Tibetan art

Inseparable from the tenets and precepts of Buddhism is a concept of reality that has led some modern observers to consider Buddhism as much a philosophy as a religion. Since Tibetan art, historically, has been entirely and exclusively religious, to that extent it is something of a philosophic art as well. Although much Tibetan art uses figuration, depicting person-like beings and creatures that, however mythological, supramundane, or surreal, are pseudo-realistic and thus recognizable, it differs fundamentally from Western art, specifically from religous art. Western art uses illustration to depict its religious narrative; artists imagined and depicted every being in the biblical story and cosmology, including such mysterious concepts as the holy ghost (often represented through the symbol of a pair of wings, which is nonetheless a recognizable image from our world), such cosmic actors as Lucifer/Satan and the archangel Michael, and even God himself. (Judaism and Islam forbade the use of representational imagery altogether.) But Tibetan Buddhism devised an art that goes beyond illustration, conceiving figures and giving form to beings who have no inherent, intrinsic form and, according to Buddhist teaching, no tangible reality, in order to represent abstract concepts or spiritual attainments or conditions such as compassion or wisdom. Thus Tibetan art, uniquely, is an art that uses figuration and representational images to express abstraction.

Moreover, especially through its use of mandalas, Tibetan art is an integral part of a spiritual practice and process. A Christian may pray to a painted image of Jesus or Mary--an illustration of the divine being--but a Tibetan Buddhist uses the painting itself as a tool to facilitate the attainment of a spiritual state, and even to achieve transformation into the divine being that images such a spiritual condition.

The Buddha taught through dialogue, through probing questions, and reasoned explanation, rather than through dictum. He did not seek of his listeners submission through faith, but rather conviction based on understanding. His enlightenment was a truth he reached through profound understanding of reality, rather than something bestowed by divine revelation. Thus, the essence of this teaching is that one must not merely accept what is handed down by tradition or authority, but rather "see" for oneself what is true. With this emphasis on "seeing" and understanding, rather than on faith and belief, visual art assumes a central importance, in that vision along with mind are the means for such perception.

FEATURES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF TIBETAN ART

Tibetan art is fundamentally abstract, but arrives at this position from an understanding of reality that is totally contrary to traditional Western assumptions. Yet it is not expressionistic: whereas a contemporary Western artist might use visually abstract elements of shape and color in what is an essentially personal code, to convey a personal concept or feeling about life or reality, or the divine or the hereafter, the Buddhist artist does not express personal views or feelings. Instead, a code of conventionalized symbols, legible to all and to which all subscribe, conveys the common understanding. The components of this code include a variety of divine and supernatural beings in their different roles and stations, as well as the manner in which they are depicted.

The Tibetan Pantheon

The historic Buddha, Shakyamuni, made no mention of a divine creator and refused to be drawn into speculation about the subject. As to whether Shakyamuni promulgated rituals of worship, it is the position of Tibetan Buddhists that the tantras (see below), which lay out such rituals, are authoritative Buddhist works, canonically valid as the word of the Buddha. Yet Tibetan Buddhism conceives of a pantheon of gods and divine beings, bewildering in size and complexity, almost too numerous to be counted. This enormous cast of divinities and supramundane beings, of various origins, animate the walls of Buddhist gompas.

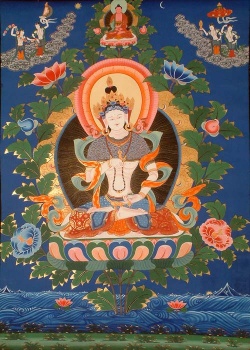

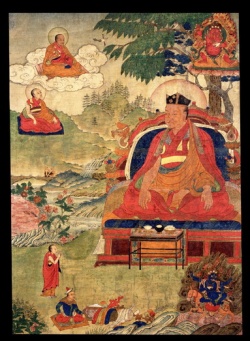

Although Tibetan art portrays human beings, including the historic Buddha Shakyamuni, as well as arhats, spiritual masters, great lamas, and founders of different religious lineages, the preponderance of its images depict supramundane beings. In their main groups, these are: Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, female deities, protectors or tutelary gods (yi-dam), defenders of the faith, guardians of the four cardinal points, and minor deities and supernatural beings. To add further complexity, the leading gods emanate in different forms and appear in various manifestations.

They are depicted in Tibetan art in precise and particular ways, and so numerous are the various deities, and so complex their representations, that the subject may appear daunting. The different manifestations add to the potential confusion, as essentially the same deity is depicted in multiple forms and even in apparently conflicting images. Yet, although only a specialist can make close identifications, the viewer can acquire a general sense of the types of beings depicted in painting or represented in sculpture, and of their nature, role, and significance in the grand cosmic panorama. There is an order--a hierarchy and a system--to this seemingly wild jumble. Therefore, before any survey of the main classifications of Tibetan deities, a few explanations may be helpful.

As they are meant to be understood at the highest level, the Buddhist deities do not exist outside ourselves, but represent aspects of innate human potential--the capacity for compassion, wisdom, mental discipline, and other spiritual conditions and achievements. Having no distinct, independent existence or objective reality, the deities are only symbols of abstract qualities, with no intrinsic worth or value in themselves; they come from one's mind and also from the universal mind. Tibetans do not imagine that they might encounter red or blue beings with four heads and eight arms. Although depicted in Tibetan art as beings in human shape, they are, rather images of spiritual states and conditions, personified.

Identifying poses, symbols, and attributes

Tibetan art uses a sort of visual alphabet or code, whose features help to identify various deities. These features include color, gesture, pose, dress, and the holding of symbolic objects. At the sight of deities who are red, blue, white, yellow, or green, the uninitiated viewer might marvel at what appears to be the artists' freedom in the use of color, but that perception would be inaccurate. Rather, the deities must be depicted according to the appearance proper to them, and with the proper features, each of these elements possessing a symbolic meaning. Thus, among the Dhyani-Buddhas (see below), Ratnasambhava is always yellow, Amoghasiddhi always green. The Manushi-Buddha wears a patched robe and no ornaments, and the great Bodhisattvas are shown in royal dress, bedecked with ornaments.

