Shamanism in Mongolia and Tibet

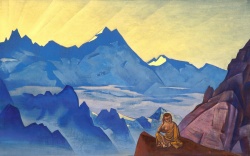

Note: As far back as the historical record goes, shamanism was the oldest religion practiced in Asia, which was once a single cultural area extending over Russia, China, India, Mongolia, Tibet, Nepal and Persia; where shamanism was concerned, these were a unified culture. From this original shamanism comes Siberian shamanism (suppressed by the Soviets, but now making a comeback in the Buryat republic), the Bon religion, and probably Chinese ancestor-worship (?). Buddhism spread throughout central Asia after 600 BC; Tibet converted from Bon to Buddhism about 800 AD; Tibetan Buddhism - usually called lamastic Buddhism - embraced most of the elements of Bon and also of Indian tantrism . . . becoming, essentially, a shamanistic religion. Tibetan lamas fall into trances, predict the future, and in many important ways behave exactly like shamans. After 1300 AD, the Mongols converted from shamanism to lamastic Buddhism, and this faith spread all the way up into Siberia.

There are important elements to this Asian shamanism which do not appear in accounts from north and south America. Although Asian shamans are no slouches when it comes to falling into trances, flying away on 'spirit journeys' and so forth, there are elements to their religion which are much more concrete than this, less sensational and (to me, anyway!) far more fascinating. Please look at the section on Tibet and Nepal, which contains descriptions of actual films of shamans undergoing trances. No withdrawing into 'shaking tents' or symbolic dream experiences for these people, folks.

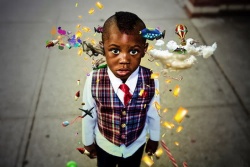

This seems to be an actual physical process that these shamans and lamas are going through - like hypnotism, something with definite triggers and symptoms. It has elements which can be studied and described, as hypnotic states can be studied and understood. For example: Tibetans raised around lamas are able to spot potential shamans; these young shamans begin spontaneously to fall into trances, after which they are taken to teachers; researchers found that the Tibetans were perfectly able to distinguish between shamanism and (for example) epilepsy or other illnesses.

In Mongolia:

boge: shaman

niduyam, iduyam: shamaness

tngri: heavenly beings

bogele: to shamanize

ujmerleku: to see something, to divine, to prophesy.

Before 1900 there were 243 incarnate lamas in Mongolian territory. But the old religion of Mongolia is shamanism, the worship without scripture, the faith which had no books; the hallmarks of the shaman were ecstatic trembling, involuntary speaking and singing. Along with the shaman's role in life, though, there were the hallmarks of what seem to be basic Bon beliefs: the cult of the eternal blue sky, the veneration of fire, the invocation of Geser Khan and ancestor-worship; incense offerings to the tngri, prayers to hills and mountains and the lha therein, and blessings and curses; and Ongghot worship.

Early shamans: wore white dresses and rode white horses. In the spring, the offerings to the ancestors were performed by women or else in the presence of women.

Description of a shaman's garb and gear: shaman costumes are inherited from previous shamans and represent a traditional garb, like a uniform.

For Mongol shamans, metal hung about their persons was essential, and some of them wore up to forty pounds of it; they wore a kaftan which closed up the back (not the sides, as is normal for an ordinary Mongol kaftan) ornamented with small pieces of metal and bells, each of which is trimmed with little strips (of cloth or leather) in snake form - which may represent a bird's feathers, ie spirit flight. The name of this formal shaman's dress is quyay, "armor" or else eriyen debel, "spotted dress".

Over this is worn an apron of tapering strips about 32 inches long, hanging down from a band 8 inches wide; the color and number of the strips varies. (Examples: one apron had nine black cotton strips; another twenty-one strips in the colors of the rainbow; another was arranged like a tiger's skin, and this last was called kurun eryen bars, "brown-spotted tiger".) Usual in Solon, Manchu and Chinese shamanism.

All shamans (even those who have abandoned the rest of their ceremonial dress) wear a further apron, which is a belt of leather hung with mirrors. Altaic shamans wear nine mirrors. The mirrors are called toli and this apron has several names: the "blue cloud-bee" and also boge-yin kulug the "mount of the shaman".

