Vimalaprabhā

Vimalaprabhā Laghukālacakratantrarājatikā

These manuscripts are significant in terms of their historical, intellectual and aesthetic value.

Tantra apart, the text contains detailed discussions of astrology and astronomy.

There is also the lesser known and rare wisdom of svarodaya. Ayurveda occupies an important thematic focus in the Tantra.

Many of Indian philosophical concepts are discussed in depth in this treatise.

Measurements of the globe are given which are more detailed than those given in the Abhidharmakosa, a celebrated 4th Century text authored by Acharya Vasubandhu, which is itself a veritable encyclopaedia of information.

The importance of this manuscript is paramount also given the unfortunate turbulent situation in medieval India, where several Buddhist manuscripts were lost

.

Vimalaprabhā Commentary.

I. The great exposition on the origination of the body, speech, and mind and on the investigation of the four noble truths

II. The great exposition of the truth of origination,

III. The great exposition on the battle between the cakravarti and barbarians, on the tantric families of Kalacakra, and on the origination of the families of the Nadis

IV. The great exposition on the characteristics of unfavorable death and on the severance of the Nadis

V. The great exposition on the principles of Kalacakra and on the characteristics of the moment

VI. The great exposition on elixirs, midwifery,

VII. The great exposition of our own and others'

Vimalaprabhā Commentary.

Vimalaprabhāṭīkā of Kalki Śrī Puṇḍarīka on Śrī Laghukālacakratantrarāja by Śrī Mañjuśrīyaśa.

I. The great exposition on the origination of the body, speech, and mind and on the investigation of the four noble truths

II. The great exposition of the truth of origination, and so on

III. The great exposition on the battle between the cakravarti and barbarians, on the tantric families of Kalacakra, and on the origination of the families of the Nadis

IV. The great exposition on the characteristics of unfavorable death and on the severance of the Nadis

V. The great exposition on the principles of Kalacakra and on the characteristics of the moment

VI. The great exposition on elixirs, midwifery, and the like

VII. The great exposition of our own and others'

Other Titles - Vimalaprabhāṭikā of Kalki Śrī Puṇḍarīka on Śrī Laghukālacakratantrarāja by Śrī Mañjuśrīyaśa

The esoteric Buddhist Kalacakra Tantra text and its eleventh-century commentary, the Stainless Light (Vimalaprabha).

Building upon the Chapter on the Cosmos and particularly the Chapter on the Individual which provide the theoretical background to the Chapter on Sadhana, and the reasons for the given structure and contents.

The Kālacakra tantra is a Buddhist tantra, which means that it reveals a method for the completion of the Mahayana path by following the principles of tantra in general and those of highest yoga tantra specifically.

It is tantra because its methodology involves the utilization of the transformative power of the mind focused upon attainable forms of enlightenment to initiate an alchemical process of transmutation.

Forms of physical and mental enlightenment are mentally imposed upon ordinary external and internal forms to such an extent that, through the power of faith, understanding, and concentration, these visualized enlightened forms are held to actually replace the ordinary phenomena that act as their bases.

This practice, when fully developed in the yogi’s mind, is combined with the physiological manipulation of the vajra body that will eventually transform the mind, and all that is created by that mind, into the “real thing”—the enlightened mind and form of a buddha.

The practice of the Buddhist tantric yogi is built on deep faith and conviction in those practices and their authenticity.

In the eyes of such a practitioner, the Kālacakra tantra was first taught by the Buddha himself in the form of the deity Kālacakra.

The initial teaching was given in south India in the sacred place of Dhānyakaṭaka from within an initiation mandala formed from the constellations, in which the sun, moon, and the two shadow planets, Rāhu and Kālāgni, were uniquely positioned in the four directions.

Prime among the audience of thousands of bodhisattvas and celestial beings was King Sucandra of Shambhala, a fabulous kingdom somewhere on this earth where the Kālacakra teachings were held and propagated until their appearance in India in the tenth or eleventh century C.E.

Sucandra, a manifestation of the bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi, returned to Shambhala and wrote down the teachings in twelve thousand verses. This was the Root Kālacakra Tantra and was known as the Supreme Original Buddha.

From then on he taught the tantra to the inhabitants of Shambhala until his death.

The lineage was taken up by his descendants and royal successors, who continued his work of spreading the Root Tantra.

About six hundred years after the death of Sucandra, the Shambhala king Mañjuśrī Yaśas compiled an abridgement of the Root Tantra for the benefit of the many non-Buddhist adherents in Shambhala.

This abridgement is known as the Condensed Kālacakra Tantra and is the work referred to when the textual term Kālacakratantra is mentioned.

Its commentary, composed by Puṇḍarīkā, the son and royal heir of Mañjuśrī Yaśas, is called the Vimalaprabhā or Stainless Light.

It is often referred to as the Great Commentary. The Root Tantra itself did not survive in its entirety.

