Tsu-Do Zen by Charles Carreon

I have had this idea for a long time now -- at least a year. I think it's done.

What I would like to propose is something I call Tsu-do Zen, because it looks better than PseudoZen. People might think it was fake or something.

Tsu-do could mean something like "self-so-way," as "Tsu-jan" means "Self-so-ness."

So Tsu-do Zen would be "self-so-way meditation."

If all of this sounds something like Zen, you're catching on. You see, it sounds like Zen, but it isn't.

It isn't because I'm not Japanese.

If I were Japanese, or Gary Snyder, I could claim it was Zen, say I studied at Eiheiji or in someone's backyard in Kyoto.

But I studied in someone's backyard in Tempe, Arizona, so whatever I'm saying, it's not Zen.

However, I believe that fair and impartial study will determine that Tsu-do Zen can cause effects virtually indistinguishable from Zen itself, when applied to the same subject group.

Double-blind testing could be arranged, with a placebo group. Three equal groups of American Buddha Board posters could be chosen at random, and exposed to the teachings of Zen, Tsu-do Zen and television (the placebo).

Opportunities for silent meditation would be provided to all three.

Tsu-do Zen students would be told that theirs was an honorable and established tradition from the East (New Jersey).

Their meditation teachers would also wear dark robes and speak little. Some of them would hit you with sticks, cryptically bowing after administering the punishment.

After ten days, their conditions would be compared. Donations would be solicited to continue the work.

If the meditators jointly raised as much as the TV watchers spent on home-shopping network we could arrange a merger between the two sects.

The Mood of Tsu-do Zen

From what I can tell Zen monasteries are quiet, tidy places With rocks, pine trees, pine needles, puddles of water and frogs, Etcetera etcetera, Hot bowls of noodles, smooth wood, Chopsticks, Bald people, Black clothing.

Let’s just pretend that’s the mood of Zen.

The mood of Tsu-do Zen might be similar. But without the bald people.

The mood of Tsu-do Zen might be Cool Outrageous Simpatico Absurdo Rock and roll Devil may care Sincerely swear Out of there No one cares

And then it might be just Water dripping in a mossy bucket Tiny ripples in a small circle of cold water.

The mood of Tsu-do Zen might Adapt to circumstances And thus seem to show grace, But it would just be Tsu-do Zen No big deal

The mood of Tsu-do Zen Is delicate to establish.

Applying the same care And similar methods From the Zen repertoire, Similar results might be achieved.

The Practicioner of Tsu-Do Zen rejects all recognition. If someone insists that the Tsu-Do Zen practicioner is indeed a practicioner, it is permissible to yell at that person, and threaten to call the police.

The Practicioner of Tsu-Do Zen chastises him or herself for attempting to practice. Any attempt to ascertain correct practice would be an assertion that there is a true, knowable path, and thus would be a Tsu-Do Zen heresy, if there were such a thing. But of course, there is not. Imitation of Zen is the only safe approach, while always remembering that it is merely an imitation, and cannot be the "real thing."

The Practicioner of Tsu-Do Zen has no attainment. While other paths, including Zen, make this claim, even about the Buddha himself, Tsu-Do Zen delivers. The Tsu-Do Zen practicioner actually attains nothing more than a simulated experience resembling that of Zen.

The Practitioner of Tsu-Do Zen does not doubt the way of Tsu-Do Zen. There is nothing to doubt in Tsu-Do Zen, because everything that is asserted is self-evident. Because it does not maintain that things are such-and-so, there are no contentions to adopt, and no opposition to them. Thus, faith is not required. If faith is not required, there is no room for doubt. Thus, the way of Tsu-Do Zen is unassailable.

The Practicioner of Tsu-Do Zen experiences the human condition. Because the way of Tsu-Do Zen provides no insulation from the pain of life, aside from the brief comfort of the similar-to-Zen sense of calm and serenity, the Tsu-Do Zen practicioner suffers right along with the rest of humanity, and cherishes no hope of relief.

