Machig’s Story

Machig’s Story

Right now you have the opportunity.

Look for the essence of mind--this is meaningful. When you look at mind, there is nothing to be seen.

In this very not seeing, you see the definitive meaning.[1]

Below is a brief overview of the life of Machig Labdrön and the influences that led to the development of her lineage. She was born in 1055C.E., at a time of great innovation, a kind of religious renaissance in Tibet.

Machig's life began as a cherished and privileged protégé in the Buddhist hierarchy of her time, she gave up her privilege to become a wandering yogini and later a mother.

This move away from monastic institutions and a life of celibacy contributed to her losing her previous social status.

She continued to heed her deep calling to practice the dharma, and eventually she left her children with her husband for several years and returned to her teachers, reuniting with them.

Eventually, Machig became her teachers’ teacher.

Machig was never a hermit and she spent most of her life in service of her students.[2]

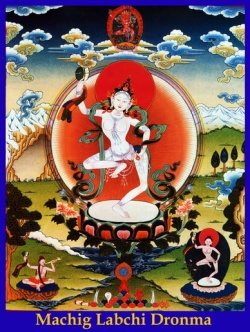

Machig’s life and her accomplishments were prophesied in both Sutra and Tantra traditions by the Buddha and also by Guru Padmasambhava, the embodiment of Prajña Paramita, goddess of wisdom, and of Tara, the female Buddha of compassion.

Machig was the 107th human incarnation of Prajñaparamita and Tara.

In the Do Tang Nyik Jaypa Sutra, the Buddha said:

In the future when there is great need for human beings, the emanation of Mother Goddess of the Victorious Ones,

in the North in a place called Lab a person whose name is Drönme will be born, and she will benefit numberless beings through the stages of visualization and completion (Sampannakrama and Utpattikrama). She will wander in towns and cemeteries.

In the [[Jampel Tsawai Gyud] Tantra]], the Buddha prophesied:

“When my teaching is thin like a tea leaf, the embodiment of the Great Mother, whose name is Labdrön will come and her activity will be far reaching.

Anyone who is involved with her activity will be liberated.”

From Guru Padmasambhava, in a prophecy called Tenpa Cir Lung (The General

Prophecy for Buddhism), it says:

The Manifestation who will cut through all aspects of negative thoughts, who will make them rootless, cutting through them so finely they will never grow again, whose name is Labji Drönma, will come to a place called Zangri (Copper Mountain).[3]

Machig had been an Indian yogi in her previous life.

As a result of a series of visions, this yogi left his body in a cave in India and his consciousness traveled to Tibet.

His consciousness entered the womb of a kind noblewoman, Bumcham.

The night she conceived, Bumcham, her first daughter and a neighbor all had extraordinary dreams.

When the baby was born, she had many special signs and was surrounded by luminosity, including a third eye shape in her forehead.

Considering this a deformity her mother hid the baby behind a door, afraid of what her husband would say.

The father had heard the baby had been born and insisted on seeing her.

He saw a sacred letter AH written very finely in her third eye and saw that she had all the signs of a wisdom Dakini (feminine wisdom being).

Machig grew rapidly and was extremely precocious, before she was three years old, she knew many mantras and she liked to do prostrations and make offerings.

She learned to read easily by the time she was five by just being shown the letters.

By the time she was eight, she could recite the Eight Thousand Line Prajña Paramita Sutra twice in one day.

The governor of the district heard of her and tested her publicly.

She was able to recite and explain the meaning of the sutra.

While her mother was so shy that she could not speak, the

young Machig spoke right up.

The governor was impressed and gave her the name Labdrön,

Shining Light from Lab (the area she came from) declaring she was a wisdom dakini, and recommended that she be protected from the influences of negative people.

Then returning home, Machig Lapdrön with her mother and sister and spent five years studying and reciting the extensive, medium and abbreviated form of the Prajña Paramita Sutra.

This Sutra was considered the most sacred of the Buddha's teaching, such that touching it or viewing it could bring great blessings and healing.

Having it recited was considered to be a great blessing, and it was the number of times it was recited, not so much understanding the words that was considered of value so a fast reader was very valuable in this occupation.

When Machig was thirteen, her mother passed away, and she and her sister began to study with various teachers.

When she was sixteen, Machig began to study with Lama Drapa, who taught her in great depth about the Prajña Paramita Sutra.

He then asked her to stay with him for four years as his official reader.

