The Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism

The Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism

by Martin Brauen

- The mandala is fundamentally something secret. If you are interested in it in order to acquire reputation, and feel pride in showing what you have worked out to others, you do not have the right attitude. If however your work springs from efforts to offer help to other people, that is the right attitude of mind, which will contribute to the liberation of yourself and others.

- Khenpo Thubten to the author

This article offers an introduction to the mandala as used by Tibetan Buddhists, and gives a critical perspective on the eminent psychologist C.G. Jung’s interpretation of the sacred icon. Both are the topics of exhibitions shown at the Rubin Museum of Art (RMA): Mandala: The Perfect Circle (August 14, 2009 – January 11, 2010) and The Red Book of C.G. Jung: Creation of a New Cosmology (October 7, 2009 – January 25, 2010).

RMA holds one of the world’s most important collections of Himalayan art. Paintings, pictorial textiles, and sculpture are drawn from cultures that touch upon the arc of mountains that extends from Afghanistan in the northwest to Myanmar (Burma) in the southeast and includes Tibet, Nepal, Mongolia, and Bhutan. The larger Himalayan cultural sphere, determined by significant cultural exchange over millennia, includes Iran, India, China, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. This rich cultural legacy, largely unfamiliar to Western viewers, offers an uncommon opportunity for visual adventure and aesthetic discovery.

Tibetan Buddhism relies on the visual with an intensity that far exceeds other forms of the religion. Understanding the absolute nature of reality to be devoid of all characteristics and yet fully manifest in everyone and everything, Tibetan Buddhist practitioners engage in special practices in order to realize the pure in what was previously viewed as impure, realizing buddhas where before they knew only of ordinary beings. Vastly complex pictorial representations of the Buddhist conception of the world and its deities serve as aids to the meditator. Figures of deities – be they painted on walls or cloth or fashioned out of metal, wood, or clay – are endowed through consecration to stand in for the deities they represent, enabling the practitioner to properly visualize the reality he or she strives to embody.

The concept of the mandala is extremely complex, and it is hard to do justice to the word with only a brief definition. In dictionaries mandalas are described variously as magic circles, round ritual geometric or symbolic diagrams, or, typically, circles that surround a square with a central symbol. Alternatively, mandalas are explained as symbols of the cosmic elements, as models for certain visualizations, as aids to self-discovery, or as aids to meditation on the transcendental. All these definitions are correct as far as they go but are not nearly precise enough.

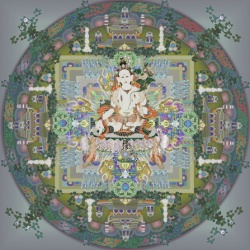

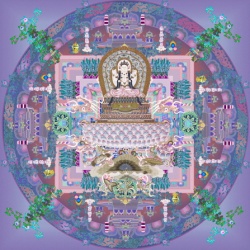

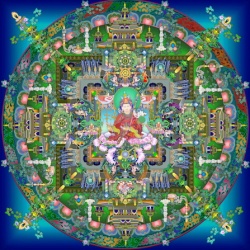

As a rule a mandala (dkyil-’khor) is a strongly symmetrical diagram concentrated about a center; it is built up of concentric circles (’khor) and, in most cases, squares possessing the same center (dkyil). Almost all mandalas familiar today display one or more concentric circles in the center. The basic construction varies only slightly. About a round, central disk, in the middle of which there sits or stands a deity, four, eight, or ten deities are set in an additional circle. These figures are the assembly or entourage of the most important deity of the mandala.

Among the plethora of mandala representations, there are a number in which the deities are only hinted at, for instance by their symbols, by their seed syllables, or by dots or small circles. Some mandalas may be completely empty, and these naturally demand greater powers of imagination. Two-dimensional mandalas are either painted on a cloth ground or on a flat surface by sprinkling colored powders. Whereas the latter types are dismantled at the end of the relevant mandala ritual, painted mandalas can be stored away for future use.

