The Lazy Path to Enlightenment

Episode Description:

We’re joined this week by author, teacher, and Tibetologist Glenn Mullin. During our conversation with Glenn we focus primarily on a system of teachings in the Tantric tradition called The Six Yogas of Naropa. He speaks about each aspect of the practice—including such practices as sexual yoga, dream yoga, and bardo yoga—and also explains why he thinks the 6 yogas are a perfect compliment for the modern lifestyle.

Transcript:

Vincent: Hello, Buddhist Geeks. This is Vincent Horn, and I’m joined today in Asheville, North Carolina with Glenn Mullen. Glenn, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with the geeks. We really appreciate it.

Glenn: It’s geek heaven.

Vincent: It is geek heaven here. For sure.

Glenn: My joy and my pleasure.

Vincent: Thank you. And just a little bit of background information, then we’ll kind of get deeper into it as we explore some of the things that we’re here to talk about. You’re a Buddhist art curator, Tibetologist, meditation teacher, author of tons and tons of books on all kinds of cool stuff, including the history of the Dalai Lama lineage, Buddhist art, the Six Yogas of Naropa, and I’m sure I’m leaving out several other topics. So, prolific Buddhist teacher and thinker, and it’s great to have you here.

Glenn: More. Go on, go on.

Vincent: [laughs]

Glenn: There’s so much more to say.

Vincent: There’s so many more books to talk about!

Glenn: No, it’s very kind of you to have me on your show, and thank you very much for that.

Myself, I was born in 1949, the year that China announced they were going to invade Tibet. And they followed that through the following year, 1950, and in 1951 conquered Tibet, and basically have occupied it since that time. That led to the total upheaval of Central Asia, an area larger than the United States–everywhere from Ladak, Lahaul Spiti in the Indian Himalayas to Siberia in Eastern Russia.

That was the tragic side of that era. The positive side, of course, is that it threw several thousand very great spiritual masters out of the Himalayas and onto foreign soil. Amongst those, Geshe Wangyal landed in America, and I think a Trungpa Tulku landed in England, and Dorzong Rinpoche landed out in Seattle, and of course the Dalai Lama, the great jewel of that whole tradition, landed in India, and from that time has become one of the great treasures of humanity, I think. He comes to America now almost every year, and has really transformed the way people around the world think of each other. So on the tragic side, it’s the loss of a great civilization, or at least the temporary stunning of a great civilization, and on the other hand, it is the beginning of a most wonderful cross-fertilization.

I mentioned that, 1949, because I was born at the very beginning of that phase of our history, and it has been very exciting for me, over the last 40 years or so, to basically watch the Tibetans go from being a very little-known peoples on this planet to having the Dalai Lama as a Congressional Gold Medal of Honor person, a Nobel laureate, and so on and so forth. Just yesterday I was looking on the web and I think another Tibetan Lama from Bhutan just got another UN award for his humanitarian work. So they’ve gone from being this obscure little sort of–how were they in “Star Wars,” the sort of teddy bears up in the mountains? [laughter] To being really central players on the main stage of world civilization today.

Vincent: And how did you get into Tibetan Buddhist practice? At some point did you meet a certain teacher that kind of did it for you, or how did you find your way to this very interesting path that most Westerners at that time weren’t even aware of?

Glenn: I started with the literature as a teenager. My mom was from England, and the Brits were always strong on Asia. Her dad had been a Major in the army in India, although she herself never lived in India, but it made India and Asia a part of the household linguistic. So, as a teenager I started reading some of the Asian classics—the Tao Te Ching, and Sufi literature, the Bhagavad Gita, the Upanishads, and so on and so forth.

I think my first Tibetan book I encountered was a Bardo Thodol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the old 1927 translation by Kazi Samdup, edited by Evans-Wentz. And when I read it I just knew that’s where my heart lay. That’s where my spiritual instincts, my philosophical leanings, my shamanistic tendencies–somewhere between life and death there lies the deepest truth of being–that kind of sense that came out of that book for me.

Vincent: And did you end up studying with a particular teacher or lineage, or how did you end up finding your way into the heart of it?

Glenn: After reading for some years–actually, my university over here was a science university, engineering, so it had nothing to do with Asian studies. It was completely a passion and a hobby. But after school I went to England for a year and then from there to India and the Dalai Lama had just opened a school for Western people in 1971, so I arrived in 1972 and met with the Dalai Lama. And well, yes certainly the man knocked my socks off there’s no question. He was every bit of dynamic as a young man he is as a sort of aged Sage.

I started studying in that school remained in it for about 6 years. The timing was very good. At that time many of the old masters from Tibet were still alive and they are 60s, 70s, 80s, some of them in their 90s. Of course it was also a sad time, because every year 2 or 3 of them would pass and it would be the passing of a whole millennium of knowledge really that those individuals held. I studied there for about 12 years continuously and then for another 6 years I’d go for 6 months a year to continue my studies, do retreats and so far, so in that way it went on for about 18 years.