The supramundane beings seen on gompa walls were not painted there for the sole purpose of decoration, and it is not even accurate to think of them as depicted, however beautifully, as an act of adoration, or as depicted for that purpose, as a Christian artist may create images for the purpose of adoration. Rather, they are vehicles for meditation and transformation, and in creating the image, the artist accumulates merit. In viewing an image and meditating upon it, the believer seeks ultimately to draw that deity into him or herself, to be transformed into the divine being or the spiritual condition it represents, achieving union. In Christian terms, this would be considered heresy.

Symbolic gestures and poses, deriving from the Hindu tradition, are an important part of this visual code. Mudra, for example, are gestures of the hand that represent particular attitudes or actions. In the mudra known as Dharmachakra or turning the Wheel of the Law, the thumb and forefinger of both hands are closed in a circle, with the hands held near the level of the heart: this mudra is appropriate to certain deities and represents preaching. Varada, the mudra symbolizing charity or giving, is shown by a lowered arm, open palm held outward, with all the fingers extended downward, and is appropriate to Ratnasambhava. Asana are symbolic body positions or poses. A well-known example is the Dhyanasana (also known as Vajrasana or Padmasana), the meditation position in which the Buddha Shakyamuni is usually shown--seated, cross-legged, with the soles of the feet visible. There are many other poses, some appropriate to peaceful deities, and others to wrathful ones. An angry deity, for example, is often shown in Alidhasana, standing, with the left leg bent at the knee and the right leg thrust to the side.

Various deities have their appropriate type of throne (a lotus throne, a diamond throne, etc.) and their own particular vahana or mount--animal, bird, or mythic creature. And deities are also depicted holding their own appropriate ritual or symbolic objects. The vajra (dorje in Tibetan) signifies a thunderbolt. This ritual object is not represented as a jagged-edged bolt of lightning, but rather as a small, double-headed scepter, highly stylized. It later developed a parallel signification as the diamond symbol (see below). Among other ritual attributes, a book symbolizes wisdom, a lotus flower is the emblem of purity, a sword is a weapon for destroying ignorance, etc.

Of these, the vajra is the most important of all tantric symbols. It has ancient Indo-European roots--the thunderbolt was wielded by Zeus and by Thor, and similarly appears in Vedic (early Hindu) culture as the weapon of Indra, king of the gods. It also correlates to the lingam of Shiva. As scepter, thunderbolt or phallus, the vajra connotes royalty and is the image of power, the word itself recognized in the names of several deities: one of the three greatest Bodhisattvas is Vajrapani, thunderbolt-in-hand; and Vajradhara (thunderbolt-holder) and Vajrasattva (thunderbolt-being) are names for various forms of the supreme deity. The vajra gradually became linked, conceptually, to a diamond, signifying that which is pure, translucent, indestructible, and adamantine (i.e., the truth of the Buddhist doctrine). As both thunderbolt and diamond, with all their connotations, the power of the symbol is doubled.

In all Vajrayana ritual, the officiant holds a vajra, along with a bell (ghanta). In these rituals, the vajra symbolizes compassion, but it is also explained as symbolizing "means" (often referred to as "skillful means"), for compassion is the means toward achieving enlightenment, and with the dual concept of power and indestructibility inherent in the symbolic vajra object, it represents the invincible power of compassion. The bell signifies wisdom or insight (prajna): the clarity of mind that is able to identify misconceptions, illusions, and falsehood, and discern truth. In Buddhist terms, this means understanding both the impermanence and the emptiness of all things (the void), meaning that phenomena have no independent existence.

Means is the active part of the equation, its action being to remove ignorance and to make wisdom, which was innate and latent, manifest. The vajra, thus representing means, is identified as the male aspect, and the bell, representing wisdom--that which is sought--as the female aspect. (The lotus has also been identified as another emblem of the female aspect or principle, a symbol that reinforces the sexual aspect of this imagery.) Being two, the vajra and the bell represent duality, but they must be used together: wisdom is sought, but without means, is unattainable, and compassion is the means by which wisdom is attained. Enlightenment, which dispels the illusion of duality, depends on both compassion and wisdom, and is attained by the union of these two. Even the shapes of the two ritual objects, thunderbolt-scepter and bell, are symbolically representative and not coincidentally suggestive.

The Artist as Medium

Not only must a Buddha be portrayed in the proper color and dress, with the proper physical marks and appropriate mudra and pose, but must also be depicted exactly in the correct proportions that have been laid down for artists. This is done according to an iconometric diagram that shows the precise span or distance between each physical feature, as, for example, the distance between the eyes, the length of the nose, the width between the ears, etc., down to the smallest details. This is because the Buddha himself was of perfect proportions, and only by exactly reproducing those proportions can the image serve as a spiritual medium. In the process of creating a new painting of the Buddha, on either a wall or a cloth scroll (thangka), an iconometrically correct diagram is first pencilled in. When monks fashion tormas, figurines modeled from tsampa (a dough made of barley flour) and colored butter that are used in important rituals, they consult a pattern book in order to achieve exactitude. Thus there is no range here for an artist's free expression. Reproduction is the aim, not independent expression or creation. If incorrectly drawn or painted, no power attaches to the image, and no transformation can occur.

These strict rules of iconometry govern the figure of a Buddha, but in the depiction of other beings, and in the broader sense, Tibetan art is not concerned with reproduction of the everyday world, but rather with the paradox of depicting that which is not seen. The Tibetan name for the painted scrolls most commonly known as thangkas is mt'on grol, "liberation through sight." Tibetan painting, fundamentally abstract or conceptual, is meant to be used to achieve spiritual transformation. Envisioning a spiritual state, it is thus not concerned with pictorial realism and with such devices as perspective and shading, giving the illusion of volume. To further dispel such illusions of naturalism, the deities are depicted in a plane of uniform light, with no identifiable, external source. The reality portrayed is, instead, transcendental, ultimate.

