The Yogācāra Tradition: History and Texts

Chapter 2: The Yogacara Tradition: History and Texts

2.1 Origin and Development of Yogacara

2.1.1 Background of Yogacara

The origins of the Yogacara traditions in India are larges lost to us. It is true that many Buddhist scholars were participants in an ongoing conflict between Therav?da and Mah?y?na. The origin and development of the Yog?c?ra is concerned, is really a very difficult task to trace its exact origin. It is only the later followers of Buddha who formulated different schools of thought from the real teaching of Buddha. The Yog?c?ra is one of the two mainly schools of Mah?y?na Buddhism in India. It began in fourth century India and became one of the two principal Mah?y?na Buddhist Schools; M?dhayamika is another one, established by N?g?rjuna in 2th century A.C. The Yogacara is described merely as idealism. During its formative years, Vasubandhu is one of a triad of figures, including also Maitreya and Asa?ga, who developed this Indian Buddhist School during its nascent period. The exactly relationship between them is unclear. Some say that Maitreya is to Asa?ga, more of a historical influence than an active contributor to what became the Yog?c?rin philosophy1. Here, it may be point out that recent thinking in Buddhism has been forcing the scholars to accept the view that the Maitreyan?tha was the real founder of the system. The tradition goes like that live of his works were revealed to Asa?ga by Maitreya. Some of the scholars hold different view that he was a historical person and the teacher of Asa?ga and he was the real founder of the Yog?c?ra School.

Indian Buddhism in its long history, the development of philosophical thought may be classified into four categories2, each representing a way of interpreting the original teachings of the Buddha. These four philosophical schools in historical order were:

a) The Vaibhasika, or phenomenological school founded on the study of Abhidharma metaphysics, which influential in Kashmir and Ghandhara largely pertained to monks of the Sarv?stiv?da Order, and became a fundamental study of the Theravada Order.

b) The Sautrantika, which felt that the exponents of Abhidharma had deviated from the original teachings of the Buddha as expressed in the Sutras. The school insisted upon returning to the discoures as sources for the study of the Buddhahood.

c) The M?dhyamika School founded by Nagarjuna in the south of India in the first and second century Abhidharma. The Madhyamika system of philosophy is famous for its dialectics. It must be observed that the critical realism of the Sautr?ntikas led on the one hand to the dialectical absolutism and M?dhyamika and the idealism of the Vijñanavada on the other3.

d) Finally, the Yogacara/ Vijñanavada School, which arose in part as a reaction against the scholasticism. After the time of Nagarjuna, it tended to displace contemplative practice in the monasteries of India. This Yoga movement emerged in the third century Abhidharma. The Yog?c?ra School is also known as Vijñanavada (consciousness doctrine) School4. The Yogacara system of thought has traditionally been described as some form of metaphysical idealism. Yog?c?ra focused on the processes involved in cognition in order to overcome the ignorance that prevents one from attaining liberation from the karmic rounds of birth and death. Yogacara introduced several important new doctrines to Buddhism, including

vijñaptim?tra, three natures, three turnings of the Dharma-wheel, and a system of eight consciousnesses.

Asa?ga and Vasubandhu became the first identifiable Yogacarins, each having initially been devoted to other schools of Buddhism. Asa?ga attributed a portion of his writings to Maitreya, the Future Buddha living in Tu?ita Heaven. However, some modern scholars have argued that this Maitreya was an actual human teacher, not the Future Buddha. Maitreya appeared and transported Asanga to Tushita Heaven where he instructed Yog?c?rin works, that Asanga then introduced to his fellow Buddhists. All of Buddhism required a Yogacarin reinterpretation. Innovations in Abhidharma analysis, logic, cosmology, meditation methods, psychology, philosophy, and ethics are among their most important contributions. However, Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti have described Mahayana Buddhism in general as part of its doctrinal rebellion against the realist Hinay?na School.5 A.K. Chatterjee, defining ontological idealism from the Mahayana perspective as the meditation between nihilism and realism, is among those who have supported the position that Yog?c?ra is the absolutism and the idealism.6 Thomas wood, focusing on the inter-subjective aspects of Vasubandhu’s system, describes it as a doctrine of collective hallucination. 7 David Kalupahana rejects the description of Yog?c?ra as any form of metaphysical idealism, absolutist or transcendentalist, and urges a psychological interpretation. Thomas Kochumuttom argues for an interpretation of Yogacara as a kind of realistic pluralism,8 while Alex Wayman and Richard King have expressed reservations about the relevance of the question of idealism in Yog?c?ra at all.9

A correct appraisement of the system is a form of absolutism. It also conceived a new philosophical system that brought Mah?y?na thought to its full scope and completion. Yogacara sustained attention to issues such as: cognition, consciousness, perception, and epistemology, coupled with claims such, as “external objects do not exist”. This is the central problem of affecting a logical synthesis between idealism and absolutism. The Yog?c?ra School has established a systematic presentation of mind, a world of view based on their threenature theory and a path system of Buddhist practice. Yogacara itself is not a specific meditative practice, but is meant as a descriptive tool to understand situations of action and intention. The Yogacara is wise enough to perceive that idealism, when pressed, yields the absolutism by the sheer dynamism of its own inner logic10. Yogacara is a special metaphysical teaching that gives us a unique view of the mind and the universe. This is a school of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing phenomenology and ontology through the meditative and yogic practices. The goal is the complete clarification of consciousness into wisdom. The intention of the school is not to propound a mere philosophical viewpoint, but to develop a perspective, which will facilitate enlightenment.

Yog?c?ra discourse is founded on the existential truth of the human condition. There is nothing that human experience that is not mediated by mind. All most of emphasis of the Buddhist philosophy has been laid on subjectivity. This one was usually linked with the concept of reality. Another important feature of the Buddhist philosophy is the realm of experience. There are different phases of it, which can easily be discerned in this connection, the realistic phase, the critical phase and the idealistic phase11. Thus, the earliest phase of the Buddhist philosophical thought begin with the Sarv?stiv?da. This name is very significant on account of it’s meaning, according to which everything exists.

That really meant is all of the elements of existence. This school of thought accepted as many as 75 dharmas12. The dharma is treated as objectively real. This school is broadly converted under Therav?da. It may also be pointed out that Therav?da exerted little or no influence on the later development of Buddhism. Therav?da does not reveal any new system. The historical Sautr?ntika School is very great and important; it is this metaphysics that paved the way for the later development in Buddhist Mah?y?na. After appearing of Sarv?stiv?da, there are emerged another school has known as Sautr?ntika. The Sautr?ntika are also understood as Sarvastivada itself, aware of its own logical basis. They are not two schools, but two phases of the same metaphysical pattern. This school of thought accepted only 43 dharmas and rejected the rest as subjective. As far as the metaphysical position of this school is concerned: “ In his metaphysics the Sautr?ntika maintains three theses. Everything is transient and perishing (anitya); every thing is devoid of selfhood or substantiality (an?tma); every thing is discrete and unique (svalak?a?a)”13. This school accepts the reality of the objects of the external world. This school accepted pratyaksa as a true evidence of knowledge. The school has a historical importance because on account of its metaphysics it paved the way for the later Mah?y?na developments in the history of Buddhism. According to A.K. Chatterjee, “the Sautr?ntrika prepared the way of the Madhyamika on the one hand and the Yog?c?ra on the other, and is, in a sense, the parting of ways.”