The palace and its central area

In the great majority of mandalas known to us, the innermost sacral area is surrounded by a square. Each of the four outer sides of the square is interrupted in the middle by a T-shape. These represent entrance gates, since the square in the mandala is none other than a building or the ground plan of a palace.

Generally the walls of the palace are adorned with strings of pearls and the roofs with umbrellas, banners, vases, pennants or other objects. However, in a few mandalas entrails hang on the walls. These are mandalas of certain wrathful deities, whose palace roofs are sometimes adorned with swords, yaktail fans, and impaled corpses — in place of umbrellas, banners, and so on. An example of such a mandala is that of Black-cloaked Mahākāla.

As a rule, the square palace area rests on a crossed vajra (viśvavajra), which forms the adamantine foundation of the mandala palace. The four points match the colors of the corresponding cardinal directions. The crossed vajra is particularly visible in three-dimensional mandalas.

The concluding protective circles

In Tibetan mandalas familiar to us today, the square palace is encompassed by three or four circles. There is reason to assume that in very early mandalas outer circles were absent, and there were only concentric circles inside a square domain. Outer circles were probably not added until the eleventh or twelfth century.

The three circles or rings that usually complete a mandala on the outside are, from the inside outward, the lotus flower, the vajra, and flame circles. The lotus flower circle represents a large lotus flower that serves as a support for the mandala (the palace and its divine occupants). The blue circle with vajras marked along it points out that the entire sacred realm of the mandala is separated, and thereby protected, from the surrounding world by what can be described as a kind of adamantine cap, bell, or “vajra-cage.” And, as if this protection were still not enough, around every mandala a circular fire blazes to keep all negative forces far away from the inside of the mandala.

In a relatively large number of mandalas a fourth circle in which the eight charnel grounds are depicted, is added to the first three. Each charnel ground contains the same basic elements: a mahāsiddha (yogin), ākinī, protective deity, stūpa, tree, cloud, forest, hermit, ocean, mountain, and naga. Such representations of charnel grounds remind the person meditating of the transitoriness of all existence. For is there any place more suitable than a charnel ground to meditate on the fleeting nature of existence? That in early mandalas these charnel ground scenes were not depicted in a separate circle but in the whole area outside the mandala is indicated by a Cakrasamvara Mandala ascribed to the twelfth century, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Other mandalas

Numerous scroll paintings depict mandalas that are not recognizable as such at first sight. The characteristic type of mandala in such paintings becomes clear when the paintings are analyzed, and the mandalas are thereby revealed as three-dimensional, symmetrical structures, concentrated about a center.

Even the individual deity can appear as a mandala: thus Kālacakra dominates the mandala of the same name. Like his partner Viśvamātr he has four faces, each looking toward one of the four cardinal directions. His arms, together with those of his partner, describe a circle about an (imagined) center at the level of the heart.

Eventually, in the context of the picture of the person in the Kālacakra Tantra, we shall find out that the human being, too, is seen as a mandala. For instance, each of the wind channels, which according to tantric conception flow inside the body, is linked to a particular direction, element, aggregate (skandha), and color, thereby forming a mandala. According to the a Sutra text (Dharmamandala Sūtra), the human body is regarded as a type of fivefold mandala represented symbolically by the trunk and the four limbs.

Three-dimensional mandalas

Since the beginning of the 1990s, a new generation of three-dimensional mandalas has been created with the help of computer programs. At the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich, I have created the first computer animation of a three-dimensional Kālacakra Mandala and of the Kālacakra cosmos. Since then, more computer-animated mandalas have been produced: Recently Kavita Bala from Cornell University and her team have made a computer-animated Kālacakra Mandala, which is – thanks to newer technology - far better than the one made many years ago at the University of Zurich. (To view this computer-animated mandala, go to http://www.cs.cornell.edu/~kb/mandala/ This is offered with permission from Kavita Bala.)

The advantage of this new technology is that in computer-generated threedimensional mandalas certain details and features can be shown better than in pictures or in three-dimensional models of wood or metal: transparency and luminescence. The new technology also allows a mandala palace to be entered and explored, not just in the imagination but virtually.

