The avatar Buddha

by Suhotra Swami

Siddhartha Gautama was the blessed and beautiful prince of the Sakyas, a royal family descended from the Suryavamsha (the Solar Dynasty of ancient Indian kings). He had always been carefully sheltered from the distresses of life by his father, King Shuddhodana. In Kapilavastu, his capital near the Himalayan foothills, the king built three palaces for his son, one specially designed to be comfortable in the cold season, another for the hot season, and the third for the monsoon. These palaces towered in ornate splendour above beautiful gardens adorned with lotus ponds.

The prince was always surrounded by a host of lovely damsels who rendered him all kinds of personal service; they entertained him day and night with dance, music and games that were suited to every occasion and season. Prince Siddhartha wore only the finest cloth imported from Varanasi, a city which even today remains famous for its silk. His body was perfumed with the pulp of sandalwood. Day and night, a white parasol was held over his head. Even the servants in his palaces were fed sumptuously, so that the prince would not see want in others. The reason for all this pampering was that when the prince was born, a famous sage named Asita predicted that if Siddhartha became aware of the miseries of existence, he would renounce the world and establish a great religion (dharma). "Out of compassion for suffering humanity,", said Asita, ".....this prince will lead many people on the way to a holy life. Thus he will be a chakravartin, one who turns the wheel of dharma.

" King Shuddhodana, fearing the loss of his only son to asceticism, did his royal best to insure Siddhartha would never learn the meaning of the word suffering. But the outcome of the prince's life was already cast; after all, the name Siddhartha means "one whose aim is accomplished." Once, not long after his twenty ninth birthday, Prince Gautama went for a chariot drive along the royal road towards the palace park. As usual, he was accompanied by an escort of guards and attendants whose specific duty was to shield the prince from even the slightest unpleasantness. Nonetheless, on that day, the young man's eyes fell upon the frail, bent figure of a sad looking toothless man, so withered by age that he could hardly stand, his face pallid and his eyes devoid of lustre. When he inquired from an associate the reason for the decrepit man's plight, he was shocked to learn that it was simply due to the passage of time, and that given enough time, everyone would experience the misery of old age.

The prince returned to the palace in a gloom. He pondered how foolish it was for men to pass their time in the joys of the senses when in the end they would be reduced to the same condition of stark, trembling helplessness as he'd seen today.

King Suddhodhana, observing his son's moroseness, ordered punishment for the escort of guards and attendants, thinking they'd failed in their duty. He then arranged for a special program of entertainment for the prince, and after a few days' time, it appeared that Siddhartha was his same jovial self again. But the impact of seeing that old man had shaken his inner composure.

On another occasion not long thereafter, Siddhartha Gautama chanced to see a man groaning and writhing in the throes of some terrible sickness. He again became depressed when he was told that disease was inevitably suffered by all beings in the material world.

And though it seemed that the prince once more shook off the grips of melancholia, on a third chariot ride he came upon a corpse being carried to the cremation grounds. Learning that death is the ultimate misfortune from which there is no escape, Siddhartha became inwardly restless. A profound yearning arose within him for release from the sufferings imposed upon all beings by the implacable laws of nature. Lastly, Prince Siddhartha met a sannyasi, a shaven headed renunciate who wore a simple robe of saffron colour and carried nothing except a water pot and a danda (stick).

The prince was mystified by the saintly man's aura of inner peace and, ordering his chariot to stop, inquired from the monk the reason for his adopting this way of life. "O prince," answered the monk, "seeing the never ending miseries of worldly existence, I have renounced all family ties for gaining the permanent peace and happiness of a tranquil mind." And so did Siddhartha Gautama's disquieted mind come to find the doorway to new hope. Henceforward the prince's whole attitude towards life changed. When, soon after his meeting with the sannyasi, he was informed that his beautiful young wife, Yashodhara, had given birth to a son, he exclaimed, "Yet another bond! Let this child be called Rahula" (a diminutive form of Rahu, the name of a malignant planet). The delights of the senses had become his disgust; he vowed, "I shall go forth into the struggle of subduing my senses. Therein only shall my mind find happiness."