The Practicioner of Tsu-Do Zen has no gospel of salvation. Without doctrines or status as a spiritual authority, a Tsu-Zen practicioner is poorly equipped to save others. Apparently, he is unable to save himself. While open to the possibility of salvation, as to all other possibilities not blatantly absurd, the Tsu-Do Zenner does not perform the disservice of offering a placebo or untested remedy. A Tsu-Do Zenner does not offer his guests what he has not himself eaten. And none yet have eaten the fruit of Wisdom.

Seeming to Pass Wisdom

While there is no Tsu-Do Zen wisdom to pass from student to disciple, it is acceptable to imitate the passing of wisdom.

Any method is appropriate. One can emulate the great Mahakasyapa, who smiled when the Buddha held up a flower. One can use an artificial flower, to emphasize the imitative character of the exchange.

One can also use pseudo-Tantric methods, for example, "enlightening" your friends by slapping them across the face with an old flip-flop beach sandal.

One is advised not to emulate the Zen master who killed the cat; even strangulation short of death could lead to criminal consequences.

Spiritual practicioners have long known that loonily acting like you are enlightened can really liven up a long day of "practice." Tsu-Do Zen practicioners can enjoy similar benefits by imitating this imitative behavior.

It is nearly midnight of the first day of the year, Pacific Standard Time, January 1, 2002. At the turning of the year it is traditional to sweep out the old and ready oneself for the new. Something is ready for the cosmic dustbin. Old clothes and worries, shabby doctrines worn from overuse, tired attitudes that have stacked up inside us.

We just breathe it all out.

Outside, the wind is blowing away all of the mist that has obscured the moon. The clouds are majestic, the mountains, still. A new year is just a facet of eternity.

From standing we proceed to treading. Why speak of the thousand miles? Just take that first step.

Tonight, they changed the format of the website twice. Even so, Tsu-do Zen is still not Zen.

There are answers to the questions that I store in my mind, But Tsu-Do Zen blocks them from my recollection, Along with the questions and the mind.

This great block of Tsu-Do Zen has obstructed the path of all practicioners. They cannot get past it, Yet they do.

This morning I knew it had snowed Before I looked outside

I was both pleased and slightly disappointed, as I had the thought to ride my motorcycle.

Baksheesh has been rejected by many, who shun his utterances like his company.

Nevertheless, Baksheesh is occasionally seized by notions that he fancies to be of importance, and true, and he reasons thus with himself. "If I fail to speak what I believe to be true and perhaps of value to some, because I fear criticism, then I am silencing the Dharma to protect my own vanity; further, since my existing reputation is so low, the risk of incurring further criticism is small, almost negligible. Since I do not fear misleading people by promulgating a Dharma of No-Evidence, because people cannot be misled with non-assertions, and I believe it to be the Elixir of the Heroes, I will tell whomever I please.

The Gospel of the Dharma of No-Evidence by Baksheesh the Madman

THUS DID IT OCCUR TO ME:

As to that which cannot be known, each one is free to believe as they wish.

Assertions beget contentions.

Contentions abort peace.

Peace is the ground of serenity.

Serenity is the home of faith.

This is the Gospel of the Dharma of no-evidence.

Faith that relies on nothing is invincible.

To seek evidence of our deathless nature is fruitless, we must do it until we understand this.

The Revered Buddha looked everywhere for evidence of the state beyond death, and found it nowhere.

Only when he looked in the One place he had not, did he discover the object of his quest.

When dawn arrived, he held the sword of wisdom in his hand, and all the demons of darkness had fled from the arrows of the all pervasive sun from his own Mind.

Concretize nothing of this story and do not rely on it for evidence.

It is the truth, but you need not ruminate on it.

Within your own mind, the same Buddha resides.

You will find him much more quickly there than at the temple!