She agreed and became the reader for his monastery, traveling to the homes of lay people and reciting this Sutra.

In this way, she immersed herself in these teachings while serving her teacher. Around this time her sister entered retreat and subsequently passed away.

===Prajña Paramita===

Machig's close identification with the Prajña Paramita teachings from her childhood extended throughout her life.

It is important to understand Prajña Paramita because Machig's teachings are based on it in important ways.

First, the whole practice of Chöd is founded on Prajña Paramita.

The aim of the Chöd practice is to overcome the ego’s self-clinging so we can perceive the true condition of self and phenomena, empty of our preconceptions, where there is

no self and no other. In addition, Machig’s understanding of the nature of demons came in part from rereading and studying the Sutra.

The Prajña Paramita, is a profound philosophical doctrine focusing on the awakened state. In later times, Prajña Paramita was personified as female Buddha.

The underlying philosophical principle had its’ origins in Indic South Asia and began to emerge around the time of Christ.

In this emerging Mahayana Buddhism, Prajña Paramita was called the Great Mother, the matrix from which all awakening occurs.

Therefore, she was the mother of all the Buddhas as the source of all enlightenment; this became one of her most common epithets.

This is the first time we see a primal feminine principle in Buddhist thought.

Prajña Paramita has several meanings: first it refers to the non-dual gnosis of the awakened ones.

Secondly, it is the path leading to the non-dual, or the knowledge or particular intelligence leading to awakening.

Third, it refers to the texts themselves which reveal this knowledge.

And finally, it refers to the embodiment of this wisdom as the first Buddhist goddess.

In all cases Prajña Paramita was referred to as feminine but at first as a feminine principle and then later as an actual goddess.

The term prajña is usually translated as transcendental wisdom, meaning the wisdom that transcends ordinary reality and perceives actuality.

There are many kinds of prajña, or wisdom, but only Prajña Paramita is perfect wisdom, or wisdom that goes beyond ordinary perceptions

and knowledge, and sees right into the heart of everything.

The word paramita means perfection or that which goes beyond.

There are six paramitas typically taught as the activities to be cultivated to reaches the perfection of awakened mind (also called bodhicitta), the paramitas are: generosity, patience, discipline (or ethical conduct), joyful diligence, meditation and finally prajña.

The Prajña Paramita Sutra is the most important text of Mahayana Buddhism, which emphasizes the doctrines of emptiness and compassion.

This text formed a foundational doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism which then spread to China, Tibet, Japan, and Korea.

The text remains a core part of the Mahayana traditions throughout Asia.

The roots of Prajña Paramita can be traced to a visionary scholar, Nagarjuna, who lived

in approximately 100 C.E. in the area of Andra Pradesh in southwestern India whose people were descendants of the ancient matrifocal Dravidian people.

This might have influenced the understanding of Prajña Paramita as a female embodiment of wisdom.

Nagarjuna received numerous Mahayana texts including the Prajña Paramita Sutra from snake-like water spirits, nagas, who had hidden them under the water in the lake near where he meditated.

The nagas invited him under the water where he received this treasure of wisdom that launched the new wave of Buddhism called Mahayana (aka the Great Vehicle).

Edward Conze a scholar who spent his scholarly life focusing on the Prajña Paramita literature drew some remarkable parallels and possible connections between Prajña Paramita and the western embodiment of transcendental wisdom, Sophia.

He saw that both Sophia and Prajña Paramita are feminine embodiments of wisdom that emerged and were popularized at the same time.

According to Conze, therefore there is a feminine wisdom principle at the root of western culture as well as forming the base of Mahayana Buddhism.

This is a significant connection because it is through this feminine wisdom goddess that Machig's life and teachings are linked to our own western cultural roots.

Conze suggests both that this could be a synchronistic simultaneous emergence from the human collective unconscious (in the Jungian sense) and he went on to explore historical connections.

For example, Conze describes a Buddhist stupa in Amaravati, Andra Pradesh, India, where the great scholar Nagarjuna had lived and where he had discovered the Prajña Paramita Sutras.

This stupa combines Dravidian architectural style with Greek elements[4], from this, Conze proposed a possible historical link between Greek and Buddhist thought. Of Amaravati, he wrote:

In this area both Dravidian and Greek influences made themselves felt, and Grousset has rightly called the Stupa of Amaravati a 'Dravido-Alexandrian synthesis'.