In the middle of the night after the birth of his son, the prince awoke to view in the light of the full moon what he later called "the wretchedness of lust" around him: his female attendants, after celebrating Rahula's birth with song and dance into the late hours, had fallen asleep from exhaustion and lay in dishevelled and unseemly poses about the palace. Full of deep resolve to transcend the allurements of illusion that bind one to birth and death, Siddhartha Gautama left everything, cut off his hair and donned the robes of renunciation.

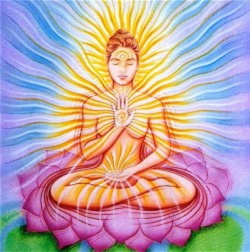

After six years of austerity and meditation, a wondrous insight dawned upon the prince as he sat under a Bodhi tree not far from the holy city of Gaya, sacred to devotees of Vishnu. He saw the darkness of the miserable material world dissolve into the light of divine knowledge, which revealed the true nature of all beings. Gazing upon them with the pure emotions of friendship, compassion and benevolence, Gautama saw clearly that although the living entities suffer in the whirlpool of samsara (repeated birth and death which is found in all species throughout the universe), they are of an essence sublime, like unto his own.

For seven days, Siddhartha Gautama sat absorbed in the ecstacy of transcendence. Four headed Brahma, the chief demigod of cosmic creation and the guru (teacher) of the sacred Vedas for the whole universe, then appeared before him. Hailing him as the "All seeing Buddha," Brahma requested that he preach a new dharma for the salvation of the fallen souls, "those lost in suffering, overcome by birth and decay." As described in the Mahavagga, the Buddha then "looked full of compassion with the Buddhic eye towards sentient beings all over the universe, and declared 'The door to the realm of the immortals is now wide open to all those who hear me.'"

Who is the Buddha?

There are many people, even among those claiming to be Buddhists, who think that the Buddha was an ordinary man who attained a rare level of self awareness. As a popular treatise on Buddhism explains, "The Buddha is not a God or a deity who one should pray to for some fulfilment in life. The Buddha is not an incarnation of God [nor] a prophet nor a messenger of God........He is a human being but a very special human being, one who has gained what we call 'Enlightenment'."

But in the Buddhist scriptures we find the Buddha him self declares otherwise. In the Donasutta he says, "I am not a deva (demigod), a gandharva (an angel), a yaksha (fierce guardian spirit), nor a human being." Yet, while declaring himself to be not a human being, does the Buddha deny that he is God, the Father of all beings? In the Mahavagga the Buddha says, "The Buddha looks with kind heart equally upon all beings, and they therefore call him 'Father'. To disrespect a father is wrong; to despise him is wicked." And in the Saddharma Pundarika, he clearly announces:

yam eva ham lokapita svayambhu

cikitsakah sarvaprajnan natah

"I am the Self born, the Father of the World, the Lord of All Beings and the Remover of Ills."

Moreover, the Buddha is addressed throughout the scriptures with titles asserting his divinity, such as Bhagavata (Supreme Person), Lokavid (Knower of All Worlds), Anuttara (the Unsurpassable) and Shasta Deva Manushyanam (Lord of Men and Demigods).

In Bhagavad Gita, the ancient Sanskrit text of the transcendental teachings of Sri Krishna to His disciple Arjuna, we find very similar titles of address. Krishna is called Bhagavan (Supreme Lord), Lokapita (Father of the Worlds), Svayamatma (Self Existing), Aja (Unborn), Sarva Loka Maheshvaram (Lord of all Planets and Demigods), and Buddhir Buddhimatam (the Enlightenment of the Enlightened Ones). In Bhagavad Gita, Krishna reveals to Arjuna that He is the original Vishnu, Who is worshipped as the Supreme Person by the followers of the Vedas. And in a Buddhist text, Lankavatara sutra, the Buddha is identified with the self same Vishnu.

The similarities of the portrayals of the Buddha in Buddhist scriptures and Sri Krishna in Bhagavad Gita has not gone unnoticed by scholars. K.N. Upadhyaya writes in "Studies in the History of Buddhism." In striking resemblance to Bhagavad Gita, the very form and atmosphere in which the Buddha appears in the Sad dharma Pundarika is astonishingly supernatural. Like the cosmic form of Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, he is depicted as shedding resplendent light, dazzling the enormous space from hell to the 18,000 regions of Buddhas."

It is a common figure of speech to refer to the qualities of a person as "nature", for example, "he is good natured", or "her nature is very shy." From Bhagavad Gita we learn that Krishna is the Eternal Supreme Person and His nature is all pervading pure consciousness, which is the support of everything. In other words, everything in existence is an aspect of God's nature, including our own selves.

