World ruler

The world ruler: The sociopolitical exercise of power by the Adi Buddha

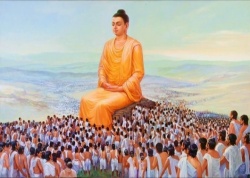

In his political function the Adi Buddha is a world ruler, a “universal sovereign”, a “world king” (dominus mundi), an “emperor of the universe”, a Chakravartin. The early Buddhists still drew a distinction between a Buddha and a Chakravartin. Hence we can read in the legends of Buddhism’s origins how a holy man prophesied to Shakyamuni’s father that his wife, [[Maya-Devi soon bear an enlightened one (a Buddha) or a world ruler (Chakravartin), depending upon which this son would as a young man later decide to be. Gautama chose the way of the “spiritual” Buddha and not that of the “worldly” Chakravartin, who in the customs of his time also had to act as military leader alongside his political duties.

In Mahayana Buddhism this distinction between a dominus mundi and an enlightened being increasingly disappears, yet the Chakravartin possesses exclusively peaceful characteristics. All his “conquests”, reports the scholar Vasubandhu (fourth or fifth century C.E.), are nonviolent. The potentates of the world voluntarily and unresistingly subject themselves on the basis of his receptive radiation. They bow down before him and say: “Welcome, O mighty king. Everything belongs to you, O mighty king!” (quoted by Armelin, n.d., p. 21). He is mostly incarnated as an avatar, as the reincarnation of a divine savior, who should lead humanity out of its earthly misery and into paradise.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, especially in the Kalachakra Tantra, the Chakravartin is the successful result of the sexual magic rites we describe above. The “asocial” yogi, who during his initiatory phase hangs around cemeteries and with prostitutes like an outlaw has become a radiant king whose commands are obeyed by nations. The Time Tantra thus reveals itself to be a means of “conquering” the world, not just spiritually but also in power political terms; in the end the imperial idea of a Chakravartin includes the whole universe. Boundlessly expanding energies are accumulated here in a single being (the “political” Adi Buddha).

The eminently political character of the Indian Chakravartin makes him an ideal for Tibetan Lamaism, which could first be realized, however, in the person of the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617-1682). Before the “Great Fifth” ascended the throne, the arch-abbots of the individual Lamaist sects — whether voluntarily or by necessity aside — accorded the title of world ruler only to the mighty Chinese Emperors or, depending on the political situation, to individual Mongolian Khans. The Tibetan hierarchs themselves “only” claimed the role of a Buddha, an enlightened being, whom they nonetheless considered superior to the Chakravartin. The Fifth Dalai Lama, who combined in his person both worldly and spiritual power for the first time in the history of Tibet, was also still careful about publicly describing himself as Chakravartin. This could have provoked his Mongolian allies and the “Ruler on the Dragon Throne” (the Emperor of China). Such restraint was a part of the diplomacy of the Tibet of old; or rather, since the Dalai Lamas were during their enthronement handed the highest symbol of universal rule — the “golden wheel” — they were the “true”, albeit hidden, rulers of the world, at least in the minds of the Tibetan clergy. The worldly potentates of neighboring states were at any rate accorded the role of a protector.

We shall come to speak in detail about whether such cosmocratic images still excite the imagination of the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama in the second part of our study. In any case, the Kalachakra Tantra which he has placed at the center of his ritual politics contains the phased initiatory path at the end of which the Lion Throne of a Chakravartin rears up.

The “golden wheel” (chakra) is regarded as the world ruler’s coat of arms and gave him his name, which when translated from Sanskrit means “wheel turner”. Already at birth a Chakravartin bears a signum in the form of a wheel on his hand and feet as graphic proof of his sovereignty. In Buddhism the wheel symbol was originally understood to be the “teaching” (the Dharma) and the first “wheel turner” was no lesser than the Buddha himself, who set the “wheel of Dharma” in motion by distributing his truths among the people and among the other beings. Later, in Mahayana Buddhism, the golden wheel already indicated “The Great Circle of Power and Rule” (Simpson, 1991, p. 45). The Chakravartin was referred to as the “King of the Golden Wheel”. This is the title given to the “Emperor of Peace”, Ashoka (273–236 B.C.E.), after he had united India and with great success converted it to Buddhism; but is also a name which the Dalai Lama acquires when the “golden wheel” is presented to him during his enthronement.

