The Heart-Essence of Buddhist Meditation

The common roots of various Buddhist meditative practices

Clinging to one’s school and condemning others

Is the certain way to waste one’s learning.

Since all dharma teachings are good,

Those who cling to sectarianism

Degrade Buddhism and sever

Themselves from liberation.

—Milarepa, The One Hundred Thousand Songs

During my initial private meeting with the Venerable Kalu Rinpoche, my first root guru, I asked him about the main points of meditation. He asked what kind of meditation I was doing, and I told him mindfulness of breathing. “What will you concentrate on when you stop breathing?” he asked.

That was a real eye-opener. Suddenly I realized that I might have to broaden the scope of my understanding of Buddhist practice. In time, I came to discover that it included a great deal more than any one meditation technique and also that the many forms of Buddhist meditation shared fundamental elements.

The philosopher Simone Weil characterized prayer as pure undivided attention. Here is where all contemplative practices have a common root, a vital heart that can be developed in an almost infinite variety of skillful directions, depending on purpose and perspective. Different techniques of meditation can be classified according to their focus. Some focus on the field of perception itself, and we call those methods mindfulness; others focus on a specific object, and we call those concentrative practices. There are also techniques that shift back and forth between the field and the object.

Meditation, simply defined, is a way of being aware. It is the happy marriage of doing and being. It lifts the fog of our ordinary lives to reveal what is hidden; it loosens the knot of self-centeredness and opens the heart; it moves us beyond mere concepts to allow for a direct experience of reality. Meditation embodies the way of awakening: both the path and its fruition. From one point of view, it is the means to awakening; from another, it is awakening itself.

Meditation masters teach us how to be precisely present and focused on this one breath, the only breath; this moment, the only moment. In the Dzogchen tradition we refer to a “fourth time,” the transcendent moment of nowness. In Tibetan this is called shicha, a transcendent yet immanent dimension of timeless being that vertically intersects each moment of horizontal linear time—past, present, and future. Whether we’re aware of it or not, we are quite naturally present to this moment—where else could we be? Meditation is simply a way of knowing this.

Different Buddhist schools recommend a variety of meditative postures. Some emphasize a still, formal posture, while others are less strict and more focused on internal movements of consciousness. Tibetan traditions, for instance, advise an upright spine, erect but relaxed; hands at rest in the lap, with the belly soft; shoulders relaxed, chin slightly tucked, and the gaze lowered with eyelids half shut; the jaw is slack with the tongue behind the upper teeth; the legs are crossed. A Soto Zen Buddhist saying instructs us to sit with formal body and informal mind. The common essential point is to remain balanced and alert, so as to pierce the veil of samsaric illusion.

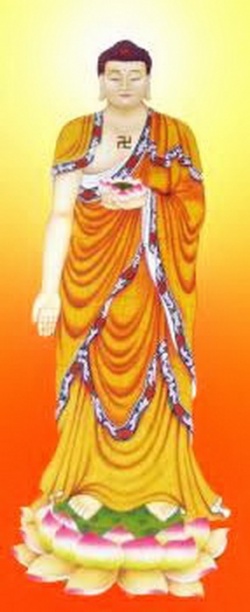

Although most Westerners tend to conceive of Eastern forms of meditation as something done cross-legged with eyes closed, in a quiet, unlit place, the Buddha points with equal emphasis to four postures in which to meditate: sitting, standing, walking, and lying down. The Satipatthana Sutra says: “When you sit, know that you are sitting; when standing, know you are standing. . . .” This pretty much covers all our activities, allowing us to integrate meditative practice into daily life. Learn to sit like a Buddha, stand like a Buddha, walk like a Buddha. Be a Buddha; this is the main point of Buddhist practice.

While many people today practice meditation for physical and mental health, a deeper approach to practice energizes our inner life and opens the door to realization. In Tibetan, the word for meditation is gom, which literally means “familiarization” or “getting used to,” and in this sense meditation is a means by which we familiarize ourselves with our mind. The common Pali term for meditation is bhavana, meaning “to cultivate, to develop, to bring into being.” So we might then think of meditation as the active cultivation of mind leading to clear awareness, tranquility, and wisdom. This requires conscious effort.

But from another—and at first glance contradictory—perspective, there is nothing to do in meditation but enjoy the view: the magical, mysterious, and lawful unfolding of all that is, all of which is perfect as it is. In other words, we’re perfect as we are, and yet there’s work to be done. In this we find the union of being and doing: we swoop down with the bigger picture in mind—the view of absolute reality—and at the same time we climb the spiritual mountain in keeping with our specific aspirations and inclinations, living out relative truth. “While my view is as high as the sky, my actions regarding cause and effect (karma) are as meticulous as finely ground barley flour,” sang the Lotus Master Padmasambhava, who first brought Buddhism to Tibet in the eighth century. By alternating between active cultivation and effortless awareness, we engage in a delicate dance that balances disciplined intention with simply being. By being both directive and allowing, we gradually learn to fearlessly explore the frontiers and depths of doing and being, and come to realize that whatever is taking place, whatever we may feel and experience, is intimately connected with and inseparable from intrinsic awareness.