Role of Women in Buddhism

Role of Women in Buddhism

There is no point claiming that the female form has not been the focus of prejudice and subjugation in a majority of times and places. However this is not the invariable state of affairs in Buddhism.

Prajapati, Buddha's step-mother/aunt, walked over a hundred miles to request permission -- even, insist -- on the right of women to become monastics. After she was ordained, she attained the Awakened state and Nirvana along with many of the nuns.

According to accounts by Chinese pilgrims, Faxian and Xuan-zang, when crowds of people gathered at Shankashya eagerly awaiting the Buddha's descent from the Trayastrimsha Heaven (where he had gone to see his deceased mother,) a nun called Utpali vowed to be the first one to greet him. But what chance had a simple nun to compete with powerful heads-of-state amidst their entourages that were there at the foot of the threefold stairway?

Yet because of her earnest devotion, she was transformed into an emperor (or universal monarch) with his full panoply including the Seven Treasures, and so all made way so that she was able to accomplish her vow. First to greet the Buddha, she immediately reverted to her original appearance. In recognition of Utpali's devotion, the Buddha announced her future enlightenment.

The first women of Buddhism by Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D.

Should menstruation prevent women from participating in certain practices? The 13th-century Japanese Buddhist master Nichiren was asked that question and responded in a way that is characteristic of Buddhist teachers of today.

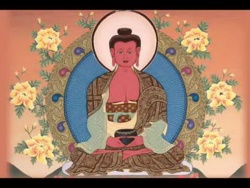

Padmasambhava, the eighth-century Second Buddha, said, "Male, or female there is no great difference. But when the aspiration for enlightenment is developed, the woman is superior." All of his consorts achieved the highest attainment, and Tibetan queen Yeshe Tsogyal was his chief disciple and lineage-holder.

Naropa's "sister" Niguma, and the dakini Sukhasiddhi, are both founders of the Shangpa Kagyu line. Also, without the compassionate intercession of Dagmema, Marpa's wife, who mentored Milarepa, the Kagyu and many other Buddhist lineages might not even exist today.

And there are several others: One famous terton or treasure-revealer was Tibetan stock-woman, Jomo Memmo. Machig Labdron was Padampa Sangye's disciple and the founder of her own Chod and longevity lineages.

The daughter of Terdak Lingpa, founder of Mindroling Monastery near Lhasa and the fifth Dalai Lama's teacher, was the one to transmit the Mindroling lineage.

A-yu Khandro, is only one of numerous other "Women of Wisdom." In 1953, aged 114 years, she attained the Rainbow Body in her hermitage in East Tibet.

Dzogchen master Chatral Rinpoche claims the Drikung Khandro as one of his root gurus. Jetsun Kushok Chimey Luding is a contemporary Sakya master in Vancouver who gave her first empowerment at the age of 18. There are notable women in prominent roles in other denominations, too.

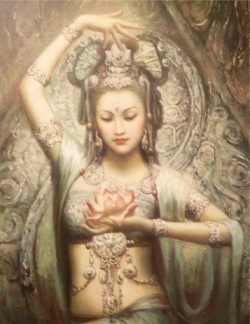

Female deities abound in Tibetan Buddhism. The matriarch of the Drigung Kagyu lineage is grandmother, Achi Chokyi Drolma.

See also, Deities in Female Form

One of the fundamental Vajrayana vows is not to denigrate women. In fact, it is the ultimate or final of the 14 vows that acts as a seal for the others. Tibetan Buddhists refer to sentient beings "numerous as space" as our "mothers."

Also, teachers have said that women practitioners have an advantage in that they are less likely to be wholly goal-oriented, to practice with a view to compete, or to force themselves, and this, coupled with an inclination towards openness, enables their progress.

Nevertheless, in Buddhist monasticism as in some other traditions, there is also a training that treats the body, especially that of a woman, as something particularly revolting.

Peak inside Liz Wilson's Charming Cadavers (U. of Chicago, 1996.)

Female Tertons or Treasure-Finders

The "revelation," or terton, tradition in Himalayan Buddhism is traced to the close disciples of Guru Rinpoche, who only numbered about about 30. Women (a number of them his consorts) comprised a relatively small proportion and tradition says they frequently took rebirth in male form. For example, the terton Longchenpa was acknowledged as Pema Ledreltsal, daughter of King Trisong Deutsen.

