The Influence of Confucianism and Buddhism on Chinese Business

Introduction

Buddhism and Confucianism have had an impact on China for about two thousand years. In fact, Chinese culture is rooted in these two philosophies and their impact on Chinese life and economics is deep. According to Marx (2001:95), the country’s philosophical traditions are a part of its being, while Gernet (1995) recognizes the contributions of Buddhism to Chinese culture, particularly its influence on many aspects of Chinese life, thought, literature, language, art and science (1995:471). Ambler (2003) finds that "Confucianism has been guiding people´s behavior since Han Dynasty" (206BC-220AD) (Ambler 2003). So Confucianism and Buddhism have affected and continue to affect the way Chinese people think and operate.

Unfortunately, the two philosophies were suppressed in the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but in recent years, Buddhism and Confucianism have been booming in China. In 2005, a nationwide survey about Chinese people´s religion and beliefs was carried out by Liu Zhongyu from the Research Center for Religion and Culture, East China Normal University. In this research, 5000 questionnaires were sent to people over the age of 16, about 91.2% of whom responded. The findings demonstrated that about 300 million people have different religious beliefs (Buddhism, Taoism, Catholicism, Christianity and Muslim, etc, Buddhism being the dominant part); indeed, 62% of the respondents aged between 16 and 39 claimed to have such beliefs Generally speaking, compared with two decades ago, people with faith are becoming younger and younger. The main reason given for religious belief is to meet spiritual needs, and Prof. Liu´s survey reveals that Chinese people have begun to emphasize spiritual life with the rise of living standards and the rapid lifestyle.

Nowadays, in different areas of public life, from government to business, religion is being promoted. For example, in a recent speech, President Hu Jintao suggested that religion, including Buddhism, can help ease tensions between the haves and the have-nots (Dexter 2008:51). In addition, there seems to be a growing trend towards worshipping Buddha and Confucius among Chinese business people, especially Chinese merchants, also known as Confucian merchants. The contrary trend appears with temple monks trying to connect Buddhism with business. For example, Shi Yongxin, the Abbot of Shaolin Temple (the origin of Chinese Buddhism) is called a CEO because he is the first person who has made the connection between traditional Chinese Buddhism and business. Abbot Shi runs many Shaolin gongfu schools inside China and abroad. Chen Xiaoxu, the former female Founding President of Beijing Shibang Advertising, became a Buddhist nun in February 2007. Shi Yongxin, Chen Xiaoxu and Confucian merchants all made people think a lot about the influence of Buddhism on business. These examples demonstrate the strong link between spiritual and material life in contemporary China.

Profile of Confucianism and Buddhism principles

The teachings of Buddhism and Confucianism promote harmony to achieve inner peace. Gernet (1995) explained the second of Buddhism's six principles of harmony like this: whether sightseeing or on business, or visiting others, people should observe the local customs and laws, to live in harmony (1995:52). On the other hand, Buddhism teachings emphasize silence and consider that "trouble exists from the mouth" (Chin 1998).

As for Confucianism, it considers harmony as the basis of the family, proposing that harmony can make fortune (prosperity). At the same time, harmony is the final goal of good guanxi(关系) which lies at the heart of all human relationships and connections and is based on five codes of Ethics: ruler-subject, father-son, husband-wife, older brother-younger brother, and relationships with friends. As Chen Ming Jer (2003) [1] explains: Confucianism governs every relationship including those of business. So while guanxi(关系) includes kinship, demographic relationships, relationships with colleagues, and paternalistic leadership (Chen, in Samovar ed. 1999), it is also a key in determining the performance of business (Luo 2000 v). Confucianism preaches diligence and obedience, and it also teaches people to use Li (礼, ritual or rites) to communicate. In short, it "sets out the correct form of behavior in a given situation so as to preserve harmony and face" (Ambler 2003).

Influenced by the two faiths, the Chinese are calm, silent, united and obedient people who have strong and close knit families and help each other to overcome difficulties.

