Sunyata as the complementarity principle in Buddhist thought

Tetsunori Koizumi, Director

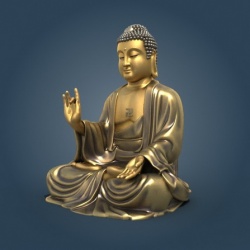

Sunyata, or “emptiness”, is the central idea in Buddhist thought. What this idea means, however, is elusive and tends to escape clear understanding even when it is translated into a statement in ordinary language: “Everything in this world is empty as it lacks intrinsic existence.” Translating it into a statement in the language of modern science might make the meaning of sunyata more transparent and accessible to the modern mind. While the Buddha himself would have objected to such an intellectual endeavor as it takes us away from the experiential understanding of his teachings, it is to be recalled that the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths as expounded in his first sermon was a logical system consisting of four propositions about the nature, cause, cure and treatment of dukkha, which is the basic condition of life in this world.

The four propositions that comprise the Four Noble Truths are derived from and reflect the Buddha’s view of the world, which, as it turns out, is not unlike a systems view of the world developed by modern systems scientists, who see the world as consisting of entities and relationships among them. To the extent that there exists correspondence between the Buddha’s view of the world and that of systems scientists, we can perhaps gain valuable insight into the Buddha’s thought by rephrasing his ideas in the language of systems science.

In order to rephrase the Buddha’s thought in the language of systems science, we introduce two worlds—the manifest world and the latent world. The manifest world is the world in which we exist and observe things, which the Buddha calls the world of “Name and Form”. It is the world of manifest phenomena around us and, in the formal analysis that follows, will be called M-space. There is no need to specify the mathematical structure of M-space, except to say that manifest phenomena we observe in the world of “Name and Form”, or the world of conventional reality, involve changes over time taking place in the three-dimensional space.

The world from which “Name and Form” are projected will be called the latent world—and L-space in the formal analysis below. It is the ground for all the manifest phenomena in the world around us. It is, in fact, the world of ultimate reality, the world of non-existence as the Buddha conceives it: “There is no material that exists for the production of Name and Form; and when Name and Form cease, they do not go anywhere in space. After Name and Form have ceased, they do not exist anywhere in the shape of heaped-up music material.” (Carus, P., The Gospel of Buddha, Oxford: Oneworld, 1994, p.114)

The Buddha’s view of the world is best represented by pratitya samutpada, or “dependent origination”, which expresses the idea that nothing in the world around us exists as an independent and separate entity. Everything exists, if at all, only in a relationship with other things linked by a network of causes and conditions. Things come into being as if from “nowhere” as a result of the concurrence of causes and conditions. From a formal point of view, we can express this idea as a mapping between L-space and M-space. To be more specific, we can define pratitya samutpada formally as:

(PS) ”xi exists in M” implies that “there exist F: L→M such that xi is an element of X in M”,

where F = (f1,f2,…,fm) and X = {x1,x2,…,xn}.

The formalism above says that something (xi) exists in the manifest world only because there exists some configuration of causes and conditions (f1,f2,…,fm) which brings into the manifest world some aggregate entity X = {x1,x2,…,xn} of which xi is a part. In general, we do not have direct access to a specific configuration of causes and conditions that gives rise to a specific aggregate entity. And the Buddha himself is relatively silent on the nature of the mapping that links the two worlds.

Systems science, too, is silent when it comes to the nature of the mapping that links L-space and M-space. What it does say is that things that exist in the manifest world exist as elements of a system, where a system is, according to Bertalanffy, “a set of elements standing in interrelations”. (Bertalanffy, Ludwig, General System Theory, New York: Braziller, 1968, p. 55) Formally, this can be expressed as: S = {X, R}, where X is a set of entities and R a binary relation defined on X, i.e., xiRxj, for all xi, xj in X. In negating the existence of separate and independent entities, there is indeed correspondence between the Buddha’s view of the world as represented by pratitya samutpada and a systems view of the world.

A whole, according to the idea of pratitya samutpada, is not a sum of identifiable, immutable constituent parts. Rather, a whole is defined only in the context of an aggregate of causes and conditions which gives rise to it. Both parts and whole come into being only as a result of the concurrence of causes and conditions. In this sense, nothing really exists as a distinct and separate entity, which is the idea of sunyata, or “emptiness”. What we perceive to be things around us, including ourselves, are actually composite entities which have no substance and which are constantly formed and destroyed: “All the elements of being, both corporeal and non-corporeal, come into existence after having previously been non-existent; and having come into existence pass away.” (Carus, op. cit., p. 40)

In the formal language of systems science presented above, pratitya samutpada implies sunyata because of the way (PS) is formulated. As a matter of fact, (PS) says two things: (i) xi does not exist by itself apart from X of which it is a part, and (ii) X does not come into being without F. These two aspects of sunyata can be stated formally as follows:

(SU-i) ”xi exists in M” if and only if “xi is an element of X”

(SU-ii) ”X is a non-empty set” if and only if “there exist F: L→M”

In the above reformulation of the idea of pratitya samutpada in the language of systems science, (SU-i) implies the principle of “interdependence between parts and whole”. As the Dalai Lama puts it: “Without parts, there can be no whole; without a whole, the concept of parts makes no sense.” (Ethics for the New Millenium, New York: Riverhead Books, 1999, p.37) On the other hand, (SU-ii) corresponds to the idea of sunyata as formulated by Nagarjuna: “Apart from the cause of form, form cannot be conceived. Apart from form, the cause of form is not seen.” (Garfield, J. L., The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, p.12)

What the formal statement (SU) says is that there are two complementary pictures to sunyata. Sunyata gives us a picture of the “parts-whole complementarity” among “things” as well as a picture of the “cause-form complementarity” that brings about “forms”. In fact, in suggesting “complementarity” between the parts-whole picture of reality and the cause-form picture of reality in the world around us, sunyata reminds us of Bohr’s complementarity principle in quantum mechanics. Hence, the formal statement of sunyata (SU) may be termed the “complementarity principle” in Buddhist thought.