This School pushes Mah?y?na Buddhism to its climatic conclusion by engaging in an extensive discussion on the nature and activities of our mental life and its potential for transformation from delusion to enlightenment. It has exerted a profound impact on the overall development of Buddhist philosophical deliberations and meditative practices. Yog?c?ra teach on Karma, meditation, cognition, and path theory had a powerful impact on the other

Mah?y?na schools that developed during the time of the importation of Yog?c?ra to Tibet and East Asia, such that much of the technical terminology on which other Mah?y?na schools based their discourse was absorbed from the various strands of Yog?c?ra15. Although Yog?c?ra is not quiet a living tradition in the way Zen Buddhism or Therav?da Buddhism is today. It is very much alive in some Asian Buddhist scholastic traditions, especially in Japan. It also remains a source of inspiration for contemporary Buddhist practitioners as well as Buddhist scholar. Even in China, where Yog?c?ra did no survive as a continuing scholastic tradition. Furthermore, the philosophical and psychological insights exhibited by Yog?c?ra have gained real traction among modern western Buddhist scholars who in turn are influenced the way Buddhism has been received in the west, where most if the dialogue between Buddhism and modern psychology has been taking place. Therefore, an engagement between Buddhism and modern psychology cannot afford to disregard the contribution of Yog?c?ra Buddhism. Yog?c?ra stands on the innovative frontier as one product of the cultural interchange. The system which Asa?ga and particularly Vasubandhu formulate, and were to present in a number of pithy treatises, not only present the Buddha’s original path of meditation in clear, scientific terms, but also delved into an analysis of the psychology of the mind.

2.1.2 Yogacara Literature

The most that can be said with anything approaching certainty is that there begins to become apparent, in some Indian Buddhist texts composed after the second century Abhidharma. Yog?c?ra, school of Buddhism, eventually became virtually extinct within India. It is the development of the logic of Buddhist thought and the philosophical importance of considering and analyzing the nature of consciousness and the cognitive process. Such

questions had, naturally, been of significance for Buddhist thinkers long before the second century AD. Mah?y?nas?tras did not begin to appear until roughly five hundred years later. New Mah?y?nas?tras continued to be composed for many centuries. Indian Mah?y?nists treated these S?tras as documents that recorded actual discourses of the Buddha. By the third or fourth century CE, a wide range of Buddhist doctrines had emerged, but whichever doctrines appeared in S?tras could be ascribed to the authority of Buddha himself. The ways, in which, adherents of the Yog?c?ra have discussed them after this period and, in many cases, the philosophical conclusions drawn by such thinkers. At this point, a historical overview of the development of the Yog?c?ra is given and designated major phases of the Yog?c?ra tradition and will outline the major textual resources available for the study of each. Then some scholars had already been mentioned that Vasubandhu is the key figure as far as the Yog?c?ra system is concerned. He has contributed a lot to the development of Buddhist philosophy in more than one way. It is said about him that in the beginning he was an adherent of the Sautr?ntika School. ADK is a makeable work, written from the Sarv?stiv?da point of view by him, though the work primarily deals with the Sautr?ntika School, but this is held in great esteem by all oilier philosophical schools of Buddhism.

The origin of the Yog?c?ra is shrouded in obscurity. Amongst the earliest literature, LAS contains some of the idealistic teachings. It contains references to ?laya, manovijñ?na and to ten bhumis. Another important work known as Da?abh?mikas?tra also contains the germs of the Yog?c?ra along with the Ga??avy?has?tra. There is another importance SDS, which also has one germs of the later Yog?c?ra idealism are of the view that Asa?ga might have also written some treatises16. The “nine Dharmas” accepted as canonical by the Mah?y?na as La?k?vat?ra, saddarma17 etc. The founding of Yog?c?ra is traditionally ascribed most of its

fundamental doctrines had already appeared in a number of scriptures a century or more earlier, most notably the SDS (the first Yog?c?ra text, explaining the hidden intentions of Buddha). Among the key Yog?c?ra concepts introduced in the SDS are the notions of “only cognition” (vijñapti-m?tra), three self-natures (trisvabh?va), the ?laya-Vijñ?na (storehouse consciousness), overturning the basis (??raya-par?v?tti), and the theory of eight consciousnesses.

Hence, the SDS, as the doctrinal trailblazer of Yog?c?ra, inaugurated the endemic categorical triune of the three turning of the wheel of dharma. Mah?y?nas?tras continued to be composed for many centuries. Buddhists had always maintained that Buddha had geared specific teachings to the specific capacities of specific audiences, the SDS established the idea that Buddha had taught significantly different doctrines to different audiences based on their levels of understanding; and that these different doctrines led from provisional antidotes (pratipak?a) for certain wrong views up to a comprehensive teaching that finally made explicit what was only implicit in the earlier teachings. In order to leave nothing hidden, the Yog?c?rins embarked on a massive, systematic synthesis of all the Buddhist teachings that had preceded them, scrutinizing and evaluating them down to the most trivial details in an attempt to formulate the definitive (nit?rtha) Buddhist teaching. Innovations in Abhidharma analysis, logic, cosmology, meditation methods, psychology, philosophy, and ethics are among their most important contributions.

Asa?ga’s magnum opus, the Yog?c?rabh?mi??stra,18 is a comprehensive encyclopedia of Buddhist terms and models, mapped out according to his Yog?c?rin view of how one progresses along the stages of the path to enlightenment. Vasubandhu’s pre-Yog?c?rin magnum opus, the Abhidharmako?a (abb. ADK) (Treasury of Abhidharma) also provides a

comprehensive, detailed overview of the Buddhist path with meticulous attention to nuances and differences of opinion on a broad range of exacting topics. According to tradition Asa?ga converted Vasubandhu to Yog?c?ra after having himself been taught by Maitreya; he is not known to have had any other notable disciples. Tradition does assign two major disciples to Vasubandhu: Dign?ga, the great logician and epistemologist, and Sthiramati, an important early Yog?c?ra commentator. It is unclear whether either ever actually met Vasubandhu. They may have been disciples of his thought, acquired exclusively from his writings or through some forgotten intermediary teachers. These two disciples exemplify the two major directions into which Vasubandhu’s teachings split. After Vasubandhu, Yog?c?ra developed into two distinct directions or phase:

a) A logic-epistemic tradition, exemplified as Dign?ga, Dharmak?rti, ??ntarak?ita, and Ratnak?rti.

b) An Abhidharmic psychology, exemplified as Sthiramati, Dharmap?la, Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang), and Vin?tadeva.

While the first phase focused on questions of epistemology and logic, the other phase refined and elaborated the Abhidharma analysis developed by Asa?ga and Vasubandhu. These phases were not entirely separate, and many Buddhists wrote works that contributed to both phases. Dign?ga, for instance, besides his works on epistemology and logic also wrote a commentary on Vasubandhu’s ADK. What united both phases was a deep concern with the process of cognition, i.e., analyses of how we perceive and think. The former phase approached that epistemologically while the latter phase approached it psychologically and therapeutically. Both identified the root of all human problems as cognitive errors that needed correction.

