Difference between revisions of "Shambhala and the Prague Thangka: The Myth's Visual Representation"

(Created page with " Shambhala and the Prague Thangka: The Myth's Visual Representation Lubos Belka, Masaryk {{Wiki|University}} This photo essay addresses the visu...") |

|||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[File:Shambhala 047.jpg|thumb]] | ||

| Line 4: | Line 5: | ||

| + | [[Shambhala and the Prague Thangka]]: The [[Myth's Visual Representation]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Lubos Belka]], |

| − | + | Masaryk {{Wiki|University}} | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | This photo essay addresses the [[visual]] aspects of the [[Shambhala]] [[myth]] in Inner {{Wiki|Asia}}, in particular [[Mongolia]], [[Amdo]], and [[Buryatia]]. The last [[Shambhala king]], [[Raudracakrin]], is usually depicted in two basic [[forms]]: either as a quiet, [[Nirvanic]] [[ruler]] on the | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[throne]] in [[Kalapa]], the [[capital of Shambhala]], or as an [[angry]], [[wrathful]], and merciless {{Wiki|military}} commander in the last {{Wiki|battle}} of [[Shambhala]]. | ||

| − | + | A [[Shambhala]] [[thangka]] in the National Gallery in [[Prague]], [[Czech Republic]], represents ninety-eight years of [[Raudracakrin's]] {{Wiki|rule}} (2326-2424) 1, depicted in [[Kalapa]] in the upper part whereas the lower part depicts the last {{Wiki|battle}} prophesied to unfold in the year 2424. The [[subjects]] of this analysis are primarily | |

| + | |||

| + | the [[wrathful forms]] of [[Raudracakrin]], the last [[ruler]] ([[kalki]]) of [[Shambhala]], and special [[attention]] is paid to his armor, lance, and [[vajra]] ([[ritual]] weapon). His [[name]] literally means "the [[angry]] one with the [[wheel]]," and for this [[reason]] we must also analyze the | ||

| + | [[wheel]], whose [[nature]], as well as [[Raudracakrin's]], is ambivalent. Its quiet [[form]] [[symbolizes]] [[teaching]] (Skt. [[dharma]]), and its [[wrathful form]] represents a weapon, which is used in {{Wiki|battle}} or as an instrument of torture in [[hell]]. | ||

| − | + | Drawing on [[visual]] sources, some of which have not been published before, this essay provides a cultural-historical analysis of the [[Shambhala]] | |

| − | + | [[myth]] in the Tibeto-Mongolian interface with the [[Prague]] [[thangka]] serving as a focal point. The photo essay in this special issue of Cross-Currents on "[[Buddhist Art]] of | |

| − | + | [[Mongolia]]" is devoted to the [[Prague]] [[thangka]] for two [[reasons]]: the [[thangka]] has been neither described nor published outside the [[Czech | |

| − | + | Republic]], and the depiction of [[Shambhala]] ([[including]] the [[Prague]] [[thangka]]) is the [[subject]] of the article by Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz in this issue.2 Theoretically, the essay is | |

| − | + | situated in the research field of global history. Its main aim is to explore aspects of {{Wiki|cultural}} transfers and entanglements among [[Tibet]], | |

| − | + | [[Mongolia]], [[Western]] {{Wiki|Europe}}, and the [[Russian empire]] in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but it also addresses different modes of representing the [[Shambhala]] [[myth]] in contemporary [[Tibet]], [[Mongolia]], and [[China]] | |

1 The exact dates are not consistent in [[Tibetan Buddhist]] sources. See Wallace (2004, 2011); Kollmar-Paulenz (1992-1993, 2008). | 1 The exact dates are not consistent in [[Tibetan Buddhist]] sources. See Wallace (2004, 2011); Kollmar-Paulenz (1992-1993, 2008). | ||

| − | 2 Both contributions were originally presented at the thirteenth seminar of the International Association for [[Tibetan Studies]] held in July 2013 in Ulaanbataar, [[Mongolia]]) and are closely related. | + | 2 Both contributions were originally presented at the thirteenth seminar of the International Association for [[Tibetan Studies]] held in July 2013 in [[Ulaanbataar]], [[Mongolia]]) and are closely related. |

| + | |||

| + | In 1986, the {{Wiki|Asian}} Collections of the National Gallery in [[Prague]] gained a significant asset: a large [[thangka]] depicting Shambhala.3 It is | ||

| − | + | helpful to view the painting with [[knowledge]] of several basic facts. Its place and time of origin are not known. The {{Wiki|Asian}} Collections of the National Gallery purchased the | |