Krishna's nature has two broad divisions: spirit and matter. Spirit, which is eternal, full of knowledge and bliss, is reality. Matter, which is temporary, full of ignorance and suffering, is the shadow of reality. It is also called maya, illusion.

In Bhagavad Gita, Krsna declares the living souls to be tiny individual aspects of His self effulgent spiritual nature. Unfortunately, some souls have fallen into the darkness of maya, Krishna's shadow, just as sparks fall out of a fire and lose their original brilliance. These fallen souls are conditioned by karma, the material law of action and reaction. The law of karma keeps them bound to the cycle of samsara in ever changing physical bodies, in which they must suffer birth, disease, old age and death.

A man's shadow always depends upon that man; he is never dependent upon his shadow. Similarly, though the material existence depends fully upon Krishna, He is independent from it, because He is purely spiritual. Therefore, when He descends into the material world to deliver the fallen souls, He is never conditioned by karma. He declares to Arjuna, "My appearance and activities in this world are always divyam (divine)." The cause for His descent is His infinite compassion for the souls suffering from ignorance.

Krishna's appearances in this world are like the endless flowing of the ocean waves they are countless, and they flow across all of the countless universes. Thus He appears throughout all history in unlimited forms called avatars (descended ones) to teach the way by which the lost souls may regain their eternality. Indeed, the very name Krishna means "He who nullifies (na) the cycle (krish) of repeated birth and death." According to time, place and circumstances, one avatar may teach spiritual knowledge in a way different from other avatars, but the aim is always the same to impel the fallen souls to somehow or other enter the stream of dharma.

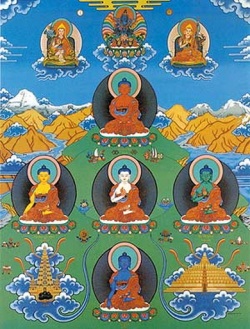

"He utters different discourses on dharma which may differ in their principles, to beings who differ in their mode of life and intentions and who wander amidst various speculations and perceptions, in order to generate the roots of good in them." (Sad dharma Pundarika) Out of countless avatars, ten are especially venerated in the Vedic scriptures. The ninth is the Buddha avatara, who appears in the beginning of the age called Kali yuga. There are four great ages of history that pass in cycles lasting for many thousands of years, just as the yearly seasons of spring, summer, fall and winter pass in cycles of many days. Five thousand years ago the earth entered Kali yuga, the Age of Darkness. The Buddha appeared about 2500 years ago. The Kali yuga will continue for another 427,000 years. But since the great Yugas or ages are cyclical, the Buddha will surely appear again in the future, as he has repeatedly in the past.

What was the Buddha's Mission?

There is a controversy about just what the Buddha taught that will be looked at in more depth shortly. But for the moment, some basic points of his teachings that are accepted by all Buddhists may be mentioned. The Buddha taught that material existence is dukha, miserable. He taught that there is samudaya, a cause of material existence; and because there is a cause, there is also nirodha, a way to remove material existence. That way is marga, the path of righteousness which the Buddha himself demonstrated by his own example. Two ancient Buddhist philosophers, Aryadeva and Chandrakirti, have written that the marga or path of the Buddha can be summed up in just two words: ahimsa (non violence) and shunyata (extinction). Non violence is one of 26 qualities that Sri Krishna counts as daivi sampat, "of the nature divine." The Buddha's mission of non violence in the cruel Kali age has won him the eternal praise of a great devotee of Krishna, Jayadeva Gosvami, who wrote in his famous Sanskrit work Gita Govinda:

nindasi yajna vidher ahaha shruti jatam

sadaya hrdaya darshita pashu ghatam

keshava dhrita buddha sharira

jaya jagadisha hare

"O Keshava (Krishna), Lord of the Universe, who have assumed the form of Buddha! All glories to You! O Buddha of compassionate heart, you decry the slaughtering of poor animals performed according to the rules of Vedic sacrifice."