Vincent: You mentioned to talking a little bit about your history that you have shamanistic tendencies, and I was kind of curious what did you mean by that?

Glenn: Well, the word shaman is originally a Tibeto-Mongolian word, we just adopt it in the West and apply it to other cultures. To me it has deep respect for ancestors and ancestral spirits. That for me to become a great being I have to absorb every greatness of all my forefathers and every greatness of all my foremothers and bring them together within myself. I have to be able to hear the whispers of their voices and to respond to those, to fulfill those wishes and prayers. So on the one hand, in a kind of internal way, it has that kind of meaning.

In another sense the trees talk to us, the wind talks to us, clouds talk to us, the earth and the sky are always talking to us. It’s not like we are a little separate entity, like a bug on a boulder seems to look separate from the boulder. The reality is that we are completely a fabric of the rest of the universe. When I breathe in air, it comes from China so I can’t be anti-China. When I eat a tomato, the water that fell on it probably came across the ocean from Africa and so forth. I hold up my hand and sunlight and starlight from far away celestial bodies come into me and I am part of all those things.

I think the shamanic tradition from ancient times has honored that integral part, there’s nothing separate about us. I can dream here and you can on the other side of the planet and our dreams can blend and fuse and create great transformations. So I think the shamanic tendency is the tendency to listen to nature, to listen to ancestors, to realize we’re part of the most ancient history and also we are going to go into the future as part of the most far-away futuristic history.

As the expression goes, when a butterfly flaps its wings in Nebraska; the saying doesn’t exactly go in Nebraska but I like Nebraska. I thought if I don’t mention it with the butterfly, it will never get into the conversation and those Nebraskins will be feel left out. [laughter] Then people from far away Tasmania feel some sort of cooling breeze on their backs. I think there is that element to central Asian spirituality, which is so deeply rooted in shamanism. The idea that it’s not us against the universe or us separate from the universe that’s really that, my every breath is the universe.

Vincent: Thank You. And I am guessing connected with this I know one of the types of teaching that you do is on the Six Yogas of Naropa, we’ve never explored that on the show I don’t think, so I was wondering if you could say little bit about that particular type of teaching and what it’s about?

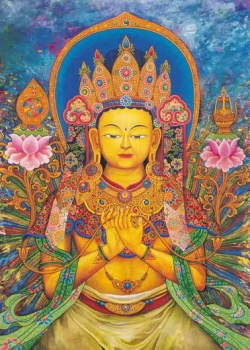

Glenn: [[Wikipedia:Central Asian|Central Asian]] but in some general is a fusion of what’s called the sutra teachings of the Buddha, or the general public teachings, which means things like love and compassion and patience and meditation and so on, and the tantric tradition. So the Six Yogas of Naropa are the tantra side of things. All Tibetan schools regard the sutra side as the basis and the foundations, and the tantra as the kind of crown jewel, the kind of the pinnacle of the practice, the pinnacle of the training.

I took a deep interest in the Six Yogas I think because firstly many of the masters whom I met had engaged in it and gotten great realizations through it without having to go through great hardships. And sometimes in the West we think of enlightenment as something hard to get and very far away. So the ease of application of the Six Yogas is something that was very… I mean I am naturally a very lazy guy by predisposition. So if someone says, “well we can look for a hard way to our enlightenment or an easy way to enlightenment” I kind of like the easy way idea. So the Six Yogas are said to be like that. They take the five main tantra systems taught by the Buddha and they strip their quintessential elements and put them forth in a very clearly accessible manner.

The hard side of them of course is that a lot of what’s there is in the oral tradition.

And so like they say, “lamas are like drums, you have to beat them to get the sound.” So then you have to hand around those guys quite a while to get them to actually open up some of those meanings and practices. But, if you are like me, a little on the lazy side and patient then eventually it happens.

So if we look at the Six Yogas… It’s really a kind of a crib word for a very large tradition and a very wide-spread tradition, I think one of the most popular practice traditions in Tibet. Philosophically is not that dazzling as some of the other tantra systems schools, Guhyasamaja or the shitro tradition from the Nyingma or so on. But in the terms of the purity of practice, and the transformative power of direct practice it’s one of the great Tibetan lineages.

I think one of the reasons is that it combines both physical application and mental / spiritual application in a very direct way. So a lot of the other practices from Tibet tend to be a little more on the physical side or a little bit more on the mentalistic side.

In general if we make it six, and the Tibetans have two ways, but one is to make the foundation of the practice, the control of the subtle mind and subtle energies of the body. Sometimes this is termed the fierce fire or the inner fire practice. Similar to some parts of the tantric tradition that the Buddhists share with the other traditions of India with the chakras, and the nadis, and the power of breathing, and sense withdrawal, and so forth. similar somehow to some elements of the Patanjali yoga system.