[[thangka]] from a private [[person]], a [[Prague]] citizen, and it is impossible to find out when and from what source the painting was acquired by its last [[owner]]. The circumstances surrounding the [[thangka's]] discovery thus remain obscure. It is therefore necessary to apply [[methods]] of comparative [[art]] history in order | [[thangka]] from a private [[person]], a [[Prague]] citizen, and it is impossible to find out when and from what source the painting was acquired by its last [[owner]]. The circumstances surrounding the [[thangka's]] discovery thus remain obscure. It is therefore necessary to apply [[methods]] of comparative [[art]] history in order | ||

| − | to determine its provenance. Nora | + | to determine its provenance. Nora Jelinkova mentions [[Tibet]] as the place and the "[[latter]] half of the 19th century" as the time of origin in the first short publication about the painting in the [[Czech]] [[language]] (Jelinkova 1998, 37); however, these claims remain uncertain. |

| Line 56: | Line 68: | ||

The [[thangka]] in the Musee National des [[Arts]] Asiatiques-Guimet is typologically different; its {{Wiki|dimensions}} are 112 cm x 222.5 cm. The main difference is in the composition: this [[thangka]] from [[Tibet]] is oriented not vertically with the {{Wiki|capital city}} of [[Shambhala]] [[Kalapa]] in the upper part of the picture and the last {{Wiki|battle}} taking place below, but horizontally with the scenes next to each other (see Rhie and Thurman 1996a, 158-159, figs. 43, 43.1). | The [[thangka]] in the Musee National des [[Arts]] Asiatiques-Guimet is typologically different; its {{Wiki|dimensions}} are 112 cm x 222.5 cm. The main difference is in the composition: this [[thangka]] from [[Tibet]] is oriented not vertically with the {{Wiki|capital city}} of [[Shambhala]] [[Kalapa]] in the upper part of the picture and the last {{Wiki|battle}} taking place below, but horizontally with the scenes next to each other (see Rhie and Thurman 1996a, 158-159, figs. 43, 43.1). | ||

| − | A similarly composed [[thangka]] in [[Buryatia]] has appeared in two publications (Terentyev 1983; Vanchikova 2008, 34-35). Neither author, however, mentions its precise location and size. An analogous depiction with {{Wiki|dimensions}} of 175.3 cm x 196.9 cm is part of the private Zimmerman [[Family]] Collection (see Rhie and Thurman 1996a, 482, fig. 238). Another similar, almost square, large-format painting is located in [[Erdene Zuu Monastery]] in [[Mongolia]] (inv. no. 65-854); its size is 156 cm x 168.5 cm. This [[thangka]] has been published twice (Frings, Muller, and Pleiger 2005, 374, fig. 415; Vanchikova 2008, 153). | + | A similarly composed [[thangka]] in [[Buryatia]] has appeared in two publications (Terentyev 1983; Vanchikova 2008, 34-35). Neither author, however, mentions its precise location and size. An analogous depiction with {{Wiki|dimensions}} of 175.3 cm x 196.9 cm is part of the private Zimmerman [[Family]] |

| + | |||

| + | Collection (see Rhie and Thurman 1996a, 482, fig. 238). Another similar, almost square, large-format painting is located in [[Erdene Zuu Monastery]] in [[Mongolia]] (inv. no. 65-854); its size is 156 cm x 168.5 cm. This [[thangka]] has been published twice (Frings, Muller, and Pleiger 2005, 374, fig. 415; Vanchikova 2008, 153). | ||

