Sems dpa, the Buddhist Spiritual Warrior, the Hero, the fearless Buddhist: overcoming self-ignorance and our maras

The term Spiritual Warrior (Tibetan “sems dpa”) may hint at more than a whiff of bravado and violence — until it is understood that the enemy of the Spiritual Warrior is “avidya” or self-ignorance. Overcoming avidya is at the root of Buddha’s teachings, and so is the conduct of the warrior spirit inherent in the term.

Buddhism — while pacificist in nature — is full of military terms — not because Dharma is violent, but because, “warrior” is a metaphor best understood by human beings. In Mahayana Buddhism, where compassion is the equal of wisdom, the concept is taken to the next level, where the warrior is also the hero rescuing others — the Bodhisattva. Then, there’s is the greatest “super hero” of all time: Green Tara; or the great Yogi hero Milarepa, who faced countless demons.

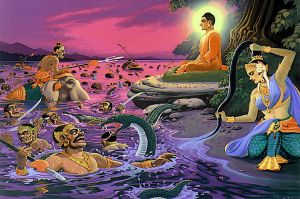

“Warrior” connotes fearlessness. Overcoming fear is a core practice in Buddhism. Green Tara, in Tibetan Buddhism, is a practice focused largely on removing fear. Equally, self-discipline is the key to successful Buddhist practice. Buddha, himself descended from warrior caste, understood the military well. When Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree, in his mission to attain Enlightenment, he faced entire armies of fears — Mara’s hordes:

“Monks, Māra, the evil one, did not pay heed to Sārthavāha’s warning. Instead, he gathered all four divisions of his great and powerful army. It was a terrifying army, so brave in battle that it would make anyone’s hair stand on end. Such an army had never been seen before, or even heard of, in the realms of gods and humans. The soldiers were able to transform their faces in

a trillion ways. On their arms and legs slithered hundreds of thousands of snakes, and in their hands they brandished swords, bows, arrows, darts, lances, axes, tridents, clubs, staffs, bludgeons, lassos, cudgels, discuses, vajras, and spears. Their bodies were covered in finest cuirasses and armour.” Fearlessness is a necessary trait of successful Buddhist practice.

For a story on overcoming Fears,

For a story on “Transforming demons”

For a story on the protections of Green Tara,

The enemy is “delusions”

Lieutenant Jeanette Shin, the US military’s first Buddhist chaplain, points out:

“Terms like charioteer, sword and shield, war elephants, banners, fortress, archers, arrows, poisoned arrows, are all used in expressing the struggle to overcome one’s delusions.” [1]

Here are just a few examples:

Conqueror — in Sanskrit Tathagata — is synonymous with Buddha: the victorious conqueror over samsara.

Sems dpa — Tibetan for “Spiritual Warrior,” synonymous with the Bodhisattvas (both the Enlightened Bodhisattvas and the Mahayana practitioners who become “bodhisattvas” when they generate bodhicitta.)

Sangha — in Pali and Sanskrit means “company” or “assembly” and is governed by precepts

Vinaya — in Pali and Sanskrit means “discipline”; also called Patimokkha (Pali) or Pratimoksha (Sanskrit.)

Daka and Dakini — translates as “Hero” and “Heroine,” the champions of the Enlightened Sangha in Tibetan Buddhism.

Protectors and Guardians — often symbolically armed with many weapons: spears, flaming swords, lassos — each carrying profound meaning.

Shaolin martial arts — in legend Bodhidharma, the great Buddhist saint, reputedly taught the monks the skills of self-defence.

Clearly, these word choices do not mean that Buddhism espouses violent behaviour — and the only “killing” going on will be that of our delusions. That fearlessness does carry over into “daily” lives, though, as explained by Lieutenant Shin, with the story of Buddha stopping the physical (non-spiritual) armies of King Virudhaka [1]:

King Virudhaka declared war against the Buddha’s clan, the Shakyas, and marched against them. The Buddha stood in his way three times. Each time King Virudhaka dismounted, paid his respects, remounted and retreated, but he kept coming back every day. Despite the warrior metaphors, Buddha was also careful to caution against the pride of victory [from the Dhammapada]:

Victory breeds hatred

The defeated live in pain,

Happily the peaceful live,

Giving up victory and defeat.