Several Yog?c?ra notions basic to the Abhidharma phase came under severe attack by other Buddhists, especially the notion of ?layavijñ?na. Eventually the critiques became so entrenched that the Abhidharma phase atrophied. By the end of the eighth century it was eclipsed by the logic-epistemic tradition and by a hybrid school that combined basic Yog?c?ra doctrines with Tath?gatagarbha thought. The logic-epistemological phase in part side-stepped the critique by using the term cittasant?na, “mind-stream”, instead of ?layavijñ?na, for what amounted to roughly the same idea. It was easier to deny that a “stream” represented a reified self.

On the other hand, the Tath?gatagarbha hybrid school was no stranger to the charge of smuggling notions of selfhood into its doctrines, since, for example, it explicitly defined Tath?gatagarbha as “permanent, pleasurable, self, and pure (nitya, sukha, ?tman, ?uddha).” Many Tath?gatagarbha texts, in fact, argue for the acceptance of selfhood (?tman) as a sign of higher accomplishment. The hybrid school attempted to conflate Tath?gatagarbha with the ?layavijñ?na. Key works of the hybrid school include the La?k?vat?ra S?tra, Ratnagotravibh?ga (Uttaratantra), and in China the Awakening of Faith. In China during the sixth and seventh centuries, several competing forms of Yog?c?ra dominated Buddhism. A major schism between orthodox versions of Yog?c?ra and Tath?gatagarbha hybrid versions was finally settled in the eighth century in favor of a hybrid version, which became definitive for all subsequent forms of East Asian Buddhism. Yog?c?ra ideas were also studied and classified in Tibet. The Tibetans, however, tended to view the logic-epistemological tradition as distinct from Yog?c?ra proper, frequently labeling that Sautr?ntika instead. Among others, who have made significant contributions to the development of Yog?c?ra is, Sthiramati. He is opposed to have written commentaries on Vasubandhu’s eight works on

idealism. Thus with Sthiramati the first phase of Yog?c?ra idealism comes to an end. It is said that here onwards the main interest of the philosophers shifted from metaphysics to logic and epistemology and there started a new school of philosophy, which is generally known as Vynanavada. Dign?ga and Dharmak?rti are the two important names that have contribute a lot to Buddhist logic through their works. This was the second phase in the development of Buddhist idealism. The first phase of pure idealism, represented by Maitreya-Asa?ga, Vasubandhu and Sthiramati, can be called Yog?c?ra school, the second phase of idealismcum- critical realism, presented by Dign?ga19 and Dharmak?rti20, can be called Vijñ?nav?da school and the whole development, the Yog?c?ra-Vijñ?nav?da. Among these works, Dign?ga had contributed the most important works is Pram??asamuccaya. Which primarily deals with Buddhist logic. Dharmak?rti is his pupil, who has written an important work known as Pramanavartika. His celebrated work is commentary on Pram??asamuccaya. Morever, Dharmak?rti has written Nyayabindu, Pramdnauiniscaya, Hetubindu and the Sambandhapanksa and Vadanyaya. After this there emerged two important Buddhist philosophers are Santaraksita and Kamalasrla. Therein we find out another interesting development of Mah?y?na philosophy. It is said that among the two, Santaraksita tried to present a synthesis of the M?dhayamika and the Yog?c?ra systems. After this it is believed that there were no worthwhile doctrinal developments in the Yog?c?ra system.

2.2 ?rya Asanga, Vasubandhu: Life and Works 2.2.1 Asanga and his works

Arya Asa?ga is very prominent and dominating thinker in the development of Vijñanavada philosophy. He is a disciple of Maitreyanatha. Asa?ga attributed a portion of his

writings to Maitreya (the Future Buddha living in Tu?ita Heaven). Some modern scholars have argued that this Maitreya was an actual human teacher, not the Future Buddha, but the tradition is fairly clear. After twelve years of fruitless meditation alone in a cave or forest, during a moment of utter despair when Asa?ga was ready to quit due to his abject failure, Maitreya appeared to him and transported him to Tu?ita Heaven where he instructed him in previously unknown texts, Yog?c?rin works, that Asa?ga then introduced to his fellow Buddhists. Precisely which texts these are is less clear, since the Chinese and Tibetan traditions assign different works to Maitreya

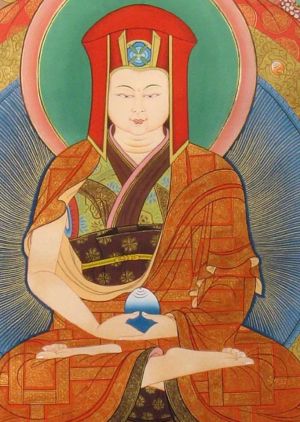

Arya Asanga (315-390)22 lived in Gandhara (modern Kandah?ra in Afganisthan) but his birthplace is Purushapura (Peshawar). He was born in a Kushika Brahmana family in the kingdom of Gandh?ra. The scholars have neglected Asa?ga for a long time. His brother Vasubandhu has clouded him though traditionally it is believed that Asa?ga was the original propounded of the Yog?c?ra School. All these accounts may be the reason why modern scholars believe that Maitreyan?tha propounded the Yog?c?ra thought. Along with his two brothers he was converted to Sarv?stiv?da School of Hinay?na Buddhism, which could not give his spiritual mind any solace.

Asanga’s important work of building Viharas, writing numerous treatises, and instructing countless monk disciples all of which was instrumental in reviving the Mah?y?na. But history remembers him chiefly for his role as founder of a new school of Mah?y?na Buddhism, the Yog?c?ra. Asanga’s School continued to emphasize meditation and the practice of Yoga as central to the realization of Bodhi or enlightenment. Later, this school underwent certain changes, becoming known first as the Vijñaptim?tra called “consciousness-only” and then, the

Vijñaptim?trav?da “representation-only” school), owing to the popularization of Asanga’s teaching through the independent works of Vasubandhu and later doctors of the lineage. Maitreyan?tha then initiated him24 in the “?unya” doctrine of Mah?y?na. He mastered the spiritual contemplation and was called S?ryaprabh?s?madhi. With this he could understand the essence of all the texts of the Great vehicle.

Tharanatha has stated that Asa?ga was one of the sons of the Brahmana matron who was married to a member of the Kshatriya community. Hiuen-tsang has also mentioned the fact that original birthplace of Asa?ga was Gandh?ra but he goes on, without modification, to change the scene of the legend and transports it to Ayodhya.

After receiving spiritual enlightenment from Maitreyan?tha, he resided in a monastary in Dharm?nkura ara?ya, a place near Magadha. Then he migrated to U?mapura vih?ra at Sagari and succeeded in bringing king Ga?bhirapaksha in to the fold of his doctrine. Towards the end of his life, he remained for twelve years at N?land? and he passed away in R?jagraha where his disciples erected a monument in his honour. According to Dr. Bagchi “Asa?ga was alive and active in the fifth century A.D.”. He gives Professor Levi’s opinion that the probable date could be the first half of fifth century and Dr. Wintemitz’s opinion that he “probably lived in the 4th Century and was originally an adherent of the Sarvastivada School”.