A similar depiction is located in the [[Tibetan monastery]] of [[Kumbum]] but, unlike the painting at [[Erdene Zuu Monastery]], it lacks the {{Wiki|battle}} scenes; only the city of [[Kalapa]] is depicted. It is shown in Badmazhapov (2003, 52), but its {{Wiki|dimensions}} are not specified. Other [[thangkas]] in [[Kumbum]] include the {{Wiki|battle}} scenes and thus represent the [[traditional]] depiction of [[Shambhala]] with [[Kalapa]] and the last {{Wiki|battle}} (Badmazhapov 2003, 59). | A similar depiction is located in the [[Tibetan monastery]] of [[Kumbum]] but, unlike the painting at [[Erdene Zuu Monastery]], it lacks the {{Wiki|battle}} scenes; only the city of [[Kalapa]] is depicted. It is shown in Badmazhapov (2003, 52), but its {{Wiki|dimensions}} are not specified. Other [[thangkas]] in [[Kumbum]] include the {{Wiki|battle}} scenes and thus represent the [[traditional]] depiction of [[Shambhala]] with [[Kalapa]] and the last {{Wiki|battle}} (Badmazhapov 2003, 59). | ||

| − | All of the abovementioned [[thangkas]] are historical works whose origins date back several centuries. Recent depictions are represented by the [[Tibetan painting]] located in [[Namgyal Monastery]] in [[India]]. It is shown, again without its {{Wiki|dimensions}}, in Harrington (1999, 39). Typologically, this painting belongs to the vertical portrayals that include [[Kalapa]] and the last {{Wiki|battle}}, as well as all the remaining depictions. A historical [[thangka]] of the same composition and [[typology]], but unknown {{Wiki|dimensions}}, is located in the {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[monastery]] of Shankh. The first probably bears the closest resemblance to the [[Prague]] [[thangka]]; the second has fewer similarities. A final example is from the Dahortsang Collection; it is shown, but its {{Wiki|dimensions}} are not specified, in Brauen | + | All of the abovementioned [[thangkas]] are historical works whose origins date back several centuries. Recent depictions are represented by the [[Tibetan painting]] located in [[Namgyal Monastery]] in [[India]]. It is shown, again without its {{Wiki|dimensions}}, in Harrington (1999, 39). Typologically, this |

| + | |||

| + | painting belongs to the vertical portrayals that include [[Kalapa]] and the last {{Wiki|battle}}, as well as all the remaining depictions. A historical [[thangka]] of the same composition and [[typology]], but unknown {{Wiki|dimensions}}, is located in the {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[monastery]] of Shankh. The | ||

| + | |||

| + | first probably bears the closest resemblance to the [[Prague]] [[thangka]]; the second has fewer similarities. A final example is from the Dahortsang Collection; it is shown, but its {{Wiki|dimensions}} are not specified, in Brauen | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ====References==== | ||

| − | |||

Badmazhapov, Tsyren-Bazar, ed. 2003. Ikonografia Vadzhrayany [[[Iconography]] of the [[Vajrayana]]]. {{Wiki|Moscow}}: Dizajn. Informacija. Kartografija. | Badmazhapov, Tsyren-Bazar, ed. 2003. Ikonografia Vadzhrayany [[[Iconography]] of the [[Vajrayana]]]. {{Wiki|Moscow}}: Dizajn. Informacija. Kartografija. | ||

| Line 118: | Line 138: | ||

About the Curator | About the Curator | ||

| − | Lubos Belka is {{Wiki|Associate Professor}} in the Department for the Study of [[Religions]] at Masaryk {{Wiki|University}}. The research for and publication of this article was supported by a 2017 grant (NOVYMHIR - MUNI/A/0819/2017) from the Department for the Study of [[Religions]], Faculty of [[Arts]], Masaryk {{Wiki|University}}, Brno, [[Czech Republic]]. | + | [[Lubos Belka]] is {{Wiki|Associate Professor}} in the Department for the Study of [[Religions]] at Masaryk {{Wiki|University}}. The research for and publication of this article was supported by a 2017 grant (NOVYMHIR - MUNI/A/0819/2017) from the Department for the Study of [[Religions]], Faculty of [[Arts]], Masaryk {{Wiki|University}}, Brno, [[Czech Republic]]. |

Latest revision as of 06:29, 2 January 2021

Shambhala and the Prague Thangka: The Myth's Visual Representation

Masaryk University

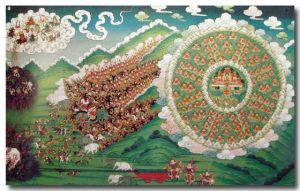

This photo essay addresses the visual aspects of the Shambhala myth in Inner Asia, in particular Mongolia, Amdo, and Buryatia. The last Shambhala king, Raudracakrin, is usually depicted in two basic forms: either as a quiet, Nirvanic ruler on the

throne in Kalapa, the capital of Shambhala, or as an angry, wrathful, and merciless military commander in the last battle of Shambhala.