At the time of the Buddha, wicked minded Brahmins (so called Vedic priests) who were devoid of spiritual knowledge were engaging in wholesale animal slaughter in the name of Vedic rituals. In previous ages, highly qualified priests and kings used to sometimes perform ritualistic animal sacrifices that promoted the souls of the animals to the human form of life. But since in the Age of Kali there are no such qualified performers of sacrifice, these rituals are therefore forbidden by the scriptures. Buddha appeared to enforce this prohibition by preaching the dharma of non violence.

For this reason, the Buddha is glorified in the Vedic scriptures: buddhas tu pashanda gana pramadat "May Lord Buddhadeva protect me from activities opposed to Vedic principles and from the madness that causes one to forget true Vedic knowledge and ritualistic action." (Srimad Bhagavatam 6.8.19)

There is an ancient poem, reputed to be the only text ever written by the Buddha himself:

"Creatures without feet have my love. And like wise those who have two feet; and those, too, who have many feet. Let creatures all, all things that live, all beings of whatever kind, see nothing that will bode them ill. May no evil come to them." Even as a child, Gautama Buddha rescued wounded animals from cruel hunters. And later when preaching the dharma, he made total renunciation of meat eating a fundamental part of his prescription for humanity.

In the Mahaparinirvana sutra, the Buddha declares, "The eating of meat extinguishes the seed of maha karuna (great compassion)." In the Lankavatara sutra he says, "For the sake of love of purity, the enlightened Buddhist should refrain from eating flesh, which is born from blood and semen. For fear of causing terror to living beings, let the enlightened Buddhist, who is disciplining himself to attain compassion, refrain from eating meat." He is cited in the Surangama sutra as saying, "The reason for meditating and seeking enlightenment is to escape from the suffering of life. But in seeking to escape from suffering ourselves, why should we inflict it upon others? Unless you can so control your minds that even the thought of brutal unkindness and killing is abhorrent, you will never be able to escape from the bondage of mundane life." Nowadays some Buddhists think that meat can be eaten if the animal was not specifically slaughtered for their enjoyment; even some bhikshus (monks) think that they may eat meat when it is given to them as alms, because they were not involved in the killing.

But such false ideas are refuted in the scriptures. In the Lankavatara sutra the Buddha enjoins, "It is not true that meat is proper food and permissible when the animal was not killed by himself, when he did not order others to kill it, when it was not specifically meant for him...meat eating in any form, in any manner and in any place is unconditionally and once and for all prohibited...Meat eating I have not permitted to anyone, I do not permit, I will not permit...........!"

Concerning those who nowadays teach that Buddhism permits meat eating, the Buddha declares in the Surangama sutra, "After my parinirvana (departure from this world into Nirvana)...different kinds of ghosts will be encountered everywhere deceiving people and teaching them that they can eat meat and still attain enlightenment................How can a bhikshu, who hopes to become a deliverer of others, himself be living on the flesh of other sentient beings?"

The Buddha's absolute prohibition of animal slaughter and meat eating corresponds completely to the definition of ahimsa in Bhagavad Gita. The Manu samhita, a code book of Vedic ethics, warnthat they who kill animals, as well as they who prepare the flesh for consumption, or sell it, or transport and distribute it, or eat it, are equally sinful. Besides ahimsa, the other vital feature of the way of the Buddha is shunyata, the extinction of the desire for material existence which in turn extinguishes repeated birth and death.

On this point, too, Buddha consciousness and Krishna consciousness agree. Srila Rupa Gosvami, a great philosopher and devotee of Krishna from the 16th century, has written

anyabhilashita shunyam

jnana karmady anavrttam

"The lust for gross sense enjoyment (e.g. meat eating, illicit sex, gambling and intoxication) as well as the finer, or subtle desires for mental speculation and fruitive action are to be made shunya (void)." In the ”Sutra of Forty two Sections (a Chinese compilation of 42 sayings of the Buddha), we find the means to shunyata is explained in exactly the same way: "The gross passions grow from the finer will to act; the will to act grows from the even finer speculations of the mind. When these are calmed, transmigration will cease."

Buddhists strive for Nirvana; the word nirvana literally means "to leave the forest of material existence." In the Vedic scriptures, the material world is often compared to a dark, frightening vana (forest). In the Dhammapada the Buddha preaches, "Cut down the whole forest of lust, not just one tree.

Danger comes out of the forest of lust; when you have cut down the forest of lust and its undergrowth, then, monks, you will be rid of the forest and freed."

