Wind Horse

The wind horse is an allegory for the human soul in the shamanistic tradition of East Asia and Central Asia. In Tibetan Buddhism, it was included as the pivotal element in the center of the four animals symbolizing the cardinal directions and a symbol of the idea of well-being or good fortune. It has also given the name to a type of prayer flag that has the five animals printed on it.

Depending on the language, the symbol has slightly different names.

རླུང་རྟ་, rlung rta, pronounced lungta, Tibetan for wind horse

хийморь, Khiimori, Mongolian literally for "gas horse," semantically "wind horse," colloquial meaning soul.

Rüzgar Tayi, old Turkic for foal of the wind.

In Tibetan Usage

In Tibet, a distinction was made between Buddhism (Lha-cho, wylie: lha chos, literally "religion of the gods") and folk religion (Mi-cho, wylie: mi chos, literally "religion of humans"). Windhorse was predominantly a feature of the folk culture, a "mundane notion of the layman rather than a Buddhist religious ideal," as Tibetan scholar Samten G. Karmay explains.

However, while "the original concept of rlung ta bears no relation to Buddhism," over the centuries it became more common for Buddhist elements to be incorporated. In particular, in the nineteenth century lamas of the Rime movement, particularly the great scholar Ju Mipham, began to "create a systematic interweaving of native shamanism, oral epic, and Buddhist tantra, alchemical Taoism, Dzogchen, and the strange, vast Kalachakra tantra," and windhorse was increasingly given Buddhist undertones and used in Buddhist contexts.

Windhorse has several meanings in the Tibetan context. As Karmay notes, "the word windhorse is still and often mistakenly taken to mean only the actual flag planted on the roof of a house or on a high place near a village. In fact, it is a symbol of the idea of well-being or good fortune. This idea is clear in such expressions as rlung rta dar ba, the 'increase of the windhorse,' when things go well with someone; rlung rta rgud pa, the 'decline of windhorse,' when the opposite happens. The colloquial equivalent for this is lam ’gro, which also means luck."

Origination

In his 1998 study The Arrow and the Spindle, Karmay traces several antecedents for the windhorse tradition in Tibet. First, he notes that there has long been confusion over the spelling because the sound produced by the word can be spelt either klung rta (river horse) or rlung rta (wind horse). In the early twentieth century the great scholar Ju Mipham felt compelled to clarify that in his view rlung rta was preferable to klung rta, indicating that some degree of ambiguity must have persisted at least up to his time.

Karmay suggests that "river horse" (klung rta) was actually the original concept, as found in the Tibetan nag rtsis system of astrology imported from China. The nag rtsis system has four basic elements: srog (vital force), lu (wylie: lus, body), wangtang (wylie: dbang thang, "field of power"), and lungta (wylie: klung rta, river horse). Karmey suggests that klung rta in turn derives from the Chinese idea of the lung ma, "dragon horse," because in Chinese mythology dragons often arise out of rivers (although druk is the Tibetan for dragon, in some cases they would render the Chinese lung phonetically).

Thus, in his proposed etymology the Chinese lung ma became klung rta which in turn became rlung rta. Samtay further reasons that the drift in understanding from "river horse" to "wind horse" would have been reinforced by associations in Tibet of the "ideal horse" (rta chogs) with swiftness and wind.

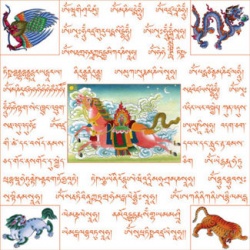

Symbolism and Usage: Tiger, Snow Lion, Dragon and the Lhasang ritual

On prayer flags and paper prints, windhorses usually appear in the company of the four animals of the cardinal directions, which are "an integral part of the rlung ta composition": garuda or kyung, and dragon in the upper corners, and tiger and snow lion in the lower corners.[5] In this context, the wind horse is typically shown without wings, but carries the Three Jewels, or the wish fulfilling jewel. Its appearance is supposed to bring peace, wealth, and harmony. The ritual invocation of the wind horse usually happens in the morning and during the growing moon. The flags themselves are commonly known as windhorse. They flutter in the wind, and carry the prayers to heaven like the horse flying in the wind.

The garuda and the dragon have their origin in Indian and Chinese mythology, respectively. However, regarding the origin of the animals as a tetrad, "neither written nor oral explanations exist anywhere" with the exception of a thirteenth-century manuscript called "The Appearance of the Little Black-Headed Man" (dBu nag mi'u dra chag), and in that case a yak is substituted for the snow lion, which had not yet emerged as the national symbol of Tibet. In the text, a nyen (wylie: gNyan, mountain spirit) kills his son-in-law, Khri-to, who is the primeval human man, in a misguided attempt to avenge his daughter.