The “stainless light” in Khedrup Norsang Gyatso’s title refers to Puṇḍarīkā’s commentary. Ornament of Stainless Light is an overview of the five chapters of the tantra and seeks to explain the major points and clarify areas of doubt rather than being an exhaustive commentary.

Khedrup Norsang Gyatso was a teacher of Gendün Gyatso, the Second Dalai Lama (1476–1542), and a disciple of Gendün Drup, the First Dalai Lama (1391–1474).

After extensive study and a four-year retreat, he became well known as a Kālacakra scholar and a proficient astrologer.

Gendün Gyatso praised him as being inseparable from the Shambhala king Mañjuśrī Yaśas.

He was also learned in Sanskrit, poetry, and composition. He composed, in collaboration with Phukpa Lhündrup Gyatso, the Puṇḍarīkā Transmission:

A Treatise on Astronomy and founded the Phuk tradition upon which Desi Sangyé Gyatso’s White Beryl was based.

Apart from astronomy he also composed works on the Guhyasamāja tantra and on dependent origination.

When the tantra found its way to India in the tenth or eleventh century, it was not always enthusiastically received.

This tantra was one of the last tantras to appear in India, and it seemed to contain concepts that were more akin to the non-Buddhist Sākhya and Jain philosophies than that of the Buddhists.

Nevertheless it eventually found acceptance and took its place among the other great tantras of India.

A succession of great masters, such as Nāropa, Kālacakrapada (who some identify with Nāropa), Avadhūtipa, Abhayākaragupta, and many others, wrote supplementary works to the tantra and succeeded in transmitting the lineage to future generations.

Not long after the tantra arrived in India, it was brought to Tibet by the eleventh-century translator Gyijo Öser, who is widely credited with making the first Tibetan translation of the Kālacakra.

It was eventually translated into Tibetan at least fourteen times, and two main traditions emerged.

The Dro tradition was founded upon the translation by Dro Lotsāwa, who worked with the Kashmiri Pandit Somanātha in Tibet, and the Ra tradition was begun by Ra Lotsāwa (1016–98), who worked with the Indian master Samanthaśrī in Nepal or Kashmir.

It seems that the Ra lineage became influential within the dominant Sakya tradition that flourished at those times and thereafter within the Geluk tradition founded by Jé Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), whereas the Dro lineage was predominant in the Jonang tradition that was made prominent by Dölpopa (Sherap Gyaltsen 1292–1361) and others.

The fourteenth century saw the Kālacakra become especially import ant to both Dölpopa and another highly influential figure, Butön Rinpoché (Rinchen Drup 1290–1364).

These two great masters were responsible for popularizing the Kālacakra and cementing its reputation in Tibet.

Butön Rinpoche annotated and wrote extensively on the Kālacakra tantra, while Dölpopa ordered a revised translation of the tantra and its commentary, the Vimalaprabhā.

It has been said that Dölpopa was the first master to conceive of the idea of giving the Kālacakra initiation as a public event.

From then on the Kālacakra lineage has not only survived but flourished in Tibet, mainly in the Geluk tradition but also in the Sakya, Kagyü, and Jonang traditions.

Although these days there is a tradition of giving the Kālacakra as a public and unrestricted initiation, this probably wasn’t always the case. There is, however, a record of the Panchen Lama giving the initiation in China in 1932 in a huge thirty-two-foot sand mandala.

The Practice and Philosophy of Tantra

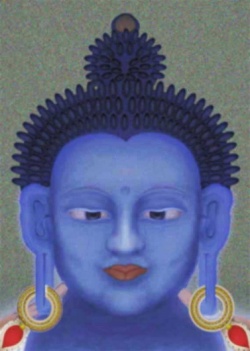

The state of mind most suitable for the transformative processes of tantra is a very subtle level of mind called the mind of clear light.

This is a subtle level of consciousness and not a newborn state of mind developed by practice. It exists therefore within the mental continuum of every sentient being but is rarely evident or manifest.

It may surface infrequently during life and will appear naturally during the process of dying.

The yogi employs completion-stage tantric methods to make manifest this mind of clear light. This involves the manipulation of the vajra body, which mainly involves bringing into the central channel the winds that normally would flow through the left and right channels of the vajra body.

The subtle mind of clear light is the best state of mind in which to focus on an understanding of emptiness, the ultimate and true nature of all phenomena. This mind of clear light is then developed into the nature of bliss.

This bliss is not a heightened form of worldly happiness, nor is it the bliss brought on by sustained meditative concentration alone, but is developed generally from penetrative focusing upon points within the cakras of the vajra body and specifically from what are called the four joys.

These four joys arise from the elemental drops, which normally are stationary within the vajra body, moving up and down the central channel.

This movement in turn is brought about by practices of union involving a real or imagined consort or from the practice of generating the inner fire.

Eventually the subtle wind that accompanies the subtle mind is developed into a form resembling the enlightened form that is the goal of practice. This is known as the illusory body.

The clear-light mind of bliss and emptiness and the illusory body are a union that develops into the dharmakāya and rūpakāya—the mind and form of an enlightened being.