In view of the close analogies which exist between the Prajña Paramita and the Mediterranean literature on Sophia, this seems to me significant…and the matriarchal traditions of the Dravidians may well have something to do with the introduction of worship of the 'Mother of the Buddhas' into Buddhism.[5]

Although this architectural confluence suggests a connection between East and West at a time when Sophia was a prominent presence in the western theology, it is not yet clear whether historically there was a direct interface between early Mahayana Buddhists and the tradition of Sophia.

In any case, there was a remarkable similarity in the philosophical understanding represented by these important female embodiments of absolute wisdom occurring at the same time in the East and the West.

This form of the divine feminine emerged during the Neolithic era where the goddess was the image of totality;

life came from her and returned to her, and she embodied “the door or gateway to a hidden dimension of being that was her womb, the eternal source and regenerator of life.”[6] Sophia, like Prajña Paramita, was depicted on a lion throne, as were all goddesses before her.

This notion of the great mother was also present in the ancient matriarchal Dravidian culture evincing even more possible layers of interrelatedness.

Statues of Prajña Paramita as a Buddhist Goddess were first observed in India by the Chinese pilgrim Fa-shien in 400 C.E. In Tibetan, she is later known as Yum Chenmo.

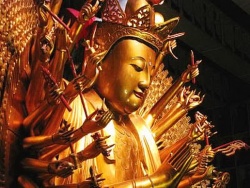

Sophia, the Holy Spirit of Wisdom, was the inspiration for the divine marriage, reunion of dualities. And Prajña Paramita became the female aspect of wisdom that unites with skillful

means, upaya, to create the sacred marriage of non-duality in Tantric Buddhist imagery of Yab Yum, the masculine and feminine in sexual union.

The association with prajña is so strong that the female Buddhas represented in these unions are called the prajñas to make this link explicit.

Another connection between Sophia as the embodiment of gnosis and Prajña Paramita is epistemological.

The word prajña in Sanskrit and gnosis in Greek have the same root.

The word gnosis derives from the root gno-, "to know, cognize, discern".

This Greek verb-root matches the Sanskrit jña-, which carries the same meaning.

In Buddhism, prajña is the profound knowing which indicates a direct insight into the true nature of reality, or wisdom.

The text of the Prajña Paramita Sutra, its doctrine, and virtues were later represented by a goddess known as Yum Chenmo, the Mother of All the Buddhas.

So Machig would have known her in this form as well as the more abstract earlier teachings on wisdom.

Prajña Paramita was a highly developed form of the mother goddess who had been with humanity from its inception, and later, in the Indic context, she became representative of direct insight into the ground of being.

This insight, accomplished through meditation and which is beyond words, comes from turning the mind to look at itself.

The process turning and perceiving an ineffable luminous awareness is Prajña Paramita.

The stabilization of this indescribable awareness is what gives birth to enlightenment, and thus she was described as the “mother or womb of all the Buddhas”.

Here is the most well known quote from the Heart Sutra, an essential discourse on Prajna Paramita:

Form is emptiness, Emptiness is form,

Form is not other than emptiness, Emptiness is not other than form.

The Prajña Paramita teaches that, once we let go of conceptual thought, emptiness is revealed as fullness, not a dead nothingness, but a vibrant womb of awareness.

The teaching on offering one's own body as nectar (as in the Chöd) shows us this is not mere self-sacrifice leading to depletion (as many women experience), but an open-hearted generosity based on an understanding of the essential impermanence and lack of a discrete self in oneself or any other form.

It was from this state that Machig was able to offer her body as food to the army of demons during one of her early empowerments and which then formed the basis for her Chöd practice. In her study of the Prajña Paramita, Machig was not only accessing a fundamental

Buddhist teachings but also linking to the divine feminine with which she later more consciously identify herself. .

During the time that Machig was receiving these in-depth Prajña Paramita teachings, a great Indian yogi named Dampa Sangye came from India because he’d had a vision of her previous incarnation being reborn in Tibet as a woman.

The night before they met, Machig also had a dream about him.

In the early morning she went out into the courtyard of her dwelling and ran into him.

She began to prostrate to him but he stopped her and touched foreheads with her, a sign of equal status and deep connection.

She asked him how she could help others and he replied:

Confess all your hidden faults.

Approach that which you find repulsive.

Whoever you think you cannot help - help them. Anything you are attached to let go of it.