The nyen then is made to see his mistake by a mediator and compensates Khri-to's six sons with the gift of the tiger, yak, garuda, dragon, goat, and dog. The first four brothers then launch an exhibition to kill robbers who were also involved with their mother's death, and each of their four animals then becomes a personal drala (wylie: dgra bla, "protective warrior spirit") to one of the four brothers. The brothers who received the goat and dog choose not to participate, and their animals therefore do not become drala. Each of the brothers represents one of the six primitive Tibetan clans (bod mi'u gdung drug), with which their respective animals also become associated.

The four animals (with the snow lion replacing the yak) also recur frequently in the Gesar epic, and sometimes Gesar and his horse are depicted with the dignities in place of the windhorse. In this context the snow lion, garuda and dragon represent the Ling (wylie: Gling) community from which Gesar comes, while the tiger represents the family of the Tagrong (wylie: sTag rong), Gesar's paternal uncle.

The windhorse ceremonies are usually conducted in conjunction with the lhasang (wylie: lha bsang, literally "smoke offering to the gods") ritual,[9] in which juniper branches are burned to create thick and fragrant smoke. This is believed to increase the strength in the supplicator of the four nag rtsis elements mentioned above. Often the ritual is called the risang lungta, (wylie: ri bsang rlung ta), the "fumigation offering and (the throwing into the wind or planting) of the rlung ta high in the mountains." The ritual is traditionally "primarily a secular ritual" and "requires no presence of any special officiant whether public or private." The layperson entreats a mountain deity to "increase his fortune like the galloping of a horse and expand his prosperity like the boiling over of milk (rlungta ta rgyug/ kha rje 'o ma 'phyur 'phyur/).

In the Shambhala teachings of Chogyam Trungpa

The late 20th-century Tibetan Buddhist master Chogyam Trungpa incorporated variants of many of the elements above, particularly windhorse, drala, the four animals (which he called "dignities"), wangtang, lha, nyen and lu, into a secular system of teachings he called Shambhala Training. It is through Shambhala Training that many of the ideas above have become familiar to westerners.

Heraldry

The wind horse is a rare element in Heraldry. It is shown as a strongly stylized flying horse with wings. The most common example is the coat of arms of Mongolia. In Europe, the equivalent symbol is the Pegasus.

windhorse: Tibetan: "lungta" Lung: "wind" Ta: "horse". "Invoking Secret Drala is the experience of raising windhorse, ["Ta"]: raising a wind of delight and power and riding on, or conquering, that energy. ... The personal experience of this wind comes as a feeling of being completely and powerfully in the present. The horse aspect is that, in spite of the power of this great wind, you also feel stability. you are never swayed by the confusion of life...excitement or depression. You can ride on the energy of your life. So windhorse includes...practicality and discrimination, a natural sense of skill. This quality is like the four legs of a horse, which make it stable and balanced... you are not riding an ordinary horse, you are riding windhorse."

"Self existing energy." "The 'wind' principle of basic goodness is strong and exuberant and brilliant. It can actually radiate tremendous power in you life. But at the same time, basic goodness can be ridden, which is the principle of the 'horse'. By following the disciplines of warriorship, particularly the discipline of letting go, you can harness the wind of goodness. In some sense the horse is never tamed - basic goodness never becomes your personal possession. But, you can invoke and promote the uplifted energy of basic goodness in you life. You begin to see how you can create basic goodness for yourself and others on the spot, fully and ideally, not only on a philosophical level, but on a concrete physical level. When you contact the energy of windhorse, you can naturally let go of worrying about your own state of mind and you can begin to think of others.

...Experiencing the upliftedness of the world is a joyous situation, bit also brings sadness ...It is like falling in love...you feel both joy and sorrow...The warrior who experiences windhorse feels the joy and sorrow of love in everything he does."

"From the echo of meditative awareness you develop a sense of balance, which is a step toward taking command of your world. you feel that you are riding in the saddle, riding the fickle horse of mind. Even though the horse underneath you may move, you can still maintain your seat. As long as you have good posture in the saddle, you can overcome any startling or unexpected moves. And wherever you slip because you have a bad seat, you simply regain your posture; you don't fall off the horse. In the process of losing your awareness, you regain it because of the process of losing it. slipping in itself, corrects itself. You begin to feel highly skilled, highly trained."

"The principle of meditative awareness...gives you a good seat on this earth..." "You are completely grounded in reality. One may say, 'How do I know that you are not over reacting to situations?' You can say, simply, 'My posture in the saddle speaks for itself.' At this point you begin to begin to experience the fundamental notion of fearlessness."

(See also "Bowing")