In tantra a student must work closely with his or her guru—much closer than in the Perfection or Sutra vehicles.

Nowhere is this more true than at the outset of tantric practice during the process of initiation. One can only enter the tantric path through the doorway of such a transmission.

The term tantra is often etymologized as “continuum,” and while this continuum refers to the unbroken continuum of the primordial or clear-light mind, it may also refer to transmission in the form of an initiation.

During the initiation ceremony transmission is from the guru to disciple, and it is the guru, therefore, who holds the key to the door of the celestial mansion housing the deities of the tantra.

The disciple needs to request someone else to confer the initiation ceremony because the nature of the spiritual phenomena to be transmitted is such that an ordinary unenlightened person could not do it.

For example, because of its nature, the fourth or word initiation can be successfully transmitted by Buddha Vajradhara and no one else.

The vajra master conducting the ceremony is therefore understood to be Vajradhara in the form of a guru.

In the yogic pure view, oneself and one’s immediate environment are viewed through celestial eyes, thus it would be inconsistent if the guru who is responsible for setting the practitioner on the tantric path were not also regarded with the same pure perception.

Therefore all the guru’s actions and behavior are understood as being solely for the guidance of the practitioner, regardless of how they might appear.

Because of this it is said that there is no act of devotion too great to be performed for the vajra master.

With initiation the practitioner enters the generation stage, which involves preparing or ripening the mind for the completion stage that follows.

The generation stage is essentially a process of pure-view development powered by meditative concentration, which overrides all habitual and ordinary pretantric perception.

Its center of focus is the celestial mansion and the deities and mandalas housed within it.

These are regarded as purifiers or transformers of ordinary existence, which takes the form of our perceived world. In this way the generation stage prepares the mind for the radical procedures of the completion stage.

The completion-stage practices make use of the vajra body.

The purified and powerfully concentrated mind developed by the generation stage focuses on and penetrates the vajra body at the locations of elemental drops and cakras, thereby causing the winds to travel there.

The primary purpose of this practice is to bring the winds into the blocked central channel and so make manifest the subtle mind of clear light.

This clear-light mind is focused upon emptiness, while the accompanying subtle wind eventually arises in the form of the illusory body.

Distinctive Features of the Kālacakra Tantra

The Kālacakra follows this general methodology of tantra, although it is unique in some aspects.

The Condensed Tantra or Kālacakratantra has around 1,030 verses arranged in five chapters. These chapters are Realms or External World, Inner, Initiations,

Methods of Accomplishment, and Gnosis.

The first chapter discusses the external world—its creation, features, and dimensions.

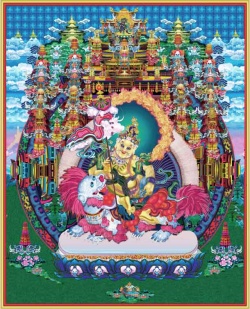

According to the Kālacakra tantra, the external world is centered on Mount Meru surrounded by various lands or continents, with the four elemental mandalas below as a foundation and the planetary and stellar systems above.

The purpose of this first chapter is an esoteric one in which this external world is regarded as a product of the karma of sentient beings, and its features, therefore, are regarded as suitable phenomena for purification by the practices of the generation and completion stages.

The dimensions of this Kālacakra universe correspond perfectly to the enlightened phenomena of deity and celestial mandalas that become the purifier or transformer of the world.

This is a karmicly created correspondence that is exclusive to those destined to be Kālacakra practitioners.

The human body in its dimensions also corresponds to this external environment.

The size, shape, color, and general description of a world realm as found in Kālacakra differs greatly from that described in Abhidharma-based literature.

Scholars might say that the reason for these discrepancies is that the Kālacakra literature was probably composed in the latter half of the first millennium somewhere in central Asia and had therefore lost touch with fundamental tenets of Buddhist cosmology.

This could also explain the amount of non-Buddhist Sāṃkhya terminology employed throughout the text.

Some Indian scholars of the past attempted a compromise in which some parts of the tantra were deemed to be provisional and other parts definitive.

Nevertheless, the dimensions of the Kālacakra world realm correspond perfectly to the dimensions of the human body and the mandalas of the celestial mansion, and such a correspondence is essential for the Kālacakra practitioner.

The Kālacakra is also at great pains to point out that neither the Abhidharma nor the Kālacakra presentation of cosmology constitutes the sole truth on the matter to the exclusion of all other presentations, and that it is not necessary to establish such a truth because each presentation suits its own purpose.

For this reason, those who try to marry or harmonize Buddhist ideas of the cosmos with present-day scientific knowledge could well be pursuing a fruitless task.

The differences need not be resolved.

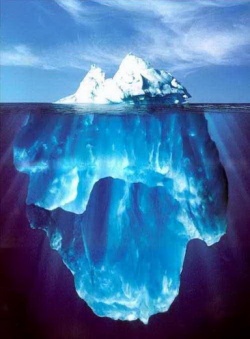

The generation-stage practices of corresponding enlightened phenomena to ordinary phenomena with a view to transformation indicates a system in which mind developed to its full potential takes precedence over objectively viewed “real” phenomena.