Prayer to the shaman's mirror: "O my mirror, offered by my mother-sister, red and decorated with dragons, O oppressor of infant demons." Mirrors frightened evil spirits away. Old coffin-statues and wall-paintings in Chinese tombs (Liao period, at Luan-feng) show men holding up mirrors faced outward, to frighten evil spirits away from the tombs of the dead. Further, the shaman's mirror reflects everything, inside and out - including the most secret thoughts. One shaman was quoted as saying that in his mirror, his spirit horse lives and will come when he calls. The mirror's final task is to turn away the invisible attack of evil powers, protecting the shaman. The style of a modern shaman's mirror is apparently very old (and the ideas of its powers, probably likewise) - the mirrors are in the style of old Han-dynasty Chinese bronze mirrors, which in the last centuries BC and the first AD were traded all over central Asia. They are smooth on one side, perhaps polished to brilliance, and the reverse side is ornamented with flower-tendrils, birds and figures.

Helmets etc: Buryat shamans wear red headclothes, but used to wear masks. Mongol shamans sometimes wear helmets with horns. East Mongolian shamans wear silk headclothes, usually red.

Drum and drumstick: the spirit drum in eastern Siberian cultures is a round drum with a crossways stick. The second form of drum has a handle with rattles inside it. Form of drums: on a round or oval iron ring, a thin goatskin is stretched when wet; the lower part of the skin has a hole through which a 7 inch handle is fitted; this is iron and runs in a ring of twisted bar-iron (?); the handle is wrapped with leather strips. Nine small iron rings slide along the ring of the handle, making a rattling sound. These drums are usually called "peace-drums" or "drums that welcome the New Year". The sound frightens evil demons and drives them away.

The drumstick is called the shaman's sceptre. There are two forms. One: a stick, one end of which terminates in a horse's head, the other in a hoof; the middle may be slightly curved to represent a saddle, sometimes with tiny stirrups attached. The function of this staff is to serve as a shaman's flying horse, bearing him on his spirit journey to the realm where evil demons are battled. (Ie it is a witch's broom!)

The second form of the drumstick is a thin rod covered with a snake's skin, with long colored ribbons hanging from the snake's mouth - when the drum is beaten, the fluttering of the ribbons brings to mind the darting of a snake's tongue, the darting movements of a snake. This is called the "speckled scaly snake".

Kitan shamans also sewed arrows onto their costumes and sought to frighten demons away with the noise of their cries, the sound of bells and the noise of sewn-on arrows <ie clattering together?>.

Pole-offering: made in a special offering-place by suspending meat or horses from poles.

Day of the Red Disc: a great feast, summer solstice on the sixteenth day of the first month of summer.

Earliest known Mongol beliefs: the holy numbers: three, six and nine. War drums with drum skins made from the skins of black bulls. Fire purified. The Mongols in the twelfth century made idols of their household gods (ie the Ongghot) out of felt, setting them up on the sides of the tent-doors and offering them first milk of the flocks.

A Buryat chronicle says: "The souls of shamans and shamanesses who have died before and also the souls of other dead people become Ongghot. They call forth illness and death on the living. The souls of other dead people however become demons <cidkur> which bring evil to the living." Shamans command the ancestor spirits of the Ongghot, and they fight the following evil influences:

1. Cidkun: demons, devils or demonic possession.

2. Tuidker: possession or misfortune.

3. Ada: demons which soar in the sky and which surprise men, spread illnesses and bring misfortune

4. Eliye: bird-like demons who announce and also bring misfortune.

5. Albin: wandering lights.

6. Kolcin: ghosts of repellent, terrifying appearance.

7. The teyirang-demons.

Dharani: magical formulae taught to the Mongols by lama missionaries.