In Bhagavad Gita (2.71-72), Krishna tells Arjuna, "A person who has given up all desires for sense gratification, who lives free from desires, who has given up all sense of proprietorship and is devoid of false ego he alone can attain real and lasting peace. That is the way of the spiritual and godly life, after attaining which a man is not bewildered. Being so situated, even at the hour of death, one can enter the spiritual realm (brahma nirvana)."

Here a point of controversy may be raised. Many Buddhists will argue that the concept of brahma nirvana taught in Bhagavad Gita has no place in Buddhism, because Brahman (the eternal spiritual realm) is contrary to Buddhist shunyata, which is neither spiritual nor material but simply nothingness or void. Furthermore, the Buddhist doctrine of shunyata denies the eternality of the soul: according to many Buddhist texts, existence is anatta (soulless) and the idea "I have a self" is false and must be overcome to attain Nirvana.

Four observations may be made to refute these dogmatic assertions.

1. The Buddha rejected the false ego, but not the real ego. He rejected the Brahman of the blind followers of doctrines, but not the real Brahman. If the Buddha intended to reject utterly and entirely the self or soul (atta in Pali, atma in Sanskrit), then why, in Digha nikaya does he say atta dipa vidharatha atta sharana ("keep the soul as your lamp and only shelter") and katam me sharanam attano ("I have made the soul my refuge")?

When the Buddha proclaimed anatma or soullessness, he was refuting the false doctrine of the soul propounded by the Brahmins of the karma kanda school, who were the same animal killers opposed to the Buddha's mission of ahimsa. According to them, the atma is meant to eternally enjoy the fruits of punya karma, or rituals yielding material pleasures in future lives. In other words, their concept of the soul was inseparable from the lust to enjoy matter.

It was this false impure soul, self or ego that the Buddha de cried; yet he affirmed the pure non material soul as the true self in which we should all take shelter. Therefore the ancient Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna observed that the Buddha taught both atman and anatman. In the same way, the Buddha rejected the hypothetical Brahman of the argumentative priests of the jnana kanda school, who thought it could be attained by mental speculation. But he told of personally knowing the true Brahman.

In the Tevijjasutta of the Digha nikaya, the Buddha meets two Brahmins, Bharadvaja and Vasettha, who are arguing about the nature of Brahman. Buddha asks them if they or their teachers had ever seen Brahman. Receiving a sheepish "no", Buddha compares the two Brahmins to a young man who loudly declares love for a woman he has never seen nor knows anything about.

"For Brahman I know," the Buddha tells them, "and the realm of Brahman, and the path that lead eth to it. Yea, I know it even as one who has entered the Brahman realm, and has been born within it." 2. The Buddha's mission was not to settle the philosophical disputes of his time, but to deliver the fallen souls.

At the time the Buddha began his mission, there were 62 schools of philosophy in India wrangling over endless metaphysical questions. He saw this doctrinal disputation to be a useless waste of time, and dissuaded his disciples from entering into such discussions. The path of the Buddha was a path of practical purification. The ability to comprehend abstract doctrines was not a qualification to follow his path. "All living beings ... either thoughtful or thoughtless are lead by me to the final Nirvana of the extinction of reincarnation." (ajracchedika prajna paramita sutra)

It was not the Buddha's mission to establish another theory of the soul, Brahman, God, etc., for these subjects had simply become the cause of heated quarrel. Questions on these themes he dismissed as avyakrta, "unanswerable". For this reason, the modern Buddhist's insistence that "the Buddha taught the doctrine of voidism, not the doctrine of positive spiritual existence" misses the simple fact that the Buddha taught no doctrine at all. "Buddhist doctrine", (e.g. shunyavada, vijnanavada, yogachara, shrautranika etc.) was developed after the time of the Buddha. That he taught no specific doctrine is illustrated in his meeting with the philosopher Vachgotta, who questioned the Buddha repeatedly whether he believed in the existence or non existenceof the soul. The Buddha remained silent until Vachgotta left. He later explained, "If I had answered, 'there is a soul', that would have only confirmed the doctrine preached by the Brahmins. If I had answered, 'there is no soul', that would have only confirmed the doctrine of those who say the self dies with the body."