A Buddhist world ruler grasps the “wheel of command”, symbol of his absolute force of command. In the older texts the stress is primarily on his military functions. He is the supreme commander of his superbly armed forces. As “king and politician”, the Chakravartin is a sovereign who reigns over all the states on earth. The leaders of the tribes and nations are subordinate to him. His epithet is “one who rules with his own will, even the kingdoms of other kings” (quoted by Armelin, n.d., p. 8). He is thus also known as the “king of kings”. His aegis extends not just over humanity, but likewise over Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, wrathful kings, gods, demons, nagas (snake gods), masculine and feminine deities, animals and spirits. Of his followers he demands passionate devotion to the point of ecstasy.

The seven “valuable treasures” which are available to a Chakravartin are:

(1) the wheel,

(2) the wish-granting jewel,

(3) the wonder horse,

(4) the elephant,

(5) the minister,

(6) the general, and

(7) the princess.

Sometimes, the judge and the minister of finance are also mentioned. [3]

Opinions differ from text to text about the spatial expansion of power of the Chakravartin. Sometimes he “only” controls our earth, sometimes — as in the Kalachakra Tantra — the entire universe with all its suns and planets. This is — as we have already shown — described in the Abhidharmakosha, the Buddhist cosmology, as a gigantic wheel with Meru the world mountain as its central axis. The circumference is formed by unscaleable chains of mountains made of pure iron, from whence the name of this cosmic model is derived — Chakravala, that is, ‘iron wheel’. The Chakravartin is thus sovereign of an “iron wheel” of astronomical proportions.

In terms of time, the Buddhist writings nominate varying lengths of reign for the Chakravartin. In one text, as a symbol of control the supreme regent carries in his hand a golden, silver, copper, or iron wheel depending upon the eon (Simpson, 1991, p. 270). This corresponds to the Indo-European division of the ages of the world in which these become increasingly short and “worse” nearer the end. For this reason, world rulers of the golden age reign many millions of years longer than the ruler of the iron age. The Chakravartin also represents the Kalachakra deity, he is the bearer of the universal “time wheel” and hence the “Lord of History”.

As lawmaker, he monitors that human norms stay in keeping with the divine, i.e., Buddhocratic ones. “He is the incarnate representation of supreme and universal Law”, writes the religious studies scholar, Coomaraswamy (Coomaraswamy, 1978, p. 13, n. 14a). As a consequence, the world ruler governs likewise as “protector” of the cosmic and of the sociopolitical order.

As a universal guru he sets the “wheel of the teaching” (Dharmachakra) in motion, in memory of the famous sermon by the historical Buddha in the deer park of Benares, where the “first turning of the Wheel of the Word” took place (Coomaraswamy, 1979, p. 25). As a consequence, the Chakravartin is the supreme world teacher and therefore also holds the “wheel of truth” in his hands. As cosmic “wheel turner” he has overcome the “wheel of life and death” through which the unenlightened must still wander.

In the revolutionary milieu of the tantras (since the fourth century C.E.), the political, war-like aspects of the “wheel turner” known from Hinduism became current once more, to then reach — as we shall see — their most aggressive form in the Shambhala myth of the Kalachakra Tantra. The Chakravartin now leads a “just” war, and is both a Buddha (or at least a Bodhisattva) and the glorious leader of an army in one person. The “lord of the wheel” thus displays clear military political traits. As the emblem of control the “wheel” also symbolizes his chariot with which he leads an invincible army. This army conquers and subjugates the entire globe and establishes a universal Buddhocracy. The Indian religious scholar, Coomaraswamy, also makes reference to the destructive power of the wheel. Like the discus of the Hindu god Vishnu, it can shave off the heads of the troops of entire armies in seconds.

Destruction and resurrection are thus equally evoked by the figure of the Chakravartin. He therefore also appears at the intersection of two eras (the iron and the subsequent golden age) and represent both the downfall of the old and the origin of the new eon. This gives him marked apocalyptic and messianic characteristics. He is incarnated as both world destroyer and world redeemer, as universal exterminator and universal savior.