Go to places like cemeteries that scare you. Sentient beings are limitless as the sky.

Be aware.

Find the Buddha inside yourself.

In this teaching we find essential instructions that were later articulated in her Chöd teachings. Dampa became an important teacher for Machig, and she received extensive initiations and oral transmissions from him.

According to many scholars, the philosophical lineage of Chöd came from Dampa and was then transmitted to Machig who made the practice her own.

Shortly after this meeting, a great yogi named Lama Sonam Drapa learned of Machig.

He had been a famous teacher, but had become disillusioned by the lack of genuine students.

As a result, he had become a wandering yogi, walking through the mountains and to the sacred places of Tibet.

He decided to come to test her.

When he arrived he said to her: “You are very learned in Prajña Paramita, the perfection of profound knowing, but do you understand the real meaning of it?”

She replied, “Yes, I do.”

He said: “Then explain it to me.”

So she explained everything she had studied and understood through meditation in great detail.

Then he said: “You are obviously very intelligent, but you don't seem to have made the teachings part of you.

Everything you said was correct, but the most important thing to realize is this:

If you do not grasp with your mind, you will find a fresh state of being.

If you let go of clinging, a state beyond all conceptions will be born. Then the fire of great prajña will grow.

Dark self-clinging ignorance will be conquered.

The root of the teachings is to examine the movement of your own mind very carefully. Do this!”[7]

Machig went back to the Prajña Paramita Sutra, and reread it in light of what Lama Sonam had said.

She came across a section about the nature of demons and was so profoundly affected by it that she reached a profound understanding of the nature of reality.

This was a turning point in her life, and it was also the moment when she understood the nature of demons.

Most simply she defined demons this way:

Attachment to any phenomenon whatsoever, From coarse form to omniscience,

Should be understood as the play of a demon.[8]

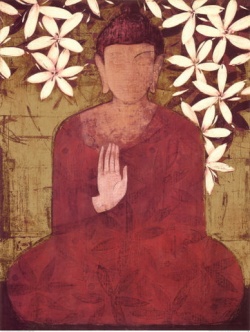

Maras and Demons: Obstacles to Enlightenment In Buddhism, the idea of a negative presence accompanying those seeking enlightenment goes back to the Buddha, who was followed throughout his whole life by a shadowy figure called Mara.

Mara is the energy of resistance, laziness, sensual desire, craving, anger, hope, fear, and the longing for praise and honor that arises and sidetracks us from the goal of awakening.

The Buddha had a relationship with Mara as a personified being and he actually addressed Mara as a person and Mara responded.

Mara always knew the Buddha’s weak points and approached him at the most difficult moments.

The night Gotama, the future Buddha, decided to leave his princely life, abandon his wife and newly born son, and renounce all claims to worldly power, Mara made his first appearance.

While everyone in the palace was asleep, Prince Gotama called his charioteer, Karnataka, asking him to wrap his horses’ hooves in cloth to muffle their sound and to accompany him on foot. They managed to escape the palace undetected, and as they were

leaving climbed a hill that gave the future Buddha his final look at the moonlit palace with oil lamps glittering in the windows.

At that moment Mara appeared in the air in front of him.

“Do not go,” he said. “In seven days you will achieve universal sovereignty.”

Notice that Mara wasn't offering this tremendous gift right then, on the spot, but in seven days; close enough to seem immediate, but just out of Gautama’s grasp.

Mara was playing on Gautama’s temptation to pursue the happiness and success that lay just around the corner, in just a few more days.

We all can identify with this form of Mara and may even have ideas—like when we make a certain amount of money, or get a certain job—there will be a big payoff, and we will attain the ultimate power we always wanted. And, that this payoff might be just days away.

In addition, Mara also offered the young Gotama the ultimate in worldly status, but the Prince recognized the trap.

Gotama said, “Mara I know you. Rulership of this world is not what I seek, but to become a Buddha.”

This statement “Mara I know you,” is key in understanding how Mara works and how to deal with him.

He works on us even though we may not recognize distractions and obstacles as Mara.

Then first most important moment is when we recognize what is happening and we can say, “Ah, Mara I know you.”

Mara appeared at several other times during the Gautama’s life, including several times after his enlightenment.

Mara is in all of our fear and clinging.

Mara is the one who limits us, or blocks us from awakening to our true nature.

By Machig's lifetime, about 1500 years after the Buddha, the notion of Mara as a personified generalized demon had been broken down into four types of maras, or categories of obstacles to enlightenment.

