The Rabbit on the Moon Legend

Click here to see other articles relating to word The Rabbit on the Moon Legend

Like many aspects of Japanese culture, the Rabbit on the Moon legend comes from China. But as you’ll see, the Chinese legend goes even further back to ancient India and Buddhism.

All of the following legends show that our ancestors, no matter where they lived on earth, all looked up to the stars and moon in an attempt to find meaning.

Meaning for our lives and our place in the universe.

Let’s begin the telling of this legend in India, thousands of years ago, and then chronologically and geographically work our way toward modern Japan.

The Jataka White Rabbit

India is the most likely source of origin for the rabbit on the moon legend.

The Jataka, otherwise known as the “Previous Life Stories,” tell the tales of Buddha Shakyamuni’s 34 previous lives before being reborn as a human as Siddhartha Gautama and attaining enlightenment.

In story number 6, he is reborn as a white rabbit. Even though he’s an animal, this rabbit is so virtuous, beautiful, and good that the other animals treat him as a king and admire his wisdom. The three animals that became his closest students were an otter, jackal, and monkey.

One night, the rabbit instructed them that on the following evening there would be a full moon, and was a holy day (the Uposatha day of fasting), and that any beggars who needed aid should immediately be given food.

The rabbit realized later on that while his companions had a variety of ways to feed a human being, he had none. Only the bitter grass clippings that he ate each day. He immediately decided that if the opportunity arose, he would offer his own body as meat.

Hearing this thought, the god Shakra (aka Sakka, or Indra), the Lord of All Gods, decided to descend to earth and test the rabbit’s conviction. He appeared as a hungry beggar.

The otter brought fish. The jackal brought a lizard and a stolen pot of milk. The monkey brought mangoes.

But the rabbit had nothing to offer. So with the help of the other animals and the man he built a fire. As soon as the fire was blazing he jumped on top of it.

Shakra was greatly moved. He quickly reached into the fire, pulled out the unscathed rabbit and held it above his head, displaying him before all the gods in his mighty glory.

To honor the rabbits selfless sacrifice, Shakra placed the image of the rabbit on the top of his palace, and most importantly to this story, carved the rabbits image onto the moon.

This is where the “rabbit on the moon” idea comes from. The rabbit was engraved on the moon so that people across the world would forever have a symbol of piety, righteousness and sacrifice to look up to.

The rabbit had nothing to offer but himself, and this was the greatest gift of all.

Chang’e and the White Rabbit

The Buddhism of India was exported into China where it took root and assimilated with the existing culture. Many of the Buddhist legends became interwoven with existing Chinese beliefs and folk tales, such as those from Daoism.

One such Daoist story is about a young woman named Chang’e (嫦娥). She is the Moon Goddess and the Chinese equivalent of “The Man in the Moon.”

The quick version of the story is that Chang’e and her husband were both immortals. Through an altercation with the Jade Emperor, Lord of Heaven, they were banished down to the earth to live as mortals.

In an attempt to seek their immortality once again, her husband Houyi sought the way back and was fortunate to meet the Queen Mother of the West, a Daoist deity. Seeing his pious nature, The Queen Mother gave Houyi a magic pill of immortality, but warned him that they each only need to eat one half of the pill.

Unfortunately Chang’e was too curious and swallowed the entire pill herself. She rose upward into the sky as her husband looked onward, unable to do anything but cry. She kept rising up, and up, until she landed back on the moon.

Luckily she wasn’t alone! A “Jade Rabbit” lived there as well, and he had the job of constantly making immortality elixirs in his pot.

Throughout Chinese history the “moon rabbit,” as inherited from the Indian legend of Buddha Shakyamuni’s sacrifice, had been called many names, such as Jade Rabbit (玉兎) or Gold Rabbit (金兎). The Jade Rabbit refers to Daoism and immortality, while I believe the Gold Rabbit most likely refers to Buddhism and enlightenment. Here you can see the interwoven cultures.

The white rabbit (aka Jade Rabbit) is connected to the Dao because he was making an immortality elixir. Long life and eventual immortality was one of the goals of Daoist practitioners, who regarded Jade as the highest material substance (as personified by the Jade Emperor). They were known for collecting herbs or special ingredients and mixing them together in a pot in an attempt to create immortality pills.

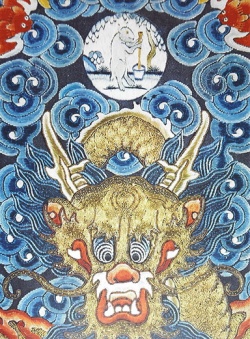

This image is of an 18th century Qing Emperor’s robe. The white rabbit is on the Emperor’s Robe because it was considered a Daoist symbol of long life. The Dragon represents the Emperor and “The Will of Heaven.”

The Chang’e legend was part of traditional folklore that became very popular in the Tang Dynasty (609 – 907 AD). On each Mid-Autumn day, the full moon of the 8th lunar month, people throughout China set up altars and put their pastries and cakes on the altar to be blessed by Chang’e. When they eat the pastries and cakes, they become beautiful.

This is called the Moon Festival, Mooncake Festival or Mid-Autumn Festival, and there is an accompanying parade at night where people carry lanterns with rabbits on them.