Red-cap lamas (sent into Mongolia to replace the shamans) who cultivated meditation had to spend 404 days in isolation and prayer, in four terms of 101 days: the first under a solitary tree on the edge of a steppe or desert; the second in meditation at a spring; the third upon a mountainside; and the fourth and last (and most taxing) in solemn prayer, fasting and trance on a place where corpses were exposed; during this last period the lama is forbidden to defend himself in any way against anything, whether hallucination or mundane attack. And during this period he had also to fashion ritual implements: a rosary of human bone, a trumpet from a young girl's tibia and an eating-bowl from a human skull, and also a double drum (Sanscrit damaru) from two skull-caps with skin stretched over them. After this, the lama was known as a diyanci lama, a magician and hermit. An even more enlightened lama called a gurtum lama would have the ability to drive himself into an ecstatic trance, wherein he could exorcize demons and prophesy the future. (The state oracle at Lhasa was clearly one such.)

A shaman in ecstacy could do feats of strength and endurance impossible for normal men.

Mongol folk religion: prayers to "the power of Eternal Heaven", prayers to the White Old Man (Cayan Ebugen) to the three gods in the form of armored men on horseback (Sulde Tngri, Dayicin Tngri and Gesar Khan) and to the constellation of the Great Bear (Doluyan Ebugen). Offerings of incense. Worship of fire. Worship of Mother Earth, and of the four great mountains.

Peoples in central and northern Asia burn juniper branches and berries as incense.

Incense offering (Mongol sang or ubsang, Tibetan bsangs) of juniper branches (arca) and berries; also of actual incense (kuji). Incense is offered to the wind-horse flag.

Fire-prayer (ocig): recited at sacrificial offerings (takilya) at which offerings such as the breast-bone of a sheep, covered with colored ribbons and melted butter, are burned. In north Mongolia the fire-offering is celebrated exclusively by women on the twenty-ninth day or the last month of the year.

Ceremony of invitation (dalalya) gods are named, requests made to them; the gods invoked are shown the direction of their worshipers through an arrow to whose shaft are attached gold, pearls, pieces of silver, silk strips and grain; those present accompany the rite with the cry of qurui, qurui.

Mongol divinities:

Ongghot, Ongghon: ancestor spirits represented by dolls or small paintings or images.

Bogeleku: to invite the Ongghot to take possession of one's body

Sa bdag: Lords of the Earth

Koke tngri, mongke tngri: the blue or eternal heaven, which was the summit of the divine.

Tngre Ecige: the Heavenly Father

Sulde: genius angels or guardians, the militant spirits animating the standards (and the flags, which are called wind-horses) and military insignia.

Ataya Tngri: one of the oldest shamanist deities, thought identical with the all-ruling Eternal Sky.

Emegelji Eji: the very old grandmother, female version and wife (?) of Ataya Tngri.

In the southwest resides the White Lightning Tngri, riding on a white horse, along with his companions the 77 siqar, the 99 Rumblers or kukur, and the 13 terrible thunder tngri.

Invocation:

My prince Gujir Tngri

You who eat burning fire

You who have a fiery serpent for your staff

A rage-maddened wolf for your mount

Human flesh as food

Bronze and stone for heart

You who slink up like the crouching wolf

You who tear like the grasping wolf . . .

The Fire Tngri; Fire King Miraga (or Miranca); the Fire-Mother Odqan Talaqan; Tngri of the Hearth-Circle; Mighty Tngri of the Fireplace: "red in color, with one face, two hands, riding upon a brown billy-goat. In his right hand he holds a counting-cord and red silk strips, in his left hand a fire-pan. His body is decorated with various silk strips. Surrounded by numerous companions, the Tngri of Fire comes, summoned from the direction of the southern firmament ..."

The Fire-Mother may be the oldest version of the god of fire ...? She is the butter-faced one, who later becomes the white mother with the thunderbolt. In older prayers, the Fire-Mother is not one woman but the mothers Tala Khan, the older and younger sisters. These Fire-Maidens may number up to five sisters, wild deities with blinding white faces, upraised arms, wide-opened mouths with bared teeth. Four Fire-Maiden Tngri of the cardinal points are also spoken of: the eastern being white, the southern reddish-yellow, the western dark-red and the northern black.

Prayers to the Fire Mother included requests for blessings to the umbilical cord and the womb; the birth of sons; long life, fame, riches, power; for good fortune and also protection of many kinds. To protect from cattle-plague, from slippery ice, from thieves and wolves and also the ada and jedker demons, etc etc. For sur sunesun, good fortune: for "the sur sunesun of the horses, of the camels with shaggy manes, of the thick-limbed bulls, of the long-tailed stallions, of the mares with big teats, of the geldings with big swellings on their knee-joints and of the cows with big teats ... of the loud-barking dogs ..."