TANTRIC IMAGES

Peaceful and Wrathful Forms

The image of Buddha (Shakyamuni) known around the world is that of a seated figure in serene meditation--an icon recognized by people who know little else about Buddhism. Yet Tibetan Buddhism depicts deities whose appearance so contradicts the common expectation, that they are immediately misunderstood. The sight of apparently demonic beings dancing on the walls of a sacred temple, alongside the expected images of tranquil deities with gentle faces, both misleads and bewilders uninitiated viewers. As mentioned above, deities may appear in different emanations, in tantric as well as non-tantric form, in which case they are depicted as different beings. The figures of horrific aspect are tantric. Seen within the same gompa, even side by side upon a wall, these contrasting images of serenity and ferocity provide a jolting change of visual rhythm, and an almost emotional dynamism.

These "terrifying deities" apparently derive from several sources. Some, such as Mahakala (see below), were absorbed from Indian Tantrism; others have a native Tibetan origin. According to legend, when Padmasambhava came to Tibet to establish Buddhism, he encountered hostile local gods, whom he vanquished and bound over to serve the new faith. According to various theories, they may have been indigenous gods of the folk religion, or gods from the "old religion," i.e., Bon. Armed and fierce, they guard the entrances to sacred places, combat evil, and show human beings the way to defeat negative emotions that block the way to enlightenment.

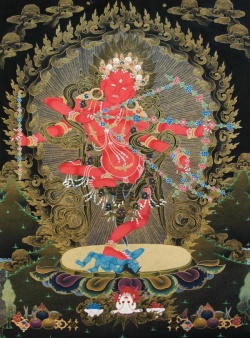

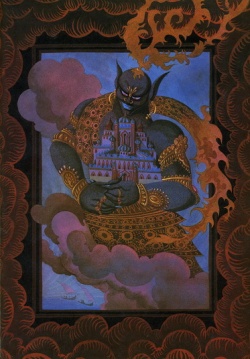

Tantric gods are depicted with thick limbs and powerful bodies, their faces contorted and grimacing, eyes glaring, fangs flashing in their open mouths. They brandish sharp weapons and their feet trample the bodies of small beings in human shape. Their figures are cloaked in flame, their hair and eyebrows ablaze. Some wear a crown of skulls, others a necklace of severed human heads. Some drink blood from empty skulls. Tantric deities may have a single head and two arms, but often they have multiple heads and limbs, and some have animal heads. Uninstructed viewers take them to be monsters, and wonder why they are given such prominent place on gompa walls or in thangkas. But the recognition that deities may take such wrathful as well as peaceful forms is fundamental to an understanding of Tibetan iconology and art. It has also been observed that the terrifying deities harness or sublimate the violence that is a reality both of the cosmos and the human personality.

In Buddhist theory, these deities, although given human form (that is, with arms, legs, and faces) are personified visualizations of energy, determination, and invincible will--abstractions depicted through figurative representation. In the same way, the peaceful deities are symbolic representations of compassion, wisdom, and insight.

The concept that a deity may have several emanations or manifestations, a feature common to both Hinduism and Buddhism, is one of the factors that has led to the multiplicity of divinities. Thus Krishna, for example, is an avatar or incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, and the fierce Vajrabhairava is a manifestation of the Buddhist Manjushri, the great Bodhisattva of wisdom. The great Tibetan deities have multiple manifestations, thus adding to the complexity of Tibetan iconography. The relation of a deity to such emanations is sometimes visually represented by placing above the head of the god a smaller head or figure of the deity with which that god is spiritually connected. Thus, a small image of the Dhyani-Buddha Amitabha is often depicted above the head of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Some of the wrathful gods are manifestations of Buddhas and of the great Bodhisattvas, deities who have what might be described as a dual nature or dual capacity. Yet other wrathful beings have a single nature--an independent identity. In either case, the wrathful, ferocious ones bear arms against destructive, negative forces: the passions of anger, hatred, envy, greed, and pride. They are warriors against ignorance, selfishness and the rule of ego. This is the meaning of the weapons they wield: swords to cut through ignorance, axes to hack down anger, and lassos to snare ego. Spiritual and psychological champions, possessed of tireless energy, their ferocious expressions reveal their determination to repel the subtle delusions that ensnare us, hindering human understanding of truth and ultimate reality, obstructing our path to liberation from suffering.

The wrathful deity Trailokya-vijaya deserves special notice here. Although not one of the very commonly depicted deities, he appears repeatedly in the Jampa mandalas (see Jampa gompa, below). He is "the conqueror of the three worlds," a name signifying his victory over the enemies of the three worlds of the manifested universe: the celestial, earthly, and infernal realms. The primary mandala of Jampa has been identified as the Vajradhatu mandala, whose central deity is Vairocana; however, Trailokya-vijaya is known as an active or wrathful aspect of Vairocana, and as such he appears in several of the Jampa mandalas. (Trailokya-vijaya is referred to in lines 56-59 of the Jampa Inscriptions: see below.) His color is blue and he is generally depicted with two of his hands crossed at his breast in the mudra known as vajrahumkara.

The little figures whom these deities trample beneath their feet are not helpless human beings but rather malignant spirits or representations of those hostile forces that we need to overcome. By their example, the wrathful deities inspire courage and strengthen determination; greed and anger can be defeated, with the same energy and will shown by the warrior god.

Other supramundane beings stand watch at the entrance of a gompa, defending its sacred space against the malicious forces that seek to intrude. Some protect the law, others serve as personal guards, protecting believers against overt attack or the subtle, insidious, seductive dangers that arise within. The great beings, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, use these terrifying forms in order to transform destructive forces and impulses into beneficial spiritual aids.

Yab-Yum

If these ferocious, demonic figures are startling to the uninitated viewer, other tantric motifs and images seem even more shocking or bizarre. Tantric paintings and sculpture often depict a male and female deity locked in sexual embrace, an image known as "yab-yum," or father-mother. Seen without explanation, these images appear erotic and, if considered as devotional art, obscene and scandalous. Rather, the motif is to be understood as a visual symbol of a primary Buddhist teaching, as explained above: that enlightenment is obtained through the union of wisdom and compassion. The figures in a yab-yum image are thus symbolic, the male deity representing compassion, the female representing wisdom (insight), and their embrace is a visual metaphor for the rapture of union. Dualism, the illusory perception of independent existence and origination, is the source of egoism, ignorance, and suffering; union, the goal of the mystic, the fundamental objective of yoga, transcends polarity and leads to bliss. This is bodhicitta, the nonpolarized state, the recognition of indivisible, indestructible truth--enlightenment.