One notable early 20th-century woman terton was the Sera Khandro, who figured in the lives of many notable lamas. According to Tulku Thondup (in a short biography of the Chatral Rinpoche, who was a student of hers) she was named Devi Dorje, and became the consort of Pema Dudul Sangngak Lingpa, son of the great terton Dudjom Lingpa, himself a renowned terton. Therefore she was the repository of a number of gTer lineages. Thondup says that she reincarnated as Saraswati, one of his daughters.

The late Chagdud Tulku, foremost disciple of Dudjom Rinpoche, was also in position to hold the spiritual heritage of the Sera Khandro.

Odzer tells us (Kagyu email list:)

I have a few hairs of hers that Yangthang Tulku gave me, they are very precious. I gave one to a friend who put it in her amulet box, and she swears it grew longer when she looked at it again later. Whenever I mention these sacred hairs to a Lama, they usually ask for one!

The role of women in Buddhism

June Campbell in Tricycle, Winter 1996, "Emperor's Tantric Robes"

Karen C Lang's review of Passionate Enlightenment (1994) by Miranda Shaw.

See Female Deities on this site.

See also, Dakini as Shakti for a view of the active role of female deities.

Enlightened Courtesans

In contemporary times and circumstances, prostitutes are not regarded much more differently in China, Tibet and India than from the West. However, that has not always been the case.

Gampopa, commenting on the generosity of mothers -- for all beings are considered to have been our own mother at one time or another -- notes that when she could not afford food for her children, a mother might even prostitute herself for their sakes.

A few of the masters of the Supreme Source, an important Tibetan Dzogchen work, were prostitutes. For example, the father of the prostitute Metsongma Parani was a shudra named Bhahuta, and her mother was Gaden Dhari.

Endowed with wisdom and keen intelligence, fully qualified for the Great Vehicle, she asked Nodjyinmo Changchubma for the essence of the teachings . . . . Then Metsongma Parani perfectly understood the meaning of the primordial state and expressed her realization thus:

I am the prostitute Parani.

As mind is neither male nor female,

When one understands bodhicitta, the supreme view,

Sexual union does not disturb its nature.

As mind is beyond birth and death, even if you kill it, it does not die.

As all of existence is nectar, from the beginning there is no place

for purity and impurity!

And

The prostitute Metsongma Dagnyidma, intuiting that all the phenomena of existence abide in the deep womb of the Mother, aspired after the essential meaning, so she asked Rishe Bhashita for the essence of the teachings . . . . Then Dagnyidma perfectly understood the meaning of the primordial state and expressed her realization thus:

I am the prostitute Dagnyidma!

The sky of the five elements, consorts of the five Tathagatas,

Is itself the dimension of Samantabhadri,

The universal ground is Samantabhadri.

Understanding it, one discovers it is inseparable from space.

Bodhicitta is like the sun rising in space:

Understanding the nature of mind is the best meditation!"

The Supreme Source: The Fundamental Tantra of the Dzogchen Semde by Kunjed Gyalpo, commentary Chogyal Namkai Norbu, tr. Adriano Clemente. Snow Lion, 1999. (38 & 42).

The Changing Status of Women (and also, the Plight of Western Monastics)

Tenzin Palmo (Diane Perry) is an Englishwoman who began studying Buddhism in the 1960's. In 1976, she began a twelve-year meditation retreat in a cave in Ladakh. In the biography, Cave in the Snow by Vicki Mackenzie, she relates how the negative aspects of the role of women in the male-dominated tradition that is Buddhism were brought to light at the first Conference on Western Buddhism. In March 1993, in Dharmasala, seat of the Dalai Lama in exile, she was one of the participating nuns, when:

"An attractive German laywoman, Sylvia Wetzel, took the floor. With a small but discernible gulp she invited His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the assembled throng of luminaries to join her in visualization. 'Please imagine that you are a male coming to a Buddhist center. You see the painting of this beautiful Tara surrounded by sixteen female arhats and you have the possibility to see too Her Holiness the fourteenth Dalai Lama who, in all of her fourteen incarnations, has always chosen a female rebirth,' she began.

'You are surrounded by very high female rinpoches -- beautiful, strong, educated women. Then you see the Bhikshunis coming in, self-confident, outspoken. Then you see the monks coming in behind them -- very shy and timid. You hear about the lineage of lamas of the tradition, who are all female, down to the female Tara in the painting.'