This important pillar of Vajrayana thought may explain its emphasis on phenomena being mind-created, particularly its assertion that all things in samsara and nirvana are generally created by the mind, or by the everpresent subtle mind and subtle wind.

The purpose of the second or Inner chapter is to present the “person composed of the six elements,” the elements being earth, water, fire, air, gnosis, and space.

This person’s ordinary body and vajra body are presented as objects for purification by the corresponding enlightened phenomena of the generation-stage mandalas.

One of the assertions of the Kālacakra is that there are no phenomena beyond the six elements.

This is applicable to bodily phenomena and is also true of the resultant enlightened phenomena, such as the five buddha families.

Therefore, an ordinary or “obscured” phenomenon included within the continuum of an ordinary being is transformed into its corresponding enlightened state by the completion stage without ever going beyond its essential elemental identity.

It is not only the major constituents of the body that have corresponding enlightened phenomena in the celestial mansion.

The process that is the very creation and development of a human form is also linked to meditative processes occurring in the generation stage. Conception, pregnancy, and birth are therefore described in detail in the Inner chapter.

Unique to Kālacakra is its assertion that enlightenment is not attained on the basis of an illusory body developed in the intermediate state, or bardo.

According to Khedrup Norsang Gyatso this is because in Kālacakra the primary and substantial basis of an enlightened body is the body of empty form, and this is not achievable in the ordinary state, whereas in other tantras the subtle wind is manifest during death clear light and used as a basis for the creation of an illusory body.

Others say that the Kālacakra completion stage needs a coarse material body for its accomplishment and that such a body is not found in the intermediate state.

The bulk of the Inner chapter discusses the channels, winds, and drops of the vajra body.

Although the vajra body exists in a subtle state, it is nevertheless what is called an obscured phenomenon and is therefore suitable for transformation. Presentations in some parts of the Inner chapter are at odds with those of other tantras.

For example, the Guhyasamāja asserts that the crown cakra has thirty-two channel petals and the throat cakra sixteen, while the Kālacakra presents the crown cakra with four petals, the forehead with sixteen, and the throat with thirty-two.

However such contradictions are resolved using the same reasoning found in the Realms chapter to explain the discrepancies in the dimensions of a world realm of the Kālacakra and of the Abhidharma.

Khedrup Norsang Gyatso] points out that Jé Tsongkhapa stated that every tantra stands on its own and that its assertions and presentations are definitive and verified as such by those yogis with meditative experience.

Other differences include the colors, functions, and pathways of the channels below the navel; the locations, colors, and flow of the winds; the Kālacakra assertion that wind flows through the central channel during the ordinary state; and the functions of the four drops.

The third chapter, called Initiations, deals primarily with the seven or eleven initiations conferred on the Kālacakra initiate. It begins with an assessment of the qualities of suitable tantric gurus—vajra masters—and their disciples, followed by stipulations for the type of mandala to be constructed for the ceremony.

The seven childhood initiations are analogous to stages of childhood and by themselves empower the disciple to practice the generation stage and to work for the attainment of worldly powers (siddhi).

There is much disagreement among Tibetan masters on the functions of the four higher and four higher-than-high initiations.

All agree that they empower the disciple to enter the practices of the completion stage and to work for the supreme siddhi of enlightenment.

Khedrup Norsang Gyatso argues that the higher-than-high, or nonworldly, fourth initiation must be conferred after the worldly, or higher wisdom-knowledge, third initiation in order to empower the disciple to complete the six-branch yoga that makes up the completion stage, and that the remaining three higher-than-high initiations are conferred subsequently.

The generation stage

The fourth chapter, called Methods of Accomplishment (Skt. sādhana), covers the generation-stage practices of Kālacakra.

As with tantras generally, the purpose of the transformative practices of the generation stage in Kālacakra is to ripen or prepare the mind for the advanced practices of the completion stage.

This involves the practice of changing ordinary perception into pure view and developing the pride of being the meditational deity, often referred to as divine pride. It is not mere visualization of the mandala and the deities.

Pure view and divine pride require complete mastery over the mind for their full implementation, and so the meditative state known as peaceful abiding (śamatha) is necessary.

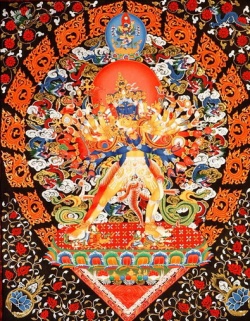

The Kālacakra celestial mansion, consisting of body, speech, and mind mandalas and over seven hundred celestial figures, and the corresponding phenomena of the inner and outer worlds are described in this chapter.

In the development of pure view, one’s environment is seen as the celestial mansion, one’s body as enlightened form, one’s possessions and enjoyments as pure bliss, one’s circle as buddhas and bodhisattvas, and one’s activities as enlightened deeds. These are known as the five perfections, and they appear to the mental consciousness and not to the senses.