The yab-yum image, although esoteric (and sometimes restricted to initiates) is specific to Tibetan Buddhism, i.e., to Vajrayana, and is a central device in Tibetan art. It found no favor among the Mahayana Buddhists of eastern Asia, and does not appear in the art of China, Japan or Korea. But since sexual union is the fundamental means by which life comes into existence, Tibetans do not see this as an inappropriate symbol for the sacred mystery of ultimate spiritual communion. They were, moreover, influenced by Indian tantrism, with its esoteric doctrines and rituals. Although the female consort of a Buddhist deity is sometimes referred to as his shakti, that term derives from Hinduism, meaning power or energy, and in Hindu tantrism, the feminine is the active principle. Yet in Tibetan Buddhism these are reversed, with the female identified as prajna--wisdom or insight--and the male as means (which relates to compassion)--the means by which enlightenment is obtained, and thus the active component. Yab-yum figures may have a single head and two arms and legs, or they may have multiple limbs. The male figures may be dressed like Bodhisattvas, with ornaments and royal dress, or they may be dressed as Dharmapalas .

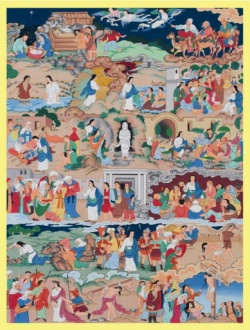

Tibetan art depicts various classes and types of Buddhas, as detailed below. The concept of Buddha has, according to scholars, never been exclusively limited to the "one" historic Buddha, Shakyamuni, who was neither the first Buddha nor will he be the last one. Rather, the Buddha is conceived of in multiple manifestations: not only past and future ones, but also simultaneous appearances, occurring in different, concurrent universes. The Buddhas (the name means "enlightened ones") are the supreme entities in the pantheon, and are envisioned in an unending chain. Thus the artistic motif of the "thousand Buddhas," depicted as rows of tiny identical figures, is a common theme, seen frequently in gompa wall paintings (as at Jampa) and on thangkas.

Buddhism, like Hinduism, conceives not of linear time but of huge cycles or ages. According to Buddhist cosmology, eternity, in its incomprehensible vastness, consists of such innumerable, successive ages, known as kalpas. One such Buddha of a past kalpa was Dipankara, the subject of many legends; very few others are thus named or treated in myth.

Shakyamuni is considered to have had many previous lives. The Jataka tales are legends about his deeds of compassion and self-sacrifice in those previous lives, as well as about his period as a Bodhisattva in Tushita, the Buddhist heaven, before he descended to earth and was manifested as a human being.

As noted above, Shakyamuni is not considered to be the last or final Buddha. The future Buddha, whose arrival in the next age has been foretold, is Maitreya (Jampa in Tibetan), also a figure in many legends. Now waiting in the Tushita heaven as a Bodhisattva, Maitreya will at the right time descend to earth as a Manushi-Buddha (see below) to re-establish the truth and the teachings that lead to liberation. Unlike many of the deities recognized only in Mahayana and Vajrayana, Maitreya is known in Theravada Buddhism. Westerners may think of Maitreya/Jampa as a Buddhist messiah, but this analogy is not accurate. Since Buddhism envisions neither a beginning nor an end, there will be Buddhas beyond Maitreya.

Another identified group are the Medicine Buddhas; the best-known of these is Bhaisajyaguru (Manla in Tibetan), frequently depicted in Tibetan art. His color is blue, and he holds a bowl filled with a special medicinal fruit, the myrobalan. The symbolism of the Medicine Buddha is integral to the concept of Buddhahood, since the Buddha is not only a teacher but also a physician: he understands the illness that befalls the human spirit in its ignorance, and prescribes the saving treatment.

The Tri-kaya (three bodies)

Just as Buddhist cosmology does not conceive of a single, exclusive Buddha, the nature of a Buddha is similarly complex, in that it has multiple aspects. It comprises, according to most Mahayana schools of thought, three "bodies" (kaya). But although the word "body" is a translation of the Sanskrit term, this concept should not be taken to refer to "body" in its common meaning, but rather to a more abstract type of entity. The three kaya can be better understood as distinct, yet simultaneous natures or manifestations. Here again, as with so many other features of Buddhism, its resemblance to Christianity (i.e., the holy trinity) is merely superficial.

In our terms, the kaya may be thought of as three tiers of the Buddha-nature. And, in the highly symbolic world of Tibetan Buddhism, the tri-kaya or three manifestations represent mind, speech, and body:

1. The Dharmakaya, the truth body: the elemental, primordial Buddha-nature;

2. The Sambhogakaya, the glorious or beatific body;

3. The Nirmanakaya, or transformation body: the Buddha in human existence, teaching others the path to liberation.

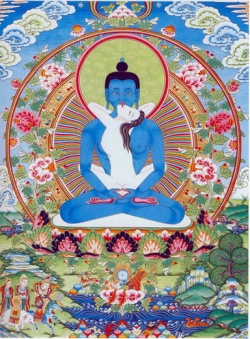

Dharmakaya

This kaya, the truth body, is the ultimate nature, the essence, of the Buddha-mind. This concept signifies the primordial Buddha--infinite, eternal, omniscient, self-existing (swabhava) and self-created (swayambhu), without beginning or end. This primordial essence is variously known, according to the particular sect, as the Adi-Buddha, Samantabhadra, or as Vairocana, Vajrasattva, or Vajradhara. The Adi-Buddha is sometimes considered as the creator of the universe, of whom all things, including all the Buddhas, are manifestations or emanations. In his various forms, the Adi-Buddha is shown wearing the dress and ornaments of a Bodhisattva (see below), but as Samantabhadra, he is dark blue, unclothed and unadorned, as he is above all worldly attributes. He is shown in the pose of union, embracing his consort, who is also nude, and white.