Abandonment of self

Despite their partly divergent views and rituals, the different Buddhist schools and traditions of teaching share certain basic assumptions, in particular the theory of selflessness. What we in the West consider to be an individual, in the Buddhist view comprises five so-called aggregates or heaps (skandha). These are the skandhas of forms (corporeality, materiality, matter), of feelings, of perceptions, of mental factors (volition, mental formations), and

of consciousnesses (events of consciousness), which combine with each other in mutual interrelation. The five skandhas are transitory and subject to constant change, thereby also implying the transitory nature of human beings. That which is transitory can, moreover, possess no eternal soul or — as Buddhists also say — no permanent self. In the West the individual is thought to

possess a content, a core, which for Buddhists is a wrong view, the root of all our misery. The concept of “I” and of “self” leads to craving, which continually gives rise to new dissatisfaction, anguish, and sorrow. As a consequence of this realization, the delusion of self has to be abandoned. If a person escapes from the shackles of the self, he or she escapes also from craving and with it from sorrow and comes closer to the state known as nirvāna, which for Buddhists means freedom from bonds, freedom from attachments, freedom from craving. This state of freedom and independence permits an active life and a feeling of closeness to others to arise - giving up the self makes sense only if it goes along with a turning toward other living beings.

All Buddhist schools agree on the ideal of selflessness. Differences exist in the method, the way (yāna) in which the experience of non-essence can be attained. To simplify greatly, one can distinguish between the two ways: the Sūtra- or Pāramitā-yāna (Way of the Perfections) and the Tantra- or Mantrayāna (Way of Sacred Formulas). The system of the Sūtras relies on texts that

emphasize instruction and time-consuming intellectual analysis of oneself and one’s surroundings, and the system of the Tantras is based on texts that explain how with demanding, partly secret, ritual practices, above all with deity yoga, one can rapidly, though with greater risk, realize the ultimate goal of essencelessness, or emptiness.

Emptiness: all phenomena are “of the same taste”

Tibetan Buddhists regard what is generally called reality as being without essence, without a stable core or — to use a Buddhist expression — as empty. Out of the wrong interpretation of perceptions and human longings arise contradictions, which the Buddhist wants to recognize with the aid of meditation. The meditator grasps that his or her reality is not real, that another reality exists instead: emptiness, or the void (Śunyatā).

But how can emptiness be reality? Emptiness is a central, exceedingly complex concept of Mahāyāna philosophy. From among the various concepts of emptiness, we will draw on the widely held concept of the Prāsangikamādhyamika School. This school regards phenomena and beings as empty, in so far as they have no inherent or objective existence of their own, that is, no existence inherent in the object. It is not a matter of the complete non-existence of a phenomenon but of the lack of a Self. The Prāsangika concept does not put in question the world of things and people around us but rather the way we see the world.

One example may be used to illustrate the theory of emptiness.

It is provided by the well-known puzzle pictures in which blotches, lines and dots yield next to no meaning and cannot be interpreted. After looking and searching for a long time, you suddenly recognize some content, for example a face or a shape. But the blotches, lines, and dots of the first phase — of nonrecognition — are exactly the same as those of the second phase — that of recognition of content. Nothing has altered; evidently it is the viewer who has changed. With his consciousness he has analyzed, distinguished, and organized the dots, lines, and blotches. He has made discriminations and bestowed content and meaning on that which is empty.

(This demonstrates not only how with our discriminating, analyzing consciousness we create independent entities from that which is empty but also how hard it is to return these entities to the undifferentiated state. Who does not know the difficulty of dissolving a puzzle picture back into mere dots, lines, and blotches once one has made out its hidden content? Order cannot be led back into disorder, or only with great effort. But this is precisely what someone meditating on emptiness must succeed in doing, because reversing the process of ordering, differentiating, and constituting (seeming) entities means recognizing the emptiness of all appearances.)

Contrary to the view, widely held in the West, of the tantric practitioner as disregarding all conventions without restraint, the person who has opted for the tantric way must, like other Buddhists, observe numerous ethical rules. These include the basic Buddhist rules not to kill, lie, steal, commit adultery, or take intoxicating drink.