So that is the basis. Then as the real body of the practice, on the energy side being able to cut the breath for extended periods of time and separate mind from body, so that to all extensive purposes your body may look dead, or stop breathing, or heart seems to stop the beating and so on. As one of my lamas put it, you have to get your oxygen through your ears for the next hours or days. [Laughs] It’s called the illusory body practice because the energies, which are the foundation of existence, the energies which are the supports of the soul you could say, are brought into their finest form. And it’s just those energies, which support your spirit, or your soul. And the body itself is put into a kind of deep sleep. And that’s on the energy side.

On the mind side then giving rise to the primordial, as Christians would say Christos, giving rise to the deepest level of consciousness, and just resting in that deepest level, without thoughts of this century or that century, this millennium or that millennium, this universe or that universe. Just resting in touch with your own primordial nature, the quality of conscious being which is the same today as it was in a human being a million years ago or it will be in a living being a million years from now–that primordial or universal mind. So those are the two main aspects of practice. What makes it unique is the using of the fire to create this practice environment.

Sometimes an extra is thrown in, which is sexual yoga, or passion yoga, because sexuality is our deepest human instinct. Probably our second is killing or destruction, so sex and death, and that’s why, of course, in America, Hollywood formulas are often sex and death, sex and death, sex and violence. They’re very primordial aspects of the human psyche and of the human instinct, and so, tapping in to those primordial qualities, doesn’t mean, necessarily, being sexually indulgent or going out and killing the neighbor’s dog…

Vincent: [laughs]

Glenn: …but tapping in to that primordial urge or that primordial instinct, and then using those two primordial instincts as kind of the two sticks that you rub together to give rise to the fire or the flame of the enlightenment experience.

Those three are the basis of the practice. They throw three on top of them as kind of supporting practices. One’s called Phowa, which means opening the death canal. So, in meditation, you do a forceful energy chakra-nadi practice until you create a blister on the top of your head, so that if you die before you achieve enlightenment, you’ll pop out the right place. [Laughs] Tibetans and the Indians have that very strong sense that when consciousness leaves the body, if it has already prepared that passage, then death becomes much more transformative in a positive way.

Dream yoga, being able to stay awake in your sleep, and be fully conscious in your sleep, and do particular kind of yogic applications in your dreams, using your dreams for spiritually-transformative purposes. On a higher level, when you get really good at the dream yoga, then you can become like a kind of a Superman or a Spider-Man in your dreams and run around the planet, fixing bridges and filling in potholes in New York City and stuff like that. [laughter]

The idea is, in our dream state, we’re always doing stuff, and that’s all energy, and it’s either helping us or harming us in terms of us as a human being. It helps our health or it harms our health. It helps our happiness or it harms our happiness. It helps the world around us because we’re exuding it, or it harms the world around us because we’re exuding it. So, if we can learn to sleep and dream on a higher plane, then even when we’re asleep, we’re always being beneficial, both to self and others. So, dream yoga is considered one of the great accelerators of enlightenment in the tantric tradition. It’s said that a person who accomplishes dream yoga–that one day becomes like a hundred years for someone who hasn’t accomplished it. Because without it, then our body is never fully rested. We go to sleep, we toss and turn, and the body never achieves full healing and rejuvenation, so we become a mere fraction of our potential greatness.

So there’s a strong emphasis on that yoga. And another one is Bardo yoga. Training in out-of-body experience. How to leave the body, experience death in your meditation. And again the Tantric tradition thinks this is something quite easily accomplished, but very beneficial when accomplished. You hear people walking around arguing is reincarnation true, is it not true, blah blah blah blah? Who cares if you can’t directly experience yourself? No amount of talking brings any benefit. It’s like saying, “Are the peaches more yellow on the south side of China or the north side of China,” if you’ve never visited China. But, the Tantric tradition is in your meditation you can directly experience after death, merely by a couple of breathing exercises followed by a few slightly sneeze-sounding mantras. [Laughs] And again because it’s a deeper level of consciousness it brings great transformation.

Many people in Tibet they used to say, “the Six Yogas of Naropa is the lazy man’s enlightenment because you can get it in sleep and you can get it sitting in meditation with your consciousness out of your body.” And what’s more easy than just sitting in meditation with your consciousness out of your body? I mean, your body is just sitting there, it’s totally easy. Your mind is just kind of wandering around blown on the winds of your own imagination.

The other interesting thing about it is that it really incorporates everything in life. Some practices there’s things we should eat, or there’s things we can’t eat, and there’s things we can do and things we can’t do. It’s sometimes called the path of no accepting and no rejecting. In other words don’t look for anything other than what’s there and don’t be upset by anything which is there. Just take whatever is present in the moment as the pure amrit or the pure delicious, joyful, nectars of ecstasy. So, it makes an ideal practice for the modern world I think where it’s very easy to get irritated at having too much of this or not enough of that. Rush-hour traffic, perhaps someone practicing the trombone in the apartment next to you at 3 in the morning, and so on and so forth. Or just at work, a lot of challenges that people experience at work. The beauty and strength of the Six Yogas is that whatever arises is always the perfect situation for you at that time.