The Buddhas

Sambhogakaya

The five Dhyani-Buddhas (known as the meditation, or contemplation Buddhas) represent the intermediate kaya, the Sambhogakaya: this has been translated as the glorious, beatific, or enjoyment body (signifying the transcendent bliss of the Buddhas). The Dhyani-Buddhas represent the active principle or creative force of the primordial, self-created Buddha, who evolved or created them. (According to some schools of belief, they are not active themselves, but evolved a corresponding set of five Dhyani-Bodhisattvas, who are their active force -- the actual creators of the material world. And some schools consider Adi-buddha as the universal creator, of whom and from whom all things emanate.)

According to some theories, each of the five Dhyani-Buddhas conceived of a different world cycle, for which his Dhyani-Bodhisattva was the actual creator, and for which his Manushi-Buddha or human teacher came to lead that cycle. Ours is the fourth cycle, established by Amitabha, with Avalokiteshvara as its actual creator, and Shakyamuni as its Manushi-Buddha.

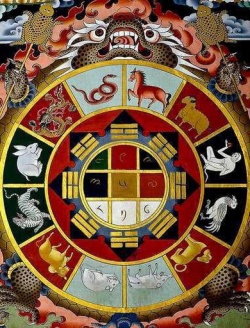

There are five Dhyani-Buddha families. Each of the five Dhyani-Buddhas presides over a different point of the compass and thus they are also referred to as the directional Buddhas. This configuration is a key element in the design of mandalas, as shown in the diagram below. Each is also depicted in his own proper color, holding his own symbolic object, and in his own pose and with his own mudra (hand gesture). Each represents a different element, and a different aggregate (as in sensory, physical or mental faculty, or element of personality).

Whereas the Manushi-Buddha (in our age, Shakyamuni) is shown in the patched robes of a simple monk, without ornaments, the Dhyani-Buddhas are depicted wearing the dress and ornaments of an Indian prince, with earrings, bracelets, and fine shawls.

They are arranged in four corners, corresponding to the four points of the compass, with a presiding deity in the center. The usual set of five Dhyani-Buddhas are as follows: Akshobya in the east, Amitabha in the west, Ratnasambhava in the south, and Amoghasiddhi in the north, and Vairocana in the center. There is also a central or presiding Dhyani-Buddha, sometimes conceived of as a sixth Dhyani-Buddha, who may hover above the center: this can be either Vairocana or Vajrasattva, according to the particular sect. The diagram they form is usually that of a quincunx, turned on its side:

Nirmanakaya

Mortal beings, who are born into this world and leave it at death, can reach Buddhahood, being Buddhas in human manifestation; they are also known as Manushi-Buddhas. As with Shakyamuni, such beings are believed to have advanced through previous lives and incarnations to become Bodhisattvas, and upon their final achievement, supreme enlightenment, reach Buddhahood. In the threefold kaya classification, this is Nirmanakaya, which is translated as the emanation or transformation body -- Buddhas in human form, like Shakyamuni. Such a Buddha achieves nirvana and release from the cycle of birth and death. The Nirmanakaya may also be considered the mortal or human manifestations or emanations of the afore-mentioned Dhyani-Bodhisattvas.

Iconographically, a Manushi-Buddha is depicted in a robe patterned with large squares meant to represent patches -- the simplicity and poverty of a monk's dress -- and without ornaments. A Buddha is considered to have certain physical signs, and is depicted with long earlobes, a protuberance on top of the head, and a small mark in the center of the forehead, between the eyes.

"Tathagata" is a term frequently seen in reference to Buddha, although its precise designation varies somewhat. The Sanskrit word is interpreted as meaning "thus gone," as "so gone," or as "gone in that manner." It is thus taken to signify one who, having thus gone, will not come again, i.e, who will have no rebirths--hence, one who has attained supreme enlightenment. In general, it is one of the titles of the Buddha, and in particular, is often used as an epithet for Shakyamuni in his Nirmanakaya aspect. Some schools, however, apply the term to the Adi-buddha, or to the Dhyani-Buddhas.

Bodhisattvas

Except for the Buddhas in their multiple forms and appearances, Tibetan art is dominated by its greatest deities, the Bodhisattvas. If the Buddhas seem remote in the state of nirvana, the Bodhisattvas represent a type of active Buddha-being, tireless, ceaseless and watchful, who care about and exert themselves on behalf of mortal beings. About Bodhisattvas, David Snellgrove wrote: "The origin of this development, which is special to the Mahayana, is impossible to trace with any precision...." (Snellgrove, Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, p. 58.) A Bodhisattva is one who has reached the threshold of nirvana, meriting the final step into liberation, but who halts, choosing instead to remain in the worldly cycle of samsara, of birth, death, and suffering, in order to help all other beings achieve enlightenment. This is a core Mahayana concept and ideal; the arhat achieves liberation for himself, but the Bodhisattva defers eternal bliss in order to save all other beings. The path of the Bodhisattva is open to human beings, requiring a great vow of dedication, a supremely difficult yet attainable goal.

Early in its development, Mahayana conceived of these celestial Bodhisattvas. The immeasurable breadth and almost unimaginably ambitious goal of the undertaking led the Mahayanists to call their movement "the great vehicle," in contrast to what they termed "the lesser vehicle," Hinayana (Theravada). Few in number at first, the divine Bodhisattvas gradually became too many to enumerate. Among these celestial heroes, three stand out as the great ones, cult figures in their own right -- a triad of archangels. Avalokiteshvara is the Bodhisattva of compassion; Manjushri is the Bodhisattva of wisdom, and Vajrapani of power.

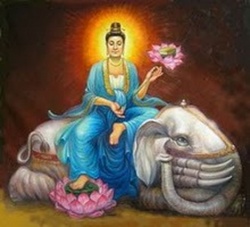

Bodhisattvas appear wearing the garments and ornaments of an Indian prince, with earrings, bracelets, armlets, and anklets, and delicate floating shawls and scarves, as well as a five-leaved crown. Each is depicted with his proper symbol, and often with his proper mudra. To make things more complicated, they have various manifestations, according to which they may each take several different forms, but in their most common forms they are easily recognizable.