The practitioner encounters one particular ethical precept again and again: the demand to cultivate the so-called Mind of Enlightenment (Bodhicitta; byang-chub-kyi sems), the altruistic mind of realization of emptiness that is guided by the wish to attain complete and perfect enlightenment for the benefit of others. “Selfless” means on the one hand without self, or without any self, and on the other being unselfish, willing to make sacrifices, altruistic and devoted to others, and thereby implies a demand for social action. The ultimate goal is not one’s own liberation from the cycle of suffering but the liberation — and so happiness — of all living beings.

Drawing the mandala lines

Mandalas cannot be drawn and painted freehand but are based — like all Tibetan religious statues or paintings — on a basic grid of lines. When this has been done, the preparation of the deities follows: a monk purifies their seats with saffron water, and the vajra-master sets down a grain of barley on the relevant place for each deity and recites a mantra for each. In this way the monks generate the entire mandala and the deities within it. The actual construction of the mandala follows as the last phase of ritual preparation. At this point the coloring of the mandala begins. The colors and shapes are precisely stipulated. As a visual aid, the monks in charge use handbooks that depict the most important figures and ornaments.

After completion of the mandala and after particular vows have been made, the candidate, dressed as a deity, is ready to enter the mandala in visualization. As he is blindfolded at first, the vajra-master leads him like a small child. Next follow two prognostic actions whose outcome tells the vajra-master how he should lead the disciple into the mandala.

When these preparations are concluded, the candidate can finally take off the blindfold and behold the entire mandala in all its splendor. The initiations purify the disciple systematically and gradually so that he eventually becomes a suitable vessel for Tantric practice. Because of that the principal deity and other deities empower him to practice different meditations, which all help him to experience the inherent mind of clear light and at the same time to open him to the sorrows of all living beings. The initiations are consequently steps on the path to buddhahood.

During the generation stage, the practitioner ripens and prepares his stream of consciousness for the completion stage, which leads to the attainment of perfect buddhahood in the form of Kālacakra and his partner. This stage too involves demanding visualizations, which can only be properly understood and carried out under the guidance of a spiritual teacher. Once buddhahood is attained, aids such as

depictions of deities, ritual objects, and indeed the mandala itself are no longer necessary. They can be destroyed. In the case of the Kālacakra Mandala, the colored powder from which it was sprinkled is wiped together carefully and poured into a river, where it forms one final mandala — when the powder trickling into the water makes concentric circles, which soon vanish in the infinity of water droplets.

Symbol of unity and divinity

Attempts have been made to establish the original source of the mandala and its spread over great distances from a clearly defined region of origin but so far they have not been convincing.

In this connection one contribution of Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) is the fruitful hypothesis that the circle and the quaternity are symbols deeply rooted in the human soul that can emerge in different places without implying any direct diffusion. Jung showed himself to be very open-minded toward Eastern teachings of wisdom, and we have at least to thank him for the fact that the word mandala is not entirely unknown in the West.

In spite of the valuable basic approach and the important introduction of the mandala into the European world of thought, a certain caution is called for as to Jung’s attempt to interpret individual elements of Tibetan mandalas. For example, he interpreted the outermost fire circle of the mandala—for him it was apparently synonymous with a yantra—as ‘‘the fire of desire, from which proceed the torments of hell.’’ He called the mandala palace a monastery courtyard; equated it without further ado with the

concept of yin and yang, which comes from the Chinese world of thought; and even spoke of Tibetan Buddhist mandalas in relation to emanations of the Hindu god Śiva. We should not forget that Jung’s knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism was strictly limited, in part because of the dearth of reliable publications and studies at the time, which led almost inevitably to these misunderstandings and misinterpretations.