Fortitude to face Demon Valley

Imagine the lone Yogi, in a cave high in the mountains, surrounded by howling winds and wild animals and unseen dangers. Among the greatest of Yogis was Milarepa, who famously described the demons who tried to subdue him in Lachi Snow Mountains:

“When I arrived at the foot of the mountain, violent claps of thunder and flashes of lightning struck all around. The whole sky was on fire… The Lord of Obstacle-Makers … came in the guise of a Nepalese Demon called Bhairo with a vast demonic army as retinue…”

The Demons tried everything to intimidate Milarepa, with huge boulders flying through the air, rivers diverted from their riverbeds to swamp him. Milarepa subdued the flood with a simple gesture.

Whether you view the dangers as internal, or external, it takes courage to practice as a Yogi

Famously, Chogyam Trungpa wrote the book, The Sacred Path of the Warrior, in which he wrote:

“Warrior-ship here does not refer to making war on others. Aggression is the source of our problems, not the solution. Here the word “warrior” is taken from the Tibetan “pawo,” which means, “one who is brave.” … “And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly, what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

It’s fascinating that this mirrors another spiritual warrior (previously interviewed in Buddha Weekly) named Sean Walking Bear, a Cree medicine man:

“Spiritual Warfare is the battle in the mental and physical against all adversaries of the Creator. They are obstacles. They distance us from the Creator. They can attack us psychologically and biologically. They are what some may call demons, evil spirits. Their attacks are endless and last from birth to death. But, it is still possible to have peace.”

The great weapon in the Buddhist Warrior’s arsenal

In one way, it’s unfortunate, as we live in a violent, war-like reality; but that is precisely what Buddha’s teachings are focused on. Samsara is a world of suffering, and the discipline of Dharma is the best way to overcome the perils of the world. One of the great weapons in the Buddhist warrior’s is kindness, compassion and helping others. In the Abhaya Sutta, the “Fearless Sutra,” Buddha explains why the person who has “done what is good” has nothing to fear:

Buddha mentions a fearless person “who has done what is good, has done what is skillful, has given protection to those in fear, and has not done what is evil, savage, or cruel. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘I have done what is good, have done what is skillful, have given protection to those in fear, and I have not done what is evil, savage, or cruel… He does not grieve, is not tormented; does not weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.” [Full story here>> ]

Military-like code of conduct

Many other religions use military language, of course. In The hymn “Onward Christian soldiers” comes to mind. But, in Buddhism, the metaphor of soldier and warrior is pervasive, right from the original teachings of the Buddha, through to the Vinaya code of conduct, through to the various forms of Buddhism, and especially in Tibetan Buddhism and Shaolin Mahayana Buddhism.

The military-like code of conduct, the Vinaya, evokes the proper discipline and tone of the original monks and nuns of Buddha’s Sangha, as described in the Agganna Sutta. In monasteries, a high ranking monk is normally the “disciplinarian.” For lay practitioners, we had only five core moral precepts — not to kill, steal, lie, become drunk or high, or abuse sense-pleasures (to use modern language). But, in personal practice, we are our own disciplinarians.

Refraining from killing remains a key precept. But the activities of the Buddhist practitioner, working with the “demons” and internal obstacles of craving, doubt and anger, remains a warrior-like mission. Even in simple breathing meditation, military-like discipline is needed.

Missed a meditation session? Impose a hundred metaphorical laps around the stupa as a self-imposed discipline. Craving a new luxury car? Sit, and meditate on the attachment — and how that money could benefit so many others. Lied to a friend? Come clean, then promise not to do it again. In moral conduct, an even more rigorous “military” code — the precepts of the Buddha — makes sure the spiritual “soldier” focuses on compassion and wisdom, and ultimately, Enlightenment.