Mr. Bagchi in his introduction to Mah?y?nasutr?la?k?la has referred to the legend that “Asa?ga ascended the Tu?ita heaven for receiving enlightenment on the mystery of the Great vehicle from the Bodhisattva Maitreya who used to reside in that blessed region. Furthermore it has been placed on record that Asa?ga, during his sojourn in that celestial abode received Yog?c?rabhumish?stra, Mah?y?nasutr?la?k?ra, Madhyanta and other sacred texts from Maitreyanatha. Taranatha has recounted the self same classical episode, with certain modifications and has reiterated that Asa?ga mastered five teachings of Maitreya by staying in the Tu?ita heaven”.

Again Mr. Bagchi has given two opposite views regarding the authorship of this great work. He has quoted C. Tucci from his article entitled “On some aspects of the doctrines of Maitreyan?tha and Asa?ga”. G. Tucci has furnished fresh arguments to prove that Maitreyan?tha is the author of the MSL.

Asa?ga has been attributed with the authorship of MSL. He is one of the great masters of Mah?y?na Buddhism, though there are some differences of opinion about the authorship of MSL among the scholars. Asa?ga is the author of this great book that gives us briefly all the important tenets of Mah?y?na Buddhism. He has observed that the authorship of the K?rik? portion of the six treatises belongs to Maitreya and his disciple Asa?ga composed commentaries on those works.

E. Obermiller has held the view that the five works25 attributed to Maitreyan?tha by the Tibetan tradition were actually composed by Asa?ga and that the classical story of revelation of them to Asa?ga by Maitreya in Tu?ita heaven is intended to give a divine sanction to the works. The colophon of the work reveals that the original text has been announced by Bodhisattva Vyavadatasamaya. This was translating into Chinese and Tibetan. But the real identity of Vyavadatasamaya is not really known.

Buddhist scholars almost unanimously characterize the Yog?c?ra as being school of Buddhist idealism. Asa?ga’s works were aimed at correcting the mistaken views held by many Buddhist adherents of his day concerning the true meaning of the Mah?y?na scriptures. To be sure, the single, most misunderstood doctrine taught by these texts was that of sunyata, “voidness” or “emptiness.” 26 The principle of Mah?y?na is the perfection of knowledge. When the Madhyamika School propagated the doctrine of “??nya” (Void) doubt was created in the minds of people and there was controversy about it. Asanga renewed his effort to propagate Buddhism and his “Vijñanavada” was the result. So “Vijñanavada” was a doctrine that could satisfy people mentally as well as spiritually. Asanga searches for the principle of his doctrine through “Yog?c?ra”. Time was also favorable for Asanga.

These are the fundamentals from which Asa?ga has deviated in his system. He is only concerned about explaining the “mind” and the reason of existence by arrangement or interpretation. In fact Asa?ga has taken the knowledge of these ten “Bhumis”, by Bodhisattvas as granted. In shortly, the principal works of Asa?ga are:

a) Abhidharmasamuccaya: Asa?ga explains the principal doctrines of the Mah?y?na following the method already employed by the Abhidharma treatises of the Hinayana. He analyzes the dharmas and their different kinds, the Four Noble Truths, the Nirvana, the Path, the diverse kinds of individuals, the rules of debate, etc. In this treatise there are some references to cittamatra, the three characteristics of being (parikalpita, paratantra and parini?panna).

b) Mahayanasamgraha: This treatise is a summary work of the doctrines of the Yogacara School. In a clear and complete way it deals with the principal themes of this school,

giving them their canonical expression: the (names, characteristics, demonstration, kinds, moral nature); the three natures (definitions, relations, subdivisions), the Vijñaptim?tra and the inexistence of the external object; the three bodies of the Buddha. c) Yog?c?rabh?mi ??stra: This treatise is generally considered as the magnum opus of Asa?ga, although in some sources it is attributed to Maitreyan?tha and even it has been thought that it is a compilation work composed by several Yog?c?ra authors. It is a voluminous work. It comprises five major divisions of which the first, called Da?abh?mikas?tra, is the most important one. At its turn this first part contains seventeen sections, which describe the stages (bhumi) that are to be passed through by the follower of the Mah?y?na in order to reach the ultimate goal, the Nirvana also the achievements he attains in each stage. The doctrine of the alayavijñana is mentioned in this treatise.

d) Commentary on the Samdhinirmocanasutra e) Commentary on the Vajracchedika Prajnaparamitasutra

2.2.2 Vasubandhu: The Date of Problem and His Works

Vasubandhu (320-380)27 (Sanskrit; traditional Chinese: ??; Vietnamese: Th? Thân), the Buddhist philosopher, is one of the most prominent figures in the development of Buddhist philosophy in India. He is one of Indian Buddhism’s “six jewels”, “the writer of a thousand treatises”28. Therein the question was one or two or more Vasubandhu may be very important. The problem of when this philosopher lived never ceased to be controversial; numerous attempts have been made subsequently to settle it without any definite result. Therefore, we now face with not only the question of when Vasubandhu lived, but also with the problem of

how many Vasubandhu in the history of Indian philosophy. However, we are comparatively well informed as regards the great philosopher, and a determination of his date, which will contradict many sources to say about his times, is manifestly possible.

Vasubandhu’ life are know from several biographies in Chinese and Tibetan. The earliest of which is the Chinese rendering of the life of Vasubandhu by Param?rtha29, who composed it while he has been in China. However, there was apparently a previous account by Kumarajiva, which has not survived. The earliest Tibetan biography available to me is a good deal later, that of Buston. In addition, there are several references to Vasubandhu in the works of Hsuantsang and other writers. According to Chinese historical source, there are at least three different dates in which Vasubandhu might have been born: at 900 years after the Buddha nirv??a (B.N.), at 1000 B.N. or at 1100 B.N. The name of Vasubandhu has been associated in the history of Buddhist thought with a great work of Hinay?na systematics.

E. Frauwallner may have spearheaded the “two Vasubandhu” movement with his 1951 paper, “On the date of the Buddhist Master of the Law Vasubandhu.”30 Therein, he presented the argument that there was “Vasubandhu the Old” (320-380 BCE) and “Vasubandhu the Young” (400-480 BCE). The former is said to be brother to Asa?ga, who was first a member of the H?nay?nist Sarv?stiv?da-Vaibhashika Buddhist sect before converting to Mah?yana Buddhism under his brother’s influence. He wrote also numerous works of Mah?y?na inspirion. Vasubandu died before his brother Asa?ga, probably around 380A.D31. The origins of the latter alleged figure are shrouded in mystery; this Vasubandhu is also said to have been a member of the Sarv?stiv?da sect, but followed the Sautr?ntika doctrines before his conversion. Vasubandhu (The Younger) was born around 400 A.D. Nothing is know about the place of his birth and about his family. He belonged to the Sarv?stiv?da sect but gradually he became

more attached to the Sautrantika’ doctrines. One of his masters was Buddhamitra. He was protected by King Skandagupta Vikramaditya of the Gupta dynasty (455-467 A.D)32. He was invited to the royal court in Ayodhya by Baladitya and received from him many honor. He is said to be author of the ADK and Paramarthasaptatika (a refutation of the S??khya school). In contrast, Tola and Dragonetti recount the traditional view in which Asa?ga’s brother is the sole Vasubandhu, who authored the ADK while a young member of the Sarv?stiv?da- Vaibh??ikas, in addition to the Yog?c?rin works considered in this project33.