Jung nevertheless grasped intuitively a great deal of the deeper meaning of the mandala ritual, as a few lines from his unfortunate interpretation of a Tibetan mandala show:

- The goal of contemplating the processes depicted in the mandala

- is that the yogi shall become inwardly aware of the deity;[ that is

- to say,] through contemplation, he recognizes himself as God

- again, and thus returns from the illusion of individual existence

- to the universal totality of the divine state.[1]

This is an observation we can agree with, as long as by divine state is meant not an image of the divine shaped by Christianity but rather as buddhahood.

Why did Jung interpret mandalas as images of the divine? For him,

mandalas were ‘‘real or natural symbols of unity, as they appear to us in dreams

and visions,’’ i.e., ‘‘quaternities, or rather multiples of four, or squared circles.”

These ‘‘unifying symbols’’ or symbols of unity:

- are usually fourfold and consist of two intersecting pairs of

- opposites (e.g. right/left, up/down). These four points define a

Thus Jung perceives the central point, circle and quaternity as well-known symbols of the divine.

Archetypes?

Carl Gustav Jung also analyzed the function of the mandala, the protective circle. It seems to him to be ‘‘…the traditional antidote for chaotic states of mind.”[3] He was led to this realization not least by some of his patients, who in states of psychological dissociation or disorientation created mandalas and apparently used them as a center to attain inner order and regain unity of the psyche, the so-called self. Jung speaks of ‘‘an attempt at self-healing on the part of nature, which does not spring from conscious reflection but from an instinctive impulse.”[4]

Jung did not believe that all mandala representations were derived from chaotic or conflict-filled states. According to him, people all over the world draw, paint, carve in stone, and build such spontaneous imaginative productions, when they let them “happen psychically,” arising without consideration from within. Such mandalas arising from dreams and visions are to be found in Europe, says Jung, above all in medieval natural philosophy, which leaned on ecclesiastical use of allegory based on sets of four, for example four evangelists, four rivers of heaven, and four winds.

We know that Jung himself painted mandalas, the first in 1916, the Systema Mundi Totius.

Jung used his theory of archetypes to explain the fact that mandala-like structures—among which he also included the cross and other quaternity symbols—are found worldwide. Archetypes were primeval images based on an ‘‘unconscious disposition of as it were universal distribution’’ (impersonal collective unconscious), a disposition capable in principle of producing the same, or very similar, symbols in all times and places. ‘‘The archetypes are rather like organs of the pre-rational psyche.

They are perpetually passed on, identical forms and ideas without specific content.” [5] According to Jung, it is therefore the collective unconscious that brings forth the archetypal symbols of unity, such as the forms of mandalas.

Difficulty of comparison

Jung recognized that a mandala does not really have to be painted or drawn, but can also be danced, as some of his female patients did, or executed and experienced in ritual. On the basis of an early Christian ritual described in the apocryphal Acts of John (ca. third century), he exemplified the ritual circle process as a:

- mystical round dance that Christ arranged before his crucifixion.

- He ordered his disciples to take hold of each other’s hands and

- form a circle. He himself stood in the middle. They moved in the

- circle while Christ sang the song of praise.[6]

What Jung wrote in his commentary on this Christian round dance could be reused almost uncut as a commentary on a Buddhist mandala round-dance:

From time immemorial the circle and center has been a symbol of the divine, illustrating the unity of the incarnate god: the single point in the center and the many of the circumference. Ritual circumambulation often leans consciously on the cosmic allegory of the rotating night sky, the ‘round dance of the stars’, an idea still contained in the old equation of the twelve Apostles with the constellations of the zodiac. . . . In every case the ceremonial round dance aims at and brings about the impression of

the circle and center as well as the moving of each point of the circumference into the center. Psychologically this arrangement denotes a mandala and thereby a symbol of the self, on which are aligned not only the individual I, but at the same time many others of like mind or linked destiny.[7]

For Jung, Christ standing in the center was someone towering above the ordinary man and embracing unity, a symbol for the self of every human being; the mandala round-dance was an act of dawning of higher consciousness, understood as the connection established between the consciousness of the individual and the higher symbol of unity.

