reality can be stated quite simply:

The Buddhist believes that all functioning phenomena are dependent upon

- Causality

- Structure

- Designation by mind

The Computationalist believes that all functioning phenomena are dependent upon

- Causality

- Structure

...with the mind being reducible to the operations of causality on structure in the same way that the activities of a computer are reducible to the operation of algorithms on datastructures.

To the Buddhist, in contrast, the mind is an irreducible foundation of reality.

Arguments against computationalism.

If computationalism is false, then it seems very likely that mind must be an axiomatic aspect of reality, which is not dependent upon the mechanism of the brain or body, and so may continue to exist after death.

See here for arguments against materialism in general, and here for arguments against the computational theory of mind.

Metarationality versus irrationality in religion

Metarationality deals with valid phenomena which lie beyond the limits of discursive thought. Qualia are prime examples, and much meditational practice deals with the deliberate invocation of qualia.

Also, some types of meditation deliberately seek to go beyond conceptual thought in order to reach nonconceptual awareness.

Other metarational phenomena are those paradoxes that lie at, or just beyond, the limits of logical thought, and which have been investigated by Buddhist philosophers such a Nagarjuna.

According to Hume, the entire field of ethics may be metarational, since reasoned and logical arguments are incapable of going from an 'is' to an 'ought'. Ethics cannot be rationally derived either from knowledge based on logic and definitions, or from observation.

The difference between metarationality and irrationality, is that with metarationality you attempt to explore the landscape beyond the end of the tracks of logical thought, whereas with irrationality you come off the rails long before you reach the end of the line.

Buddhist philosophy is rational until it reaches the limits of logic, wherupon it goes metarational, whereas some religions are just plain irrational from the very start of the journey.

For rationalists such as Richard Dawkins, 'Faith' is very much an F-word .

Faith makes a virtue out of believing unprovable and often improbable propositions. Dawkins contrasts this with the scientific method, which he describes as a system whereby working assumptions may be falsified by recourse to reason and evidence.

The Place of Faith in Buddhism

So is 'Faith' in Buddhism the same kind of unquestioning belief in bizarre and often mutually contradictory assertions as found in other religions, or is it more in the nature of 'Trust'.

Buddha, in his rejection of essentialism and affirmation of the importance of impermanence, displayed an insight into the way that things exist that has only recently been confirmed by science. Buddhist meditational techniques have also recently been empirically verified to have measurable beneficial effects. But how far should we trust Buddhist doctrine when it deals with topics that are metarational?

Trusting the Guide to the Path

Consider the situation where we are hiking on a mountain in the Scottish Highlands.

We are following a map, when suddenly a fog closes in and we can only see a few feet ahead. We decide to get off the mountain as quickly as possible and wait for better weather. The map shows a quick way down which appears to be shorter than the route we took to get here. But do we trust the map?

Well, there are good maps and not so good maps. There are maps originating from the observations of competent mountaineers using suitable equipment and accurate record keeping, and there are maps originating on the back of beer mats drawn from hazy memories in Highland bars at 11 o'clock at night after traversing the malt whisky shelf.

So how do we decide whether to follow the route on the map? How do we know it won't lead us over a cliff or into a bog? Are we prepared to stake our safety and maybe our life on this map?

One way to weigh the risks would be to judge the reliability of the map by what it has shown so far. Has it accurately described the route we've taken?

Or has it shown things that aren't there, and missed out major features that are?

If Buddha's map to the path has proved accurate up to where we are now, then maybe we should have sufficient faith in it to take us a bit further along the path.

TIP - If some aspects of Buddhist beliefs seem unfamiliar, obscure, or confusing, then bear in mind that Buddhism is a process philosophy. Difficult aspects of Buddhism often become much clearer when viewed from a process perspective.