In literary culture Chang’e is also found in Journey to the West, the inspiration for Dragon Ball. Here, she is banished from Heaven by the Jade Emperor just like Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie, but through the process of redemption is allowed to make her way back up to Heaven and eventually to the moon.

Likewise, the famous Tang Dynasty poet, Li Bai, wrote of this rabbit in his poem, “The Old Dust,” saying, “The rabbit in the moon pounds the medicine in vain.”

These Indian and Chinese legends became intermingled and were then passed on to Japan.

The Japanese White Rabbit

Japanese culture is a mix of imported Chinese, Korean and native beliefs with its own unique flavors and disciplines.

A version of the Jataka stories from India can be found in the Japanese anthology, Konjaku Monogatarishu (今昔物語集), a classic source of many Japanese legends and both Buddhist and Shinto culture, written between 794 and 1185, a time of great trade with China.

It is retold here as a children’s story.

Many of the legends in the Konjaku Monogatarishu feature animals that can think and talk like humans. They sometimes appear bipedal and anthromorphic, with morality and feelings, just like the animal characters in Dragon Ball, such as Boss Rabbit, Oolong and Puar.

In the Japanese version of the Chang’e story, when she makes it to the moon and sees the white rabbit, the rabbit is pounding rice in a mortar, not an elixir in a pot. The rabbit’s name is Tsukiyomi (月読), the same name as the moon god in Shinto and Japanese mythology.

This is because Tsukiyomi is said to have killed Ukemochi, the rice goddess. Tsukiyomi pounds rice in a pestle and mortar because he harvested the grains of rice from the moon and is turning them into cakes. The “mochi” desserts come from Ukemochi.

The same idea of a rabbit making mochi (instead of elixir) is found in the Korean version of the story, but I don’t know which one came first.

Today, just like in China and Korea, people in Japan celebrate the first day of autumn by eating mochi. The first day of Autumn is an equinox, and therefore a perfect “moon viewing day” in Japan. People look up at the moon and see the rabbit. The rabbit on the moon makes the mochi. Then they eat the mochi. Makes sense, right?

This was common folklore and culture that Japanese citizens grew up with, just like Easter in America. It’s a national holiday that is celebrated throughout the country.

For example, the Rabbit Song, or “Usagi,” as it’s known, is a children’s song that mentions the rabbit on the moon and the festival. This song is as common in Japan as “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” is in the United States.

Here are the lyrics:

“Rabbit, Rabbit, what do you see when you jump?

The fifteenth night moon is not nearly enough.

Jump into the night and dance with the moon.

No time to sleep, the party is just starting!Usagi usagi nani o mitehaneru?

juugoya no tsuki dake ja monotarinai

yoru ni tobidashite tsuki to odorou

nemurenai utage wa mada mada kore kara!”

The song is sung by young children throughout Japan, including Dragon Ball’s target audience, and they’re all familiar with the legend.

Toriyama wrote his comic for young Japanese boys, and so he purposefully appealed to what they would be interested in during their youth. He took the legend of the rabbit on the moon and incorporated it into Dragon Ball.

This slice of Japanese culture is in the comic for seemingly no other reason than to be funny. And I’m not even sure why it takes up an entire episode and issue, as it isn’t integral to the story. It’s just something that happens along the way.

Japan only has a 2% Christian population, so there aren’t many people who celebrate Easter. The legend as depicted in Dragon Ball obviously has nothing to do with Easter, as I’ve thoroughly explained, but I thought it a fitting day to tell such a story to a primarily Western audience.

Toriyama fills in the blank of the Japanese version of the rabbit on the moon legend using Goku, Boss Rabbit and his Rabbit Gang. The rabbit made it up there because Goku took him up there!

He and his gang presumably would have stayed up there forever, but Master Roshi destroyed the moon with a Kamehameha while fighting against Goku during the 21st Tenkaichi Budokai later in the series.

Oops.

Did they die, as would be logical?

No, because in the book “Dragon Ball: Adventure Special,” (published December 1, 1987), Akira Toriyama explained that “They’re drifting through space.”

Toriyama was probably trying to be nice by not killing them off. But to me, drifting through space for the rest of your life is even worse than death and going to the afterlife.

Oh well.

In conclusion, the point I’m trying to make is that the entire reference to all of this ancient culture is depicted in 1 panel, of 1 page, in 1 issue of a comic. Yet it speaks volumes if you know the full history of what is depicted.

And now you do.

So the next time you see Boss Rabbit you’ll remember all of the ancient culture and the thousands of years of history that made his creation possible.

Resources

White Rabbit on Emperor’s Robe

Japanese Wooden Rabbit Toy

Bunny Rabbit on the Moon

Jataka Stories

Moon Rabbit on Wikipedia

Chang’e on Wikipedia

Carrotizer Bunny on Dragon Ball Wikia

Japanese Children’s Story on YouTube

Jataka Stories 2

A French Article on Dragon Ball’s Moon

Li Bai’s Poetry

Prints of Japan – In Depth Article on Japanese Mythology

Chang-e Moon Goddess and White Rabbit