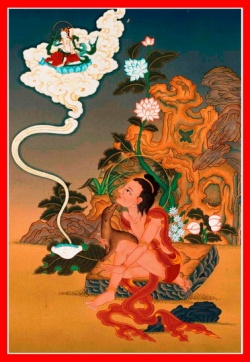

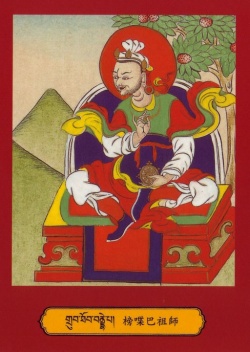

The 84 Maha Siddhas of Tibetan Buddhists

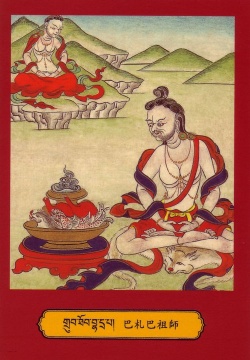

Some hold that there are 84 known Mahasiddhas in both Hindu and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, with some overlap between the two lists. Each Maha Siddha has come to be known for certain characteristics and teachings, which facilitates their pedagogical use. One of the most beloved Maha Siddhas is Virupa, who may be taken as the patron saint of the Sakyapa sect and instituted the Lamdré (Tibetan: lam 'bras) teachings. Virupa (alternate orthographies: Birwapa/Birupa) lived in 9th century India and was known for his great attainments.

Some of the methods and practices of the Maha Siddha were codified in Buddhist scriptures known as Tantras. Traditionally the ultimate source of these methods and practices is held to be the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, and often it is a trans-historical aspect of the Buddha or deity Vajradhara or Samantabhadra who reveals the Tantra in question directly to the Mahasiddha in a vision or whilst they dream or are in a trance. This form of the deity is known as a sambhogakaya manifestation. The sadhana of Dream Yoga as practiced in Dzogchen traditions such as the Kham, entered the Himalayan tantric tradition from the Mahasiddha, Ngagpa and Bonpo. Dream Yoga or "Milam" (T:rmi-lam; S:svapnadarśana), is one of the Six Yogas of Naropa.

Four of the 84 Maha Siddhas are women. They are Kanakhala, the younger of the two Headless (Severed-Headed) Sisters, Lakshmincara The Mad Princess, Manibhadra, the Model Wife (the Happy Housewife) and Mekhala (c. 900) the elder of the two Headless (Severed-Headed) Sisters. Von Schroeder (2006) states:

Some of the most important Tibetan Buddhist monuments to have survived the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976 are located at Gyantse in Tsang province of Central Tibet. For the study of Tibetan art, the temples of dPal ’khor chos sde, namely the dPal ’khor gTsug lag khang and dPal ’khor mchod rten, are for various reasons of great importance. The detailed information gained from the inscriptions with regard to the sculptors and painters summoned for the work testifies to the regional distribution of workshops in 15th-century Tsang. The sculptures and murals also document the extent to which a general consensus among the various traditions or schools had been achieved by the middle of that century. Of particular interest is the painted cycle of eighty-four mahåsiddhas, each with a name inscribed in Tibetan script. These paintings of mahasiddhas, or “great perfected ones endowed with supernatural faculties”, are located in the Lamdre chapel on the second floor of the dPal ’khor gTsug lag khang. Bearing in mind that these murals are the most splendid extant painted Tibetan representations of mahasiddhas, one wonders why they have never been published as a whole cycle. Several scholars have at times intended to study these paintings, but it seems that difficulties of identification were the primary obstacle to publication. Although the life-stories of many of the eighty-four mahasiddhas still remain unidentified, the quality of the works nevertheless warrants a publication of these great murals. There seems to be some confusion about the number of mahåsiddhas painted on the walls of the Lam ’bras lha khang. This is due to the fact that the inscription below the paintings mentions eighty siddhas, whereas actually eighty-four were originally represented.