Chinese scholars and merchants abroad

Since China opened up in 1978, the Chinese economy began to integrate into the global economy, and "increasing numbers of Chinese began to go overseas, in small numbers at first, but in significant numbers from the mid-1990s".[2] More and more students and skilled workers were sent abroad by the government, while others were motivated to further their studies and to work away from mainland China. The total number of overseas Chinese is about 35 million, of which 5 million went abroad after 1978, according to Liang (accessed online) [3]. About 80% of these Chinese immigrants have settled in Southeast Asia. A project carried out in 2007 reported [4] that 99% of overseas Chinese merchants run many low-technological, low-competitive and small-scale retail stores and restaurants or Chinese medical clinics. As for faith, they believe in Buddhism, Taoism and other religions [5]. Some overseas Chinese, who behave in accordance with Confucianism, pray to Bodhisattva for safety and wealth, and donate to the temple.

In fact, after China´s opening up, a new type of immigration began to emerge: the movement of educated or skilled people to search for better opportunities in living standards. The first hosting countries for overseas Chinese students or scholars were the U.S.A., the U.K., Australia, Canada, Germany, France and Japan [6]. These students prepare themselves in the areas of science, technology and business. China has been attracting back these students with no tax and other benefits to work in education, government or their own business since the 1990s. According to Skeldon (2004, accessed online), with its rapid economic development, China will need to import labor from migrants who are living abroad, who left home to get rich, marry and settle down. This has been the newest trend of Chinese overseas professionals returning to mainland. It was Europe, on the other hand, that saw the less skilled workers rushing to open up businesses like manufacturing and trading, running restaurants and stores also. According to the Europe Times (accessed online) [7], there are 1.5 million (a very small number) of Chinese overseas settling in Europe, and about half of these originated from Wenzhou and Qingtian, (Zhejiang province, East China), famous for business and the hometown of many Chinese gone overseas.

China´s economy is growing fast and it has become the factory of the world. The economic success of China benefits from, or is closely associated with, Confucianism and Buddhism. The Chinese business community abroad has also achieved success and reflects Confucian thought in its organizational structure, which is firmly based on the family. As Chen points out, "For Chinese living outside the PRC, the family-based business model is strong" (Chen, 2003; accessed online).

Confucianism and Buddhism on Chinese business in China

Our survey (see Appendix), carried out in 2007, reflects the effects of Confucianism and Buddhism on Chinese business in China. Our larger aim was to find out what is happening in respect of English and international business in China, and to this end, a questionnaire was developed in English and Chinese which was given to employees in 59 companies by email or in paper form, in China. Companies were classified according to their location, international or national profile, products and the type of company, such as foreign, joint venture, state-owned, or private company. Some 550 questionnaires were given in Chinese (350) and English versions (200). 297 questionnaires were received, 288 of which were considered valid.

The classification of the respondents was based on gender, age, nationality, academic background, profession and employer. The respondents who were employees in corporations or language school were all Chinese except three, who were Brazilian, and about 90% of these respondents were aged from 20 to 39. As for the position of the employees in the companies, the majority were technicians (81), followed by Management (71) and Marketing (62), then Public Relations (11) and Accounting (3). As for academic background, the largest number had Bachelor Degrees (163), while the smallest number held Doctorates (4). The remaining respondents divided themselves between those holding a Master's (66) and those with no academic degree (63).

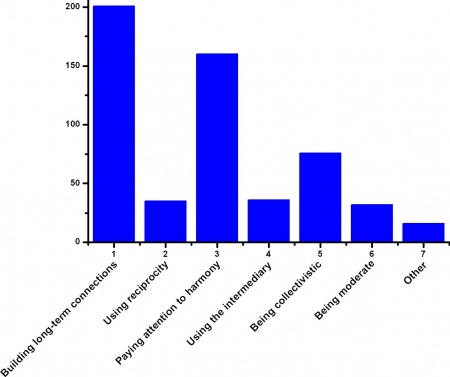

Below we present some results of our survey which reveal the influence of the two philosophies. These results have not been previously published. First of all, in relation to ways of communicating which were deemed to be effective by our population (Figure 1), we found that around 69.8% of the respondents answered building long-term connections (guanxi, 关系), while nearly 55.6% responded with paying attention to harmony. These results demonstrate how overwhelmingly important long-term connections and harmony are considered amongst this group.