Avalokiteshvara (Chen-rezig in Tibetan) holds a lotus and sometimes a string of beads, a sort of Tibetan rosary. The best loved of the Bodhisattvas, he is the symbol of mercy, the greatest of helpers, and the successive Dalai Lamas are considered to be his incarnations. His cult spread north and east, and, transmuted into a feminine deity, he is worshiped as Kuan-yin in China and as Kwan-non in Japan. In one form, Avalokiteshvara is shown with eleven heads, and sometimes with a thousand hands, each with an eye on the palm. This represents the legend attached to his name, "the lord who looks down": in his sorrow at seeing the misery of our world, his head broke into ten pieces; his spiritual father, the Dhyani-Buddha Amitabha, reattached them, and with his thousand-eyed-hands, Avalokiteshvara can see all sorrow and stretch out a hand to each sufferer. In his great compassion and fearlessness, he descended into hell to convert and save the damned, and carried them to the paradise of Sukhavati.

Manjushri (gentle glorious-one; Jampal in Tibetan) with his right hand brandishes a flaming sword, which cuts through ignorance, and with his left carries the book of wisdom, generally resting on a lotus flower. The book is the Prajnaparamita, the fundamental Mahayana treatise on transcendent wisdom. In its customary form, the manuscript is held between flat pieces of wood and the book appears as a long, narrow oblong. According to legend, Manjushri found a great lake surrounded by mountains in what is now the Kathmandu valley. With a great blow of his sword, he opened a gateway through the mountains, through which the waters rushed, thus draining the lake and creating what came to be Nepal. He is the first Bodhisattva to have been mentioned in early Buddhist texts.

Vajrapani (thunderbolt-in-hand; Chana Dorje in Tibetan), as his name indicates, holds the supreme magic symbol, the vajra (dorje in Tibetan). As mentioned above, the device of the thunderbolt is of ancient lineage, the symbol of Indra, the rain god, chief of the Vedic deities, and of corresponding Indo-European divinities. In the development of Mayahana, Vajarapani appears fairly early as a minor deity, a guardian or protector of the Buddha, a being of lesser rank than the exalted position he later attained with the rise of the cult of Bodhisattvas as one of the three great ones. As the supreme warrior of the faith, tireless, relentless, and with inexhaustible determination, he combats demons and falsehood.

Each of these Bodhisattvas also takes several tantric forms.

Female Divinities

The first Vedic gods, such as Indra and Agni, were mostly masculine, but with the ascendance of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva as the Hindu focal deities, feminine divinities arrived and were identified as consorts of the great Hindu triad. These are, respectively, Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, arts and sciences; Lakshmi, the goddess of beauty and wealth; and, as mate of Shiva, god of yogins, Parvati, whose ferocious forms are Durga and Kali, goddess of death.

The earliest divinities of Mahayana Buddhism were, similarly, male, until it began to absorb the influence of yoga and tantrism, as early as the fourth century C.E.

Tara (Dolma in Tibetan), is the first female divinity to appear in Mahayana Buddhism. She is a Bodhisattva, the feminine counterpart of Avalokiteshvara, and like him she is ever-caring, the symbol of compassion, and the source of a cult in her own right. And, like Avalokitshvara, she is the most popular, best loved, and most highly revered of any of the Mahayana or later Vajrayana goddesses. Although she is paired with Avalokiteshvara, they appear as the male and female sides of the principle of compassion, as spiritual mates (thus celibate consorts), rather than as divinity and shakti. According to one well-known legend, a tear from the eye of Avalokiteshvara formed a lake, out of which rose a lotus flower. As the petals opened, the goddess Tara appeared.

Her name signifies her as savior, deliverer. In seeking to trace the origins of South Asian divinities and the sources of religious rituals, scholars have noted resemblances to Persian (Zoroastrian) sources; on the other hand, any correlation with Christianity seems no more than coincidental and superficial. Yet, regarding Tara, more than with any other Mahayanist deity, a correlation with the cult of Mary, the mother of god, is plausible.

Songtsen Gampo, a seventh-century Tibetan king, married two princesses, one Newari (from "Nepal") and the other Chinese, and according to legend, these princesses persuaded the king to introduce Buddhism into Tibet. Tibet's most sacred image, a statue of the Buddha, is said to have been brought to the country by the Chinese princess; it is kept in Tibet's most sacred temple, the Jokhang, in Lhasa. The two wives subsequently became identified as incarnations of the goddess Tara, who it is believed appeared through them in her two main forms: as the white Tara in the Chinese princess; and as the green Tara in the Newari one.

The white Tara is the image of purity and the symbol of transcendent wisdom. Her emblem is the white lotus, its petals open. The green Tara, sometimes considered the original form of Tara, represents divine energy. Her emblem is the blue lotus, its petals closed. The goddesses appear in the dress and ornaments of a Bodhisattva.

The Taras may be depicted alone, or with their partner, and they also appear in tantric, wrathful manifestations. In those forms their colors are yellow, blue and red. These, with Tara's green and white peaceful forms, are the colors of the five Dhyani-Buddhas, of whom these five Taras are sometimes considered the shaktis. These are also the Tibetan national colors.

The goddess Prajnaparamita bears the name of one of the most important of all Buddhist treatises -- the Prajnaparamita -- the book of supreme, perfect wisdom, which she personifies. In the Mahayana tradition, logos, wisdom, is feminine.

Saraswati, although originally a Hindu deity (consort of Brahma, she is goddess of learning, music and poetry), became absorbed into the Mahayana pantheon as a consort of the great Bodhisattva Manjushri. Ushnishavijaya represents a quality similar to that of Prajnaparamita and Saraswati, being the goddess of high intelligence. Besides these, there are great numbers of other goddesses.