List of the 84 Mahasiddhas

In Buddhism there are 84 Mahasiddhas (the asterisk * denotes a female):

Acinta or Acintapa, the 'Avaricious Hermit';

Ajogi or Ayogipa, the 'Rejected Wastrel';

Anangapa, Ananga, or Anangavajra;

Aryadeva (or Karnaripa), the 'Lotus-Born' or the 'One-Eyed';

Babhaha, the 'Free Lover';

Bhadrapa, the 'Snob' or the 'Exclusive Brahmin';

Bhandepa, the 'Envious God';

Bhiksanapa, 'Siddha Two-Teeth';

Bhusuku, Bhusukupada or Shantideva, the 'Lazy Monk' or the 'Idle Monk';

Camaripa, the 'Divine Cobbler';

Campaka or Campakapada, the 'Flower King';

Carbaripa or Carpati, 'Who Turned People to Stone' or 'the Petrifyer';

Catrapa, the 'Lucky Beggar';

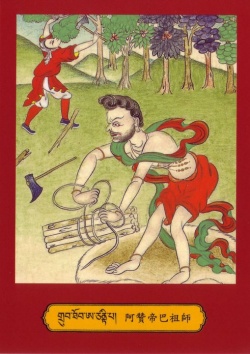

Caurangipa, the 'Limbless One' or 'the Dismembered Stepson';

Celukapa, the 'Revitalized Drone';

Darikapa, the 'Slave-King of the Temple Whore';

Dengipa, the 'Courtesan's Brahmin Slave';

Dhahulipa, the 'Blistered Rope-Maker';

Dharmapa, the 'Eternal Student' (c.900 CE);

Dhilipa, the 'Epicurean Merchant';

Dhobipa, the 'Wise Washerman';

Dhokaripa, the 'Bowl-Bearer';

Dombipa, the 'Tiger Rider';

Dukhandi, the 'Scavenger';

Ghantapa, the 'Celibate Monk' or the 'Celibate Bell-Ringer';

Gharbari or Gharbaripa, the Contrite Scholar (Skt., pandita);

Godhuripa, the 'Bird Catcher';

Goraksa, Gorakhnath or Goraksha, the 'Immortal Cowherd';

Indrabhuti, (teachings disseminated to Tilopa);

Jalandhara, the 'Dakini's Chosen One';

Jayananda, the 'Crow Master';

Jogipa, the 'Siddha-Pilgrim';

Kalapa, the 'Handsome Madman';

Kamparipa, [[the Blacksmith}}';

Kambala, the 'Yogin of the Black Blanket' (or the 'Black-Blanket-Clad Yogin');

Kanakhala*, the younger of the two Headless Sisters or Severed-Headed Sisters;

Kanhapa (or Krsnacarya), the 'Dark-Skinned One' (or the 'Dark Siddha');

Kankana, the 'Siddha-King';

Kankaripa, the 'Lovelorn Widower';

Kantalipa, the 'Rag Picker' (or the 'Ragman-Tailor');

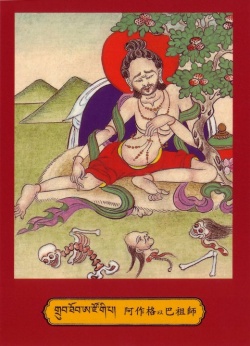

Kapalapa, the 'Skull Bearer';

Khadgapa, the 'Master Thief' (or the 'Fearless Thief');

Kilakilapa, the 'Exiled Loud-Mouth';

Kirapalapa (or Kilapa), the 'Repentant Conqueror';

Kokilipa, the 'Complacent Aesthete';

Kotalipa (or Tog tse pa, the 'Peasant Guru';

Kucipa, the 'Goitre-Necked Yogin';

Kukkuripa, (late 9th/10th Century), the 'Dog Lover';

Kumbharipa, 'the Potter';

Laksminkara*, 'The Mad Princess';

Lilapa, the 'Royal Hedonist';

Lucikapa, the 'Escapist';

Luipa, teachings disseminated to Tilopa;

Mahipa, the 'Greatest';

Manibhadra*, the 'Model Wife' or the 'Happy Housewife';

Medhini, the 'Tired Farmer';

Mekhala*, the elder of the two Headless Sisters or Severed-Headed Sisters;

Mekopa, the 'Wild-Eyed Guru' (or the 'Guru Dread-Stare');

Minapa, the 'Fisherman';

Nagabodhi, the 'Red-Horned Thief';

Nagarjuna, "Philosopher and Alchemist",

Nalinapa, the 'Self-Reliant Prince';

Nirgunapa, the 'Enlightened Moron';

Pacaripa, the 'Pastrycook';

Pankajapa, the 'Lotus-Born Brahmin';

Putalipa, the 'Mendicant Icon-Bearer';

Rahula, the 'Rejuvenated Dotard';

Saraha, the "Great Brahmin"

Sakara or Saroruha;

Samudra, the 'Pearl Diver';