3. The Buddha did not claim to teach the ultimate truth for all time, but only what the Buddhists of his time could understand. It would be foolish to insist that Buddhism is the last word in understanding the meaning of existence when the Buddha himself denied it. Once, when preaching to his disciples while sitting under a Simsapa tree, he was asked if there was more Truth than that he had revealed. He picked up some fallen leaves and asked if there were more leaves in his hand or in the tree. When his disciples responded, "There are more in the tree", he answered, "Similarly, there is unlimitedly more Truth than what I give you now."

4. The canonical Buddhist scriptures are questionable renditions of the Buddha's teachings.

Like the New Testament and Christ, the Buddhist scriptures were neither written by the Buddha nor written down in his lifetime by his disciples. Instead, his disciples committed his sayings to memory; but within 100 days of the Buddha's passing from this world there was a controversy between Upali, called "the keeper of the law", and Ananda, considered the disciple closest to the Buddha, over the correct wording of their master's sayings.

A great council of Buddhists was called a few months later to resolve the confusion, and another convened a century later, but it was not until almost 250 years after the Buddha's passing that the Buddhist king Ashoka forced a final revision of the still unwritten scriptures. In doing this, Ashoka purged many learned Buddhists who did not agree with his point of view. Only after this third council was the main body of Buddhist scriptures (Tripitaka) finally set down in writing. The Vedic scriptures, on the other hand, were passed down by a line of greatly realised spiritual masters since very ancient times. Thus the authenticity of the most important Vedic scriptures like the Bhagavad Gita, Upanisads, and Srimad Bhagavatam is unimpeachable. Therefore, the key to understanding the mission of the Buddha is best gotten from them.

The Buddha, Incarnation of Krishna

But one may ask, "How are we to understand the Buddha through the Vedic scriptures when he himself decried their authority? The Vedas teach of God; but Buddha is not known to have spoken about God. How can these contradictions be reconciled?"

The answer comes from A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami in his commentary to Srimad Bhagavatam 1.3.24: "At the time when Lord Buddha appeared, the people in general were atheistic and preferred animal flesh to anything else. On the plea of Vedic sacrifice, every place was practically turned into a slaughter house, and animal killing was indulged in unrestrictedly. Lord Buddha preached non violence, taking pity upon the poor animals. He preached that he did not believe in the tenets of the Vedas and stressed the adverse psychological effects incurred by animal killing. Less intelligent men of the age of Kali, who had no faith in God, followed his principle, and for the time being were trained in discipline and non violence, the preliminary steps for proceeding further on the path of God realisation. He deluded the atheists because such atheists following his principles did not believe in God, but they kept their absolute faith in Lord Buddha, who himself was an incarnation of God.

Thus the faithless people were made to believe in God in the form of Lord Buddha. That was the mercy of Lord Buddha: he made the faithless faithful to him." Indeed, in the Milindapanha, the Buddha preaches: "Rituals have no efficacy, prayers are vain repetitions and have no saving power. But to abandon covetousness, to become free of evil passions, and to give up all hatred and ill will, that is the right sacrifice and true worship." And in regards to sowing faith in the hearts of the faithless, he says in the Kashi Bharadvaja sutta : "My seed is faith" (shraddha bijam). There is certain evidence that faith in the Buddha as the Supreme Lord did sprout within the hearts of his sincere followers. In the Lankavatara sutra, the Buddha is exalted as nishthabhava param brahma, "the very existence of the Supreme Lord (param brahma)." The same scripture declares that the Buddha is known by the names Vishnu and Ishvara. Parambrahma, Vishnu and Ishvara are all names of Krishna found in the Bhagavad Gita.

In the Vajrayana (Diamond Vehicle) school of Buddhism, an often chanted prayer known as the avalokiteshvara mantra (the Spiritual Mantra of Great Compassion) weaves names of other avataras of Krishna such as Hari, Varaha and Simhashiramukha (He with the face of a lion, Nrsingha) together with various more common known names of Buddha. Thus, the dharma established by the Buddha gradually evolved into indirect devotion to Krishna, and led the followers of the Buddha to the chanting of Krishna's holy name, which is repeatedly stressed in the Vedic scriptures as being the yuga dharma, the only religion that can nullify the evil effects of Kali yuga.