C.G. Jung was aware that despite the archetypical origin he assumed, there were differences between the various mandala forms. He pointed out a divergence between Christian and Buddhist mandalas, whose significance should not be underestimated: a Christian will never say in his contemplation, “I am Christ,” but only, with Paul, that Christ lives in him. A Buddhist, however, meditates in the conviction that he can be and ultimately is Buddha.

This raises the complicated topic of the comparability of different religious contents and concepts. As mentioned, Jung’s commentary on the round dance of Christ resembles one on the Buddhist mandala ritual — with the exception of the last part, which speaks of the self and the “I,” terms that must obviously not be described indiscriminately as identical with Buddhist concepts of the same name. Is consciousness in Buddhism to be understood the same way as it is for us? Does the ego in Buddhism correspond to the ego of Jung? Does Buddhism also recognize an unconscious, and, if so, does the idea have anything in common with the unconscious of the Jungian school?

These are questions that cannot be answered here, all the more so since both Buddhism and Western thought have developed a variety of psychological concepts.

So the point of the last minutes should not be to compare Jung’s depth psychology in detail with the Tibetan Buddhist body of thought; rather I should like to formulate a few basic ideas about the mandala ritual as a stimulus to independent study of the mandala phenomenon.

Dangers and opportunities of the center-ritual

A visualization — not only one about a mandala — is a typical center ritual. Visualization is thus a process of seeking and finding one’s own center. Even if Buddhism strives to dismantle, undo, and dissolve the ego, the meditator stands at the center of the ritual events. Does this mean a visualization, and in particular a mandala visualization, is tantamount to an egocentric practice, an ego trip? The impression could actually arise from a superficial evaluation of the process. But what actually happens in a supposedly

egocentric visualization--or better, what ought to happen? The closer a meditation comes to the center, the center of the mandala and the center of the deity whose form the meditator has assumed, the more it loses substance and concreteness, until in the end the emptiness of everything, even of the meditator himself, is recognized, including his own manifestation as a deity.

In addition, the whole course of the mandala ritual makes it clear that the goal of the diverse spiritual and meditative efforts cannot be one’s own release alone. The goal is instead twofold: one’s own liberation for the benefit of all other living beings.

Indisputably, however, there is a danger that visualization may lead not to a dissolution of the ego but to its enhancement. After all, the person meditating feels himself to be a god or goddess; he says to himself again and again he has divine qualities and is enlightened! This latent threat of egocentrism explains the urgency of the Buddhist warning that under no circumstances should one practice visualization thoughtlessly and unaccompanied by a spiritual teacher.

Through demanding yoga practices, destructive powers can also arise. In this connection Jung speaks of:

- the sphere of the chaotic personal unconscious, in which

- everything is found that one would willingly forget and that one

- would at all costs admit neither to oneself nor to another and

- would anyhow not take to be true.[8]

Meditation, too, touches on these inexpressible matters. Carried out correctly, the visualization process, as we have come to know it, has an autosuggestive effect the importance of which must not be underestimated. A visualization is not only about experiencing and recognizing emptiness but also at the same time is about accepting the here and now, living together with other beings who are empty and devoid of any essence but nevertheless need our support and affection. The meditator accepts his own being, admittedly having attained insight into his true nature and confidence in himself.

In this process, the role of the person who leads and escorts the mandaladancer raises a problem, which concerns the phenomenon of transference (to use a term from Western psychology), of becoming totally dependent on the guru. Every student needs the leadership of a guru, and it is necessary for him to imagine the guru as Buddha, in fact that guru and Buddha are one for him. This can result in unwelcome commitments, but Tibetan Buddhists, at least the far advanced among them, have also recognized this danger. Milarepa, for example, was once able to advise Gampopa, ‘‘Regard even your guru as an illusion!’’

