Shengren

There is something unique here in Europe that is recognized in us by all other human groups, too, something that [...] becomes a motive for them to Europeanize themselves even in their unbroken will to spiritual self-preservation, whereas we, if we understand ourselves properly, would never Indianize ourselves, for example.

- Edmund Husserl, The Vienna Lecture

We cannot and we must not become Chinese, and at heart we also don’t want to. We must not search ideal or higher meaning of life in China or in any other thing of the past; otherwise we loose ourselves and adhere to a fetish.

- Hermann Hesse, Materialien zu Siddhartha

i. Significance

Do you know what a shengren is? The shengren is the single most important concept in Chinese tradition. Since the Europeans had not anything like it, but refused to hold the candle to China, they instead withheld the shengren and talked about some lesser versions of (Greek) philosophers or (Christian) holy men. The Anglo-Saxons soon found a slightly better translation, calling the shengren sages.

The Germans however, the descendents of the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation, never had a concept for sages and sagehood. In their effort to Christianize China, they called the shengren saints. With little regard for what was actually written in the Chinese Canon, the European imperialists engaged in a battle of control over China’s most valuable possession: its names.

This study is about sages, sagehood, sage culture, countries without sages, language imperialism, and the revival of China’s shengren.

ii. Methodology and Organization

Each chapter establishes the relevant facts and makes a crucial inference:

Chapter 1 – No Country for Sages: Germany had philosophers (fact); Germany had no sages [Weise] (fact); Germany does without sages (inference).

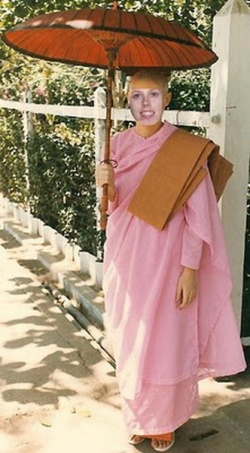

Chapter 2 – No Culture for Sages: Germany had no Confucianism, Buddhism, Hinduism or Taoism (fact); Confucianism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Taoism all had concepts for sagehood (fact); Germany had no concept for sagehood (inference).

Chapter 3 – Archetypes of Wisdom: The most common German translation of shengren) was “Heiliger” (saint) (fact); The most common English translation was “sage” [Weise] (fact); The most common English and German translations do not correspond (fact); One or both translations is/are inadequate (inference).

Chapter 4 – The Shengren in The Analects: The term shengren) appeared in all of the Confucian Classics (fact); It had not been adopted in European languages but instead translated (fact); The various sheng(ren) translations varied significantly from each other (fact); A competition for the most favorable translation occurred (fact); The original shengren would be terminated (inference).

Chapter 5 – Summary and Conclusion: “No one” was above Greek philosophy (fact); “No one” was wiser than the Christian God (fact); “No one” was above German bureaucracy and regulation (fact); A shengren was above Greek philosophy, indifferent toward the Christian God, and not subject to German bureaucracy and regulation, ergo he was “no one” (inference).

iii. Definitions

a) Philosopher and Sage: A philosopher is a wise man distinguished for wisdom and sound judgment; a sage is a wise man distinguished for wisdom and from experience.

b) Philosophical and Sagacious Approaches to Thinking: The philosophical approach to thinking emphasizes the acquisition of new knowledge; the sagacious approach to thinking emphasizes the accumulation of wisdom.

c) Language imperialism: Imperialism, according to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, is “the extension or imposition of power, authority, or influence” over another nation. Consequently, Language imperialism is the extension or imposition of names and terminology over another nation. Luther’s Bible translation is a good example, Hegel’s German Die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte (1830) is another. The former made the Bible German, the latter made world history German.

iv. New Concepts

1) Sage Culture: A sage culture is a culture that had sages and promoted sagehood; the opposite of sage culture is a no-sage-culture or No Country for Sages.

2) No Country for Sages: A terminology was required to define and describe the circumstances under which a society suffered (or fared well, depending) from a lack of sages and sagehood. Such a concept shall be called: No Country for Sages – Ch: 聖無所依 “Sheng wu suo yi” [simplified: 圣无所依. No Country for Sages is a freely-invented alteration of the Chinese idiom 老无所依 “Lao wu suo yi” [No Country for Old Men; lit: Old no place to lean against], inspired by William B. Yeats’ poem Sailing to Byzantium (1928) and the award-winning movie picture No Country for Old Men (2008) by the Coen brothers. The Chinese idiom 老无所依 Lao wu suo yi or “No Country for Old Men” refers to a society that lacks filial propriety and is usually said of elders, 老 “lao”, who, despite their life experiences and spiritual wisdom are unwanted, with no meaningful purpose in life, and thus helpless. It is to pity them.

The modified idiom No Country for Sages refers to a society that lacks sages, 圣 sheng, and also lacks a culture that would nourish them. The opposite of No Country for Sages is a ‘sage culture’, or ‘sage society’.

In sage-culture taxonomy, Asian societies that managed to nurture Confucian, Buddhist, Hindu, Taoist, or Shinto traditions should be called sage cultures. Pre-Socratic Greek society was a sage culture, too, but more to that later. On the other hand, Germany, a young European nation, was and still is No Country for Sages. Not only does Germany disregard the sages, the German word for sages, “die Weisen”, is not a proper title or name for any of its great thinkers to this day. Great thinkers in Germany were considered Philosophen and Dichter (philosophers and poets); and the holy men of Christianity were called Heilige (saints), a term loaded with (European) historical baggage but without reference to wisdom or sagacity.

Projecting their own culture onto others, German scholars refused to call – as a general rule – the great thinkers of Asia such as Confucius and Laozi by their real names, shengren, or appropriate synonyms like “sages” or “Weise”, but instead assumed their European traditions and called the shengren the “Philosophen“ or “Heilige” instead.

That habit has continued for over three hundred years now irrespectively of what was and still is really written in the Confucian Classics: 圣人sheng(ren). In addition, German-language scholarship is unimpressed by international scholarship and the more appropriate English translation “sage“. As will be demonstrated in the course of this text on so many levels then: No Country for Sages refers exclusively to Germany.

3) The Four Classes in German Orientalism: The Four Classes – philosophers, orientalists, practitioners, and sponsors – controlled, protocolled and regulated the influx of Oriental ideas and concepts into Germany. Collectively, partly consciously and partly unconsciously, they tried to intellectually and psychologically describe, define, and dominate a myriad of Eastern thoughts, and, at the same time, by fabricating European-centered universals, guard against the otherwise unavoidable Easternization of the German-speaking world.

4) Holy Confucius! is a paradox, like a secular saint; or an absurdity, like Sage Jesus or Moses the Scientist.

v. Totum pro parte

Throughout the text, often “Confucius” – totum pro parte – stands for “Chinese shengren”, “sages” for “Oriental sages” in Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, etc., or “Buddhism” or “Confucianism” stand for “sage culture”, “China” for all “Sino-Tibetan cultures”, “Plato” for “Greek philosophy” (as he hated the sages), etc. Such generalizations are at times a necessity to compare East and West culture-wise. It is also a good principle to argue and stick to the main concept, “sages”, not to quibble over its variations, because, as a general rule, Germany in any case is without Buddhas, bodhisattvas, rishis, shengren, and die Weisen.

Shengren in a way stands symbolically for all foreign terminology sacked by the West.

Enlightened beings