When questioned about the cultural values considered important for successful business in Chinese markets (Figure 2), our results revealed that 68.7% of the respondents selected interpersonal harmony, 62.6% considered trust, 50.8% included collectivism, and 46.5% chose guanxi (关系), followed by endurance, social status, thrift, face and others. These results demonstrate how much importance is attributed to the role of interpersonal harmony, trust, collectivism and guanxi (关系) in successful business in China.

In response to the question about the contributions of Confucianism and Buddhism to business in China (Figure 3), the respondents considered tolerance (important Chinese cultural value) with 47.9% answers as the most important aspect, followed by the cooperative principle and politeness, loyalty and the win-win principle, showing the importance of these values in Chinese business. No matter where they are located, Chinese employees from foreign, joint-venture or state-owned companies, share the same cultural values and determine the way they deal with conflict management (Shi 2003). These cultural values make Chinese people work harder. Confucianism and Buddhism principles like harmony, the cooperative principle, politeness, the win-win principle, loyalty and endurance are exercised in the way they do their business.

The case of Aveiro

In the next section, we will look at the influence of Confucianism and Buddhism on Chinese business abroad on the basis of a small study carried out in Aveiro, Portugal. It will look more specifically at harmony, silence and face-saving through the analysis of short examples of interaction which took place in the most typical form of Chinese business found in our region: Chinese shops. We will demonstrate the influence of religion on Chinese business with some concrete examples from the real world.

Context

Aveiro is the capital city of the District of Aveiro with about 57,000 inhabitants, located in Northwest Portugal. It is a commercial city with an important seaport on the Atlantic coast. In an interview carried out on the 26th Feb 2008, Manuel Silva, an officer in charge of immigrant services of Aveiro, we found that there are about 749 Chinese immigrants in the region of Aveiro, of which 275 are business people. Others are students in regular schools. In total, there are 13 Chinese shops and 4 Chinese restaurants in the city of Aveiro, including seven medium-sized shops in the main street. (interestingly, a Chinese couple opened a Japanese restaurant in the city centre). Both shops and restaurants are well-placed in the city, being central and easy to reach, and have a good number of customers. Chinese business units tend to be small or medium-sized because of the limited purchasing Power.

The immigration of Chinese business people dates from the mid 1990s, "taking advantage of the process of Chinese economic integration in the community and choosing Portugal based on business opportunities" (Rocha & Maria, 2006). Those Chinese merchants who have settled here run family businesses and can be divided into three groups: those that run shops; those that run restaurants and those who successfully manage both. In recent years, the economy of Portugal has been less favorable and many owners of restaurants have changed to open up shops to reduce their costs. The owner/employees work long hours (8-21; seven days a week).

Buddhism and Confucianism in Aveiro

As will be shown below, after interviewing 12 Chinese business people, we found that the influence of both philosophies is integrated in all of these people´s lives. They keep the same Chinese way of life, despite living abroad and learning other languages and cultures. The examples of the influence of Buddhism and Confucianism which we will present were observed and collected from the seven shops and three restaurants, and particularly from one shop where the first author spent one week as an assistant in order to observe more closely the relations and dialogues in the business context.

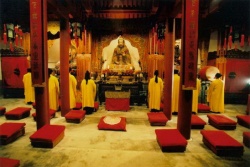

The first thing we notice is the decorations of the restaurants which, to western eyes, are markers of Chinese restaurants but, to their owners, are related to Buddhism (Figure 4). One restaurant put a Buddha statue at the front door for blessings. Scroll paintings and calligraphy of Buddhism and Confucianism sayings are shown there, such as tolerance and quietness. The Chinese shops sell statues of Buddha, pictures, scroll paintings and calligraphy about Buddhist and Confucian beliefs.