To the Fire Tngri were offered yellow butter, melted butter and the breast-bone of a white sheep with a yellow-spotted head, the thin layer of fat on the inside skin of a slaughtered beast; the offering of a breast-bone was covered with colored silk strips.

"Odqan Talaqan Mother arose

When Khangai Khan was still a hill

When the elm-tree was still a sapling

When the falcon was a fledgeling

When the brown goat was a kid ...

When Mount Burqantu was still a hill

When the willow was still a sapling

When the lark was still a fledgling ..."

Arsi Tngri: the Hermit Tngri

The White Old Man - called by the Mongols Tsaghan Ebugen; by the Tibetans sGam po dkar po; in China, Muan-llu-ddu-ndzi and Hwa-shang and Ho-shang; by the Japanese Jurojin; possibly the European St Nicholas. A cunning old man with white clothes and white hair, who leans on a dragon-headed staff. He is the lord of the mountain, a pre-Buddhist culture-hero who rules the earth and the waters. The white garb is probably a shaman's robe; with a blow of his staff, the White Old Man can sicken or kill cattle.

Sulde Tngri: a sulde is a genius, a protecting companion; a sulde is a standard or banner (or an ark?).

To invoke the sulde-genius against insult, calumny and deception: go to the summit of a high mountain and there offers a triangular, black offering-pyramid of gold and silver filings, spirts, milk, flour and butter, and offer a libation of black tea with a many-pointed arrow.

To invoke the sulde-genius against war, enemies, thieves and brigands: mix in spirits equal parts of the following: blood of a murdered man, shavings from iron used to kill a man - and offer this with flour, butter, milk and black tea - and further prepare a triangular red offering-pyramid and a triangular black offering-pyramid.

Description of Sulde Tngri: a white-coloured tngri, his head adorned with a thunder-helmet, his armor made of jewels, made of gold. Clothed with marvellous moon-boots, with quiver of tiger-skin filled with sharp arrows slung over the right side; with bow-holder of panther-skin filled with the dreadful bow, hung over the left side of his body; with a sharp sword girt about the hips; holding in his hand a three-pointed bamboo staff. Mounted on a horse, with on his fingers an iron falcon flapping its wings upward; leading a white lioness on the right, a great tiger upon the left ...

Elsewhere the sulde are described as nine brothers riding fiery horses, with falcons flying above them, with lions rearing by their left shoulders and tigers springing by their right shoulders.

Dalyisun Tngri: called the high prince of the enemy gods or dGra lha (every man having a good god and an enemy god to protect him, and when a shaman lures away these good and enemy spirits, the man is in grave danger of occult attack): a rider with magic powers, on a horse as if riding upon white clouds, holding in his right hand the lance which takes enemies' lives, in his left hand the blade which reaches the evildoers, ornamented with fluttering ribbons and jewels.

Gesar Khan: the third rider tngri: protector of warriors and herds, especially herds of horses. Described as having a reddish-brown face, golden-yellow hair - his right hand holding arrows with the sign of Garuda, in his left hand the bow with the tiger's sign. A sun-like helmet on his head, a moon-like shield hangs on his shoulder, a star-like coat of mail covers his body. The fine sword of understanding upraised, riding on the horse of wisdom. With arrows like lightning and shooting-stars. With the King of Birds, Garuda, fixed on his helmet. Etc etc.

In Tibetan epics, Gesar Khan also wields the sword of understanding and wears the moon and sun and stars. He fought and killed the Siraighol Kings. He killed the twelve-headed giant. His beautiful wife is named Roy mo. His vanguard are thirty-five heroes and 360 warriors.