Praise to the stainless sword of faith in the imperishable nature of the mind, for it vanquishes all pettiness and makes heroes of those who hasten to battle their own attachment to erroneous beliefs.

Darkness clings to us because we know not how to dispel it, and mistake it for our true condition.

Bewilderment regarding our own identity should not be considered the natural state.

"Common" would be more accurate.

Since nothing is closer to us than what we are, it seems strange that we should entertain a moment's doubt about who we are, yet we do, and much to our dread and suffering, as the Buddha made it the jumping-off point of a quest that he began by looking in all the wrong places.

So when you feel like you're not getting anywhere, you can comfort yourself -- the Buddha felt the same way, but worse, until he cracked the nut of his own closed mind, and ate the nectar of the yummy, nourishing center of self-knowledge.

Rumor has it, he also discovered that the nature of our self is unoriginated, i.e., it didn't come "from" anywhere. So, it's not likely to "go" anywhere, either. That can't be disproven, so you are free to believe it.

Now someone might say, in a cocky voice, "It doesn't help you much to know that the Buddha discovered his own nature, if you still don't know your own."

At this point we have two choices -- to say nothing, which will at least leave him guessing, or to observe that even a small amount of help in a dire situation is welcome.

And the situation certainly is dire, with death lurking everywhere and collecting victims constantly.

It is as if we were all languishing in prison, and we cherished the memory of the one man who got out.

And it must be that he got out, or there is no Dharma worth discussing.

Buddha must have overcome mortality, or he would never have gotten up from his spot under the Bo tree.

So you see, in the very story of the Buddha, by inescapable logic, there is evidence that our own nature is deathless.

You must watch out for stories like these, and not rely on them as evidence. They are like fool's gold, not to be mistaken for the genuine element, and will betray you if you give up your search for faith without evidence.

The lives of the saints are a source of evidence, although a fairly refined form of evidence, that is used to wean us off toxic mistaken beliefs.

But 1% poison and 99% sugar is still deadly at the right dose, and thus you are cited to the Buddha's example solely to induce emulation, not to win arguments.

For through accurate emulation, we do in fact discover our own nature, we do not become it.

The Buddha does not say "sit like me," or "stand like me," or "walk like me."

The Buddha says, "Be yourself, and don't make assumptions."

Can you do that?

Do you hear laughter?

The Nature of The Mind Cannot Be Deduced by Successfully Reproducing Its Activities

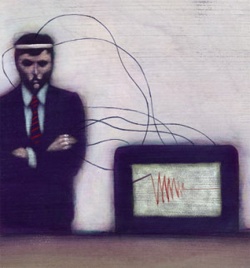

It is often said that mental activity is produced by the operation of our physical body. It generates a light electromagnetic field, that fluctuates in intensity in synchrony with subjective, psychological events. Likewise, changes in diet, environment, and mood all interact so closely as to cause us to question -- why believe in the existence of deathless mind for which there is no evidence?

First, it is an expression of our freedom. It is our right to believe as we wish regarding matters beyond proof.

Second, if you believe you can discover your own identity, you are more likely to try.

Third, if your belief is in line with your deepest desire, it may be an intuition of rightness.

Fourth, if your belief does not rely upon evidence, and looks only to the nature of the believer to support itself, you will be in an observant posture to perceive reality and obviate the need for belief.

The Nature of the Mind Cannot Be Deduced By Successfully Replicating Its Activities

It is asserted that evidence establishes that the body generates the subjective experience of self-awareness called mind, through the myriad interconnections of billions of neural cells concentrated in the cranium, and distributed to the extremities from the neural axis of the body, the spinal cord.

Since the phenomenon called "life" is a category defined by physical, self-reproducing life-forms, and because "intelligent life" is a subset of "life," it is argued that intelligence cannot and does not exist independent of living beings with sufficient neural sophistication to generate electromagnetic/chemical reactions that somehow translate into subjective experiences.