These begin with the mara of our psychophysical constituents. The second is the mara of destructive, poisonous emotions, which can affect us not only mentally but also physically (think depression, anger, jealousy, etc.).

The third mara is being so caught up in trying to have a luxurious life (just one more margarita by the pool and then I'll meditate) that we miss the opportunity to wake up.

This is called the mara of the son of the gods.

The fourth mara is death, which is an obstacle that clearly limits us all; even the Buddha was subject to death.

As we age we can feel the grip of this mara tightening. We are all pregnant with death, and at some point the due date will arrive.

We may have long pregnancy or a premature delivery, but one way or another it's going to happen.

It was in her reading about these four maras that Machig had her enlightenment experience.

Afterwards, she radically changed her way of life, and set out on the path that eventually lead to the formulation of the Chöd practice based on overcoming the four maras, which Machig categorized in her own unique way.

Until this time, she had been living in the rarified atmosphere of the monastery close to her teachers, wearing elegant silk robes and eating only pure foods.

But after her epiphany she became a wandering yogini, wearing rags, living with beggars and lepers, and staying anywhere.

After this Machig received further teachings from Dampa Sangye, who recognized her true lineage and explained to her that she was descended from Prajña Paramita, the Mother of all the Buddhas.

Then he told her about her past life in India, and that there was a prophecy in several ancient texts that in the age after the Buddha’s death there would be an emanation of the Mother of all the Buddhas in the northern snow country (Tibet).

According to the prophecy, her teachings would spread widely and endure a long time.

It is likely that Machig received Mahamudra teachings from both [[Lama] Sonam]] and

Dampa, and these teachings formed the second most important spiritual basis for her Chöd teachings.

The Mahamudra is a method of directly perceiving the nature of Mind.

Mahamudra developed after Prajña Paramita but with strong influences from it, arising with Tantric Buddhism around the ninth century coming into Tibet in the eleventh century. Mahamudra places a little less emphasis on negation than later Prajña Paramita, and a little more weight on the union of the emptiness and appearances.

In this wonderful “Song of Mahamudra,” by the great master of early Mahamudra Tilopa, you will hear distinct echoes of Prajña Paramita teachings:

The void needs no reliance, Mahamudra rests on naught. Without making an effort

But remaining loose and natural,

One can break the yoke, gaining liberation. If one sees naught when staring into space, If with mind one observes mind,

One destroys distinctions

And reaches Buddhahood . . . .

Though words are spoken to explain the void, The void can never be expressed.

Though we say, “the mind is a bright light,” It is beyond all words and symbols. Although the mind is void in essence,

All things it embraces and contains. . . .[9]

Motherhood

After Machig's meetings with Dampa and Lama Sonam, she was sent to read the Prajña Paramita Sutra in the home of a family connected to her teacher.

When she arrived, she had a dream about a red dakini with one eye who told her she should unite with an Indian yogi named Töpabhadra and this would create the union of wisdom and skillful means.

Later the same night she had another similar dream, of a blue dakini who told her this union would create a lineage and would cause the teachings to spread.

The next morning at dawn, a girl arrived, riding a white mule. She had been sent by the Indian yogi Topabhadra who was in Tibet.

The girl said he was a great yogi and he had invited Machig to visit him.

Machig rode on the mule led by the girl and met Topabhadra at the home of one of her patrons. After seventeen days of discussing Dharma and telling stories about India, Topabhadra came together with Machig in union.

This experience is described in her biography as a union of wisdom and skillful means.

Because such a bright rainbow light suffused the whole house and the source was coming from the room they were in, the patroness of the house came to see if the shrine had caught on fire.

When she opened the door all she could see was brilliant red and white spheres of light fused together in the middle of the room (in Buddhist Tantra the red essence symbolizes the feminine and the white the masculine).

The patroness realized what was happening and kept what she saw a secret.

Seven days later Töpabhadra went on pilgrimage, and Machig continued to read the Prajña Paramita Sutra.

But she was concerned that this relationship might cause disruptions and obstacles so she went to see her teachers, Lama Drapa and Lama Sonam.

They advised her to stay with Topabhadra.

Lama Sonam told her that she and Topabhadra had a karmic connection and weren't breaking any religious vows; he had also had positive dreams about this union.

So, when she was twenty-three Machig went to live with Topabhadra, and the following year her first son, Drubpa (meaning fulfilled) was born.