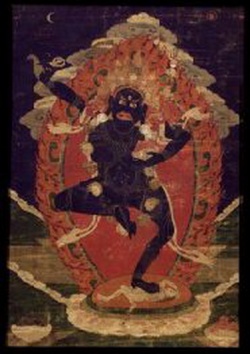

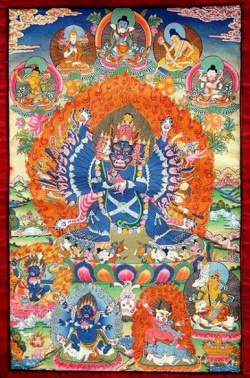

In India:

Indian mystics (yogis, ie Red-cap monks) are initiated by Tantric goddesses called Dakinis, many of whom haunted burial places. Description: "rays of light like sunshine came from the eyes of some, others rode on buffaloes with a noise of thunder, others held knives, stared with eyes like grains, held piles of skulls, rode on tigers, carried human corpses, rode on the backs of lions, ate entrails and rode on the backs of garuda birds, some with fiery lances rode on jackals, several with five heads conjured up a sea of blood, some had innumerable hands and carried many different kinds of creatures, some of them held their own decapitated heads in their hands, others held their torn-out hearts in their hands ..." The author refers to these Tantric yogis as "Buddhist Magi" who conquered the old Bon gods in the Tibetan mountains and bound them by oaths to guard Buddhist treasures - ie holy writings.

Rite of the rising corpse (ro-langs) an act of Tantric magic from India. David-Neel wrote in Heilige und Hexer: "The magician is locked in a dark room with the corpse. In order to raise the dead the magician must lie on the corpse mouth to mouth, constantly repeating the same magic formula, without ever once allowing his thoughts to stray. After a few moments the corpse moves, rises up and attempts to flee. The magician must then hold him very tight in his arms. The dead man struggles more and more violently, and whilst he follows these movements the magician must not take his mouth from the mouth of the corpse. Ultimately the tongue of the corpse hangs out, and this is the decisive moment. The magician must seize it and tear it out, and when this is done the corpse falls back motionless once again. The magician now carefully dries and preserves the tongue of the corpse and it becomes a powerful magic weapon." If the magician fails in this rite, the demon-possessed corpse slaughters him then and there.

Ceremony of gCod, the "cutting off" of human egotism. A mystic drama with only one actor, performed in a wild and out-of-the-way spot or perhaps a place of internment. The mystic must have a small double drum or damaru, a horn made from a human skull or rkang-gling, a bell, and a symbolic tent. First thing in the morning the adept celebrates the white sacrificial repast; in the day the mixed, in the evening the black, and during the night the terrible red repast. While he is engaged in the black repast he gathers up all the bad Karma in the entire world; during the red repast he offers up his own body to demons, as compensation for his sins and selfishness in this and former lives. As with the awakening of a mandala or magic circle, a goddess of his imagination then rises from his head and cuts it off. The adept then imagines the cutting apart of his body in sacrifice, chanting all the while a spell which includes: "I give my body to the hungry, my blood to the thirsty, my skin to the naked, and my bones as fuel to those who suffer cold. I give my good fortune to the unlucky, and may the breath of my life restore the dying. Shame on me if I draw back from this sacrifice! Shame on all who hesitate to accept it!" The adept is supposed to repeat this ceremony over and over - some overimaginative chelas are said to have lost their reason doing so - until he recognizes that the demons and gods he conjures are of his own soul, partaking of his eternal spirit. (Or some such thing.)

A derisive Tibetan Queen speaking of the Tantric rites:

What is called Kapala is a human head laid on a stand;

What is called Basuta is entrails spread out;

What is called bone trumpets is made of human leg bones;

What is called the Holy Spot of the Great Field is human skin spread out;

What is called Rakti is blood scattered on sacrificial pyramids (bali);

What is called Mandala consists of iridescent colors;

What are called dancers are people carrying wreaths of bones!

This is not religion; it is the evil that comes from India to Tibet!

In Tibet and Nepal:

human flesh offered to the lha: called the "great meat" in tantric terminology

yul lha of Northeastern Tibet may be offered a libation of kumiss.

The drink of immortality - bdud rtsi, Sanscrit amrta - offered to the deities.

