Sangri-La and Spiritual Powers

This post is the following part of a previous one, continuation of a conversation with a couple I met at Yuksom…

“What about you?, are you also a doctor?,” I asked to the American guy.

“No, I’m a journalist,” he said. “I’m doing a field-trip, searching for information about Sangri-La.”

To my mind came memories in color sepia of readings about earthly paradises hidden in remote valleys of the Himalayas.

“Is Shangri-La real?,” I asked bluntly.

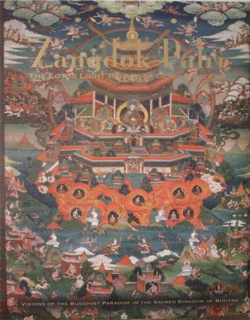

“The term Shangri-La became popular with the publication in 1933 of the novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton, echoing the fascination that the East exerted on Europe in the early last century,” he answered in a journalist-style. “However, it is true that in certain writings of the Tibetan Buddhist canon there are mentions to ‘beyuls’ (Pure Lands) and kingdoms such as Shambala where people enjoy long life and happiness.”

“In Sikkim?,” I interrupted.

“There are writings, paintings and legends that locate a beyul called Pemako in Sikkim, associated with the body of a deity.”

“Are you saying that the physical geography of Sikkim correspond to that of a deity?”

“Yup,” he said while nodding. “Moreover, the Tibetans believe the land they live upon is a ogress, a female giant lying on her back, and there are especially sacred places depending on her anatomy…”

“What?,” I exclaimed.

“The most sacred place of the Himalayas is at the western end of the range, at Mount Kailash, because it is at the brow of the ogress,” the reporter said. “One of the reasons I came to Yuksom is to try to contact with an old hermit monk who may have information about Pemako, another sacred site, in her genitals.”

“Are there any hermits around here?,” I asked.

“Yes, but nobody really knows how many.”

“Do you have an appointment?”

“Not really. The locals have told us that there is no need to apply because he knows in advance when someone comes in his search and, if he decides so, it is him who comes to you.”

“Unbelievable. But here it is not uncommon to meet monks. How will you recognize him?”

“We have been told that he has a long white beard, and always carries a long staff,” it was now the doctor who replied.

I was fascinated by these and other stories, but the cold and darkness of the night did not allow us much more conversation. We parted wishing us the best.

The next morning, I got up ready “to enjoy” a hiking day. My intention was to reach one of the holiest places of Sikkim, the Tashiding stupa, a hill located about eighteen miles south of Yuksom, where, the legend says, Guru Rimpoche himself spent a few days meditating.

When I was walking down the only road out of Yuksom, I saw in the distance the figure of a Tibetan monk moving in the opposite direction of mine. When we were about one hundred yards away, I noticed that the monk fit perfectly the description of the hermit we talked about last night: an old monk with long white beard who walked leaning on a long pole. I stood frozen for a while, and then I bowed on the ground, which is not uncommon among Tibetan people as a gesture of respect. When I rose up, the monk was gone!

I looked back and, there he was! about one hundred yards away… past where I was.

“Impossible, impossible,” I repeated to myself several times. I was tempted to chase him, but I didn’t dare; perhaps he was in his way to meet the couple with whom I had spoken last night. I resumed my way musing to myself, “It cannot take me more than ten seconds to do a full bow, so, a hundred yards ahead and another hundred yards behind, implies that the old monk had to walk at twenty yards per second, twice as fast as a professional sprinter!, and pass by me on the narrow road without me noticing him!”

I then remembered that the French writer and adventurer Alexandra David-Neels –whose work I admire deeply– wrote in her books that she had witnessed extraordinary feats while living in Tibetan Buddhist communities in the early nineteenth century, precisely in Sikkim. For example, she describes in detail a technique called “lung-gom,” which allows the practitioner to walk at impressive speeds. “Would that explain the strange occurrence I had just witnessed?” Looking at the outworldy landscape that surrounded me, that thought made totally sense.

One of the byproducts of practicing meditation is the development of spiritual powers, such as flying, having the capacity to transform the appearance, guess others’ thoughts, see and hear the heavenly realms, or have knowledge of past lives. Despite how spectacular or unbelievable these powers may seem, all genuine teachers warn about their potential danger. One must be very careful not to be tempted to direct the spiritual practice to the attainment and development of these powers, because not only do not lead towards a genuine realization but they may even become a source of obstructions, especially when they appear before the wisdom of the meditator is not mature enough to know how to properly use them, and he or she is not able to keep up the golden rule: never for personal gain. In fact, some false masters may use such powers to take advantage of those more impressionable.