Influenced by the two religions, the Chinese business community is family-based and very close, although good relationships have been built with the local people, and some second generation Chinese immigrants have married Portuguese men/women. In recent years, a new trend has emerged with some Chinese business people taking on Portuguese employees in order to integrate into local culture and to facilitate communication. Chinese employers treat their employees as family members and respect them. To build a good relationship (guanxi, 关系), Chinese employers invite their employees to their home for dinner, even their Portuguese ones. Like other overseas Chinese merchants in Europe, the Chinese business persons in Aveiro are mostly from Qingtian or Wenzhou. Sharing the same hometown background, their interpersonal relationship is very good and they often help each other with money or services. Some of the owners are in fact relatives. An old Chinese proverb reflects their interdependence: "at home, people depend on their parents; outside home, people depend on friends". Their educational level is low. Most of them only have primary school education and some are unschooled.

When Chinese entrepreneurs are conducting their business, their attitudes toward their customers are patient, kind and inviting. They are always very quiet and the local people have never seen them quarrelling. In fact, from a Chinese perspective, quarrelling in public means losing mutual face and harmony. In an interview, Mr. Zhou, a restaurant and shop owner told us that his family has believed in Buddha for many generations and all his family members still pray to Buddha daily. There is a statue of Buddha on the shelf at reception in his restaurant. He also has a Buddhist name `Dao zhen´. Pointing out some characteristics on the scroll paintings and calligraphy of Buddhism on the wall, Mr. Zhou explained: silence (静, jing in Chinese pinyin) means doing things peacefully, not acting on impulse; tolerance means self-control; sweetness comes after Suffering. He prays to Buddha for security, health and fortune. Meanwhile, he donated money to building roads and a Buddhist temple in his hometown. His business behavior must follow the teachings of Buddha with a kind heart (良心, liangxin in Chinese pinyin). He must not do anything in business that disobeys his faith. He also added that if you believe in the teachings of Buddhism, Buddha will bless you, and he attributes the success of his business to these beliefs. Recently, his son and daughter-in-law opened a wholesale jewelry shop in Porto (the second biggest city of Portugal).

Since Chinese people are a close knit family, they do everything together, even having their business open all hours of the day, some of them including lunch at work. Young mothers usually take care of their babies in the shops. The Chinese are also a thrifty people, who do not spend much money on daily necessities, saving up their money, in many cases to send back to China to build their house and help their elderly parents. Confucianism and Buddhism both preach filial piety (孝, xiao in Chinese pinyin), and "being filial toward our parents is a virtue of our self-nature" (Ching 1998). It is common practice in the traditional Chinese family for up to four generations to live together and the younger generations show respect to the elder members of the family, who are the powerful decision-makers.

On the first day of practice in the Chinese shop, the author became familiar with the lady owner whose family runs both a restaurant and a shop. Her shop is located in the commercial center of the city with many customers. The following morning, she told me about how they deal with thieves:

- Owner: This morning, I caught a woman thief on the spot.

- Author: Did you call the police?

- Owner: No. I just asked her to take out the stolen things and let her go.

- Author: Why not?

- Owner: Useless.

In fact, episodes of shoplifting happen constantly in Chinese shops in Aveiro. The boss in one Chinese store told us that thieves often visit their shop, so it is customary to watch very closely what is going on. The Chinese owners seldom talk with their customers. If they catch a thief, they just ask him or her to leave the stolen things and let them go. This is understood as being in harmony with the local people. The Chinese business community seldom calls the police. They told us that it is useless to do so, because it would mean damaging the relationship between the local inhabitants and themselves (in other words, damage harmony), and also because of limited language skills and a traditional background which values keeping the problem inside the family, not making it public. This is the value of silence at work in Chinese culture. John (2006:65) points out that "Buddhism promotes a life centered on spiritual rather than worldly matters. Buddhists seek Nirvana (escape from reincarnation) through charity, modesty and compassion for others; restraint from violence, and general self-control". In the context of Chinese community, harmony is achieved and preserved, and harmonious ways are found for dealing with social relations and social problems. Maintaining social harmony can bring more wealth and `personal harmony is the best way to maintain dignity, self-respect, and prestige´ (Chen, in Samovar 1999: 304).