Because the people of central Tibet where they had been living criticized and shunned the couple, they moved to another area and after moving again she gave birth to a second son named Drupse. This was probably the most difficult time in her life.

Tibetans generally like their spiritual leaders to act differently than ordinary people, and up to this point Machig had been living as a nun and although there is

discussion about whether or not she was ever fully ordained, the monastic establishment and lay people had great respect for her and high hopes for her development as a great teacher.

Then suddenly, she had an Indian yogi lover and their precious pure nun was having children.

They were disappointed and unable to see this as an important part of her development.

When Machig was thirty, she gave birth to a daughter on a mountain pass “where the dakinis gather” right after performing an offering ceremony.

They called her '[Ladüma]] (Pass Gathering Girl).

According to her biography, Machig’s teachers encouraged her to unite with Topabhadra to create a lineage, but this doesn't make sense because most teachers had lineages that came through their disciples, not their children.

Perhaps she needed a consort to work with previously unknown pathways to bliss that allowed her to then bring her teachings forth from the untying of knots in her subtle body.

Certainly she developed a whole body of sexual yoga practices that could not have come into being without this experience.

This was not the only legacy of motherhood.

After all the fame and prestige she had enjoyed since childhood, now Machig had to endure public humiliation.

Having three children and being a homeless yogini wandering with her husband and babies on the 12,000-foot plateau of Tibet with its sub-zero winters, also would have challenged her and developed in her qualities that most likely would not have developed had she remained in the refined atmosphere of her teacher's establishments as the darling of the monastic and lay community.

She would have learned through these trials the fickleness of praise and blame and she have tested her philosophical learning against the hard facts of life as a poor scorned mother.

Perhaps Machig needed to actually be a mother, to experience the challenges and attachments of this very humanizing experience, before she could truly know her connection to the Great Mother and become the mature woman teacher she later became.

In any case, she did not stick with this role for more than ten years.

When she was thirty- five, Machig “showed signs of being weary of cyclic existence” and left her children with their father and returned to see her teachers.

In her biography it says she did this because of indications from the dakinis.

Again we have to read between the lines of her story, and imagine this was not an easy decision and her longing for the depth and quiet of a life dedicated to spiritual practice and her sense of spiritual destiny must have overridden her attachment to her children.

When she returned, she asked Lama Sonam for the ritual for awakening the heart-mind of Bodhi.

He replied, “You don't need to have awakening mind conferred on you.

You are the indisputable great adept, the great Dharma Master.

You are the Great Mother, progenitor of all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas.

You are the Great Eyes with mastery over Sutra and Tantra.

You are the Great Source and Treasury of All Dharma.

You don't need an awakening mind ritual.

In your presence, I am like a star beneath the moon.”[10] He then said, “You should go to Central Tibet.

There is a red mountain the color of copper where you will help many beings who are to

be tamed.”

She also practiced in 108 charnel grounds and wandered on pilgrimage for several years.

Before proceeding to this place where she eventually settled and established her Dharma seat, her other teacher, Dampa Sangye came to see her.

She asked him for further teachings, but he said that he had already given her his most profound teachings, but he still gave her extensive teachings.

Eventually she moved to the prophesied place: a red mountain set over a wide meandering river called Zangri Khangmar (Red House on the Copper Mountain).

There, a couple whose death had been predicted within a year, asked Machig for help.

When she helped them avert this fate, her reputation spread throughout Tibet.

By the time she was forty, stories about her excellent qualities had spread widely.

As a great yogini she taught the learned teachers of Tibet and became legendary.

At this time she fully formulated the Mahamudra Chöd, and became known as Mother Lapdrön.

It was said that through her practice of Chöd she could heal 424 kinds of diseases and subdue 80,000 kinds of demonic forces.

When she was forty-one Machig went into retreat in a cave, and the female Buddha Tara, appeared to her surrounded by many dakinis.

Tara made a prophecy about Machig and her followers, and emphasized that Machig would develop a secret “vanquishing conduct,” which is one of the ways Chöd practice is defined.

After this, Machig praised Tara and said: “You have been very kind to me and have given me power.

I am just a weak stupid woman, but now I have become someone who can benefit others because of your grace.”[11] Then Tara said that Machig’s teaching would spread and she would attain enlightenment.

She also described her spiritual lineage starting with Yum Chenmo (Prajña Paramita) and descending to various female emanations and finally emanated as Machig in Tibet.