Female deities figure prominently in tantric art, and as with male deities, there are wrathful manifestations of peaceful goddesses. When in wrathful manifestation, they are as ferocious and grotesque as their masculine cohorts, grimacing and glaring, with wild hair and fangs, brandishing sharp weapons. And, of course, female beings are required in images of yab-yum, in sexual embrace with a god. Under the influence of Hindu terminology, the word shakti is often applied to these consorts, but they should more properly be called the god's prajna. The concept of the shakti derives from Shaivism, the cult of the Hindu god Shiva and his consort. Through tantrism, Shaivism developed a specialized cult of highly esoteric yoga, replete with sexual symbolism that arose from actual sexual rites reserved for its initiates, which were later transmuted into symbolic ones. Shakti is often translated as energy, which is appropriate for Hindu tantrism, in which the female is the active principle. But this is reversed in Buddhism, in which the male is the active principle, the enabler. The union depicted by yab-yum is symbolically enacted by the two most important tantric Buddhist symbolic objects. The vajra (thunderbolt) and the ghanta (bell), as well as certain tantric rites and initiations, reflect these origins symbolically. (As noted above, the vajra has been likened to a scepter, and to the lingam of Shiva, while the lotus, in place of the bell, sometimes stands for the feminine principle.)

As it came to be believed that devotion to a god was most efficacious when he was in company with his consort, nearly every god, including the Dhyani-Buddhas, was given a female partner, with whom he is depicted in yab-yum attitude.

Among other feminine tantric figures of lesser rank are the dakini. These frequently appear in Tibetan art, sometimes shown standing, but more often dancing or even flying (perhaps for this reason they have been called sky or cloud fairies and even sky walkers), and may be depicted with animal heads. They are sometimes shown in a group or circle.

Protectors or Tutelary gods (Yi-dam)

Believers put themselves under the protection of a yi-dam, a protector, guardian deity, or tutelary god, who becomes one's particular, personal divinity. This is done through a special initiation, under the officiation of a lama. Thereafter, the identity of one's yi-dam is secret. Yi-dam manifest as both peaceful and wrathful forms, and are often represented in yab-yum with their female consort, as, for example, the five Dhyani-Buddhas. Among the best known of the wrathful yi-dam are Hevajra and Kalachakra (Wheel of Time). The wrathful forms have multiple heads and limbs, wear a crown decorated with five skulls, and hold tantric symbols. Their dance, depicted on gompa walls and on thangkas, celebrates triumph over obstructions and the joy of liberation from the bonds of ego.

Dharmapala, Defenders of the Law (The Eight Terrible Ones)

Fierce tantric divinities who fight tirelessly against both demons and enemies of Buddhism, these are the beings of monstrous, even demonic appearance themselves, described above under "Tantric Images." Armed and horrific in appearance, their ferocious faces expressing relentless determination, they are champions of the faith, heartening mortal beings and inspiring fear in evil spirits. They are examplars, models, who show us how to overcome ego and the obstructive passions that cause suffering. Some, like Mahakala, derive from Indian tantrism and were later absorbed into Mahayana, while others are transformations of indigenous or, according to some theories, Bon deities; whatever their origins, these are the hostile gods whom Padmasambhava defeated and then bound over to defend the new faith against all attackers.

Even fiercer in form and aspect than the wrathful yi-dam, the Dharmapalas are among the most startling, dramatic images to be seen in Tibetan art. They are characteristically shown surrounded by a flaming aureole, which represents the tremendous field of energy that emanates from them: their eyebrows and even their hair may also be aflame. Their scowling faces show a third eye, their grimacing mouths reveal fangs. Their fearsome ornaments -- a crown of skulls, a garland of severed heads -- are explained symbolically: the skulls, five in number, are emblems of the negative forces they have slain -- anger, greed, pride, ignorance, and envy, or their equivalents -- and the severed heads, likewise, are trophies of conquest over harmful impulses, misleading thoughts, and malignant spirits. Likewise, the weapons they brandish -- axe, chopper, dagger -- and the lasso they may twirl, show them armed to vanquish, hack, stab, or trap those malicious spirits and destructive attitudes. Beneath their feet, they trample demons, or the old gods and their misleading ways. Some are shown drinking from a skull full of blood.

The Eight Dharmapalas are Beg-tse, Tsangs-pa, Kuvera, Lhamo, Yama, Yamantaka, Hayagriva, and Mahakala, of whom the last five are the best known.

Palden Lhamo: The only feminine Dharmapala, she is as ferocious in aspect as any of them, and brings to mind the Hindu goddess Kali/ Durga. She is shown riding a mule with an eye on its haunch, of which the reins are poisonous snakes. She killed her own son, thus honoring her vow to do so if she could not convert all her people to Buddhism. She is the special protectress of the Dalai Lama.

Yama and Yamantaka: Yama is the lord of hell and god of death. He is sometimes depicted with a water buffalo's head. According to legend, robbers stole a buffalo (in some accounts, a bull) and cut off its head. Entering a cave, they found an ascetic meditating there, and cut off his head to kill their witness. The ascetic seized the buffalo's head and placed it upon his own neck, then killed the robbers and went on a rampage of fury. The terrified people appealed to Manjushri for protection and he, in the tantric form of Yamantaka, conquered Yama. Yama wears a disc, the wheel of the law, on his chest. Yamantaka, with a vajra in his hair, is Vajrabhairava, a wrathful or terrific manifestation of Manjushri -- thus a form of wisdom, the wisdom that perceives ultimate reality, and that which triumphs over evil, suffering and death.

Hayagriva: Known as the horse-necked one, he wears a horse's head in his headdress, and is sometimes winged. The horse is an important Tibetan symbol. The image of the lungta, or wind-horse, appears along with printed prayers on the prayer flags seen everywhere in the Tibetan cultural world, festooning gompas, shrines, houses, and even trees and rocks, where the wind may carry the prayers out across the world. Hayagriva's neighing frightens demons away.

Mahakala: His name signifies the great black one, and as such this important tantric deity is usually depicted, although he also has manifestations in other colors. He may be depicted with a trident, the symbol of the Hindu god Shiva, of whom he is a tantric derivation. Gompas often have a special tantric chamber or even a separate chapel, the Gon-khang, often dedicated to Mahakala; it is restricted to initiates and usually only to men. According to legend, the gods held an assembly to choose the protector of religion, and selected Mahakala. Mahakala has enormous power to overcome all negative elements. The favorite protector-deity of every school of Tibetan Buddhism, Mahakala is a general name, and each school has its own Mahakala, with a name specific to that school.