We found Chinese owners to be very patient. The majority of their customers are Portuguese. They use their limited Portuguese language skills to serve. One day, a lady came to exchange five large photo frames, which the shop owner carefully checked before putting them back into boxes. Then she allowed her customer to get the bigger-sized frames herself. When the Portuguese lady came back to the counter, she also asked the owner to wrap them up. The Chinese owner was patient in the service she provided, and the Portuguese lady went away with satisfaction. The owner told us the same thing happened every day. Confucianism and Buddhism require perseverance and patience, which should be exercised towards themselves, and, of course, towards others.

Bargaining is also a common occurrence in Chinese shops. Here is an example. The author went to another Chinese shop and pretended to buy a statue of Buddha there.

- Author: Hello!

- Owner: Hello!

- Author: How much is this Buddha?

- Owner: 0.75€ for other person, for you, 0.50€.

- Author: What does it mean?

- Owner: It is a smiling Buddha to bless you with financial success.

- Author: Do you believe in Buddhism?

- Owner: No. But many Chinese merchants do.

- Author: Thanks.

- Owner: That´s all right.

Politeness and guanxi (关系) are highly valued here. The owner knows that Chinese people like bargaining, so to maintain mutual face, she reduces the price first. She is patient and shows a positive face, like a friend. So as a customer, the author did not feel embarrassed in this shop although she had been looking around for a long time without buying anything. The owner treated the author as a friend because they are compatriots, and a harmonious relationship is maintained between them, revealing perhaps the Confucian tendency to keep up politeness or guanxi (.关系).

During the period of practice, the author also found that Chinese merchants seem only to trust their family members (insiders, 家里人), and indeed Confucian teachings preach trusting insiders and distrusting outsiders. For instance, the owner of the shop told me that they would go shopping in Vila do Conde where the Chinese business community is concentrated. The author asked him if she could go with them. He agreed. Then, next morning, when she arrived at work, she was told that he had already left. So, only a Portuguese employee and the author (outsiders, 外人) were left to work in the shop; they were surprised when another Chinese employee (a relative or insider), who worked in the boss´s restaurant, was sent to the shop to work (and watch over them) for the whole day.

Conclusion

In the exposition above, we have drawn attention to some aspects of Buddhism and Confucianism which underlie the contexts and practices of the overseas Chinese business community in Aveiro, most notably: harmony, guanxi (关系), silence and tolerance.

The values of guanxi (关系) are always present in the lives of the Chinese abroad. Because of their low educational background, these populations tend to be limited in their ability to communicate properly and integrate fully into the surrounding community. To date, for example, despite the importance of China as a growing world market and the existence of a strong local Chinese community, there has been no Chinese business person who is a member of Aveiro's Industrial and Commercial Association. Facing strong competition, Chinese business people should improve their communicative skills, break old rules (of silence) and be more open to feedback from the local community. In this way, not only would they participate more fully in local (entrepreneurial) society, but they would also become engaged in a more meaningful intercultural dialogue in which underlying attitudes and values, as well as their visible symbols, would become as valuable for exchange as the goods they sell.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal) for supporting this research (Reference: SFRH/BD/29248/2006).

=

Source

=

- [1] Summary of Ming Jer Chen´s Book in Chen (2003), Inside Chinese Business. www.quickmba.com/mgmt/intl/china/. Accessed 21/02/2008.

- [2] Skeldon, R. (2004). China: From Exceptional Case to Global Participant. www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=219. Accessed 21/02/2008.

- [3] "海外中国移民超3000万, 改革开放后移民约500万". (Overseas Chinese immigrants are more than 30 million, including about 5 million after China opened up.) backchina.com/newspage/2008/02/26/147724.shtml.Accessed 26/02/2008

- [4] "2007年世界华商发展报告郭招金" (2007) (Guo Zhaojin, "A Report on the Development of Chinese Trader in the World".). www.huaxia.com/xw/dl/2008/00746897_2.html. Accessed 14/02/2008.

- [5] 华商世界知多少? (2001). (How much do you know Chinese Trader?). www.js.cei.gov.cn/huashang/hsdh_h1p.htm. Accessed 13/02/2008.