As Tara told all this to Machig, immeasurable light spread from her heart and then dissolved into Machig's heart.

Then Tara and her retinue vanished into the sky, just as dawn broke.

After this, Machig was reunited with her children, who were brought to her by Topabhadra.

Her younger son, who was fifteen, and her daughter, who was ten, had already begun training, and already knew several versions of the Prajña Paramita Sutra and several other practices.

Her eldest son had gone off and was married. And her younger son was sometimes overcome by madness and blacked out.

To resolve this Machig sent him to sleep for seven days in a charnel ground, where bodies were cremated.

Odd as this may seem as a cure for madness,

he returned cured, so she decided to confer many teachings on him and had him ordained as a monk.

He became her foremost disciple and spent fourteen years in a cave under her guidance. Later her eldest son returned to her and also became a lineage holder.

Passing the Test

Machig's fame spread all the way from Tibet to India. Her Mahamudra Chöd proved revolutionary, and drew an instant following.

This was especially surprising because at the time, Buddhist theology flowed almost exclusively from India to Tibet, and not the other way around.

a result she caused quite a stir among the higher-ups in Indian Buddhism.

According to her biography the pandits in Bodhgaya held a meeting to discuss her.

They said:

All true Dharma comes from India but this teaching called Mahamudra Chöd did not, even though Mahamudra does.

This teaching has spread from Tibet to Nepal.

Even the Nepalese are receiving teachings from this woman with three eyes; she teaches the Chöd, which they claim can overcome the forty sicknesses and the 80,000 obstructions.

This three-eyed woman claims to be an incarnation of the Prajna Paramita Dakini, but more than likely she's an emanation of bad demons.

It will probably be difficult to conquer her.

But if we do not, she will destroy all of Tibet and then invade India.

We must send a party to check up on her.

Everyone agreed that since Machig seemed to be a dangerous magician they'd better send their most powerful scholar yogis.

So three accomplished yogis flew to Tibet “like hawks in search of a little bird,” using a spiritual practice that allowed them to travel through the air, and they

landed on her roof terrace.

When Machig came out and greeted them in their own language, they said, “How is it that you know our language?”

She responded, “Because I have often been Indian in previous lives.”

And they said, “You mean to say you remember your previous lifetimes?”

She answered, “Yes, I remember them all,” to which they replied, “Well, why don't you tell us about them."

She said, “Fine, but what I’d like to do is to gather all my disciples from here and Nepal and find translators.

Then everyone can hear what I have to say, otherwise only you will be able to understand.”

So she sent fast walkers all over Tibet.

Fast walking is a practice using spiritual powers and control of the inner winds to travel long distances without touching the ground with your feet.

It took about a month for everyone to arrive at Machig’s residence, since not everyone knew fast walking.

They arrived with a month's worth of supplies and Machig began to teach over 500,000 people.

The pandits engaged her in debates that were widely translated into all the languages of the people who were attending from various parts of Tibet and Nepal.

No matter how hard the Indians tried, they could not defeat her.

Her scholarly understanding was amazing and in addition, her direct realization of enlightenment was undeniable.

Even so they kept pestering her about her previous live and asking how she could prove the authenticity of her teachings.

She finally said to all present:

Listen carefully, all of you assembled here.

The Indians have no confidence either in myself or my teachings.

So they've sent these acharyas here to test me. “Let's check this doctrine of yours.”

They tell me and “if you do indeed recollect your previous lives, well, let's hear about them!”

Obviously if I can't provide sufficient proof and justify my Dharma teachings, not only the people in India, but also my own disciples, as well as all of you who have come here and everyone else in the Land of Snows will lose confidence in my instructions.

If I don't give an account of my previous lives, no one will believe me anymore. So all of you listen carefully![12]

Then she gave her full cycle of teachings and described her lineage and her previous incarnations.

When she got up to her last incarnation she then described the cave in Southern India called Potari where she had left her body, potentiated against decay. In that cave, she said, they would find her body from her previous life, and it would be youthful and healthy looking.

She told them to cremate the body with white sandalwood and predicted exactly what would be found in the ashes, including bas-reliefs of five male and female Buddhas, an image of the Great Mother, and a white and green image of the goddess Tara.

She said that if events did not proceed just as she had described with no variations, then everything, including her teachings, could be considered false.

