The Mahasiddhas

Throughout Buddhist history people have revered the Buddha and the community of monks and nuns who uphold his teachings. The Buddhist sangha has served as a living lineage, preserving the teachings of the Buddha in both scriptural transmission and realization. A lesser known but equally important role in the transmission and realization of the Buddha's teachings fell on the mahasiddhas.

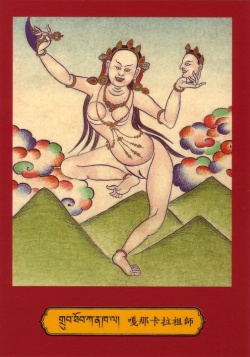

A mahasiddha is a tantric practitioner who embodies the state of perfection. Mahasiddha means 'great accomplishment', a yogin who has brought his sadhana or practice to its completion and achieved realization. The mahasiddhas played a key role in the preservation and development of the Buddha's teachings in India and Tibet, as displayed in the songs of realization of the Lives of the 84 Mahasiddhas.

Adapted from Dowman and wikipedia:

The mahasiddhas represent remarkable diversity in their family backgrounds and social roles. Indeed they could be found in every social setting: kings and priests, poets and musicians, craftsman and farmers, housewives and whores. They were artists and businessman, respected doctors and neglected beggars, politicians and hermits.

The Mahasiddhas were a diverse group of practitioners who were practical, committed, creative and engaged with their world. As a collective, their spirituality may be viewed as key and essential to their lives- simple, in concert and accord with all aspects of their lived experience. The basic elements of the lives of the Mahasiddas included their diet, physical posture, career, relationships; indeed "ordinary" life and lived experience were held as the principal foundation and fodder for realization. As siddhas, their main emphasis in spirituality and spiritual discipline was a direct experience of the sacred and spiritual pragmatism.

The mahasiddha tradition may be conceived and considered as a cohesive body due to their spiritual style, sahaja or naturally born- which was distinctively non-sectarian, non-elitist, non-dual, non-elaborate, non-sexist, non-institutional, unconventional, unorthodox and non-renunciate. The mahasiddha tradition arose in dialogue with the dominant religious practices and institutions of the time which often foregrounded practices and disciplines that were over-ritualized, politicized, exoticized, excluded women and whose lived meaning and application were largely inaccessible and opaque to non-monastic peoples.

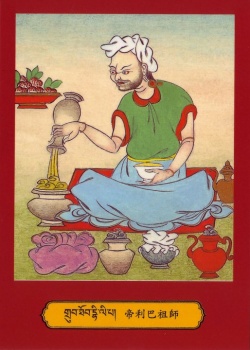

The practice of the mahasiddha was often depicted as taking place in a charnel ground. This charnel ground is not merely the physical cremation ground; it can also be discovered or revealed in completely terrifying mundane environments where practitioners find themselves desperate and depressed, where conventional worldly aspirations have become devastated by grim reality. This is demonstrated in the sacred biographies of the great siddhas of the Vajrayāna tradition. Tilopa attained realization as a grinder of sesame seeds and a procurer for a prominent prostitute. Sarvabhakṣa was an extremely obese glutton, Gorakṣa was a cowherd in remote climes, Taṅtepa was addicted to gambling, and Kumbharipa was a destitute potter. These circumstances were charnel grounds because they were despised in Indian society and the siddhas were viewed as failures, marginal and defiled.

- * * * * * * * *

We can find a lot of inspiration and blessings in the lives of these mahasiddhas. They rejected the notion that liberation was only for a chosen few, that your circumstances restricted your practice. They lived just the opposite, your life was your practice. The entirety of your lived experience was the basis for your realization.

But mostly they showed that it was possible. Whatever your situation, lifestyle or profession; liberation was in the palm of your hand.