These five perfections are found in actuality in the enlightened state that is the result of Vajrayana practice. Hence, the generation stage is a practice of the result as a cause.

Gyaltsap Darma Rinchen explains divine pride in the following way.

Representations of the self or person that is the subject of the thought “I” can be found in one’s mindstream from beginningless time up to one’s attainment of the state of Buddha Vajradhara.

This future-self Vajradhara, the goal of one’s practice, is taken as the subject of divine pride and posited as existing now. Divine pride does not mean thinking “I am a buddha, and that buddha is me as an ordinary being.”

Such a perception is distorted in the same way that the perception of a piece of rope as a snake is distorted. With this distortion ordinary or habitual perception cannot be transformed.

Therefore the “I” of the divine pride that thinks “I am the deity” is the “I” of our future enlightened form.

Kālacakra generation-stage practice begins from the creation of the protection wheel to guard against interference and moves on to practices corresponding to the ordinary processes of dying and being reborn.

A meditation on emptiness called the four gateways to freedom corresponds to actual death.

Following this is a practice known as the emanation of the sovereign mandala, which corresponds to the formation of the body in the womb.

This involves creating the external elemental mandalas, on top of which is placed the celestial mansion.

This corresponds to the formation of the external world and to the mother’s womb.

This is followed by the formation of the Kālacakra deities within the mansion, corresponding to the month-by-month development in the womb.

Of the four branches of the generation stage, this initial practice is known as the branch of approximation and corresponds to a resultant state of enlightenment known as body vajra.

The second branch of the generation stage corresponds to ordinary birth and is known as the branch of near accomplishment or as the meditation on the sovereign activities, corresponding to the resultant state of enlightenment known as speech vajra.

This involves a meditation called arousing by song, in which Kālacakra and consort are aroused from their blissful state by the songs of four goddesses.

This process corresponds to the movement of the four winds within the mother’s womb that encourage the child to move into the outside world.

After the deity and consort have awoken into the world, the mandalas are emanated again.

Deities known as wisdom beings are summoned and merge with mandala and assembly to become the samaya mandala.

These activities correspond to the child’s first engagement with the outside world through the medium of the senses, which is brought on by the movement of the winds.

The second branch of the generation stage concludes with the meditations known as sealing, in which the principal deities of the mandala are sealed or marked with various syllables to indicate their family or clan.

This is followed by meditations involving blessings of body, speech, and mind and a purity meditation in which each enlightened feature of the mandala is identified with an ordinary phenomenon.

The third branch of the generation stage is that of accomplishment or drop yoga and corresponds to the resultant mind vajra and to the ordinary process of the development of seminal fluid up to the age of sixteen.

The fourth branch is that of great accomplishment or subtle yoga and corresponds to the resultant gnosis vajra and to the halt in the growth of seminal fluid at the age of sixteen.

These two practices involve the simulation of the completion-stage practice of moving the elemental drops of the vajra body through the central channel to induce the four joys.

These require the use of an imagined or actual consort and are ripening processes for similar practices performed during the completion stage.

The completion stage

The Kālacakra generation stage is also known as contrived yoga and conceptually created yoga. Its practices involve the development of mentally contrived creations together with the recitation of mantras.

This is the meaning of conceptual in this context.

The completion stage is nonconceptual in the sense that such mental construction is no longer necessary.

Empty-form deities and signs arise naturally within the clear-light mind of their own volition, like the images seen in a clairvoyant’s mirror.

The completion stage of highest yoga tantra is usually defined by its accomplishment of having induced the winds that normally flow through the two side channels to enter the central channel.

According to Khedrup Norsang Gyatso all six yogas of the six-branched yoga that make up the completion stage fulfill that definition.

However some commentators say that the practices of the first two yogas, withdrawal and meditative absorption, merely prepare the winds of the left and right channels for entry into the central channel by making them more pliable, and that they do not properly enter the central channel until the third yoga.

The Kālacakra completion stage is taught in the Condensed Tantra in the fifth chapter, called Gnosis (Skt. jñāna).

The six-branched yoga already mentioned is not the same as the six yogas of Naropa nor is it identical to the similarly named six-branched yoga taught in the Later Guhyasamāja.

Like the generation stage before it, the practices of the completion stage are divided among the four branches of approximation, near accomplishment, accomplishment, and great accomplishment.

The first four yogas are grouped in pairs, so that withdrawal and meditative absorption comprise approximation, and the third and fourth yogas, praṇāyāmā and retention, make up near accomplishment.

The fifth yoga, recollection, is accomplishment, and the last yoga, meditative concentration, is great accomplishment.

These four categories also correspond to the four vajras mentioned above, the body, speech, mind, and gnosis vajras.

There are no intervening stages or practices between the complete accomplishment of the six yogas of the completion stage and the enlightenment that is the state of Vajradhara.

In the first yoga, withdrawal, the winds of the left and right channels are initially induced into the central channel. This purifies the central channel and prepares it for the subsequent yogas.