According to Param?rtha, Vasubandhu was born in Puru?apura, present-day Peshawar, in what was then the Kingdom of Gandh?ra, around the year 316 A.D34. But, according to Le Manh That, both the Chinese and Indian data give us Vasubandhu died around 395 C.E. at the age of 80. Thus he was born around 315 C.E in a Brahmin family.35 He has an elder brother, the famous Asa?ga, and the younger one by the name Viriñcavatsa. All three brothers became Sarv?stiv?da Buddhism.36 This school was still a stronghold in Gandhara, According to T?r?n?tha, Vasubandhu was born one year after his elder half-brother Asa?ga, who became a Buddhist monk. Asa?ga became the preeminent expounder of Yogacara synthesis of great of Mah?y?na Buddhism. From the internal evidence of his works, Asanga have studies mainly with scholars of the Mah???saka School. Which denied the Sarv?stiv?da existence of the past and future, and which posited a great number of “ uncompounded events”. While learning with the Mah???saka, Asa?ga came into contact with the Prajnaparamitasutras of Mah?y?na Buddhism, which was completely overturning the older monastic Buddhist ideal in favor of a life of active compassion to be crowned by complete enlightenment. Not being able to understand them, and not gaining any insight into them from his teachers, he undertook lonely forest-meditations. After twelve years of meditation, he had gained nothing. Therefore,

he decided to give up seeking enlightenment. At that moment, the Bodhisattva Maitreya stood before him and dictated five works to Asa?ga. Maitreya has revealed by writing some texts him and transmitting the so-called “ five treatises”. Asa?ga went on to write many of the key Yog?c?ra treatises such as the Yog?c?rabh?mi??stra, the Mah?y?nasa?graha and the Abhidharmasamuccaya as well as other works, although there are discrepancies between the Chinese and Tibetan traditions concerning which works are attributed to him and which to Maitreya 37 . Asa?ga became the systematic of Idealist Buddhism: Vijñaptim?tra (representation only) or Cittam?tra (mind only). However, Buddhist learning flourished in Kashmir and Bihar, among other places. Some of whose doctrines were so near to those of the Mah?y?na that when Asa?ga converted to the “Great Vehicle”. He was readily able to complement his former beliefs with the profounder insights of the Mah?y?na Sutras. When he was advance in years, Asa?ga became worried about his younger, Vasubandhu. Asa?ga encouraged Vasubandhu to enter the Mah?y?na as well, and the latter also believed that conversion did not require him to renounce any of his previous Hinay?na convictions. Vasubandhu produced the final synthesis of Hinay?na thought, then converted to Mah?y?na and assisted his brother in the latter’s own systematic endeavors, as for Viriñcavatsa, we know nothing of his activities, intellectual or otherwise.

In his youth, Vasubandhu may have received from his father much of the Bramanical lore so obviously at his command, and it may be from him also that he was introduced to the axioms of classical Nyaya and Vaisesika, both of which influenced his logical thought38. In the meantime, Vasubandhu has joined into the Sravastivada Order, and studied primarily the scholastic system of the Vaibh??ika. However, it grave doubts about the validity and relevance of Vaibh??ika metaphysics started to arise in Vasubandhu. Perhaps through the

brilliant teacher Manoratha, who had contacted with the theories of the Sautr?ntika. That Buddhists who would like to reject everything that was not the express word of the Buddha. They held the elaborate constructions of the vibhasa up to ridicule. The Sautr?ntika tradition in Purusapura is likely strong in view of the fact that. It was the birthplace of threat maverick philosopher of the second century.

Vasubandhu’ Works

Vasubandhu lived his life at the center of controversy, and he won fame and patronage through his acumen as an author and debater. His writings are an unparalleled resource for understanding the debates alive between Buddhist and Orthodox Schools of his time. Vasubandhu’s first great works the ADK. Though it is written from the standpoint of the Sarv?stiv?da School, with the Sautr?ntika polemics against it, it is nevertheless an authority for all school Buddhist philosophy. Vasubandhu composed the verses of the ADK while teaching in the city of Purusapura (Peshawar), where he had gone after escaping from the confines of Kashmir. According to Paramartha, each verse was engraved in copper, and the entire collection was sent back to his former teachers for their response. Since they agreed with the substance of the verses, they requested a commentary. At that point it became evident that Vasubandhu had embraced the Sautr?ntika point of view against the Vaibh??ikas and the reaction of the latter was a vigorous repudiation of the work and its author (Anacker 1984: 16- 18).

Recognizing that the ADK undermined the Vaibh??ika system, Sanghabhadra sought to engage Vasubandhu in debate late in life, after he had embraced the Mah?y?na approach first articulated by Asa?ga. Vasubandhu declined to debate. Therefore, Sanghabhadra produced

two works of refutation, the Nyaydnusara (Accordance with Logic) and the Abhisamayapradtpa (The Lamp of Clear Understanding). Vasubandhu had by that time little interest in defending a system that he had long since superseded in his own practice of Buddhist wisdom.

Vasubandhu composed works from the perspectives of several different philosophical schools. His works has trained and represented in the Vaibhashikas or Sarvastivadins of Kashmir and Gandh?ra, the Vatsaputriyas, the Sautr?ntikas, and the Yogacarins. Vasubandhu’s works have often been written either from the Sautrantika perspective or from the Yog?c?ra perspective. Dissatisfied with those teachings, for this reason, he wrote a summary of the Vaibh??ika perspective in the ADK in verse and an auto-commentary, the Abhidharmako?abh?sya, which summarized and critiqued the Mahavibh?sa from the Sautr?ntika viewpoint.

A great number of texts of the Therav?da Abhidharma tradition are in P?li and Sarv?stiv?da Abhidharma texts exist in the Chinese translations. Vasubandhu wrote in Sanskrit, but many of his works are known from their Chinese and Tibetan translations. The purposes of this essay to summarize all of the works attributed to Vasubandhu. He composed a number of voluminous treatises, especially on Yog?c?ra doctrines. Vasubandhu’s most important works:

1. Abhidharmako?ak?rik? (Treasury of the Abhidharma) 2. Abhidharmako?abh??ya (Commentary of the Abhidharma) 3. Vi??atik?k?rik? (the Twenty Verses) with its Commentary (Vi??atik?v?tti), 4. Tri??ika (the Thirty Verses) 5. Trisvabh?va-nirde?a (the Three Natures Exposition)

The majority of the arguments discussed below are taken from these works. Vasubandhu also wrote a large number of other works. He also contributed to Buddhist logic and the origin of formal logic in the Indian logic-epistemological tradition. Vasubandhu was particularly interested in formal logic to fortify his contributions to the traditions of dialectical contestability and debate. Anacker holds that:

“A Method for Argumentation (V?davidhi) is the only work on logic by Vasabandhu which has to any extent survived. It is the earliest of the treatises know to have been written by him on the subject. This is all the more interesting because V?da-vidhi marks the dawn of Indian formal logic. The title, "Method for Argumentation", indicates that Vasabandhu's concern with logic was primarily motivated by the wish to mould formally flawless arguments, and is thus a result of his interest in philosophical debate”

1. The Explanation of the Establishment of Action (Karmasiddhiprakara?a). 2. The Explanation of the Five Aggregates (Pañcaskandhaprakara?a) 3. The Rules for Debate (V?davidhi)

Vasubandhu is our leading author of the source texts of Yog?c?ra theory and practice. Other major authors were his elder brother Asa?ga, and Asa?ga’s teacher Maitreyan?tha. Vasubandhu’s chief disciple Sthiramati also wrote several texts in the form of commentaries on his master’s works. Vasubandhu’s commentaries on major Yog?c?ra works wrote a number of commentaries on Buddhist scriptures.

