A Buddhist View of Suffering by Peter Morrell

A Buddhist View of Suffering

by Peter Morrell

Buddhism is a religion pretty centrally concerned with suffering. It never really stops studying the suffering of oneself and that of other people. These form a central focus of the religion, its practice and its philosophy. One is encouraged to explore what suffering is, the various forms it comes in and their root causes. Though they can all be reduced to attractions and aversions based upon the illusion of a real self, which desires certain things and is averse to others, yet this is not immediately obvious or a point easily grasped:

"And the people, who hide themselves behind a wall of illusion

Never glimpse the truth, then it's far too late, when they pass away."

[George Harrison, Within you without you, 1967]

We live much of our lives in an entangling spider’s web of these desires and aversions. Buddhism aims at the demolition of the self, the creation of subtle mindfulness, bliss, great compassion and moderation and gentleness. These must be cultivated within a general atmosphere of subduing the passions, subduing the desires and aversions and of cultivating reflection and a caring attitude to all life.

The Theravada tradition primarily emphasises ethical conduct, mindfulness and self-restraint, which aim at achieving enlightenment, probably after many future lifetimes. The Mahayana tradition primarily emphasises the attainment not just of enlightenment, but also of full Buddhahood. This subtle difference means training not just to gain insights and personal release from Samsara, but also to actually become a Buddha, a fully enlightened being who compassionately helps others through their lives to attain wisdom and realisation. In the Mahayana, the emphasis is upon becoming a bodhisattva, which is a Buddha-to-be who strives for the enlightenment of others ahead of his or her own. The Tantrayana comprises Mahayana paths that aim to achieve full Buddhahood in this lifetime.

In the Mahayana Zen tradition, the rather ruthless destruction of the self through reflection, passivity and self-denial is the fruit of a life of great discipline, simplicity and focus. In this way, it aims to achieve perfection of mind control and ethics through the exhaustive realisation of emptiness and mental stillness:

"The farther one travels

The less one knows."

[George Harrison, The Inner Light, 1969]

All other aspects of human life, and even Buddhist scriptures, are deliberately reduced to a stark minimum. The meat of the Zen life is unrelenting confrontation with one’s own psychological shortcomings:

"We're just two lost souls swimming in a fish bowl, year after year,

Running over the same old ground.

What have we found?

The same old fears."

[Pink Floyd Wish you were here, 1975]

The Tibetan tradition strives for the attainment of selflessness through practising extraordinary compassion and by putting the suffering of others before one’s own to develop the very special, selfless love of a Buddha as well as his wisdom. This strives to develop these two key aspects of Buddhahood together, side-by-side. Mindfulness and meditation also play a prominent role. Ritual, visualisations, rote learning of scriptures and engaging in debates on the finer points of doctrine are also used to maximum effect arousing religious feeling and a thorough understanding of emptiness.

It is true to say that Buddhism begins and ends in the study of suffering. This lies at its root just as it lies at the root of life itself. We are born into suffering - "like a dog without a bone, into this life we’re thrown" [The Doors] – and we all must die and experience pain and loss. Obviously, we also experience great joy as well, but suffering seems to be a dominating influence of all life and in our lives. Buddhism concerns itself very much with the study of suffering in all its forms, what it is, how it arises and how its causes might be cut, overpowered or transformed into a life-plan that minimises suffering coming into being, by cutting off its causes within one’s life, attitudes and behaviour. In this way, a ‘new life’ can be forged when effort and determination are harnessed to the task. Real change and real improvement are only possible when great effort is made at the right tasks. Such are the schools and paths of Buddhism. It is thus a religion of self-transformation and self-improvement, through application of continuous effort:

"Try to realise it's all within yourself

No one else can make you change."

[Within you without you, George Harrison, 1967]

Because Buddhism is a religion primarily involved with suffering, so it especially identifies with the working classes who are burdened with ‘failure in life’ and the suffering of delay, lack of progression, frustration and poverty, etc. Buddhism therefore identifies to some degree with all poor and suffering people like that, as it makes a central study of such figures. It identifies as a subject of its own study, therefore, with the grosser forms of human suffering, which are predominantly found in the lower social strata of society. This is not to say that rich and privileged people do not experience suffering, or even those happy people who happen to be enjoying life now. They also suffer to some extent.