Withdrawal is practiced by following a strict and ascetic meditational procedure in a blacked-out room without a trace of light for the night yoga and under the open skies for the day yoga.

The discipline of this yoga includes a strict and carefully positioned bodily posture, a particular gaze of the eyes, and a mental placement focused on the central channel’s upper opening, which is situated between the eyebrows.

These practices bring the winds into the central channel for the first time, and the clear-light mind is made manifest.

This activation of the clear-light mind is indicated by the empty-form appearance of ten signs, including such things as smoke and a mirage, which themselves are reflections or images of the clear-light mind.

These empty-form appearances are held and stabilized by the second yoga, meditative absorption.

The term withdrawal refers to the withdrawal of the five senses from their external objects to be replaced by celestial senses developed by the mental consciousness.

This differs from the withdrawal yoga of the Guhyasamāja tradition, where the senses withdraw into their objects to be enjoyed as expressions of bliss and emptiness.

In the first two yogas, the clear-light mind is made manifest and merges indivisibly with the empty forms, particularly the empty-form appearance of Kālacakra and his consort.

These two yogas are known as body vajra meditations and bear some resemblance to the completion-stage practice of the Guhyasamāja tradition known as body isolation, in which phenomena are isolated from ordinary perception and appear as expressions of bliss and emptiness.

In the first two yogas of Kālacakra completion stage, phenomena are severed from the senses and are perceived by celestial and clairvoyant senses.

The function of the third yoga, praṇāyāmā, is to bring the winds fully into the central channel and to block off the left and right channels. The implementation of praṇāyāmā consists essentially of two practices known as vajra recitation and vase yoga.

Vajra recitation involves a process where the innate tones of the incoming and outgoing breaths traveling through the central channel are identified with mantra syllables.

In the practice of vase yoga, the upper and lower winds of the vajra body are brought to a point at the navel where they unite as a vase-shaped sphere.

Due to this concentration of mind and winds at the navel, the empty form figure of Kālacakra appears effortlessly at the navel.

The yogi focuses on this empty-form deity with a clear-light mind and merges with it to generate the divine pride of being Kālacakra.

The vase-yoga concentration of the winds at the navel is the inner cause for the blazing of the inner fire, which melts the elemental drops, also known as bodhicitta, which fall and rise again through the central channel to create the four joys.

The bliss of the four joys is used to meditate on the emptiness that is the ultimate truth of phenomena, known in Kālacakra as nonaspected emptiness.

The fourth yoga, retention, retains the winds in the central channel and brings them into the drops that reside at the cakras along the central channel.

Praṇāyāmā and retention are speech vajra meditations, and in the Guhyasamāja tradition vase yoga and vajra recitation are identified as speech isolation practices.

The fifth yoga of the six-branched yoga, recollection, is so called because the empty-form Kālacakra with consort Viśvamātā that arose during the appearance of the signs in withdrawal yoga is now recalled and develops into an actual phenomenon rather than a mere appearance.

The yogi ignites the inner fire and generates the bliss of the four joys by way of vase yoga or by relying on two types of consort.

The clear-light mind develops into that bliss, and the yogi focuses on and merges with this empty-form Kālacakra as an actual phenomenon. This is known as the recollection body, and the empty-form consort Viśvamātā is the mahāmudrā consort.

Desire for this mahāmudrā consort leads to the final yoga and the creation of the highest form of bliss in Kālacakra, unchanging bliss.

The sixth yoga is meditative concentration. Khedrup Norsang Gyatso describes meditative concentration as:

A gnosis that is the indivisibility of an unchanging great-bliss consciousness and the object of that consciousness, an empty form endowed with supreme characteristics that has the power to transform all aggregates, sources, and elements into nonobscured phenomena, as quicksilver transforms base metal into gold.

This describes a union with the mahāmudrā consort that brings about a stacked arrangement of 21,600 bodhicitta drops in the central channel.

These create a similar number of instances of unchanging bliss, which in turn consume proportionate parts of the material body and gradually transform it into the empty-form body of Kālacakra.

At the same time, each of the 21,600 instances of bliss destroys its share of the perception that holds to the true existence of phenomena.

The result is the enlightened union of an unchanging bliss consciousness one-pointedly focused upon ultimate truth, emptiness, and united inseparably with an empty-form, rainbowlike, and obscuration-free Kālacakra and consort known as Kālacakra in mother-and-father embrace.

No other tantra employs this methodology for its final transformation into enlightenment.

A major difference between the Kālacakra and other tantras involves the creation of two bases or foundations that through meditational development will transform into the enlightened mind and enlightened form.

All Buddhist paths of sutra and tantra are paths of cause and effect in the sense that attainments along these paths are reached by creating their proper causes within the mindstream of the practitioner.

Although tantra utilizes the result as the path, it is still subject to the law of cause and effect.

Therefore the completion stage must generate causal phenomena that will develop into enlightened results.

