The Sitting-in-Bed Ceremony and Other Strangeness

If you’re reading about Tibetan history on the internet, you might come across references here and there to a Tibetan ritual called the “sitting-in-bed ceremony”. When I first saw this term, it struck me as very strange indeed. As I found more examples of this phrase (and alternatives like the “sitting-on-the-bed ceremony”) it became clear that it only appeared on Chinese government and press websites.

Here’s an example, from the Chinese government’s version of how the present Dalai Lama was chosen and enthroned:

Chiang, then chairman of the Executive Yuan, reported to the Nationalist Government on 31, Jan, asking for permission that the lot-drawing be exempted and allow Lhamo Toinzhub be enthroned as the 14th Dalai Lama. Chiang also asked for fund for the sitting-in-bed ceremony. [See the full text here]

There’s no explanation of what this ceremony entails, though it certainly brings a strange image to my mind. Lets look at another website, this time an official Chinese newspaper’s account of the enthronement of the 11th Panchen Lama (that’s the Chinese government’s choice of Panchen Lama, not the Dalai Lama’s, whose whereabouts are unknown):

The sitting-in-the-bed ritual of the 11th Panchen Lama was held in the Yige Quzeng Hall on the second floor of Laburang. Only by sitting in the bed at Yige Quzeng could the Panchen Lamas be qualified, since the bed of all previous Panchen Lamas was there. The 10th Panchen Lama, who was enthroned in the Tar-er Monastery in Qinghai Province due to historical reasons, made up the enthronement ritual in the Yige Quzeng Hall after he came back to Xigaze. [See the complete, and rather lengthy account here]

Well, that’s fine then. It’s a funny Tibetan ritual in which the Dalai and Panchen Lamas have to sit on the bed of their predecessor before they can be enthroned. Hmm. I don’t know about you, but I’m still not convinced.

- * *

Here’s what I think this “sitting-in-bed ceremony” really is — just a bad translation that has somehow become standard in Chinese discussions of Tibetan Buddhism. I suspect the original Tibetan phrase is probably khri la bzhugs, literally meaning “to reside (or sit) on the throne,” often in the context of an enthronement ceremony. The phrase goes way back, and can even be found in the Dunhuang manuscripts (you can find it in Pelliot tibétain 1068 here).

You can probably see where I’m going now. The Chinese translation of this term that has become standard is 坐床 zuo chuang, literally “sitting-bed”. It’s that character 床 chuang that is the problem here. If you look in Tibetan-Chinese dictionaries, you see that the Tibetan khri is given a number of possible Chinese characters, meaning throne, couch or bed. This might come as a surprise to readers of Tibetan (it did to me), who have only ever come across khri meaning “throne”.

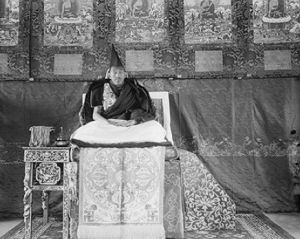

But that depends on what a throne is. From a European point of view, a throne should be a very grand sort of chair, but in Tibetan culture (and many other Asian cultures) it’s more of a raised platform. The photograph of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama at the top of this post shows one such throne. Here is another, smaller throne (also for the Dalai Lamas at the Norbu Lingka), photographed in the 1930s:

Norbu Lingka ThroneAs you can see, the distinction between a throne, a couch and a bed is not as distinct as it might at first seem. The Tibetan throne pictured above might best be described in English as a divan (which the OED defines as “a long seat consisting of a continued step, bench, or raised part of the floor, against the wall of a room, which may be furnished with cushions, so as to form a kind of sofa or couch.”)

That said, nobody would describe Tibetan thrones like these as a “bed”, and I still think that “bed” is the worst of the available Chinese translations of Tibetan khri. The second stage of translation, from Chinese into English, leads to the entirely misleading phrase “sitting-in-bed ceremony.” So if you come across this phrase, keep in mind that the Tibetan behind it just means “enthronement”.*

- * *

Why would this bad translation become standard in official Chinese literature, repeated again and again without question or correction? I think it betrays a lack of care, or a lack of interest in the actual nature of Tibetan culture. The authors of these pieces are inevitably making a political point, and once that point has been made, there’s no need to go any deeper into, for instance, what actually happens when a lama is enthroned. The strangeness of the misleading term “sitting-in-bed ceremony” can easily be dismissed as another example of the weird and wonderful culture of the exotic Tibetans.†

- * *

Endnotes

- Two other terms often found in the same Chinese sources are:

“Soul boy” (灵童 ling tong), referring to a candidate for recognition as a rebirth or tulku.

“Living Buddha” (活佛 huo fo), referring to a recognised rebirth or tulku.

These have no equivalent in Tibet, and rather than being bad translations, are Chinese terms with their own history in Chinese culture. In both cases, like the “sitting-in-bed ceremony”, the Chinese term is somewhat misleading, and the English translation of it even more so. “Living Buddha” has its own unfortunate career in the West.

† Of course, the Western media can be just as bad. There was an article last year on the Dalai Lama in the English Sunday paper The Observer entitled “Inside the court of the Tibetan god-king“. This was 2008, but that headline might as well have been written in 1908 (though the article itself was reasonable enough, and the headline was no doubt the work of a copy-editor, not the journalist).

- * *

Images

1. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama on a throne in the Norbu Lingka, photographed by Charles Bell, October 14, 1921. (c) The Pitt Rivers Museum. Bell described this event in his book Portrait of the Dalai Lama (Collins, 1946), p.336:

I am to take the Dalai Lama’s photograph again, this time it is to be in his own throne-roon in the Jewel Park Palace, the first time that anyone has photographed him in the Holy City.When I arrive with Rab-den, on the day and the hour appointed, the arrangement of the throne-room is not ready. I watch them arranging it. The throne is built up of two or three wooden pieces; the nine silk scrolls, representing the Buddha in the earth-pressing attitude, are already placed on the wall behind and above the throne… Below these scrolls red silk brocade covers the wall. The throne is four feet high, a seat without back or arms. It stands on a dais, eighteen inches high, with low balustrade of beautifully carved woodwork running around it. Hanging down in front of the throne is a cloth of rich white silk, handsomely embroidered in gold, with the crossed thunderbolts of the God of Rain. Chrysanthemums, marigolds and other flowers are arranged round the dais. This is the throne that is used on important occasions.

2. The throne in the Kesang Podrang palace of the Norbu Lingka, photographed by Hugh Richardson in 1936-1939. (c) The British Museum.