The Secret Society

I dispelled the three worlds by means of amorous play And I fell asleep in the sport of sexual union How lovely, o Dombi, is your coquetry The twice-born is outside, the kapalika is inside your hut By you, o Dombi, the whole world has been disturbed And for no reason, the Moon has been agitated Some are there who speak ill of you But those who are discerning do not remove you from their throat Kanha sings of the amorous Chandali There is no greater harlot than you, o Dombi

This song, written sometime around the 10th century CE by the Buddhist siddhacharya Kanha or Krishnapada, is from the earliest collection of folk-songs in what was then the proto-Bengali language. Called the Charyagiti or ‘Songs of Realisation’, these songs were performed by a new kind of Buddhist adept, the tantric siddhas or ‘the perfected ones’

who weren’t monks. Followers of the esoteric ritual doctrines of the Vajrayana (the Way of the Thunderbolt), the siddha community of men and women rejected conventional society, and even the popular Mahayana Buddhism, for a life of intense yogic practice and ritualised sexual union.

Roughly speaking, the 8th to the 13th centuries CE were a great time for Buddhism in eastern India (and in some other regions like Kashmir). Under the patronage of the powerful Pala monarchy of Bengal and Bihar, the monastic universities

of Nalanda and Vajrasana (Bodh Gaya) were flourishing, and new viharas like Vikramashila in Bihar and Somapura in Bengal (now Bangladesh) brought in fresher perspectives on popular Buddhism, especially the tantric way of Vajrayana.

In terms of folk culture, what the Vajrayana ushered in was revolutionary. Over a period of about 500 years, the arts boomed. From stone sculptures and metal casting to miniature paintings, mural paintings as well as large canvases on cloth, the effects were seismic, and international. As art historians Susan L. Huntington and John C. Huntington depict

in their book Leaves From a Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala India and Its International Legacy, under the Palas, the Buddhist heartland of Magadha in Bihar became a melting pot of Asian and Southeast Asian cultures, with monks and lay

worshippers coming to worship, and carrying away with them examples of this burgeoning religious art, which would go on to influence their own countries.

This period was brought to an abrupt and tragic end, as the viharas first fell victim of the religious iconoclasm of invading Afghan armies and thereafter, without the institutional support of the monasteries, Buddhism was entirely eclipsed by a resurgent Hinduism.

However, while a unique religious and artistic way of life perished in the country of its birth, it continued to thrive elsewhere, most notably in Tibet and in Nepal. It is in this context that I came across an 11th century painting on

cloth, from the Kathmandu Valley, in the online archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This gorgeous painting of the Chakrasamvara Mandala is called a paubha by the Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley. Master craftsmen and artists

for over a millennia, the Newars have always been part of the same cultural continuum as norther and eastern India. As traders who traversed the lucrative routes from the Gangetic plain to the Tibetan plateau and China, their role in

transmitting Indian artistic styles—especially Buddhist art traditions—to Tibet is second to none. The famous Tibetan cloth painting style called the thangka, is basically the paubha by another name.

Paubha itself is the Newar word for the eastern Indian pata, and the painting of the tantric deity Chakrasamvara in an erotic embrace with the goddess Vajravarahi, is one of the earliest surviving examples of a style that, in the 11th century, was thriving in contemporaneous Indian culture, especially in Bengal, Bihar and Odisha.

The patachitra or painting on cloth, had been popular in India since at least the time of king Harsha Vardhana of 7th century Kannauj. Bana Bhatta, the author of Harshacharita, speaks of cloth banners being carried in processions, or

being used by itinerant storytellers, as a visual guide to their tales. Indeed, the 8th century Buddhist tantric text, the Manjushrimulakalpa, even describes the process by which a pata of the Bodhisattva Manjushri should be made. Evidently then, this was a major form of painting style in India.

In fact, it still is, as the thriving cultural practice of patachitra production, especially in Bengal and Odisha, shows us. The end use of such painted scrolls too remains the same—a visual guide to telling a story. The only aspect

of this that no longer exists in India is the Buddhist context of this praxis. In India, one could say that the Buddhist paintings of the Pala era were the high cultural incursion of a folk form that has since returned to its roots.

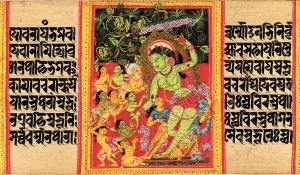

In fact, the trends were already there. A beautiful 12th century painting of the Buddhist goddess Shyama Tara (Green Tara) dispensing boons is actually a miniature watercolour illustration on a palm-leaf manuscript of the Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita, an important Mahayana sutra. This manuscript was executed in Bengal as a royal commission of a Queen Vihunadevi. More so than any large-scale painting, this miniature, with its rural setting, its depiction of dense

foliage, the group of ecstatic devotees and benevolent, larger-than-life Tara—probably modelled after the commissioning queen—belongs more to a folk medium.

What is remarkable, however, in this miniature’s relationship to the Nepali paubha, is not the deity, but the worshippers. In the Tara painting, these people aren’t monks, but seem to be a group of tantric adepts, led by a white-

haired guru. Their ecstatic poses, ranging from the dancing figure in the bottom left corner to the supplicating figures closest to the deity, give a sense of utter immersion and profound bliss.

The Buddhist technical term for supreme pleasure is mahasukha or the ‘Great Bliss’, which is, in tantric terms, the same as nirvana. In this extreme yogic state, the adept is cut off from the ties of samsara, and perceives the world hidden behind the false

dualities of human sense perceptions. It is just such an adept who can lay claim to being called a siddha, and in turn continue the siddha lineage by becoming the Guru to his or her own disciples. The Vajrayana was primarily propelled by

this community, some of whom were monks, while many others weren’t. When we look at the painting of the Chakrasamvara mandala, what catches the eye is the depiction of the siddha community in the background, those who are simultaneously visualizing and worshipping Chakrasamvara and Vajravarahi through their tantric practice in cremation grounds.