Suffering microcosm — suffering macrocosm

We live in a time in which we are coming to sense ever more clearly how strongly we are bound up with the outside world, how much we are part of a living, life-supporting system contained in the so-called biosphere, which extends from the skin of our planet or beyond to the depths of the earth and the ocean. Human beings threaten at least three of the elements mentioned repeatedly in the

mandala ritual, namely earth, water, and air. These elements are exploited, manipulated, and polluted by us — and slowly, modern civilization is starting to understand that by felling entire primeval forests, eradicating many plant and animal species, endangering genetic diversity, destroying the ozone layer, overusing the soil, and allowing nuclear and chemical contamination it is polluting itself. In this situation it is worth reflecting on the Tantric Buddhist idea that we are part of a cosmic whole, limbs of this world. Of

course when we say that our arms and legs are the continents of the universe, we do take it literally; rather such an allegorical mode of expression means: the world is us, and we are the world; or, in the words of Tantric Buddhism,‘‘As it is without, so it is in the body.’’ When the world or a part of it is suffering, I too suffer; when I suffer, the world suffers. When I harm the world, I harm myself and other beings and components; when I exploit them, I exploit myself!

We have encountered various aspects of the fundamental wisdom of Tantric Buddhism, according to which structures and events recur endlessly from the expanse of the macrocosm to the minuteness of the microcosm, and everything appears as a copy of another copy. In other words, we have discovered that the person and all other beings are not part of the cosmos but contain the cosmos within themselves, in such a way that all beings are constructed similarly to the macrocosm and the same processes take place within them, as in the world around them. This is a view we also find formulated by early Christian theologians, such as Origen (ca. 185–253):

- Understand that you have within yourself herds of oxen . . .

- flocks of sheep and herds of goats. . . . Understand that in you are

- even the birds of the sky. And marvel not if we say that these are

- within you, but understand that you yourself are another little

- world and have within you the sun, moon and stars.[9]

Such a view implies the recognition that outside and inside and object and subject represent pairs of opposites that lead to confusion and wrong conduct and must therefore be overcome.

The world view of Tantric Buddhism denies the possibility of tackling impurities and faults selectively, postulating instead holistic action that takes into account mutual interrelations and the right of all of nature to exist. Mandala meditation is an aid that makes it easier to discern far-reaching interconnections, while time after time reminding us of the divinity, or buddhahood, that underlies everything and allows us to experience it. What a difference from the numerous rites of violation of our modern technologically oriented and consumerist world, with its attitude that the world belongs only to us and is our rightful property.

This article is republished from the following publication. For further reading:

MANDALA – SACRED CIRCLE IN TIBETAN BUDDHISM,

Written by Martin Brauen, Arnoldsche/Rubin Museum of Art, 2009.

About the Author

Dr. Martin Brauen is a highly dedicated ethnologist with intensive fieldwork research experience in the Himalayas/Tibet and India – ethnology being the branch of anthropology that analyzes and compares human cultures, most particularly their social structure, language, religion and technology. He is arguably the most knowledgeable curator specializing in this region of the world. Dr. Brauen was employed by the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich since joining its staff as an assistant curator in 1971. In 1979, he was promoted to the post of Deputy Director and Head of the Department of Himalaya/Tibet and the Far East. He was once again promoted in 1987, this time to the prestigious position of Curator/Head of the Department of Himalaya/Tibet, Japan and China. From 1999 -2008, he held the position of Senior Curator of the same department.

Footnotes

- ↑ Jung, Carl Gustav. 1981: Mandala. Bilder aus dem Unbewußten. Olten, Walter-Verlag 1977, repr. 1981: 81.

- ↑ ----- 1954: Von den Wurzeln des Bewußtseins. Studien über den Archetypus. Zürich, Rascher Verlag: 475.

- ↑ ----- 1954: 13.

- ↑ ----- 1981: 116.

- ↑ ----- 1972. Preface and psychological commentary to the Bardo Thödol. In: Das Tibetanische Totenbuch, ed. W.Y. Evans-Wentz, 1935/1953, 7th edn Olten, Walter-Verlag 1972: 49.

- ↑ ----- 1954: 319.

- ↑ ----- 1954: 322.

- ↑ -----1948: Symbolik des Geistes. Studien über psychische Phänomenologie. Zürich, Rascher Verlag: 467.

- ↑ Origen in: Leviticum homiliae, V, 2; according to Jung 1981: 75.