Cosmogonic Myths in Northeast India

Forces of Nature

by Baidyanath Saraswati

One of the most inscrutable mysteries confronting man is that of his own existence. Reflections of man’s place and purpose in the universe are found in all cultures at all times, but the ways of understanding are different. Profound answers have been sought through religion, science and popular wisdom.

Science and Scriptures

Two opposite paradigms have been constructed in the post-Renaissance European science and Christian scriptures: evolutionism and creationism.1 Evolutionism considers man to be a product of nature, moving progressively from simplicity to complexity, from unorganized to organized, from lesser to greater. Creationism holds god as an active agent in the creation of man and the universe. The opposition between the formulation of science and the Christian ideas of creation is more apparent than real, for both are structured around the homocentric view of the universe. From the viewpoint of science, man makes his own history and civilization. Protagoras, the Greek sophist, has said, "Man is the measure of all things." The Biblical account places man at the centre of the purpose of creation. Man alone is entitled for progress and salvation.

The eastern view counters the western homocentrism. This could be best illustrated by the Indian theory of elements. The basic assumption of this theory is that, like the rest of the material world, man is made up of elements, which after death disintegrate and dissolve into nature. The elements have been spiritually identified and metaphysically debated for thousands of years. The texts of the religio-philosophical traditions differ in respect of both identification and classification of elements. At the most general level, there are nine tattvas: prthvi (earth), jala (water), tejas (fire), vayu (air), akasa (sky), kala (time), dika (directions), atma (soul) and manas (mind). Of these, the first five are called bhutas and the last four dravyas. The gross and the subtle aspects of elements are differentiated. Traditional thinking leaps over the dichotomy: the reality of the subtler planes is responsible for the grosser planes, and at a higher level of understanding the distinction between the gross and the subtle gets obliterated.

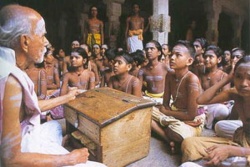

Oral Culture

In oral cultures, man’s fascination with the world is embodied in his language, myth and ritual, in fact, in everyday life of the whole community. Regrettably, there have been no systematic studies of this specific aspect of oral culture so far. However, a beginning has been made at the IGNCA in a consistent way.

Tribal Cosmogony

In the textual philosophical tradition, man has a fivefold constitution called bhutas — earth, water, fire, air and sky. It is not yet known whether such a conceptual category exists in the oral mythic tradition. In order to grasp its implicit philosophy, it is important to investigate and analyze the cosmogonic myths of a particular culture.

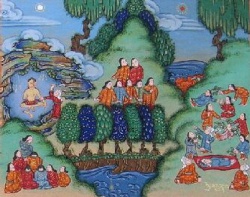

Tribal cosmogony refers to a variety of elements, some of which are self-existing and others created. The tribes of Arunachal Pradesh,2 for instance, refer to water, egg, cloud, rock, wood and the great personage as the self-existing elements of the first order. According to the tradition, from these were created elements of the second order: earth, sky, sun, moon, wind, fire and all living creatures. The third order of elements were then formed: colour, direction, form, smell, etc. The fourth order was attributed to knowledge.

A general description of the creation myths summed up in close identification of the elements now follows.

WATER

Before the earth was made, everything was water. There were two brothers who were supreme in the Sky. One day they said to each other, "When men are created, how will they live if there is nothing but water in the world?" There was a lotus flower growing in the sky. The brothers threw this down and immediately the water was covered with flowers. Then they called the winds from the four quarters. The east wind brought white dust and scattered it on the flowers. The west wind blew yellow dust, the south wind red dust and the north wind black dust. The wind blew the dust round and round and mixed it up together until the earth was formed. This is why the earth is made up of different colours.3

EGG

At first there was nothing but two eggs. They were soft and shone like gold. They did not stay in one place, but went round and round. At last, as they went round, they collided and both eggs broke open. From one came the earth, from the other the sky, her husband. When the sky made love to the earth, every kind of tree and grass and all living creatures came into being.4

CLOUD

At first there was no earth nor sky, but only cloud and mist. From it a woman was born; and since she came from the mist she was a sort of cloud. In time she gave birth to a girl and a boy. They had the appearance of snow. When they grew up they married each other and from them were born a girl called Inga (earth) and a son called Mu (sky). Inga was mud and Mu a cloud. These two also married and had a boy called Imbung (wind). When he was born he blew so strongly that he raised the cloud, his father, into the sky and dried up his mother, the mud. In this way heaven and earth were made.5