- [6] "全球化与中国海外移民" (曾少聪) (Zeng Shaocong. Globalization and Oversea Chinese Immigrants ). iea.cass.cn/org/.Accessed 24/02/2008.

- [7] backchina.com/newspage/2008/02/27/147840.shtml.Accessed 27/02/2008

Bibliography

- Blommaert, J.& Verschueren, J. (ed.) (1991). The Pragmatics of International and Intercultural Communication. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese Face: Insights from Psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- Ch´en, K. (1964). Buddhism in China: a Historical Survey. Princeton & New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Chin, K. (1998). Understanding Buddhism. The Collected Works of Venerable Master Chin Kung, Australia.

- Gernet, J. (1995), Buddhism in Chinese Society: an Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Green, G. M. (2nd ed.) (1996). Pragmatics and Natural Language Understanding. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Li, T.B. & Moreira, G. (2007). "How not to Give Offence in the Chinese Marketplace", in Barker D.A. (ed.), Giving and Taking Offence. University of Aveiro, Portugal.

- Luo, Y.D. (2000). Guanxi and Business. London: World Scientific.

- Marx, E. (2001). Breaking through Culture Shock: What You Need to Succeed in International Business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Nyíri, P. & Saveliev, I. R. (2002). Globalizing Chinese Migration: Trends in Europe and Asia. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

- Rocha, T. & Maria, B.(2006). A comunidade de negócios chinesa em Portugal catalizadores da integração da China na economia global. Oeiras: Instituto Nacional de Administração.

- Shi, Yongpeng. (2003), Culture and Conflict Management in Foreign-invested Enterprises in China: an Intercultural Communication Perspective. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Tu, W.M. (ed.) (1996). Confucian Traditions in East Asian Modernity: Moral Education and Economic Culture in Japan and the Four Mini-Dragons. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press.

- Wierzbicka, A. (1991). Trends in Linguistics: the Semantics of Human Interaction. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Wild, J.J.& Wild, Kenneth L. (2006). International Business: the Challenges of Globalization. New Jersey: Upper Saddle River.

Articles on the Web

- Chen, Ming Jer (2003). Inside Chinese Business. www.quickmba.com/mgmt/intl/china/. Accessed 21/02/2008.

- Dexter, R. (2008). China´s Spiritual Awakening. In Businessweek, January 21. businessweek.com/ Accessed 24/01/2008

- McGowan, C. (2004). Tales and Grice's Cooperative Principle. In English 2100: Oral Narrative in the Contemporary South. www.acs.appstate.edu/~mcgowant/grice.htm. Accessed 15/07/ 2007.

- Ritter. T. (2003). The Cooperative Principle. www.classicaldressage.com/zen/articles/a_2.html. Accessed 15/07/2007.

- Skeldon, R. (2004). China: From Exceptional Case to Global Participant. www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=219. Accessed 21/02/2008.

- When Opium Can Be Benign (2008). www.economist.com/countries/China/. Accessed 17/02/ 2008.

About the authors

Tian bo Li completed her MA in English studies at the University of Aveiro (Portugal) in 2005. Her MA research and dissertation were on the subject of English In China, and she is currently doing her PhD at the University of Aveiro, funded by the FCT (the Portuguese Foundation of Science and Technology), on The Role of English in International Business: the Case of China, under the supervision of Gillian Moreira, Assistant Professor at the same university. Gillian Owen Moreira holds a PhD in Culture from the University of Aveiro, where she is a member of the English Department and teaches in the fields of Cultural and Intercultural Studies. Her research interests focus on intercultural relations, European language policies and the politics and culture of English in the world.

Email address of author: tianbo@ua.pt or tian.bo.li@hotmail.com

Authors’ addresses

Correspondence relating to this paper should be sent to Tianbo Li.

Tian bo Li

Departamento de Línguas e Culturas

Universidade de Aveiro

3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal.

E-mail address: tianbo@ua.pt

Gillian Owen Moreira

Departamento de Línguas e Culturas

Universidade de Aveiro

3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal.

E-mail address: gillian@ua.pt