Why monks wear robes

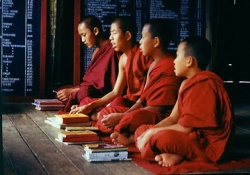

by Piya Tan, The Minding Centre, Feb 23 Feb 2011

Singapore -- Why do monastics wear robes? The first and most obvious answer is clearly so that they are not indecently exposed. This may sound banal, but in the Sabbāsava Sutta (M 2), the Buddha gives this reflection as one of a monastic's methods for overcoming defilements for sake of liberation.

A monastic is to reflect on his robes thus:

“Wisely reflecting, he uses the robe: | only for the ward off heat, | for the sake of warding off cold, | for the sake of warding off the touch of mosquitoes, flies, the wind, the sun, and creeping creatures; | for the purpose of covering up the privies, out of moral shame.” (M 2)2

The basic Buddhist monastic clothing is called cāvara. As it is a large but simple piece of saffron or ochre dyed cloth with paddy-field patterns, it is often translated as “robe.” It is also called kāsāya or kāsāva, meaning “yellowish-red, yellowish-orange,” due to its being usually dyed in water boiled with some astringent bark. The point of these definitions is to show that the early Buddhist monastic robe is one of a kind, and should not be confused with lay clothing.

In the Buddha's times, the monastic robes were simple pieces of cloth, often bits of rags and pieces of discarded shroud (that is, cloth that have no owner) stitched together. In fact, such a garb was no different from that of other monastics or from those of the followers of other sects.

In other words, the monastics had shaven heads and dressed more or less alike, and the Buddha was almost indistinguishable from other monks.

One thing is certain, however, the robes of such renunciants (that's what they really are) are clearly different from the richer dress of the laity. The message is clear: monastics are a life apart from the laity. The monastic robe is part of a simple spiritual lifestyle that one has freely vowed to live by, and as such should not fall back on one's word. More importantly, the simple robes are to remind renunciants (and non-renunciants) that their relevance is in being apart from the world, so that they can truly be able to help and heal it without getting caught up in it.

As Buddhism spread and became main stream in some cultures, the robes changed into rich and elaborate uniforms, reflective more of power and prestige than of humility and renunciation.

Understandably, in the case of one of Singapore's richest priests who was jailed for gross mismanagement of public funds in 2010, did not switch his monastic gear for proper civvies. This is symptomatic of a larger problem of a heavily money theistic “monasticism” and devotee-exploitation, which are also found in western Buddhism, but which it has been able to solve more readily than the ethnic Buddhists have done.

Oriental Buddhists surely would benefit from learning such problem-solving skills from our western siblings. If we are morally weak, Māra the evil one treats us like switches: we might be on or off without even realizing it. If the Singapore priest refused to remove his robe, a Siyam Nikaya chief high priest in Malaysia had no qualms about taking off his monastic gear to don an elegant lounge suit, topped with a bald pate, to receive his “Datuk” title from the palace. Perhaps, the ironic, no less ominous, message is that worldly power is incompatible with monastic renunciation.

In February 2011, Ajahn Brahmali, a respected forest bhikkhu in the line of Ajahn Chah, recalled:

“...a few years ago, while visiting one of my old university friends, I found myself being a bit apologetic about my strange appearance. What he responded really opened my eyes. He said the robe of a Buddhist monastic is a fairytale in "branding"; a marketing manager's dream. He said that the positive image most people have of Buddhism coupled with the very distinct appearance of Buddhist monastics is a combination that any business would be willing to pay huge amounts for. In a sense, it is a very distinct and valuable brand. After that incident I have looked upon my monastic robes quite differently. I now believe that the beautiful message of Buddha's teachings in fact is enhanced by our unusual appearance. Our robes can probably help get the message out that there is something worthwhile in these teachings.”

Ajahn Chah was clearly aware of the monastic robe's vitality and ingenuity, as attested by scholar Sandra Bell in her article on “Being Creative With Tradition: Rooting Theravāda Buddhism in Britain” (2000), on how Ajahn Chah successfully planted forest Dharma in the west. She warmly records:

“By all accounts that have been offered to me, the laity was impressed by the fact that the monks were prepared to venture forth every day in all types of weather wearing only thin cotton robes to walk single file carrying their alms bowls, receiving nothing but jibes or indifferent incomprehension from the majority of members of the public. The monks'; tenacity was viewed as a sign of devotion and obedience to their revered teacher…”

The laity has always, and should continue, to be the “quality control” factor regarding monastic conduct, as repeatedly attested in the Vinaya. Such a voice, in the spirit of the divine abodes, only serves to inspire monastics with ever greater sense of meaning and purpose of renunciation and spirituality.

Otherwise, we deserve the kind of Buddhism we get, as we euphorically add more fuel into the fire of the burning house. Let us work hard to douse the flames