1. Dharmadharmat?vibh?gav?tti (Distinguishing Elements from Reality) 2. Madhy?ntavibh?gabh??ya (Distinguishing the Middle from the Extremes) 3. Mah?y?nas?tr?la?k?rabh??ya (The Ornament to the Great Vehicle Discourses) 4. Mah?y?nasa?grahabh??ya (The Summary of the Great Vehicle)

5. Vy?khy?yukti (The Proper Mode of Exposition) 2.3 Historical Problems of Yog?c?ra

The Tibetan viewpoint presents Asa?ga and Vasubandhu as half brothers; they shared the same mother, but had different fathers. They both came from Peshawar, but while Asa?ga was ordained in the Mah???saka Order. The younger brother Vasubandhu was ordained at Nalanda in central India and became a monk of the Sarv?stiv?da Order. He wrote a work on the “four oral traditions of Vinaya.” He then transferred to Kashmir where, under Acarya Samghabhadra, he became a scholar of the Abhidharma, eventually composing an encyclopedic work known as the ADK. Sanghabhadra opened his frontal attack upon the ADK, Vasubandhu’s other works have undergone similar critical treatments. Vasubandhu’s philosophy is presented either based exclusively upon the ADK or exclusively upon his other writings such as the Vi??atik? and the TSK40. At first Vasubandhu opposed his brother Asa?ga’s position, even writing a number of anti-Mah?y?na texts, but later he changed sides and it was from then on that he composed the famous works that teach Yog?c?ra under his name. Thus, after Asa?ga passed away, Vasubandhu assumed his brother's role as Abbot of Nalanda, where he taught his four leading students: Sthiramati, a leading teacher of Metaphysics (Abhidharma); Dignaga, the exponent of Logic-theory (Pramana); Gunaprabha, excellent in monastic Discipline (Vinaya); and Vimuktasenaa scholar of transcendental wisdom (prajna-paramita).

If Vasubandhu writes the ADK, the question is not what leads him to write it and why, but whether or not he is correct in presenting the system, which he is said to present. We should

finds some fragmentary studies on one or a series of two or three of this works together, designated as Vasubandhu’s philosophy and the like without any substance41. There are some serious problems with the account. The ADK is very different in style and composition from the Yog?c?ra works of Vasubandhu, let alone the Abhidharmako?abhasya, which is a refutation of the former. It becomes evident that Tibetan historians cobbled together a variety of fragments related to several different authors all having the name Vasubandhu. When the original fragments are sorted through, we find one Vasubandhu being the contemporary of one Indian king, and another being the contemporary of another king, centuries apart.

Two works on Abhidharma exist have been written by authors called Vasubandhu. One is the famous ADK “Treasury of Metaphysics” composed in Peshawar. Another one is the Abhidharmako?abhasya composed some centuries later in Ayodhya. We know the Vasubandhu, who authored the latter, as having been the disciple of a renowned Abhidharma master named Buddhamitra, and was appointed, according to Paramartha, by King Vikramaditya of Ayodhya (the fifth century) to be tutor to the crown prince Baladitya. The author of the ADK, on the other hand, resided in Peshawar, belonged to the Kashmiri Vaibh??ika school of Sarv?stiv?da metaphysics.

Vasumitra, a disciple of Gunamitra, who in turn was a disciple of Vasubandhu, the author of the Abhidharmako?abhasya, wrote a commentary in support of the latter work. It is said that Vasumitra belonged to the Sautr?ntika School.

Vasubandhu the author of Yog?c?ra works and brother of Asa?ga, on the other hand, resided at Kausambhi and was contemporary with King Chandragupta I, the father of Samudragupta, which places him in the fourth century.

Disregarding the author of works on monastic Discipline, at least three distinct men named Vasubandhu begin to emerge from the various historical fragments available to scholarly research. We can clearly distinguish the author of the ADK from that of the Abhidharmako?abhasya by the fact that they belong to two entirely different schools. The former is an exponent of the Vaibh??ika, teachings of the Sarv?stiv?da School, while the latter was an exponent of the Sautr?ntika.

Consequently when it is said that a certain person named Vasubandhu wrote a text supporting the philosophical outlook of one of these schools, while another wrote supporting the outlook of another school, it must be apparent that very different authors are involved, even though they carry the same name. The improbability of one Vasubandhu switching schools and composing a text in opposition to his earlier position is determined by the fact that the different authors in question were contemporary with or patronized by Indian Kings who lived in very different eras.

It therefore seems likely that at least three authors named Vasubandhu can be distinguished: First: Vasubandhu, the author of the ADK. He was a monk of the Sarv?stiv?da Order and lived in Peshawar. His leading disciple was Manoratha, and later another writer, Gunaprabha, author of the Vibhasha-sastra, was of the same line. Manoratha, as we know from his own works, was a confirmed follower of the author of the ADK. He apparently knew nothing of the

counter Abhidharmako?ahasya, which he certainly would have known had his teacher been the author of it.

Second: Vasubandhu, the brother of Asa?ga and the author of various works on Yog?c?ra. Who lived in Kausambhi circa 290-370 Abhidharma. He was a contemporary of King Chandragupta I and Samudragupta. His leading disciple was Sthiramati, and a later descendant of this lineage was Gunabhadra, who traveled to China in c. 430 Abhidharma. We know from the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang42 that when he visited India in the seventh century, there could still be seen, in the Ghositarama of Kausambhi, the ruin of the old house where, in an upper chamber, Vasubandhu composed his famous Yog?c?ra treatise, known as the “Thirty Verses on Perception” (Trimsikavijnaptikarika). Hiuen Tsang also places Acarya Dharmapala, a later follower of Vasubandhu’s lineage, in Kausambhi.

Third: Vasubandhu, the author of the Abhidharmako?abhasya, who lived in Ayodhya (Saketa). He was a Sautr?ntika and contemporary of King Vikramaditya (455-467 AD). His disciples were Gunamati, Vasumitra and the renowned logician Dign?ga. Gunamati taught a pupil called Sthiramati who was a contemporary of King Darasena I (c. 460 AD) of Valabhi, and thus not the same as the Yog?c?ra author by the same name. Both Gunamati and Vasumati, from their writings, appear as staunch supporters of the Bhasya, as opposed to the ADK itself or, for that matter, the Yog?c?ra position. Dign?ga was the teacher of two very famous scholars, Dharmak?rti and Dharmottara.

We further find that the Yog?c?ra outlook represented by this school later divided into two distinct systems, one that we might call the orthodox position and the other a popular offshoot. The orthodox position is that held by Vasubandhu’s direct disciple Sthiramati, who advocated

what is called nirakara-vijnana-vada (the doctrine of non-substantive consciousness) based on asserting the emptiness (??nyata) of both external objects and consciousness. This view was eventually transmitted by Paramartha (499-590 AD) to China, and is the same as that held by Tilopa, the founder of the Kagyu school of Tibet, as expressed in his song of Mahamudra called the Ganga-ma. It is also the viewpoint expounded by Acarya Manjusrimitra in the penultimate Yog?c?ra treatise, the Bodhicittabhavana.