For certain Bon rites the offering must be the blood of a mi rgod. This means, verbatim, "wild man" - the so-called snowman of the Himalayas, known to Tibetans as Gongs mi (glacier man) or Mi shom po (strong man) and Mi chen po (great man); the Lepchas call him Chu mung (snow goblin) or Hlo mung (mountain goblin) and worship him as the god of the hunt and master of all mountain-game. The Tibetans and Lepchas describe him as a huge dark-brown monkey with an egg-shaped head scantily covered with reddish hair, about 7 ft tall when standing; he lives in the highest tracts of the mountain forests, but goes out sometimes to eat a salty kind of moss growing on rocks on the morain fields; at these times he may leave tracks crossing snowfields. Similar traces are supposed to be made by a bear, known to the Tibetans as Mi dred; this is the expression "mete" found in the reports of Himalayan expeditions and wrongly translated "abominable".

Used for magic: human skulls to make skull cups and drums; human thighbones to make bone trumpets. Bone-aprons, bracelets, etc, are worn by Tibetan tantrics while performing rites.

Damaru, magic drums. Small drum, shaped like a sand-glass. Larger drum, made from the tops of two human skulls joined together, with human skin stretched over; the handle is a piece of leather or strong cloth fastened to the ring joining the halves of the drum, and from this ring also issues two strings, each with a leather knob or wooden bead at the end. When the drum is swung, the strings fly up and the beads strike the face of the drum, making a rattling sound. The skulls of children who die accidentally in their eighth year are especially powerful. Bon tambourine: about twenty inches in diameter, with a short wooden handle; over the frame is stretched an antelope's skin, held in place by strings drawn cross-wise over the frame. When played, it is held in the left hand close to the sorcerer's face, the skin side facing downward; the right hand brings a curved wooden stick straight up to strike the leather. Bon bell: flat bell made of metal, rung with the opening turned upward; often a red or white yak-tail is tied to it.

The flesh of an eight-year-old child should be used in magic rites.

Mdos, thread-cross: threads or cords of many colors strung on arrangements of sticks. Can be very large and elaborate and mounted on the roofs of lamaseries; after a certain period of time has passed, the thread-cross has caught enough evil that it has to be taken apart and ceremonially burned. Thread-crosses are found in Tibet and also Mongolia, South Africa, Peru, Australia, Sweden. Tibetan thread-crosses predate Buddhism. Evil spirits are supposed to get entangled in the mdos like flies in a cob-web; thus, houses are protected by mdos hung above the doors and on the roofs, and in Ladakh the monasteries and their locales are protected by very large thread-crosses.

Ancient Persian oracles were supposed to cast themselves into shamanistic trances by drinking hashish.

Tibetan oracles fall into shamanistic trances, and in these trances often bend swords or even twist them into spirals; such a sword is called rdo rje mdud pa, knotted thunderbolt; it is highly priced, a valuable talisman against evil spirits, and is kept wrapped in white scarfs and fastened above the house door for protection. Knotted ribbons are also given away by oracles in trances, and these amulets guard against sickness. Sick people are brought into the presence of a possessed oracle, who will beat them with his sword to drive the evil out of them.

Minor oracles may thrust their own swords so deep into their chests that the point emerges at the back, and withdraw it without suffering harm. An oracle-priest divining with his sword: while in trance, he stood and hurled his sword right out of the room, through an open door into the courtyard where a number of signs had been drawn on the ground; the sign by which the sword fell indicated the future. People often get killed by oracles flinging their swords (a crowd always attends an oracular trance) and oracles frequently attack or even kill spectators while in ecstatic trances. In these cases it is assumed that these were evil people, and the spirit which possessed the oracle was punishing them for some sin.

Scapulimancy: divination by shoulder-blade, practiced in Tibet, Central Asia and North America among nomadic peoples. A sheep's shoulder-blade is stripped of meat is laid in the fire; the resulting cracks in the bone give the answers to questions. This practice predates Buddhism and was used by Bon sorcerers in ancient times; in special cases the Bon magician will divine with a human shoulder-blade rather than that of a sheep. Divination by the voices of birds, especially ravens, is also very ancient.

Ge sar oracles: Three methods of divination were supposed to be invented by the mythical king Ge sar: a method called mda'mo in which a number of arrows, each bearing a number, are put in a high vessel which is then shaken until one or several arrows jump out. The numbers correspond to entries in a book of divination. This is called the Ge Sar mda'mo.