ROCK

At first there was nothing, nothing at all, but rocks and water. The first living beings were the rocks, but they were not as rocks are now: they were soft and could move about. From the rocks, a female rock was born. She married another rock and her first child was the fish. Then she gave birth to the big frog, and then the little frog, and then to the land frog. After that she gave birth to the insect which lives in water and then to another fish. Then she left her husband and went to the sky-village among the stars, where she married and had many children, and when she had borne them all, she died. The children prepared rice-beer for her funeral. When the millet was ready and they poured water over it, a great cloud arose, and from the cloud was born the mithun (bos frontalis). The mithun dug a great pit with his horns, and when water pour-ed into the pit, dry land appeared. After this the rocks became hard as they are today.6

WOOD

Everything was water — water as far as the eye could see. But above the water rose the tree Teri-Ramula. As time passed a worm was born in the tree and it began to eat the Wood. The dust fell into the water, year after year, until slowly, the world was formed. Then, at last, the tree fell to the ground. The bark on the lower side of the trunk became the skin of the world; the bark of the upper side became the skin of the sky. The trunk itself turned into rock. The branches became the hills.7

Great Personage

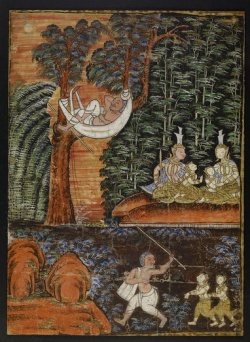

At first Kujum-Chantu, the earth, was like a human being. She had a head, arms and legs, and an enormous fat belly. The original human beings lived on the surface of her belly. One day it occurred to her that if she ever got up and walked about, everyone would fall off and be killed; so she died of her own accord. Every part of her body became a part of the world, and her eyes turned into the sun and the moon.8

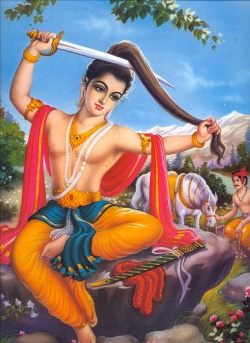

Some of these oral myths have parallels in textual myths. For instance, the tribal notion of creation from water, or from the cosmic egg, or from the transformation of some great personage, has a remarkable similarity with the vision of the classical texts. In the Hindu scriptures, one finds mention of the primeval ocean, Hiranyagarbha, the Golden Germ, and the sacrifice of Prajapati.9 The other motifs which the tribal cosmogonic myths share in common with the classical texts are lotus, snake, boar, fish, tortoise, mountain, and so on. Yet, apparently, there is no complete agreement between the tribal perception and the textual enumeration of the basic elements. Wood, for instance, is not an element in the classical texts, but finds a place in tribal oral myths. Interestingly, wood is one of the five elements in Chinese tradition.10

Another curious feature of tribal cosmogony is that in its vision of the phenomenal reality there is no single creator of the universe. There are creators for each specific element: Nili and Nipu, who were without form, made the earth and the sky respectively.11 Creation is a male-female principle, often brought about by marriage or sexual union.

Tribal Epistemology

Most tribes do not seem to have a clear notion of the fivefold constitution of the human body. Different tribes speak differently of the various elements responsible for man’s origin. Man has descended from the union of the earth and sky, who are regarded as wife and husband.12 Humankind is traced to the marriage between the daughter of the Sky-God and a spirit on Earth.13 The sun makes images of a man and woman from clay and puts a breath of life into them.14 The daughter of the lord of sky gave birth to a lump of flesh which was neither living nor dead. She dried it by the fire, and it soon burst open and bits of it scattered about the world and turned into human beings.15 In the beginning there was a great tree, from the berry of which grew a flower; out of this flower came a pair of human beings, the first man and woman.16 The first human beings came out of a gourd.17 Many of the first men and women came out of the tusk of an elephant.18

There are also stories of how the first human race was destroyed and a new race created. Seven suns destroyed humankind for its iniquity; then, after the world has been washed clean by rain, it was re-peopled with a new race.19 The first men were destroyed by fire and flood, and only one man and woman were saved; from them modern humanity has descended.20 The world was destroyed by flood and the tribe descended from a girl who was impregnated by the wind.21

Tribal myths deny the uniqueness of man insofar as his origin is concerned.22 There are no real distinctions between man, animal and spirit. A woman gives birth to twins, of whom one is human and the other a tiger; animals talk and often behave like men; of two brothers, one is the father of mankind and the other the father of spirits. There are many stories of marriage of human beings with gods, spirits, animals, as well as leaves, trees and, sometimes, even fire. Man is not unique even in the possession of knowledge.23 Primordial knowledge came to him from birds and animals. The knowledge of ritual is revelatory. The priests of all creatures were born at the beginning of creation. The implication of these myths is that the universal knowability lies with what could be called the Cosmic Intelligence, symbolized in the myth of the Cosmic Egg.

In contrast to the classical scriptural myths, tribal cosmogony asserts that the world was created in phases by a number of heavenly bodies and not by the one Creator-God, a single Supreme Being. It also makes no distinction between the creature and the creator. The early phases of creation were characterized by total integration of all that came into being. Everything that has been created has its own life, and hence there was no ontological difference between man and non-man. The truth of the unity of all experience and the harmony of all existence is expressed through the mythic confirmation of the relation between various elements of nature: the earth and sky are a divine couple and universal parents. Fire and whirlwind are brothers just as water and mist are brothers. But water and fire have always been enemies. Wind is the friend of fire against water and he fights the rain and drives it before him.

Man’s kinship with the earth and sky is reaffirmed by the eschatological belief that patterns of life on earth are the same as in heaven.24 Man lives on earth in the company of good and evil spirits, above whom rises the majestic figure of the sun-moon, Doini-Polo.25 The sun-moon was created after the wiyus (spirits) and, according to some traditions, later even than mankind.26 Water27 is believed to be under the control of the spirit; some dwell in streams and rivers; others are in the sky, making the world hot or cold, sending or restraining rain, snow and hail; they can be influenced by the shamans. Rituals are performed to avert drought and excessive rain. There is a general belief that early in history, fire took refuge in a stone or a tree. Men got fire from various animals: owl, monkey, crow, bat and others. Although it was known that fire28 could be disastrous, either deliberately or by accident, many tribes believed in the fire-spirit — a spirit whose body is full of fire. He lives in the sky and wherever he sees evil he comes down and destroys it. There are protection rituals of various kinds. If a house catches fire the people leave a charm in a bowl of rice-beer and throw it at the house along with earth hurriedly collected from the grave and some black dye which is used to colour their cloth. It is believed that these objects drive away the spirits who cause the fire.

Order and Disorder

Three operant ideas have emerged: (i) Man is not unique in his origin, not even in the possession of knowledge; (ii) there is no ontological difference between man, animal and spirit; and (iii) there is no distinction between the creature and the creator. From these, it may be deduced that all elements, things and beings, are an organic part of the cosmos. Every element performs the same paradigmatic act of creation, preservation and destruction. The order of the cosmos is dependent on the harmonious functioning of all elements. Tribal cultures have not only a vision of this reality — they also live up to it. The Ongees are a good example.29

Ongees and spirits live on the same island. There are good spirits and bad spirits. When bad spirits are attracted to the living Ongees, they come and take away the Ongees. This act is known as death caused by enegetebe (to be embraced and taken away). Since good spirits do not have lower jawbones, they depend on the Ongees to provide them food. During negotiation, the good spirits convince the bad ones to let the Ongees live so that they may provide a continuous supply of food which all spirits may share. Bad spirits agree to the negotiation since the good spirits provide them with maonale, which good spirits alone are capable of making or directing the Ongees in making them. This relationship between spirits and Ongees is also the basis for seasonal translocation among the Ongees. Since the spirits and the Ongees depend on the island for food, the potential encounter with spirits who can cause death makes it necessary for Ongees and spirits to be on the same island but in different parts. Ongees explain:

In each season spirits along with winds come from a particular direction. When they leave other spirits come in from a different side and it is a different season. When spirits come to the sea, then we move to the forest for hunting pigs. When spirits come to the forest we all go to the sea for hunting turtle. Spirits and Ongees both have to be on this island, sky and sea around. But the place where the spirits are feeding is the place in which Ongees should not hunt and gather. If the two are in the same place then all the Ongees will be taken away by the spirits to the sky and sea . . . by letting the spirits in a place in a season we get more plants, more animals and more children . . . . Ongees and spirits hunt and gather in the same injube (space), but in different nanchugey (place). Many nanchugey in the land, sea and sky make one big injube in which we along with animals, plants and spirits live.

The medium of interaction between the Ongees and the spirit world is the smell (kept in the ancestral bone, which the Ongees wear as an ornament). It is the smell30 that keeps the Ongees on the island and the spirits in the sky and the sea.

The Ongees’ awareness of the cosmic order is consistent with the cosmogonic myths of the Arunachal tribes.

To conclude, every element has a form, a location, a function, and a dependent relation with other elements. Water is the first element, from which all elements originate and to which all return. The earth and sky form a universal principle of creation, both concrete and abstract, expressed by such kinship terms as husband and wife, or by such conceptual terms as used in Hindu and Chinese traditions — mithun and yin-yang, respectively. Wind and fire are brothers; and fire and water are enemies. Together they perform the function of creation and dissolution. In such a configuration of elements, the dissolution of the earth, sky, wind and fire into water is not to be considered as disorder. For, water is the first principle of cosmic order. The forces of nature are set into a mutually creative harmony. There is no intrinsic disorder in nature. Hence the oral cultures in their wisdom have made a final reconciliation with nature.

Notes

1. Cf. Saraswati (1987).

2. The tribal cosmogonic myths discussed in this paper are based on Elwin (1968).

3. Sherdukpen, cf. Elwin, op.cit.

4. Hrusso-Aka, cf. Elwin.

5. Singpho, cf. Elwin.

6. Minyong, cf. Elwin.

7. Hill Miri, cf. Elwin.

8. Apa Tani, cf. Elwin.

9. See, the famous Purusa Sukta in the Rigveda.

10. Personal communication from Ms Meng Si-hui of Palace Museum, Beijing.

11. Bugun-Khowa, cf. Elwin.

12. Dhammai, cf. Elwin.

13. Nocte, cf. Elwin.

14. Hill Miri, cf. Elwin.

15. Moklems, cf. Elwin.

16. Khampti, cf. Elwin.

17. Singpho, cf. Elwin.

18. Mishmi, cf. Elwin.

19. Singpho, cf. Elwin.

20. Idu Mishmi, cf. Elwin.

21. Wancho, cf. Elwin.

22. Cf. Saraswati (1991a).

23. Ibid.

24. Cf. Saraswati (1991b).

25. Adi, cf. Elwin.

26. Cf. Elwin.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Cf. Pandya (1991).

30. Ongees describe how smell affects the form of life: "Smell is like the water of the sea and the tides. Nobody knows or affects the water coming to land and rising and then going back. It happens always. Smell also like the tide water comes and goes from all that is living, but just like the tides change the land at the coast, the loss of smell changes the form that is living. If the smell is not kept, there is no life, if the tides’ water does not go back to the sea then there is no land and no sea." (Pandya 1991: 92).

References

Elwin, Verrier, 1968. Myths of the North-East Frontier of India. Shillong, North-East Frontier Agency.

Pandya, Vishvajit, 1991. "Tribal Cosmology: Displacing and Replacing Process in Andamanese Places", In Tribal Thought and Culture: Essays in Honour of Shri Surajit Chandra Sinha, Baidyanath Saraswati (ed.). New Delhi, Concept Publishing Company.

Saraswati, Baidyanath, 1987. "Man and Culture: the Exegesis of Science and Scripture", In Sramana Vidya: Studies in Buddhism — Jagannath Upadhyaya Commemoration Volume, N.H. Samtani (ed.), Sarnath-Varanasi, Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies.

————, 1991a. "Tribal Cosmogony: Primal Vision of Man and Cosmos", In Tribal Thought and Culture: Essays in Honour of Shri Surajit Chandra Sinha, Baidyanath Saraswati (ed.). New Delhi, Concept Publishing Company.

————, 1991b. "Rtual space : Tribal Non-Tribal Context", In Concept of Space: Ancient and Modern, Kapila Vatsyayan (ed.). New Delhi, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Abhinav Publications.