And these aren’t just any cremation grounds, but the eight great Indian charnel grounds (maha-smasana) that are both actual spaces and internalised fields of meditation—Chandogra, Gahvara, Jwalakula, Subhisana, Attattahasa, Lakshmivana, Ghorandhakara

and Kilakilarava—with their own sacred trees (vriksh), protectors (dikpatih), serpents (naga) and clouds (megha). This cremation ground iconography, as well as the reference

to the kapalika in the song quoted at the beginning, serves to highlight the cultural realm and technical terms that tantric Buddhism shared with its great rival—tantric Shaivism.

Indeed, the myth of the tantric Buddha Chakrasamvara is predicated on his defeat of Maheshwara in a straight battle on Mount Kailash and the latter’s eventual conversion to

Buddhism. You can see this in the painting too: Chakrasamvara and Vajravarahi can be seen trampling on Shiva and his consort, Kalaratri.

But let us return to the scenes depicted in the periphery of the mandala. In fact, the cremation ground scene can’t really be referred to as a ‘background’ in the conventional

sense. The figures and the locales underpin the entire mandala, as it is this community of divine creatures, siddhas, yogis and yoginis are the ones that are creatively giving form to the deities through their activities. In later

Tibetan traditions, depictions of deities, mandalas and cremation ground communities became more rigidly stylised, as can be seen in the 15th century Tibetan thangka of the exact same scene, preserved in The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in California.

In these latter depictions, and indeed in modern thangkas that are being produced even today, the deities at the centre of the mandala overpower the periphery, and the community of freewheeling, anonymous tantrikas are replaced by rigid iconographic forms of well-known Indian mahasiddhas who formed tantric lineages to which all the different sects of Tibetan Buddhism owe their existence.

So who were the people depicted in the 11th century painting? They remain anonymous, lost to us as distinct individuals. To my mind, they best exemplify the community mentioned in the 8th century tantra called Guhyasamaja, which translates to ‘the secret society’. What were these anonymous men and women doing, convinced as they were of the efficacy of the tantric path to enlightenment looking for?

From texts such as the 9th century Hevajra Tantra, which is dedicated to the tantric deity Hevajra and his consort Nairatma and the slightly later Samvarodaya Tantra dedicated to the deities in the painting under discussion, we read about ganachakras or the ‘secret communion’ of like-minded yogis and yoginis in liminal spaces away from mainstream

society. In these gatherings, adepts would seek out other members of the ‘secret society’ by means of choma or secret signs. Thereafter, under the leadership of the Guru, the men and women would perform ritual dances, eat ritual feasts of ‘impure’ substances like meat and alchohol, and engage in ritual sex, to the accompaniment of Charya songs and music. All of these activities would be celebratory and help the adepts to try and reach the state of the Great Bliss.

When we look at the 11th century painting, we see this is exactly what is being depicted—men and women dancing, having sex, talking, engaging in ritual meditation with skull arches and corpses and feasting, all the while surrounded by the pyres, human remains, jackals and skulls of the charnel ground, an ‘impure’ space, and thus perfect for such congregations.

The fact that the historical Krishnapada, with whose song we opened, was a prolific writer of tantric texts and commentaries, a notable pandita, and a prime disseminator of both the Hevajra Tantra and the Chakrasamvara Tantra as

well as the cult of Vajrayogini/ Vajravarahi, goes to show the eclectic nature of this community. Some of them were also monks, but most were lay householders who studied the tantras with lineage Gurus, tantric priests (Vajracharya)

and with monks in the viharas. To find echoes of that time, we need only visit a modern tantric sacred site like Tarapeeth in West Bengal or Kamakhya in Assam. Both sites are renowned for their powerful tantric female deities (the

Tara of Tarapeeth, though under a Hindu guise, has the same core mantra as the older Buddhist Tara), and also for their adjacent cremation grounds, where even today you will find yogis and yoginis residing as members of a liminal community of tantric seekers.

In the popular Newari Buddhist imagination, the Kathmandu Valley is but a gigantic mandala presided over by Chakrasamvara. In the monasteries of Patan, one of the three main cities of the Valley, you will still find painters making similar paubhas, reciting Sanskrit tantras and sutras, and undergoing secret tantric initiations with their

partners. Indeed, at the bottom right of the 11th century painting, you can see a depiction of the Newari couple who commissioned the painting of this paubha, so that they could, together, gain the paradise of Chakrasamvara. Although, we will never know who these people were, they live with us still, a guhya-samaja immortalised in art.

Select Bibliography

Per Kvarne Buddhist Tantric Songs: A Study of the Caryagiti

Rob Linrothe Ruthless Compassion: Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art

Elizabeth English Vajrayogini: Her Visualizations, Rituals, And Forms

David Barton Gray The Chakrasamvara Tantra

David Snellgrove Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Indian Buddhists & Their Tibetan Successors

Ronald M Davidson Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement

Christian K Wedemeyer Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions

Nihar Ranjan Ray Bangali’r Itihash (A History of the Bengali People)

Nupur Chaudhuri and Rajat Kanti Ray Eros and History: Sahajiya Secrets and the Tantric Culture of Love

David Templeton Taranatha’s Life of Krishnacharya/Kanha

David N Gellner Monk, Householder and Tantric Priest: Newar Buddhism and its Hierarchy of Ritual