In the second method, called the Ge sar rgyal po('i) pra mo, a shrine with an image of Ge sar is set up. The king is a white figure wearing a cuirass and helmet of crystal, a white cloak, high leather boots; bow-case and quiver and sword hang from his girdle; he carries a stick of cane and a battle-lance with a white pennant. Among bowls, wheat grains, butter lamps etc etc on the table, a mirror is laid down and covered with silk of several colors (but never black) and a yogi sits in front of this table and intones prayers to Ge sar. A boy about eight years old is now brought in and sits in front of the mirror, which is uncovered so that the boy can gaze into it and describe what he sees, answering questions as he does. If after three attempts the boy sees only his own reflection in the mirror, then Ge sar has not come to answer the prayers. A sword-blade may also be used as the mirror.

Bya drug mo: the six-bird divination - also introduced by Ge sar. No details are known.

Casting a curse: take some nail-clippings or such from the victim, or at least the earth from his footprints. Draw circle on paper, divide by two lines in X; draw image representing victim bound by heavy chains. Write on paper these lines The life be cut ... The heart be cut ... The body be cut ... The power be cut ... The descent be cut. The paper and clippings plus black-magic objects are put in a yak horn along with one or two live black spiders; the horn is sealed with a stopper made from the hair of a corpse, wrapped round with black thread tied crosswise, and with several nails from a poisonous wood are inserted under the threads. Throughout, the sorcerer never touches these materials with his bare skin. When he is done, he must enter the victim's house unseen and bury the horn in the foundations.

Shamans often have magic swords (much like Tibetan oracle-priests) which are supposed to be presented to them at the time of initiation. Prospective shamans suffer the "shaman illness", often at puberty or during the teenage years; they remain sick until an elder shaman begins to teach them. Newly-chosen Tibetan mediums suffer from fits, and must be found and initiated in much the same way. There are characteristic symptoms of the shaman illness and of divinatory trances. Before becoming a shaman, the novice stricken by the "shaman illness" experiences his death and subsequent rebirth - as in the gcod rite, he sees himself being cut up and the flesh boiled in a cauldron, ie fed to demons and gods.

When a Tibetan manifests mediumistic powers, he usually begins to fall into spontaneous trances at about the time of puberty. This is not epilepsy, and the Tibetans are able to distinguish clearly between epileptic fits and oracular trances.

Description of trance of the Nechung chos rje or master oracle, taken from a color film shot by the Tibetan authorities. The medium, dressed in ceremonial robes but bare-headed, is led into a chapel and settled upon a throne. He sits in a characteristic position, with legs set far apart and feet turned out, both hands on his knees. While prayers and songs resound around him, he gradually becomes restless. His eyes shut, his face turns red, his feet and body begun to shake spasmodically; during this time he experiences a feeling of great heat. Incense is blown into his face. His heavy helmet is lowered onto his head by assistants, who stand by him holding the helmet up. Priests blow thighbone trumpets right into his ears. His convulsions grow. His breathing puffs and snorts, his face turns dark red and begins to swell up. When this stage of the trance arrives, the attendants release the helmet and tie it onto his head; this is the clear moment during which he has been possessed by Pe har, the great spirit. Despite the weight of the helmet, the medium rises and bows.

Attendants bring him objects, which he may brandish and then drop: he shakes a lance, tosses seeds at the audience, pours beer or tea or milk into the hands of spectators. He dances, and speaks in gibberish (notes are taken by the priests) and then collapses suddenly and is carried away in a state of unconsciousness.

Second description: oracle rests on throne, supported by assistants, eyes shut. Prayers are said. His eyes suddenly open so wide that it appears they will pop out of their sockets. He falls into a fit: his face reddens, he sweats and gasps for air; his features contort, he tries to jump up, waves his hands wildly.

His eyes shut again, his mouth half opens. His face is yellowish. Spasms shake his body, his lips are covered with froth, his head seems to swell up. Attendants lower the helmet and tie it on. He stands and executes a slow dance; then pauses, dances wildly while his face again turns red.