The popular or exoteric position, which appears to deviate from Vasubandhu’s original exposition of Yog?c?ra theory, is that of Acarya Dharmapala. Dharmapala systematized a line of Yog?c?ra thought known as sakara-vijnana-vada (the doctrine of substantive consciousness) that claims, although external objects do not independently exist, the mind itself (cittamatra) does exist as such. This view, which we know as Mind-only, presents Mind as ultimate reality. Dharmapala’s line of thought has transmitted to China by Hiuen Tsang, the famous Chinese pilgrim mentioned above, in the seventh century and has since had a significant impact on the practice of Zen in Japan. Huge efforts on the part of generations of Tibetan scholars have been spent attempting to demonstrate in logical terms the impractical basis of this latter doctrine.

Regardless of scholastic efforts in whatever direction, it nevertheless appears that the original position held by the illuminated master Vasubandhu, is very much that of non-substantive consciousness, or in other words, the Nirakaravijnana view expressed by his direct disciple Sthiramati. This outlook asserts that observer and observed, or in other words, consciousness and external objects, are bound together in an indissoluble union impossible of splitting apart. Nevertheless, both lack credible claim to independent ontological existence. The term that describes this union is “simultaneous arising”, which means that consciousness and its object

arise, and can only arise, in immediate proximity. Or, in other words, one cannot come into being without the other. There are logical assumptions that follow from acknowledging this condition, that lead to what in modern terms would be called quantum theories of consciousness. Apparently practitioners of Yog?c?ra grasped certain insights centuries ago, which only now are being realized by the most radical discoveries in new cosmological theory. According to tradition, Vasubandhu first studied Vaibh??ika Buddhist teachings, writing an encyclopedic summary of their teachings that has become a standard work throughout the Buddhist world, the ADK (Treasury of Abhidharma). As he grew critical of Vaibh??ika teachings, he wrote a commentary to that work refuting many of its tenets. Intellectually restless for a while, Vasubandhu composed a variety of works that chart his journey to Yog?c?ra, the best known of these being the Karmasiddhi-prakara?a (Investigation Establishing Karma) and Pañcaskandhaka-prakara?a (Investigation into the Five Aggregates). These works show a deep familiarity with the Abhidharmic categories discussed in the Ko?a, with attempts to rethink them; the philosophical and scholastic disputes of the day are also explored, and the new positions Vasubandhu formulates in these texts bring him closer to Yogacarin conclusions.

A few modern scholars have argued, on the basis of some conflicting accounts in old biographies of Vasubandhu, that these texts along with the ADK were not written by the Yog?c?rin Vasubandhu, but by someone else. Since the progression and development of his thought, however, is so strikingly evident in these works, and the similarity of vocabulary and style of argument so apparent across the texts, the theory of Two Vasubandhus has little merit. 43 The writings of Asa?ga and Vasubandhu ranged from vast encyclopedic compendiums of Buddhist doctrine (e.g., Yog?c?rabh?mi-??stra, Mah?y?nasa?graha,

Abhidharmasamuccaya), to terse versified encapsulations of Yog?c?ra praxis (e.g.,TSK, TSN), to focused systematic treatises on Yog?c?ra themes (e.g., TSK, MDV), to commentaries on well-known Mah?y?na scriptures and treatises such as the Lotus and Diamond Sutras. Since the SDS offers highly sophisticated, well-developed doctrines, it is reasonable to assume that these ideas had been under development for some time, possibly centuries, before this scripture emerged. Since Asa?ga and Vasubandhu lived a century or more after the SDS appeared, it is also reasonable to assume that others had further refined these ideas in the interim.

2.4 Why Vijñanavada Is Called Yogacara

Vijñ?na? is one of the most important technical terms in Buddhism. This Vijñ?nav?da school of Asa?ga is also known as Yog?c?ra. The basic question here is: why is this system called Yog?c?ra? Yog?c?ra means: “practice of meditation”. The earlier phase of Buddhism was quiet familiar with the Yoga terminology. Vijñ?na (P?li: viññ??a) mean as “Consciousness or awareness”, Vijñ?nav?da (Consciousness of Doctrine) is an alternate name for the Yog?c?ra school. Vijñ?na? is often translated as “consciousness” but other meanings include discernment, knowledge, judgment, faculty of knowing, and organ of knowledge, intellectual activity, and cognitive activity. It covers the responses and mental processing stimulated by all perceptual events. In both its active, discriminative form of knowing, and its subliminal or unconscious bodily and psychic functions. It is important to realize that Vijñ?na means more than the stream of mental awareness. The name Vijñ?nav?da can be reserved for this school and the pure idealism of Maitreya, Asa?ga, Vasubandhu be called Yog?c?ra. The entire system may be called, as is actually done by some scholars and historians, the system of Yogacara- Vijñanavada.44

The system is named “Yog?c?ra” is preference to the more well known appellation “Vijñ?nav?da” merely for the sake of drawing a convenient distinction. The School of Dign?ga and Dharmakirti occupices a peculiar position. They essentially accept the doctrine of Vijñaptim?tra, and the unreality of the object. However, when they enter into logical discussions, they endorse the Sautr?ntika standpoint of something being given in knowledge. Moreover, the Da?abh?mikas?tra systematically proposes ten different stages (bh?mis) of meditation (Yoga) for a Bodhisattva for an overall purification. In addition, this famous work. i.e. Lankavatarasutra (LAS) also induces the Bodhisattva to follow Yoga in order to become Mah?yogin. The school of Yog?c?ra deals with ideas, consciousness, mind in its works in a very extensive way. This school is generally known as idealism. According to this, all existence has its center and being in mind45. The Yog?c?ra believes that reality is a mere idea and the same has its center in consciousness or mind. Idealism consists in the assertion that there exist none but thinking entities. The other thing, we think we perceive in intuition being only presentation of thinking entity to which no object outside the latter can be formed to correspond. Things are given objects discoverable by our senses external to us but of what they may be in themselves we know nothing, we know only that phenomena. The presentation they produce in us as they affect our sense. The extensive usage of the Yogic terms in the works like Da?abh?mikas?tra and La?k?vat?ras?tra justifies the Vijñ?nav?da School to be rightly called Yog?c?ra46. Thus, the combined name of this system is properly designated as Yog?c?ra- Vijñ?nav?da.

For Asa?ga and others, the absolute truth, pure consciousness (Vijñ?na) can only be realized by practice of Yoga. That indicates the practical side of this school, while the word “Vijñ?nav?da” bring out its speculative features. In its practical application it is described as

Yog?c?ra, i.e., following the path of Yoga. Theses philosophers thought that ultimate reality could only be realized by yogic means, by meditation and contemplation and not by mere philosophical reasoning. This is called Vijñ?nav?da because philosophically it propagates that the ultimate reality is only pure consciousness (Vijñ?na). Looked at from the practical standpoint, in its moral and religious aspects, it is Yog?c?ra; in its metaphysical aspect, it is Vijñ?nav?da. It is already mentioned that Asa?ga’ Vijñ?nav?da is not merely idealism but absolutism. This MSL deals with his absolutistic. Here we can neither find criticism of Sautr?ntika nor of ??nyav?da like his MDV47. This work is completely dedicated to the absolutism of Vijñ?nav?da.

