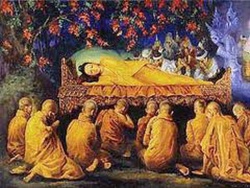

Ceremonies for the departed

Brahmanism at the time of the Buddha taught several contrasting, even conflicting ideas about what happens to a person after they die; that they go to heaven, that they are dispersed among the elements, that they become plants or that they join their ancestors, the fathers (pitāmahā), in some kind of shadowy afterlife. All these notions are mentioned in the Vedas. The last of them was probably the most widely accepted as it is the one mentioned most frequently in the Tipiṭaka. During the Buddha's time there seems to have been only the beginning of an idea that one's postmortem state, whatever it might be, was determined by one's moral or immoral behavior while alive. Everyone, it was assumed, went to the world of the fathers. Some days after the funeral the oldest son, directed by a brahman, performed a ceremony called the sraddha (Pāḷi saddha, A.V,273; D.I,97) in which small balls of dough (piṇḍa) and other food were offered to the departed person as this invocation was made: `May this offering benefit our ancestors who are dead and gone. May our ancestors dead and gone enjoy this offering.' (A.V,269). The belief was that this food would be received by the departed and help to sustain them. Gifts were then given to the brahmans directing the ceremony. Only a son could perform the saddha rite, which was one of the main reasons people so strongly desired to have a son (A.III,,43). Performing this ceremony was one of `the five offerings' (pañcabalim) every person was expected to make (A.II,68). Evidence of the enduring nature of Indian spirituality is that this ceremony, little changed, is still done today by Hindus. As with many other contemporary beliefs, the Buddha ethicized Brahmanical ideas about the afterlife, and shifted the practices associated with them from the material to the psychological. He reinterpreted the `fathers' (pita) as the `hungry spirits' (peta) and said that only greedy, immoral or wicked people might get reborn as such unhappy beings (A.I,155). A good and kindly person, he said, would probably be reborn as a human or in heaven, rather than the world of the fathers. When the brahman Janussoni asked if it were really possible for the departed to receive and benefit from the material offerings made to them the Buddha replied that this could only happen if they had been reborn as a hungry spirit (A.V,269). However, it seems unlikely that the Buddha would have believed the rather primitive notion that material offerings could actually be conveyed to another dimension. More likely the Buddha was using skillful means, adopting the questioner's standpoint in order to speak to him or her in terms they could understand. In this case he probably did so because although he would not have accepted that material things can be conveyed to another world, he could see that Janussoni's desire to do so was based on good intentions -love, gratitude and concern for his departed ancestors. When the Buddha was addressing his instructed disciples he would say that the best way they could give their departed relatives something that would benefit them would be to lead a good and moral life here and now. Once he said: `If a monk should wish, "Those departed relatives and ancestors of mine who I recall with a calm mind, may they enjoy great fruit and benefit," then he should be one who is filled with virtue, who spends time in solitude, dedicated to meditation and calmness of mind.' (A.V,132). The Buddha's idea seems to have been that if you wish to give happiness to your departed loved ones lead a life of kindness and integrity. In keeping with this interpretation the Kathāvatthu specifically denies that the departed can receive or benefit from material things offered to them (Kv. XX,4). In traditional Buddhists countries today people will do good deeds, usually making offerings to monks, and then in a simple ceremony dedicate the merit they have created to their departed loved ones. Although people often believe they actually `transfer the merit' to the departed person this is a misunderstanding of Buddhist doctrine. See Ghosts and Transference of Merit.

Significance of the Ritual Concerning Offerings to Ancestors in Theravada Buddhism', P. D. Premasiri, in Buddhist Thought and Ritual, 1991.