They question him. His face appears sad, the skin drawn and cheek-bones and chin sticking out sharply. He begins a wild grotesque dance. He throws seeds at the onlookers, collapses while trembling ecstatically. His eyes open, the white rolling up.

Third eyewitness description: a young medium sits on an improvised throne, in the characteristic position. White incense smoke is blown into his face in a thick fog. He begins to quiver and tremble and shake; the muscles of his face twitch, he bites his lips as if in pain and stirs uneasily. His feet and knees start to shake. Once he slumps forward and rests his head on one hand. He wipes at his face which is covered with sweat, his breathing becomes heavier and he begins to puff out air with a deep gurgling sound. Attendants chant throughout. He swings the upper part of his body with a rhythmic rotation characteristic to the oracular trance. His face becomes dark-red, the lips blue and covered with froth, the features swollen. He gurgles and puffs, suffers convulsions.

Suddenly he leaps several feet high from a sitting position. He beat the shield on his chest with one hand, the knuckles becoming covered with blood; he appears to feel no pain. The gurgling grows louder and he tries to grasp his throat with both hands; attendants stop him.

Presently the puffing, though loud, becomes more rhythmical and the movement of the medium become smoother. His face distorts into a fierce expression. He gulps a few mouthfuls of cold tea. A short sword is handed to him; he grasps the hilt with his right hand, sets the point against the wide leather belt he wears around his waist, he presses the sword into a U-shape. "After the end of the ceremony I tried to bend the sword straight again, but without the slightest effect. On another occasion the same oracle twisted a sword with his bare hands into a spiral."

The oracle answered questions, then suffered several strong convulsions and became quiet. About two minutes later he opened his eyes and looked around, once more quiet. He drank some tea and sat bent over for about five minutes; then went into trance again. During this trance he suddenly, with no warning, jumped back and cracked his head against the wall, losing consciousness and cutting his scalp; his helmet (it had a thick lining) preventing further injury.

Upon waking he rests again, and then enters a third trance. His robes are now completely soaked with sweat. After this trance, he rests for some three hours and then departs -still very weak, supported by attendants.

Some oracles, when suffering from exhaustion after trances, rub all their joints with nutmeg mixed with melted butter, to speed up their recovery.

In the Buryat Republic of the USSR:

Mongol myths (of the Buriat Mongols, in Siberia around 1900): of Esege Malan or Father Bald Head (who is the highest heaven itself) and Ehe Tazar, Mother Earth. Stories of Gesir Bogdo, Ashir Bogdo, and The Iron Hero.

Ongons or gods protect the houses and property of the Buriats. Those that guard the home are hung high in one corner of the house. Those that guard the steading are in a box mounted somewhere outside, a box with a glass door, and these outside gods could not be removed from their box nor the box carried into the house, lest misfortune follow; in the box the writer examined, the gods were small drawings of men and women, and with them were a few small dried skins. Those that guard the fields are mounted on posts in the countryside; the writer says on the farm he visited, these Ongon were a collection of twenty or thirty square posts in a pasture, set up on a hilltop; each post had a board mounted atop projecting on the east side like half a roof, and beneath this, on each post, there was a hole with a sliding cover, within which was a small box with a handle and sliding cover. Each villager had one post, which he must set up as soon as he marries and has a home; when he dies, someone takes away his Ongon and without ever looking behind him, must carry it to a forest and hang it in a tree to rot. Within the box the writer was allowed to examine, there was a little bag of tobacco and several pieces of silk, one with several tiny metal images and two with tiny painted figures. When the box was put back, it was first purified by being placed in juniper-herb smoke from a tiny fire kindled on the spot, which the box's owner stamped on ritually three times, to make smoke.

In this country, and one other place in Asia, the Horse Sacrifice is still practiced, as it has been among Mongols since time immemorial. It is a great festival, the surviving shred of an ancient religion. Upon the Hill of Sacrifice, nine horses are slain; the writer saw the last two die, and described them as fine white mares. His host tried to keep him from seeing the ceremony.

Bibliography:

Walter Heissig, The Religions of Mongolia

Rene de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, Oracles and Demons of Tibet