Maitreyan?tha, a systematic expounder of Vijñ?nav?da school of Buddhism, was also the teacher of Asa?ga. He is mainly responsible for contributing absolutism in its fully developed form to Vijñ?nav?da. He has written many works, but four are well known in the Vijñ?nav?da circle. They are Madhyantavibh?ga, Dharmadharmat?vibha?ga, Mah?y?nas?trala?k?ra and Yog?c?rabh?mi??stra. The MSL of Asa?ga is a landmark in the development of Vijñ?nav?da absolutism. Here we can see Vijñ?nav?da in it fully developed form of absolutism. In fact this is a gigantic work on Mah?y?na Buddhism. The title itself indicates its manifold features of Mah?y?na. Putting it in Asa?ga own words, it is an embellishment of Mah?y?nas?tra. There is no Buddhist topic, which is not touched by Asanga.

The school was also called Yog?c?ra because it provided a comprehensive, therapeutic framework for engaging in the practices that lead to the goal of the Bodhisattva path, namely enlightened cognition. Meditation served as the laboratory in which one could study how the mind operated. Yog?c?ra focused on the question of consciousness from a variety of approaches, including meditation, psychological analysis, epistemology, scholastic

categorization, and karmic analysis. 48 Yog?c?ra doctrine is summarized in the term vijñaptim?tra “consciousness only” which has sometimes been interpreted as indicating a type of metaphysical idealism.

The claim that mind only is real and that everything else is created by mind. However, the Yog?c?rin writings themselves argue something very different. Consciousness (Vijñ?na) is not the ultimate reality or solution, but rather the root problem. This problem emerges in ordinary mental operations, and bringing those operations to an end can only solve it. Yog?c?ra tends to be misinterpreted as a form of metaphysical idealism primarily because its teachings are taken for ontological propositions rather than as epistemological warnings about karmic problems. The Yog?c?ra focus on cognition and consciousness grew out of its analysis of karma, and not for the sake of metaphysical speculation.

To sum up, the Yog?c?ra is one of the great philosophical schools of Mah?y?na Buddhism. It had strong influence not only in Buddhist circles but also in Brahmanical currents of thought. Many persons adhered to its philosophical points of view. The Yog?c?ra produced many first class philosophers, of deep and subtle insight, systematization liability, bold inspiration, logical rigout, who raised a great, all encompassing philosophical construction of well-defined lines and firm structure. It gave rise to a huge literature, many of whose works can be considered, according to universal criteria, as philosophical masterpieces, as for instance the three treatises that this volume contains.

Yog?c?ra hold that truly, ultimately, consciousness is non-conceptual, radiant and completely pure would hence incline towards a “without-form” perspective from the point of view of the final truth, as seen by a Buddha. As ultimate, a Buddha’s radiant pure non-conceptual 46 consciousness simply cannot be stained at all by forms or images of objects. The Yog?c?ra showed a great capacity for change and self-enrichment, constantly adding new tenets to the ancient ones, refining the traditional concepts, giving more subtlety to their arguments, introducing more coherence in their classifications. A major glory of the Yog?c?ra is that it gave rise to one of the most brilliant products of Indian genius: the Buddhist school of logic and epistemology.

Besides its philosophical activity, the Yog?c?ra had also a religious interest centered around the notion of Bodhisattva, die ideal of perfected man, the moral and intellectual Path he must follow, the stages he must pass through, the goals he must reach. And in this respect the Yog?c?ra revealed the same masterly qualities that it showed in the accomplishment of its philosophical labors.

References

1 Melanie. K. Johnson-Moxley (2008), p.8. 2 Sharma.T.R (2007), p.12. 3 Ibid., p.14. 4 Melanie .K. Johnson-Moxley (2008), p.1. 5 Tola, Fernando and Dragonetti, Carmen (2004), p.19. 6 Chatterjee, Ashok .K (1971), p.54. 7 Wood, Thomas. E (1991), p.63. 8 Kalupahana, David. J (1987). 9 Kochumuttom, Thomas. A (1982), P.46. 10 Chatterjee. A.K (1975), p. vii. 11 Sharma.T.R (2007), p.4. 12 Ibid., p.5. 13 Chatterjee. A.K (1975), p. 4. 14 Ibid., p.6-7. 15 Tagawa Shun’ei (2009), p.vii. 16 Sharma.T.R (2007), p.15. 17 Chatterjee.A.K (1975), p.27. 18 It meanTreatise on the Stages of Yoga Practice. 19 Dign?ga (480 –540 CE), An Indian scholar and one of the Buddhist founders of Indian logic. 20 Dharmak?rti (c. 7th century) The Buddhist founders of Indian philosophical logic. 21 Sharma.T.R (2007), p.13. 22 Fernando Tola, Carmen Dragonetti (2004), p.xiv. 23 Asa?ga, Dr.Surekha Vijay Limaye (transl) (2000), p.xi. 48 24 According to Tibetan authorities, the works of Maitreyan?tha are four: i. Mah?y?nasutralamkara (Skt. text edited by S. Levi, Paris 1907), ii. Madhyantavibhanga (Skt. text edited by Yamaguchi, Nagoya 1934), and Dharmadharmatavibhanga (Obermiller gives a summary analysis of this work in his translation of the Uttaratantra, 1931), iii. Uttaratantra (translated from the Tibetan into English by Obermiller, Acta Orientalia, Vol. IX, 1931). iv. Abhisamayalamkara (Skt. edition by Stcherbatsky & Obermiller, BB XXII, Leningrad, Vol. I, 1929. Haribhadra's Aloka, a commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara, has been published by Wogihara, Tokya, 1932-5, and by Tucci, GOS, 62, Baroda 1932). 25 This is five works i. Yog?c?rabh?mi??tra ii. Yogavibhnga?tra iii. Mah?y?nas?tr?la?k?ra iv. Madhy?ntavibh?ga v. Vajracchedika p?ramita ??tra and saptada?abh?m 26 Janice Dean Wills (2002), p.13. 27 Fernando Tola, Carmen Dragonetti (2004), p. xiv. 28 Anacker.S (1970), p. 1. 29 Paramartha (499-569), the Indian Buddhist Monk 30 Frauwallner, E, On the date of the Buddhist Master of the Law Vasubandhu (Is Meo, Rome 1951) in Tola and Dragonetti, note 10, p.17. 31 Fernando Tola, Carmen Dragonetti (2004), p.56. 32 Ibid., p. 56. 33 Ibid., p. 55. 34 Anacker, Stefan (1984), p. 11. 35 That, Le Manh (2006), p. 60. 36 According to Paramartha, he considers that all three sons had originally been named Vasubandhu, perhaps out of reverence for a great Mah?y?na teacher of that name. 37 Giuseppe Tucci, On Some Aspects of the Doctrines of Maitreya and the Asa?ga, Calcutta, 1930. 38 Anacker. S (1984), p.13. 39 Ibid., p. 31. 40 That, Le Manh (2006), p.15. 49 41 Ibid., p.14. 42 Beal (1981), p.34. 43 That, Le Manh (2006), p. 30. 44 Mario D’amato (2012), p.6. 45 Sharma.T.R (2007), p.20. 46 Ibid., p.20. 47 Madhyantavibh?gas?trabh??yat?k? of Sthriamati, p.9-22. 48 Tagawa Shun’ei (2009), p. X.