A Shambhala thangka in the National Gallery in Prague, Czech Republic, represents ninety-eight years of Raudracakrin's rule (2326-2424) 1, depicted in Kalapa in the upper part whereas the lower part depicts the last battle prophesied to unfold in the year 2424. The subjects of this analysis are primarily

the wrathful forms of Raudracakrin, the last ruler (kalki) of Shambhala, and special attention is paid to his armor, lance, and vajra (ritual weapon). His name literally means "the angry one with the wheel," and for this reason we must also analyze the

wheel, whose nature, as well as Raudracakrin's, is ambivalent. Its quiet form symbolizes teaching (Skt. dharma), and its wrathful form represents a weapon, which is used in battle or as an instrument of torture in hell.

Drawing on visual sources, some of which have not been published before, this essay provides a cultural-historical analysis of the Shambhala

myth in the Tibeto-Mongolian interface with the Prague thangka serving as a focal point. The photo essay in this special issue of Cross-Currents on "Buddhist Art of

Mongolia" is devoted to the Prague thangka for two reasons: the thangka has been neither described nor published outside the [[Czech

Republic]], and the depiction of Shambhala (including the Prague thangka) is the subject of the article by Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz in this issue.2 Theoretically, the essay is

situated in the research field of global history. Its main aim is to explore aspects of cultural transfers and entanglements among Tibet,

Mongolia, Western Europe, and the Russian empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but it also addresses different modes of representing the Shambhala myth in contemporary Tibet, Mongolia, and China

1 The exact dates are not consistent in Tibetan Buddhist sources. See Wallace (2004, 2011); Kollmar-Paulenz (1992-1993, 2008).

2 Both contributions were originally presented at the thirteenth seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies held in July 2013 in Ulaanbataar, Mongolia) and are closely related.

In 1986, the Asian Collections of the National Gallery in Prague gained a significant asset: a large thangka depicting Shambhala.3 It is

helpful to view the painting with knowledge of several basic facts. Its place and time of origin are not known. The Asian Collections of the National Gallery purchased the

thangka from a private person, a Prague citizen, and it is impossible to find out when and from what source the painting was acquired by its last owner. The circumstances surrounding the thangka's discovery thus remain obscure. It is therefore necessary to apply methods of comparative art history in order

to determine its provenance. Nora Jelinkova mentions Tibet as the place and the "latter half of the 19th century" as the time of origin in the first short publication about the painting in the Czech language (Jelinkova 1998, 37); however, these claims remain uncertain.

The record card of the Asian Collections of the National Gallery of Prague includes the following important facts: registration number Vm 5951; size: height 195 centimeters and width 135 centimeters; painted with mineral colors on a canvas that consists of two pieces sewn together; torn in several

places; the color is wiped off in patches and secondary retouches are apparent; the overall tone is bluish-green. The painting is glued onto the canvas and, according to an information card in the gallery was "glued to a frame in 1998 (removable acrylate and lath)." The thangka was cleaned and restored by

the professional team of the National Gallery before it was exhibited in 2014. The thangka has been on exhibit several times in the Czech Republic but nowhere else. The first exhibition was held in Prague in 1986, the year it was

acquired, in the Exhibition of New Acquisitions of the Asian Collections of the National Gallery; it was displayed again in an exhibit titled, "Orientalni umeni" (Oriental art) in 1990 in Litomerice. In October 1998, the thangka was placed in the Permanent Exhibition of the Asian Collections of the National Gallery, and it has rarely been exhibited since then. Photographs of the painting have never been published apart from the color reproduction in Gyaltso (2012) and Jelinkova's abovementioned brief book in Czech.

About fifteen thangkas that are either similar or identical to the Prague thangka have been identified. All of them have been published in books, articles, or specialized websites. One well-known thangka comes from Mongolia and is located in Ulaanbaatar (Zanabazar Museum of Fine Art). Its dimensions are 81 cm x 60 cm; it has been published four times (see Tsultem 1986, fig. 37); Beguin and Dashbaldan 1993, 189-191; Berger and Bartholomew 1995, 182; Fleming and Lkhagvademchig 2011, 514-517).