As it is stated in the Brhan Naradiya Purana:

harer nama harer nama harer nama eva kevalam

kalau nasteva nasteva nasteva gatir anyatha

"There is no other way to reach the supreme goal of life in the Kali yuga than by chanting the holy name of Hari (Krishna)." The Diamond Vehicle was the last Buddhist school to develop in India before Buddhism was expelled from that country; it is interesting to note that this school, so obviously influenced by devotion to Krishna, is said to have begun in Bengal (eastern India).

For, beginning in the early 16th century of the Christian calendar, Bengal was the focus of a great upheaval of Krishna bhakti (devotion to Krishna) which burst forth upon that region from the city of Navadvipa, where Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu took His birth in A.D. 1486. Sri Caitanya's Movement

Indeed, Sri Caitanya was directly the cause for this sudden mass popularity of Krishna consciousness, which came to be known as the sankirtana movement. Sankirtana refers to the congregational chanting of the Hare Krishna maha mantra (Hare Krishna Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare) in large public processions with the accompaniment of musical instruments like drums and cymbals.

Sri Caitanya was a full manifestation of Lord Krishna in this world; a particularly wonderful characteristic of His was His personal beauty, which shone with the lustre of molten gold. Thus He was known as Gauranga (one whose bodily features are golden).

But like the Buddha avatara, Lord Caitanya's divinity was not revealed to the general mass of people until after he grew to be a young man. Throughout His early life He was looked upon as a very clever Brahmin boy, but not more. In an extraordinary parallel to the Buddha, Caitanya's divine symptoms did not appear until he made a pilgrimage to the holy city of Gaya.

The great transformation began when He met a sannyasi, Ishvara Puri, who initiated Him into the chanting of Krishna's holy name. He returned to Navadvipa in a tumult of spiritual ecstacy, and hence forward organised the sankirtana movement as the means to spread Krishna's name everywhere. Who ever heard the holy name of Krishna from the lotus like lips of Lord Caitanya was overwhelmed by the transcendental bliss of Krishna prema, love of Krishna.

Although it is for some reason not known to most Buddhists today, the Buddha also sometimes used the word prema (in Pali, pema) to describe the love that his disciples felt for him, a love that would sometimes move them to tears. But that love was a mere reflection compared to the intense spiritual emotions that Sri Caitanya used to display and invoke in the hearts of others.

This ecstacy is called viraha, or the mood of overwhelming separation from the beloved of the soul, Sri Krishna. The viraha mood was described by Sri Caitanya in the following words:

yugayitam nimeshena

chakshusha pravrishayatam

shunyayatam jagat sarvam

govinda virahena me

"My Lord Govinda (Krishna), because of separation from You, I consider even a moment a great millennium. Tears flow from my eyes like torrents of rain, and I see the entire world as void (shunya)." Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu taught that unless the soul's dormant love for Krishna, the Supreme Soul, is revived, it is extremely difficult to nullify material existence; but when the yearnings of love of God flood the heart, the captivating allurements of this world fade into nothingness. A Bengali scripture called Sri Caitanya bhagavata describes many of the pastimes of the Lord; one was the Mahaprakash, in which for 21 hours He revealed many of Krishna's avatar forms within His own person, including that of the Buddha.

When He was 24 years of age, He accepted the sannyasa order of life and travelled around India for 6 years, preaching Krishna consciousness; afterward, he remained at the holy city of Jagannatha Puri, on the East coast of India (Orissa), until His disappearance from this world in the forty eighth year after His appearance. Sri Caitanya Caritamrta, another Bengali scripture, reveals that during His tour through South India, He instructed many Buddhists in the chanting of the holy name of Krishna. Later, a great follower of Sri Caitanya named Virabhadra Goswami became famous in Bengal for his mass conversion of about 2500 Buddhist monks and nuns to the way of Krishna bhakti; they were known in the samkirtana movement as the Nedas (shaven headed ones), and became a great force in spreading the movement in Dakha (the city now known as Dacca, capital of Bangladesh).

The samkirtana movement continues to spread around the worldto all nations and cultures in the form of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), founded in 1965 by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. ISKCON is a non sectarian fellowship of people who are serious about following the stream of dharma to the ocean of nectar of devotion to Krishna. The stream of dharma flows through the whole universe, and, like a river that flows through different countries, is known by different names to different people: Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, etc. The ocean of nectar, which gives us the full taste of spiritual bliss for which we are always anxious, is made immediately available to anyone, regardless of race, caste, or creed, who simply takes the Great Mantra for Deliverance: