The third precept: avoiding sexual misconduct

Written for the AQA syllabus by Robert Ellis, formerly a member of the Triratna Buddhist Order and a former Head of RS in a 6th-form college.

I undertake the rule of training which consists in abstention from sexual misconduct

The third precept could be literally translated as avoiding sensual misconduct (Pali: kamesu micchacara “in the sensual desires bad actions”). This means that some Buddhists (e.g. Sangharakshita) claim that it is not only concerned with sexual desire, but also other kinds of sensual desire. On this interpretation the third precept would involve avoiding eating too much chocolate as well as sexual misconduct. Others (e.g. the early Theravada commentator Buddhaghosa1) insist that it is only concerned with sexual misconduct, and certainly sexual misconduct is always the main focus of discussion of this precept.

The ultimate ideal in Buddhism is to go beyond sexual differentiation, because our attachment to being male or female, and the specific feelings this brings with it, is part of what holds us back from developing towards enlightenment. This is best achieved by avoiding sexual activity altogether, so the best practice (for those in a position to follow it) is celibacy, as practiced by monks and nuns. Sometimes temporary celibacy for a limited period is also followed by lay people, and in the Theravada this is one of the eight precepts that lay people sometimes take temporarily. However, if one is an adult lay person, the expectation in a traditional society is that one will be married, and thus not in a position to practice celibacy. The best alternative is to keep one’s sexual activity within certain moral bounds by avoiding sexual misconduct.

Interpretations of the precept

Minimally this means the avoidance of rape, abduction and adultery. So if one is married (and in the modern West, this is often taken to mean in any kind of settled sexual relationship) it would be a breach of the precept to have sex outside that relationship, or to have sex which involved violence (which would also be a breach of the first precept). There is more controversy over fornication (casual sex before marriage) and over homosexuality. Here there is a great gulf in attitudes between traditional Theravadins, who tend to be very conservative on sexual morality, and modern Western Buddhists, who tend to be liberal. Tibetan Buddhists are probably in between, as traditional Tibetan culture is relatively liberal about sex.

Buddhaghosha, in his commentary written in Sri Lanka about 400 C.E.(see Buddhist Scriptures p.71-72), provides a very conservative interpretation of the precept (entirely oriented towards men) forbidding homosexuality and sex with twenty categories of women, which seems to effectively rule out most possible sex outside marriage.

Sangharakshita, giving a modern interpretation for Western Buddhists, sees the third precept as being about avoiding sexual activity which is exploitative in any way or hurts others. This means it would be unethical to have sex with someone else's wife or husband if this is likely to upset them, just as it would be unethical to have sex with someone else's boyfriend/girlfriend where this would have bad effects. Sangharakshita has no problem with homosexuality, and indeed at times has been accused of favouring homosexuality over other forms of sexuality.

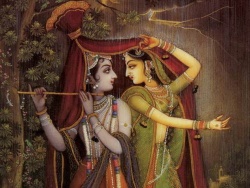

In practice attitudes to sex vary enormously between different Buddhist cultures. For example, in some parts of Tibet polyandry (one woman having several husbands) has been freely tolerated. In others Buddhism is used to support a strong condemnation of homosexuality that seems to be largely cultural. In the Tantra (Vajrayana form of Buddhism) in ancient India, there were some advanced meditation practices that involved sexual coupling whilst in a deeply absorbed meditation state, visualising one’s partner as a dakini (a symbolic deity). Again this has been tolerated within certain very restricted circumstances.

The positive counterpart of the negative form of the third precept is the cultivation of stillness, simplicity and contentment. This shows the close relationship between the underlying values of the third precept and meditation. It is one’s mental state that might drive one into unskilful sexual relationships, for example. Meditation practice can help in cultivating contentment with whatever one’s position is, whether celibate, single, or married. It also suggests that a lack of contentedness with other things (e.g. with one’s possessions) may have similar roots to sexual craving.

Discussion and evaluation

Do you agree with the view (a widespread Buddhist view) that sex is always the result of unskilful mental activity rooted in greed? If so, how is it best to respond to this: through practicing celibacy, through the institution of marriage, or by just trying to avoid the most obvious forms of sexual misconduct?