There are two key differences between the spiritual warrior and the actual weapon-brandishing warrior: spiritual warriors fight obstacles and delusions, and do not kill sentient beings; and the discipline is self-imposed. You are the hero, general, and soldier. You answer only to the Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma and the Enlightened Sangha. The Enlightened Sangha of spiritual heroes is our example.

Moral dilemmas of a soldier

Buddhists face the same dilemmas and tough choices as a soldier with a gun. The soldier might have enlisted to save lives, to stop terrorism, to protect his nation — all positive motivations — and any killing would be in defence of innocents. They may take on the karma of the killing, but may still feel morally vindicated by the lives they saved. In the same way, a lay Buddhist might face tough choices such as:

White lies to avoid unnecessary suffering of another (some truth that might be devastating to the person hearing it) Euthanasia issues, to eliminate one kind of suffering for the terminally ill pet, for example, is against the precept of killing — but often we take on that negative karma for the sake of our beloved, suffering pet.

Killing in self-defence — a similar situation to the working soldier with a gun who is defending the innocent from harm.

In other words, like real soldiers, the Buddhist must make daily decisions with repercussions. The real soldier relies on the chain-of-command to justify actions. The Buddhist spiritual warrior relies on Buddha, Dharma and Sangha — and ultimately, the self.

Shakyamuni Buddha, born to “warrior caste”

When Shakyamuni Buddha cut his hair, he symbolically separated himself from the worldly, including his past role as a princely member of the “warrior caste.” The Shakya clan — to which he was the heir — was a warrior caste governed state, at a time when the warrior caste and the brahminic caste were rivals for leadership. He was an expert He put aside all of that, and instead

marched to war against Mara and his demons. You can view Mara as a literal devil-like being, or as our own mind’s temptations born of our cravings and self-ignorance (Sanskrit: avidya.) Either way, when Buddha determined to release the world from the suffering of Samsara, his mission became a mental crusade. In the final “battle” he sat beneath the Bodhi Tree, fighting with Mara and his demons and daughters (temptations) until he attained final, and complete victory.

Buddha and the demons

Confronted by the demons, according to the Lalitavistara Sutra:

Yet the One Who Has Qualities, Marks, and Splendor

Keeps his mind unshaken, like Mount Meru.

He sees all phenomena as illusion,

Like a dream, and like clouds.

Since he sees them in this manner that accords with the Dharma,

He meditates steadfastly, established in the Dharma.

Whoever thinks of “me” and “mine”

And clings to objects and the body,

Should be afraid and terrified,

Since they are in the clutches of ignorance.

The Son of the Śākyas has realized the essential truth

That all phenomena arise in dependence and lack reality.

With a mind like the sky, he is just fine,

Unperturbed by the spectacle of the army of rogues.

One by one the “sons” of Mara try to bring down the great Bodhisattva. One tries to enter his body and destroy him from within — possession — another tries to poison him with a “gaze than can turn the waters of the ocean to ashes”, and another sends “divine girls”, an exquisite harem. But, even the demons realize the futility. Dharmarati says:

“He only delights in the pleasures of the Dharma,

The bliss of concentration and the significance of immortality,

And the joy of liberating sentient beings and the happiness of a loving mind.

He does not delight in the pleasures of passion.”

Ultimately, the greatest torment, the vilest image, the most bloody of threats, and the most exquisite of beauties cannot move Siddartha’s mind. In the end, they send their entire army against the Buddha, but the result is a rain of flowers, as reported by Bharasena, the general of the demon army:

“Wherever this army is found,

Dust and soot rain from the sky.

Yet at the seat of awakening, a rain of flowers falls,

So heed my words and turn back!”

NOTES

[1] “The Buddha as Warrior” Lieutenant Jeanette Shin. https://www.wildmind.org/blogs/on-practice/the-buddha-as-warrior

Source

[[1]]