'Remember you are male,' she reminded them, 'and you approach a lama, feeling a little bit insecure and a little bit irritated, and ask "Why are there all these female symbols, female Buddhas?" And she replies, "Don't worry. Men and women are equal. Well, almost. We do have some scriptures which say that a male rebirth is inferior, but isn't this the case? Men do have a more difficult time when all the leaders, spiritually, philosophically and politically are women."

'And then the male student, who is very sincere, goes to another lama, a Mahayanist from the Higher Vehicle School, and says, "I am a man, how can I identify with all these female icons?" And she replies, "You just meditate on Shunyata (Emptiness). In Shunyata no man, no woman, no body, nothing. No problem!"

'So you go to a tantric teacher and say, "All these women and I am a man. I don't know how to relate." And she says, "How wonderful you are, beautiful Daka, you are so useful to us practitioners helping us to raise our kundalini energy. How blessed you are to be a male, to benefit female practitioners on their path to enlightenment."

It was outrageous but delivered in such a charming way that everyone, including the Dalai Lama, laughed. 'Now you have given me another angle on the matter,' he said. In effect Sylvia Wetzel had voiced what millions of women down the centuries had felt. In spite of the mirth, the dam holding back more than 2,500 years of spiritual sexism and pent-up female resentment was beginning to burst.

Others began to join in. A leading Buddhist teacher and author, American nun Thubten Chodron, told how the subtle prejudice she had met within institutions had undermined her confidence to the point that it was a serious hindrance on the path. 'Even if our pain was acknowledged it would make us feel better,' she declared.

Sympathetic male teachers spoke up. 'This is a wonderful challenge for the male -- to see it and accept it,' said a Zen master.

American Tibetan Buddhist monk Thubten Pende gave his views: "When I translated the texts concerning the ordination ceremony I got such a shock. It said that even the most senior nun had to sit behind the most novice monk because, although her ordination was superior, the basis of that ordination, her body, was inferior. I thought, "There it is." I'd heard about this belief but I'd never found evidence of it. I had to recite this text at the ceremony. I was embarrassed to say it and ashamed of the institution I was representing. I wondered, "Why doesn't she get up and leave?" I would.'

The English Theravadan monk Ven Ahjan Amaso also spoke up: 'Seeing the nuns not receiving the respect given to the monks is very painful. It is like having a spear in your heart,' he said.

Then it was Tendzin Palmo's turn, and with all her natural eloquence she told her tale: "When I first came to India I lived in a monastery with 100 monks. I was the only nun,' she said, and paused for several seconds for her words to sink in. 'I think that is why I eventually went to live by myself in a cave.'

Everyone got the point. 'The monks were kind, and I had no problems of sexual harassment or troubles of that sort, but of course I was unfortunately within a female form. They actually told me they prayed that in my next life I would have the good fortune to be reborn as a male so that I could join in all the monastery's activities. In the meantime, they said, they didn't hold it too much against me that I had this inferior rebirth in the female form. It wasn't too much my fault.'

Seizing her chance, she went on to fire her biggest salvo. An expose on the situation of the Western Sangha, particularly the nuns whom she had befriended in Italy. 'The lamas ordain people and then they are thrown out into the world with no training, preparation, encouragement, support or guidance-and they're expected to keep their vows, do their practice and run dharma centers.

This is very hard and I'm surprised that so many of the Western Monastics stay as long as they do. I'm not surprised when they disrobe. They start with so much enthusiasm, with so much pure faith and devotion and gradually their inspiration decreases. They get discouraged and disillusioned and there is no one who helps them. This is true, Your Holiness. It's a very hard situation and it has never happened in the history of Buddhism before.

'In the past the Sangha was firmly established, nurtured and cared for. In the West this is not happening. I truly don't know why. There are a few monasteries, mostly in the Theravada tradition, which are doing well, but for the nuns what is there? There is hardly anything quite frankly. But to end on a higher note, I pray that this life of purity and renunciation which is so rare and precious in the world, that this jewel of the Sangha may not be thrown down into the mud of our indifference and contempt.'

It was an impassioned, formidable cry from the heart.

When she had finished a great hush fell over the gathering. No one was laughing now. As for Tenzin Gyatso, (the Dalai Lama), the Great Ocean of Wisdom, regarded by his people as an emanation of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion, he was sitting there, head in his hands, silently weeping. After several minutes he looked up, wiped his eyes and said softly, 'You are quite brave.' Later the senior lamas commented that such directness was indeed rare and that in this respect the conference had been like a family gathering where everyone spoke their mind frankly."