And so the pandits left with Dampa and by means of fast walking they went to Potari, found the body, and created a huge pyre of sandalwood and cremated the body of Machig Labdron’s previous incarnation.

In the ashes they discovered various relics, all precisely as Machig had predicted. Dampa returned to Tibet with the relics, and people from all over Tibet came to see them and receive blessings.

After this final vindication of Machig's teachings, they spread widely throughout Tibet, Nepal, and India. Machig was now fifty-two.

The Indians requested that she go to India to teach, but she said she'd had many incarnations in India and would stay in Tibet.

However, she would send her Dharma system that originated in Tibet, the Chöd practice.

This prompted her to write some of her key works, which were then sent to India.

The rest of Machig’s life was spent mainly at her seat in Zangri Khangmar, teaching her numerous disciples, 1,263 of whom reached enlightenment.

She also healed many with the Chöd:

423 lepers were completely cured, their flesh restored to its previous condition.

She passed into bliss at the age of ninety-nine. All of her children became lineage holders, particularly her son, Tönyon Samdrup.

Before she died she gave a beautiful teaching called “Machig's Last Instructions” which appears in full in an appendix at the end of the [[book

When we look at Machig's life we see her self-doubt balanced by an underlying sense of destiny.

She was at once very human, struggling with questions about whether to give up her spiritual life and enter a relationship, whether to leave her children or not, and at the same time she was clearly an extraordinary being, recognized from childhood as a divine incarnation of the Great Mother Prajña Paramita.

When Tara appeared before her, predicting her children would be lineage holders and that Machig herself would be a great dakini, Machig still referred to herself as a “weak stupid woman".

Yet later she was able to confidently confront the patriarchal Buddhist establishment in the form of the three pandits who arrived from India to test her, debating against them publicly with her entire reputation at stake.

Women have so few voices in their lives that affirm their wisdom and spiritual potential and we rarely have a female lineage that we can draw strength from.

The goddess Tara and Dampa Sangye told Machig her lineage, and this gave her ground to stand on, confidence about who she was.

A lineage is like a family tree but of a spiritual nature.

We all have a spiritual lineage of some kind. When we know our spiritual roots, we have a source to draw on, as sense of roots and an inspiration to draw on.

Figuring out your spiritual lineage, whether you are male of female, and whether it is straightforward or eclectic can be an important step in clarifying your own path and gaining confidence.

In the story of Machig we find the threads of what became the Mahamudra Chöd.

When I sat in the monastery of Swayambhu in Nepal with the Lama and the young monk translator, hearing Machig's story for the first time, it was less than two years after the death of Chiara. Machig’s life story and the dreams that had brought me to her story offered me a light at the end of a dark tunnel.

Then I knew I had a deep connection with this dakini in my own spiritual lineage and that she had called me to bring forth her story to the wider world.

It was the first

time I had heard the biography of a great woman teacher, although I had been doing Chöd off and on for ten years I'd only heard bits and pieces of her story.

It was something I needed, and it felt like a key that would unlock a treasury.

[1] From “Machig's Last Instructions” in Jerome Edou's Machig Labdrön and the Foundations of Chöd, Snow Lion Publications, 1996, p.169.

[2] For complete translations of her story see: Women of Wisdom, Allione, (1984, Routledge and Kegan Paul; 2000 Snow Lion Publications), Machig Labdrön and the Foundations of Chöd, Edou, 1996, Snow Lion Publications, or Machik's Complete Explanation, Harding, 2003, Snow Lion Publications).

[3] These Sutric references and the prophecy of Padmasambhava came from a talk given by Tai Situ at Samye Ling Tibetan Monastery in Eskdalemuir, Scotland in 1988, an introduction to Chöd, found on www.quietmountain.org.

[4] Conze, Edward, The Prajña Paramita Literature. Munshiram Manoharlal Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, 2000, p. 2. [5] Ibid.

[6] Baring, A. and Cashford, J, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image. Viking

Penguin, 1991, p. 611. [7]Allione, Women of Wisdom.

[8] From the life story of Machig in Jerome Edou's, Machig Labdrön and the Foundations of Chöd, Snow Lion Publications, 1996 p. 162.

[9] C.C. Chang, The Teachings of Tibetan Yoga, University Books, New York, 1963, p. 25. [10] Harding, p. 81.

[11] Allione, Women of Wisdom, p. 196.

[12] Edou, Machig Labdrön and the Foundations of Chöd, p. 160.