Santipa (or Ratnakarasanti), the 'Academic' (the 'Complacent Missionary') was a teacher of Brogmi;

Sarvabhaksa, the 'Empty-Bellied Siddha' (or the 'Glutton');

Savaripa, the 'Hunter', held to have incarnated in Drukpa Künleg;

Syalipa, the 'Jackal Yogin';

Tantepa, the Gambler';

Tantipa or Tanti, the 'Senile Weaver';

Thaganapa,

Thaganapa, 'Master of the Lie' (or the 'Compulsive Liar');

Tilopa, the "Great Renunciate"

Udhilipa, the 'Flying Siddha' (the 'Bird-Man');

Upanaha, the 'Bootmaker';

Vinapa, the 'Music Lover', the 'Musician' (teachings disseminated to Indrabhuti) and Tilopa};

Virupa, inspired the Sakya lineage;

Vyalipa, the 'Courtesan's Alchemist'.

Identification of Mahasiddhas

According to Ulrich von Schroeder for the identification of Mahasiddhas inscribed with Tibetan names it is necessary to reconstruct the Indian names. This is a very difficult task because the Tibetans are very inconsistent with the transcription or translation of Indian personal names and therefore many different spellings do exist. When comparing the different Tibetan texts on mahasiddhas, we can see that the transcription or translation of the names of the Indian masters into the Tibetan language was inconsistent and confused. The most unsettling example is an illustrated Tibetan block print from Mongolia about the mahasiddhas, where the spellings in the text vary greatly from the captions of the xylographs. To quote a few examples: Kankaripa [Skt.] is named Kam ka li/Kangga la pa; Goraksa [Skt.]: Go ra kha/Gau raksi; Tilopa [Skt.]: Ti la blo ba/Ti lla pa; Dukhandi [Skt.]: Dha khan dhi pa/Dwa kanti; Dhobipa [Skt.]: Tom bhi pa/Dhu pi ra; Dengipa (CSP 31): Deng gi pa / Tinggi pa; Dhokaripa [Skt.]: Dho ka ra / Dhe ki ri pa; Carbaripa (Carpati) [Skt.]: Tsa ba ri pa/Tsa rwa ti pa; Sakara [Skt.]: Phu rtsas ga’/Ka ra pa; Putalipa [Skt.]: Pu ta la/Bu ta li, etc. In the same illustrated Tibetan text we find another inconsistency: the alternate use of transcription and translation. Examples are Nagarjuna [Skt.]: Na ga’i dzu na/Klu sgrub; Aryadeva (Karnaripa) [Skt.]: Ka na ri pa/’Phags pa lha; and Ghantapa [Skt.]:Ghanda pa/rDo rje dril bu pa, to name a few.

Concordance lists for the identifications of Mahasiddhas

For the identification of individual mahasiddhas the concordance lists published by Ulrich von Schroeder are useful tools for every scholar. The purpose of the concordance lists published in the appendices of his book is primarily for the reconstitution of the Indian names, regardless of whether they actually represent the same historical person or not. The index of his book contains more than 1000 different Tibetan spellings of mahasiddha names.

Other mahasiddhas

Tibetan masters of various lineages are often referred to as mahasiddhas. Among them are Marpa, the Tibetan translator who brought Buddhist texts to Tibet, and Milarepa. In Buddhist iconography, Milarepa is often represented with his right hand cupped against his ear, to listen to the needs of all beings. Another interpretation of the imagery is that the teacher is engaged in a secret yogic exercise (e.g. see Lukhang). (Note: Marpa and Milarepa are not mahasiddhas in the historical sense, meaning they are not 2 of the 84 traditional mahasiddhas. However, this says nothing about their realization.) Lawapa the progenitor of Dream Yoga sadhana was a mahasiddha.

References

Dowman, Keith (1984). The Eighty-four Mahasiddhas and the Path of Tantra. From the introduction to "Masters of Mahamudra", SUNY.

Dowman, Keith (1986). Masters of Mahamudra: Songs and Histories of the Eighty-four Buddhist Siddhas. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-88706-160-5

Reynolds, John Myrdhin (2007). The Mahasiddha Tradition In Tibet.

von Schroeder, Ulrich (2006). Empowered Masters: Tibetan Wall Paintings of Mahasiddhas at Gyantse. Chicago: Serindia Publications & Visual Dharma Publications Ltd.

White, David Gordon (1998). The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India. University Of Chicago Press.