A thangka located in New York's Rubin Museum of Art (acc. no. F1997.38.2) measuring 59.7 cm x 39.4 cm has been described in detail (Rhie and Thurman 1996b,

Shambhala and the Prague Thangka

484-485, fig. 197) and published online. Another well-described thangka is located in Basel's Museum der Kulturen; its dimensions are 64.5 cm x 46 cm (Essen and Thingo 1989, 205, fig. 125).

One of the oldest thangkas, first described by Giuseppe Tucci, is found in Zurich's Volkerkunde Museum der Universitat (inv. no. 13090). Its dimensions are not specified; a reproduction has been made available only as a black-and-white photograph (see Tucci 1949, 598 [plates 211-213]).

The thangka in the Musee National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet is typologically different; its dimensions are 112 cm x 222.5 cm. The main difference is in the composition: this thangka from Tibet is oriented not vertically with the capital city of Shambhala Kalapa in the upper part of the picture and the last battle taking place below, but horizontally with the scenes next to each other (see Rhie and Thurman 1996a, 158-159, figs. 43, 43.1).

A similarly composed thangka in Buryatia has appeared in two publications (Terentyev 1983; Vanchikova 2008, 34-35). Neither author, however, mentions its precise location and size. An analogous depiction with dimensions of 175.3 cm x 196.9 cm is part of the private Zimmerman Family

Collection (see Rhie and Thurman 1996a, 482, fig. 238). Another similar, almost square, large-format painting is located in Erdene Zuu Monastery in Mongolia (inv. no. 65-854); its size is 156 cm x 168.5 cm. This thangka has been published twice (Frings, Muller, and Pleiger 2005, 374, fig. 415; Vanchikova 2008, 153).

A similar depiction is located in the Tibetan monastery of Kumbum but, unlike the painting at Erdene Zuu Monastery, it lacks the battle scenes; only the city of Kalapa is depicted. It is shown in Badmazhapov (2003, 52), but its dimensions are not specified. Other thangkas in Kumbum include the battle scenes and thus represent the traditional depiction of Shambhala with Kalapa and the last battle (Badmazhapov 2003, 59).

All of the abovementioned thangkas are historical works whose origins date back several centuries. Recent depictions are represented by the Tibetan painting located in Namgyal Monastery in India. It is shown, again without its dimensions, in Harrington (1999, 39). Typologically, this

painting belongs to the vertical portrayals that include Kalapa and the last battle, as well as all the remaining depictions. A historical thangka of the same composition and typology, but unknown dimensions, is located in the Mongolian monastery of Shankh. The

first probably bears the closest resemblance to the Prague thangka; the second has fewer similarities. A final example is from the Dahortsang Collection; it is shown, but its dimensions are not specified, in Brauen

References

Badmazhapov, Tsyren-Bazar, ed. 2003. Ikonografia Vadzhrayany [[[Iconography]] of the Vajrayana]. Moscow: Dizajn. Informacija. Kartografija. Beguin, Gilles, and Dorjin Dashbaldan. 1993. Tresors de Mongolie, XVIIe-XIXe siecles [[[Treasures]] of Mongolia, seventeenth-nineteenth centuries]. Exhibition catalogue, Musee national des arts asiatiques-Guimet, Paris, Nov. 26, 1993-March 14, 1994. Paris: Reunion des musees nationaux.

Belka, Lubos. 2007. "Kalachakra and the Twenty-Five Kulika Kings of Shambhala: A Xylograph from Prague." Religio 15 (1): 125-138.

. 2009. "The Shambhala Myth in Buryatia and Mongolia." In Proceedings of the European Society for Central Asian Studies, edited by Tomasz Gacek and Jadwiga Pstrusinska, 19-30. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

. 2014. "Sambhala a konec sveta" [[[Shambhala]] and the end of the world]. In Konec sveta [The end of the world], edited by Lubos Belka, 64-94. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

Berger, Patricia, and Terese Tse Bartholomew, eds. 1995. Mongolia: The Legacy of Chinggis Khan. San Francisco: Asian Art Museum.

Bernbaum, Edwin. 1980. The Way to Shambhala. New York: Anchor Books.

Brauen, Martin. 2004. Dreamworld Tibet: Western Illusion. Bangkok: Orchid Press.