In any case, there are subtle and pervasive forms of suffering and impure states of mind even for rich and happy people. They also suffer losses, disappointments and frustrations. They are also burdened with jealousy, avarice, fear and desire. Yet, suffering is predominantly confined to the poor and lower classes compared with the rich. One of the defining features of working people is that they suffer more than average setbacks and disappointments in their lives. They therefore form a good subject of study for Buddhists. Their position in society gives one a justifiable sympathy towards them, and one is predisposed to empathise with their suffering, even if a strict Buddhist might contend that their suffering is the ripening of their own bad karma [is their ‘own fault’] or that it is illusory in the deeper sense of it being an aspect of a non-existent self that is a mental construct.

It can truthfully be said in Buddhism that meditation and mindfulness on their own may not achieve selflessness, because employed alone these forces do not directly counteract the ego. The ego must be tackled; it must be subdued and diminished if true realisation is to occur:

a

"When you've seen beyond yourself then you may find

Peace of mind is waiting there."

[George Harrison, Within you without you, 1967]

For example, one can engage in meditation and mindfulness for years, know all the great teachings by heart, and yet still remain innately arrogant. This is because our sense of self is so persistent and so hard to dislodge. In some of us, the self becomes too solid and we identify with this mind, this body and the details of this life too tightly. We are then very reluctant to let these elements go, to loosen their grip and let ego melt away:

"I built my prison stone by stone

how many useless knots I tied

I dug the pitfalls in my path

how many useless tears I cried."

[Robin Williamson, Cutting the Strings, 1970]

If we rely on these matters so much then our sense of self is very powerful; if, however, we loosen our sense of identification with our body, our mind and our position in life, making them slightly more distant and less important, that is being non-attached to them, then the sense of self becomes correspondingly diminished. But awareness then brightens and joy and compassion actually become possible:

"You give all your brightness away and it only makes you brighter."

[You get brighter every day, Mike Heron, 1967]

It seems one cherishes others to the degree that one no longer over-cherishes the self:

"You never enjoy the world aright

Till the sea itself floweth

In your veins and you are clothed

With the heavens and crowned with the stars."

[Thomas Traherne]

This is the correct application of non-attachment and mindfulness as spiritual antidotes of egotism. Whether through emptiness or compassion, or patience, or giving, somehow or other one must release the grip of the ego in order to achieve great realisations. There simply is no other way.

It is the resistance the ego puts up against the realisation of selflessness and emptiness that prevents us from gaining good insight. This resistance can be enormous in those who have habituated a very solid identification of their current consciousness and life situation with the bright and empty awareness that underpins all life and flows through all things:

"And to see you're really only very small

And life flows within you and without you."

[Within you without you, George Harrison, 1967]

Ego is terrified of its own extinction above all else. That which flows through all things cannot be destroyed, thus no fear need arise.

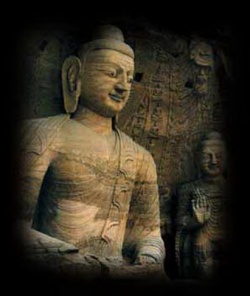

When these ideas become fully absorbed and appreciated, it then becomes possible to understand why Buddha was called the Subduer, the World Conqueror, the Tathagata, the One-Gone-Thus, the World Honoured One, the Great Sage of India, World Teacher and the One Gone to Bliss [[[Sugata]]) for truly when ego is destroyed and a joyful and compassionate selflessness has emerged, then mind has truly merged into bliss, which is Buddhahood.

Strive to be "not attached to the pleasures of mundane existence."

"craving cyclic existence thoroughly binds the embodied."

"Emphasis on the appearances of this life is reversed."

"If you think again and again

About deeds and their inevitable effects

And the sufferings of cyclic existence,"

"generation of a complete aspiration to highest enlightenment," which is the same as "the supreme altruistic intention to become enlightened."

"Have entered into the iron cage of apprehending self (inherent existence),"

"the realisation of emptiness," which is "the cause and effect of all phenomena."

from Tsong Kha pa, Three Principle Aspects of the Path