For the enlightened mind or dharmakāya, this completion-stage causal phenomenon is the subtle clear-light mind developed into the nature of bliss and focused single-pointedly upon emptiness.

This subtle state of mind exists unmanifest in all sentient beings, and therefore all beings possess the innate cause of the dharmakāya.

The Kālacakra, in agreement with other tantras, accepts this subtle mind as the cause of the dharmakāya.

However it differs from other tantras on the causes that develop into the rūpakāya, or enlightened form in the aspect of the deity of the tantra.

It is the yogi’s identification with an empty-form Kālacakra that is the basis and cause for his future enlightened form in the aspect of Kālacakra.

Other highest yoga tantras present an illusory body developed from the subtle or primordial wind that acts as a mount for the primordial clear-light mind as the basis for the future enlightened form of the yogi.

In Kālacakra, therefore, empty form as a product or reflection of the subtle clear-light mind is the basis for the development of both dharmakāya and rūpakāya.

In Kālacakra literature the subtle or primordial wind is not mentioned at all.

The Jonang Tradition

The practice and philosophical interpretation of Kālacakra will normally follow the philosophical tenets of the tradition or lineage into which it has been transmitted.

The Geluk tradition founded by Jé Tsongkhapa, for example, will interpret Kālacakra philosophy, especially as regards emptiness or ultimate truth, in the light of the Middle Way philosophy of the great Indian masters Nāgārjuna and Candrakırti.

However, in the case of the Jonang tradition, the Kālacakra literature itself informed this particular tradition’s tenets.18

Under the leadership of Dölpopa Sherap Gyaltsen, Jonang Monastery in the Jonang region of Tsang in central Tibet became the center of a new and radical philosophy conceived from the Kālacakra literature.

Many sutras, tantras, and Indian treatises talk of a phenomenon existing innately in all beings that is pure of all defilement, untouched by desire, anger, and ignorance, and that is the very essence of our being. Sutra descriptions of this phenomenon are found, for example, in the Laṅkāvatārasūtra, which belongs to the Buddha’s third turning of the wheel of the teachings.

In Indian commentaries such as the Uttaratantra by Maitreya, it is referred to the as buddha nature or buddha essence (tathāgatāgarbha) and is likened to a gold statue covered in filthy rags, and to gold lying hidden in a poor man’s garden. Highest yoga tantras such as the Hevajra tantra talk of the innate and the primordial existing within.

The Kālacakra literature talks of empty-form images, which arise of their own volition, uncreated by mind, like images arising in a clairvoyant’s mirror.

The highest of these images is the empty-form Kālacakra and consort that arise in the completion stage.

Dölpopa asserted that this Kālacakra mahāmudrā empty form is the tantric form of the buddha essence taught in the third turning of the wheel of the teachings and that the path of revealing and developing it is the path to enlightenment as taught in the Kālacakra.

This buddha essence was held to be ultimate reality, and became known as shentong, “emptiness of other” or “extrinsic emptiness.”

This was in direct opposition to the ultimate truth referred to as rangtong, “emptiness of self” or “intrinsic emptiness,” that was propagated by the Geluk and Sakya traditions.

According to the Jonang tradition, ultimate-truth emptiness is shentong because it is empty of all other conventional and false phenomena.

It is not rangtong because it truly exists and is not empty of itself. All phenomena other than shentong must be rangtong because they are false and only imputed by mind.

Even the emptiness taught in the perfection of wisdom sutras of the second turning, which was propagated by Indian masters such as Nāgārjuna as being the definitive Middle Way philosophy, is not the ultimate emptiness because it is devoid of characteristics or features and is therefore without essence, whereas shentong itself is known as the Great Middle Way.

Therefore, in sutra the third turning of the wheel was the definitive turning, and the second provisional and in need of interpretation. In tantra, shentong is apotheosized as the meditational deities, in particular Kālacakra and his consort.

Much of the rangtong-shentong debate centers on the meaning of the Kālacakra term empty form or emptiness form, which is linguistically close to the term emptiness, and used as a synonym of ultimate truth.

Khedrup Norsang Gyatso, and the Geluk rangtong tantra tradition in general, say that in Kālacakra literature the term emptiness sometimes refers to conventional-truth empty form and not always to ultimate-truth emptiness.

United with emptiness or embracing emptiness may at times refer to the conventional phenomenon of union with the empty-form mahāmudrā consort rather than ultimate-truth emptiness.

Therefore, they discern two kinds of emptiness in the Kālacakra: ultimate-truth emptiness, or nonaspected emptiness, and empty-form emptiness, or aspected emptiness.

Some commentators say therefore that the emptiness in the term bliss and emptiness, when found in Kālacakra literature, refers to the empty-form mahāmudrā consort.

This is because union in Kālacakra, both on the path and in the enlightened state, refers to the clear-light mind in the nature of bliss merged with empty form.

However, this does not mean the ultimate-truth emptiness as taught in the sutras by the second turning and by Nāgārjuna has no place in Kālacakra, because the focus of the bliss in bliss and emptiness is on ultimate truth or nonaspected emptiness.