Essen, Gerd-Wolfgang, and Tsering Tashi Thingo. 1989. Die Gotter des Himalaya: Buddhistische Kunst Tibets [The gods of the Himalaya: Tibetan Buddhist art]. Vol. 1. Munich: Prestel.

Fleming, Zara, and J. Lkhagvademchig Shastri, eds. 2011. Mongolian Buddhist Art: Masterpieces from the Museums of Mongolia, Vol. 1, parts 1-2: Thangkas, Appliques and Embroideries. Chicago, IL: Serindia Publications.

Frings, Jutta, Claudius Muller, and Henriette Pleiger, eds. 2005. Dschingis Khan und seine Erben: Das Weltreich der Mongolen [[[Wikipedia:Chinggis Khaan|Chinggis Khaan]] and his heirs: The Mongol empire]. Exhibition catalogue, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn. Munich: Hirmer.

Gyaltso, Lenka. 2012. "Sambhala." In Zivot v asijskem palaci: Laska, luxus, zahalka [[[Life]] in an Asian palace: Love, Luxury, Idleness], edited by Petra Poliakova, 18-21. Prague: Narodni Galerie.

Harrington, Laura, ed. 1999: Kalachakra: Namgyal Monastery. Rome: Tibet Domani.

Jelinkova, Nora. 1998. "Sambhala." In Mistrovska dila asijskeho umenize sbirek Narodnigalerie v Praze [The masterpieces of Asian art from Prague's National Gallery collections], edited by Ladislav Kesner, 33-52. Prague: Narodni Galerie.

Kollmar-Paulenz, Karenina. 1992-1993. "Utopian Thought in Tibetan Buddhism: A Survey of the Sambhala Concept and Its Sources." Studies in Central and East Asian Religions 5 (6): 78-96.

. 2008. "Uncivilized Nomads and Buddhist Clerics: Tibetan Images of the Mongols in the 19th and 20th Centuries." In Images of Tibet in the 19th and 20th Centuries, vol. 2, edited by Monica Esposito, 707-724. Paris: Ecole Frangaise d'Extreme-Orient.

. 2019. "Visualizing the Non-Buddhist Other: A Historical Analysis of the Shambhala Myth in Mongolia at the Turn of the Twentieth Century." CrossCurrents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 33-57.

Meinert, Carmen, ed. 2011. Buddha in the Yurt: Buddhist Art from Mongolia. Munich: Hirmer.

Rhie, Marylin M., Robert A. F. Thurman. 1996a. Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet (Expanded Edition). London: Thames and Hudson.

. 1996b. Worlds of Transformation: Tibetan Art of Wisdom and Compassion. New York: Tibet House.

Shambhala and the Prague Thangka

Roerich, Georges. [1932] 1967. "Studies in the Kalacakra." Reprinted in Izbrannye Trudy [Selected works], edited by Yuri Rerikh [Jurij N. Roerich], 151-164. Moskva: Nauka.

Terentyev, Andrey. 1983. "On the Shambhala Image." Buddhists for Peace: The Journal for the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace 5 (2): 49-51. Tsultem, Nyam-Osoryn. 1986. Mongol'skaya natsional'naya zhivopis' "Mongol zurag" [[[Wikipedia:Mongolian|Mongolian]] national painting—"Mongol zurag”]. Ulaanbaatar: Gosizdatel'stvo.

Tucci, Giuseppe. 1949. Tibetan Painted Scrolls III: Description and Explanation of the Tankas. Rome: La Libreria dello Stato. Vanchikova, Tsymzhit P., ed. 2008. Zemlia Vadzhrapani: Buddizm vZabaikale [[[Vajrapani's]] land: Buddhism in the Transbaykalia]. Moscow: Dizajn. Informatsija. Kartografija.

Wallace, Vesna A., trans. 2004. The Kalacakratantra: The Chapter on the Individual Together with the Vimalaprabha. New York: Columbia University Press.

. 2011. The Kalacakra Tantra: The Chapter on Sadhana Together with the Vimalaprabha Commentary. A Study and Annotated Translation. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies.

About the Curator

Lubos Belka is Associate Professor in the Department for the Study of Religions at Masaryk University. The research for and publication of this article was supported by a 2017 grant (NOVYMHIR - MUNI/A/0819/2017) from the Department for the Study of Religions, Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic.