Universalism

The term universalism as it pertains to religion refers to two concepts – either

(1) the idea that a religion is meant for all humanity rather than just a certain race, tribe, caste or gender, or

(2) the belief that everyone can be saved or can realize the goal of the religion, not just the members of that religion. The opposite of universalism is particularism.

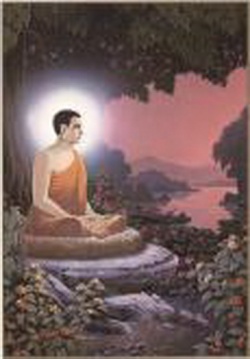

In this first sense, Buddhism is the oldest universalist religion. The Buddha is described as ‘a teacher of gods and humans’ (satthā devamanussānaṃ) i.e. of all beings capable of reasoning and comprehending. Once he said that even the trees would embrace the Dhamma if they had the ability to comprehend, ‘how much more so human beings?’ (A.II,193). After he made his first disciples, he instructed them to proclaim the Dhamma for ‘the good of the many for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world’ (Vin.I,20). The Buddha’s universalism is particularly striking when one considers that the Brahmanism of the time was so strongly particularist. Hindu scriptures and law books insist that low caste and outcaste people and foreigners (mleccha) are forbidden to read the scriptures, participate in sacred rites or even enter temples.

In the second sense that the term universalism is used, Buddhism was also the first and still one of the very few universalist religions. The Buddha once said: ‘There is no true ascetic outside.’ (samaṇo natthi bāhire, Dhp.254). This has sometimes been interpreted to mean that outside (bāhira) Buddhism no one can attain enlightenment. However, all it actually says is that, other than the Buddha’s ordained disciples, no other monks or nuns qualified to be genuine ascetics, which may well have been the case at the time the Buddha said it. Someone once asked the Buddha if any of the monks and priests of other sects or religions had attained enlightenment (Sn.1081). He replied: ‘I do not say that all monks and priests are shrouded in birth and death (i.e. saṃsāra). Whoever does not cling to sense experience or morality and rules, has given up doubts, is free from a craving and defilements, I say that one has attained Nirvāṇa.’ (Sn.1082). Thus the Buddha’s answer was not a sweeping assertion that only within his Dhamma can someone attain final liberation, but rather an ‘it depends.’ On another occasion someone asked the Buddha if he denied that those of other religions could become arahats, i.e. attain enlightenment. He replied: ‘I do not deny that others can become arahats.’ (Na kho ... arahattassa maccharāyāmi, D.III,7).

The attainment of enlightenment is not dependent on winning the approval of a deity, but by realizing certain natural truths, which everyone has the capacity to do. This being the case, it is conceivable that even those who have never even heard the Dhamma could become enlightened. However, we could say this. Openness to the Buddha’s teaching makes an appreciation of it more likely. Appreciation of the Buddha’s teaching would make the desire to practise it more possible. Practicing the Buddha’s teaching would make attaining enlightenment many times more probable.