Where that border is crossed is unknown. We might hypothesize computers of great sophistication, able to bake bread, play the violin, and change a baby's diaper; however, none of this increased versatility would move the computer one iota toward sentience.

An incredibly sophisticated robot will never harbor a secret desire to be human.

One thing does not become another. Machines do not become human. Which does not mean machines can tell us nothing about ourselves. We made them. They mirror and magnify our desire, but they never become alive.

The electromagnetic fields of the body might well operate as vehicles for deathless mind, which, as it shines through into the visible world, takes on the subjective nature of feeling as a living being does -- alive -- and simultaneously fills a few square feet of protoplasm with the energy of that which desires to be.

Under this theory, degeneration, the decay of the transmitter is preventing transmission of clear awareness. Death means the channel has been cut.

small "b" buddhists

I think of them as "small b" buddhists.

Buddhists whose thoughts bother them. It occurs to me that good thoughts don't bother me.

They please me, interest me.

True, they might distract me from experiencing the exact texture of my whole-grain muffin, or from noticing exactly how my butt feels pressing on my meditation cushion, or other of these incredibly important sensations that lead some meditators to write whole books about it.

(Of course, while they're writing their books, they temporarily have to relinquish the great bliss of really feeling things, but ...) But back to good thoughts. I just don't think they're a problem.

I think "I should plant those trees," or "I should hug my wife," or "I should do that client's work," or "I should eat dinner." None of those thoughts are problems. Can't hardly do without 'em.

But a small "b" buddhist has a problem with thoughts in general.

The problem is described variously -- they are "random," or "distracting," or "passionate" or "obsessive."

This is like someone looking out their window and seeing a lot of weird people in the neighborhood, skanky people with desperate eyes and sneaky movements, and thinking "People are troublesome.

I need to move to the desert where there are no people."

No, you need to realize you're living next door to a crack den and find a better neighborhood.

Actually, it's more like you're the landlord and you need to find some new tenants, nice people who have families and kids and grandmas. That way when you look out the window, you'll see nice people.

Kids playing ball, and hopscotch. Old ladies going shopping. Old men planting flowers. People taking out the garbage, or going to work.

My point is, if you don't like the thoughts you're having, you can treat them all like roaches and call the exterminator, or you can ask yourself why your brain is crawling with vermin.

Could it be because you are sitting on a pile of garbage?

The small "b" buddhist sees things in a flat, over-generalizing way.

They look at other people, who are undisturbed by their thoughts, and they feel disgust, as if they lived in a roach-infested flat and didn't hate it.

It doesn't occur to them that those people may enjoy their thoughts, or even cultivate good thoughts and have no need for cognicide.

When you are annoyed by thoughts that are "random," what have you got there? Just a hostility toward the way mind works. "Random" is also "unpredicted" or "creative."

You will find that a serious small "b" buddhist is often not so creative, beyond trying hard to taste their muffin or feel their butt on their cushion.

When you have a thought that is "obsessive," you probably are ignoring something like visiting your mom, or paying bills, something important you need to do.

You may hate your "passionate" thoughts because you have failed in relationships, but feeling your own butt is a pale substitute, frankly, for feeling someone else's.

And as far as thoughts that are "distracting," well that's just relative -- it's quite likely that whatever you are distracted by is something you've failed to pay attention to in the past and now it's bugging you.

Obviously, people feel vexed, stressed, off center, and they want to do something about it.

But if their gospel is to get rid of thoughts altogether, or somehow get them all to lie down quietly, I think it's a flat, uninteresting path. It ignores how much fun and vitality comes from good thoughts.

It projects an image of dysfunctionality that pervades their writing about "the mind" as if it were an unruly servant needing schooling.

They become rigorously "small b" buddhists because they see their nature as a mundane project in keeping order, rather than as a fun, hopeful, creative thing, like the view of life that a happy young kid would have. I mean, remember buoyancy? Good humor?

That's enough for today.