Therefore Khedrup Norsang Gyatso explains aspected emptiness as a conventional-truth empty form, such as the mahāmudrā consort endowed with every feature of enlightenment, and nonaspected emptiness as being the ultimate truth arrived at through analytical investigation of the aggregates.

Opponents of the shentong view also say that shentong philosophy is redolent of early Indian Vedanta and Sāṃkhya non-Buddhist philosophies, with their concepts of an all-pervading, indivisible, and causeless phenomenon that represents a final and truly existent reality and that exists as a findable phenomenon separate from conventional appearance.

This is the same charge that had been leveled at the Kālacakra tantra itself by its Indian and Tibetan opponents.

Kālacakra’s rather radical approach to the path of mantra, its leanings toward Sākhya terminology, its presentation of empty form, the attainment of enlightenment by way of the 21,600 instances of bliss, the omission of any reference to an illusory body formed from the subtle winds, and differences with the Abhidharma on dimensions of the universe, all contribute to make the Kālacakra a unique tantra.

Masters such as Chomden Rikral (thirteenth century) and even the great Rendawa (1349–1412), teacher of Jé Tsongkhapa, claimed that the Kālacakra was not a pure tantra.

Rendawa wrote a series of letters setting out his criticisms, which in turn provoked replies from adherents of the tantra. Many of these points of criticism are dealt with in Khedrup Norsang Gyatso’s work.

The Astronomy of the Kālacakra

Astronomy as employed exoterically in the Kālacakra is the science of calculating planetary and stellar movement in order to provide a measurement of time through the medium of calendars.

It is not to be confused with astrology as the term is used these days.

Predictive systems that relied upon the movements of the planets or an examination of the elements do exist in Tibetan astrology, but these were not the prime concern of the Kālacakra.

A famous maxim of the Kālacakra runs, “as without so within.” This means that the outside world is mirrored within the inner world of sentient beings. It also means that the practices of the two stages make dynamic use of this outer world mirrored within.

The esoteric purpose, therefore, of the Kālacakra practitioner becoming well versed in astronomy is to be able to correspond external planetary and stellar movement with internal processes in his own vajra body as part of completion-stage practices.

Tibetan masters of Kālacakra posit two systems of astronomy— siddhānta and karaṇa.

The former is said to be the true system of the Kālacakra Root Tantra and the latter a system in accord with general non-Buddhist astronomy that was adopted by King Mañjuśrī Yaśas when converting the Brahmin sages (ṛṣi) and compiling the Condensed Tantra.

According to tradition the “barbarians” who arrived eight hundred years after the compilation of the Condensed Tantra hid the true or siddhānta astronomy and replaced it with a flawed karaṇa system.

It wasn’t until the eleventh Kalkī king of Shambhala, Aja, reformed the karaṇa system in 806 C.E. that it became acceptable.

When the Kālacakra tantra arrived in Tibet, its astronomy, like the rest of its cosmology, was not immediately popular because of the suspicion that Kālacakra was not a true Buddhist tantra.

Astronomy and astrology had been present in Tibet for many years, some of it indigenous, some of it from China.

Moreover, astronomy had been taught in other sutras and tantras such as the Vajra Ḍāka Tantra and the Sutra of the Twelve Eyes.

However, when Butön Rinpoché and Dölpopa popularized Kālacakra, they popularized its system of astronomy as well.

The Third Karmarpa, Rangjung Dorjé (1284–1339), gave the Kālacakra initiation to the king of Hor and composed the Compendium of Astronomy in 1312.

This became the first Tibetan astronomy manual. Butön Rinpoché composed his Treatise on Astronomy: A Delight for Scholars, and Khedrup Jé wrote his voluminous Illuminating Reality.

Since those times Kālacakra astronomy has formed the basis for all subsequent development in the calculations of the sixty-year cycle, lunar months, years, equinoxes, eclipses, and so on of the Tibetan calendar.

Even though Tibetan systems of astronomy were independent enough to have individual identities, their root reference was always the Kālacakratantra.

Two main traditions of astronomy flourished for many years in Tibet.

Tsurphu Jamyang Chenpo Döndrup was a follower of Rangjung Dorjé and established a scriptural tradition of astronomy that was commentated on by Trinlepa Choklé Namgyal and Tsuklak Trengwa (1504–65).

This became the Tsur tradition.

Khedrup Norsang Gyatso and Phukpa Lhündrup Gyatso compiled the Puṇḍarīkā Transmission: A Treatise on Astronomy, which was taken up by Samgyal and others to become the Phuk tradition.

In 1681 Minling Lochen Dharma Śrī (1651–1718) composed his Light of the Sun:

A Treatise on Astronomy, and Desi Sangyé Gyatso (1653–1704) composed his White Beryl in 1687.

These two works consolidated the Phuk tradition as the major system in Tibet.

In the eighteenth century ppSumpa Yeshé Paljor[[ (1709–88) founded the New Geden tradition, which superceded the Phuk tradition.