Guardians of the Four Cardinal Points: Also known as the Lokapala, these are four kings, dressed and armed as warriors, whose images often guard the entrance into a gompa. They may be painted on the wall of the porch leading into the prayer hall or on the internal wall itself, or stand sentinel as statues near the entrance. They are identifiable by their colors and symbolic objects: the white lord of the east holds a lute, the blue or green lord of the south holds a sword, the red lord of the west holds a snake and a shrine, and the yellow lord of the north holds a banner and a mongoose.

In addition to this vast pantheon are yet other minor deities and creatures, also frequently depicted in Tibetan art. Tantric mandalas often include scenes of cemeteries, charnel fields, places where the dismembered dead are left to scavenging animals and birds. A pair of Citipati, dancing skeletons, may appear, mocking illusion. Nagas are serpent gods, snake below the waist but human above. They may display a canopy of cobras, their hoods spread wide, as a headdress; Nagaraja, the serpent king, wears a serpent crown. The serpent in Hindu and Buddhist culture is not always a fearsome creature; when Mara, the evil demon, tried to break Gautama Shakyamuni's meditation, a cobra spread his hood in protection over the Buddha. The garuda is a mythic bird, the "wisdom eagle," known to Hindus as the mount of Vishnu. Composite creatures are a frequent device, especially the makara, part crocodile, part elephant, often seen at the portals of mandalas.

THE MANDALA

A painted mandala dazzles the eye with its intricately symmetrical structure and brilliant color. But however stunning to behold, mandalas were not designed to entertain, or intrigue the eye. The mandala is conceptual art in the same way that the figural images of deities are conceptual: it is a visualization of the nature of cosmic reality, as such sometimes called a cosmic diagram, and a means to spiritual transformation. We must call it "art" only because it is a visualization, a depiction, but it is more than that. Mandalas are tools or aids to meditations. Beyond even that, they are an intrinsic, indispensable element in liturgic ritual, which they do not illustrate; rather, the ritual is conducted through the mandala.

Nothing could be further from the Western relation to art, in which the viewer stands outside the painting, analyzes and perhaps admires it -- an essentially passive and appreciative stance. The Tibetan Buddhist, like Alice in Wonderland, steps through the picture plane and, through a process in which he/she must actively participate, requiring utmost concentration and mental stamina, becomes that of which the center is the symbol. That transformation does not fall spontaneously, as grace, upon the viewer: the practitioner must engage in the process. The mystical experience is achieved, not bestowed.

As with all other forms of Tibetan Buddhist art, the mandala is not a realm for artistic expressionism, but rather the medium for a sacred process: enlightenment, salvation, spiritual transformation. As a mystical painting symbolic of divine order, there is no place in this art for visions of chaos; in Western esthetic terms, the sensibility is classical, not romantic.

Thus these forms or diagrams are integral to understanding Tibetan Buddhism as well as integral to its practice. Since the mandala represents the conceptual core of Jampa gompa in Lo Monthang, this gompa thus represents a statement and a teaching about the nature of ultimate truth -- a school of advanced study. Jampa brings us close to the heart of Vajrayana. Rather than a more conventionally decorated gompa, Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo chose instead to create a special space for initiates.

As the literature on mandalas is extensive, this discussion attempts to set forth some of the main ideas about the mandala: its design, meaning, and purpose.

In its simplest form, a mandala is a mere circle, and is sometimes seen as such, as in a plain, unadorned circle crudely chiseled into the stone doorstep of a house. The circle is an ancient symbol of absolute completeness; in Vedic times it represented the disk of the sun; to Hindus it is a chakra or energy center, and to Buddhists it signifies the wheel of life and the wheel of the law -- the symbol of the teaching of the Buddha Shakyamuni. No mere design or ornament, the mandala circle is inseparable from the concept of a sacred space, made so by ritual enclosure.

A cross may be a symbol of Christian faith, but a mandala is actually a portal into magic. At ceremonies to drive out evil spirits and thus safeguard and purify a home, a lama may sprinkle a substance that has been blessed (usually rice, or any type of grain) around the edges of the room to create a protected enclosure, and he may even sprinkle rice around the shoulders of a person in a protective ring. A thread, blessed by a lama and tied around the neck, becomes a protection cord. An entire community may be protected by a ceremony in which a procession of monks circle the perimeter of the village, sprinkling rice and placing sacred objects at certain corners. The space within has been purified, all demons driven out, and the magic circle is a line of defense, within which there is protection from hostile forces. The space thus ritually consecrated becomes sacred, thus conferring sanctuary, which is inherent in the meaning of a mandala. As the circle delineates the consecrated space, the ritual motion appropriate to such a place is encirclement, and Tibetans perform "kora," or circumambulation, around any holy object, be it a prayer drum in a village chapel or Mt. Kailash, the sacred mountain, around which pilgrims walk (or perform full bodily prostrations). The orthodox circumambulate clockwise, while the Bonpos make their circle counterclockwise. It is thus in a clockwise direction that one should process through a gompa, itself a three-dimensional mandala, a place of sacral purity.

Not only does a mandala confer protection, but with the proper rituals and proper use, it also confers power.

Beyond those simplest of mandalas -- the circle incised on a doorstep, the ring of grain around a room, or the ritual demarcation of a protected space, are the complex, intricate, beautiful, and often mystifying images painted on thangkas or on gompa walls, or painstakingly created on a floor from particles of colored sand. Just as for drawing the image of the Buddha, both the space and the artist must be prepared by certain rituals, and the image itself drawn with mathematically exact proportions in order to serve as a spiritual medium, so there must be ritual preparation before the drawing of a mandala. The surface must be purified and the space consecrated by the appropriate rites, the outline of the mandala drawn according to precise rules, and the makers of the mandala must take certain vows. The magnificent diagram about to be delineated and then colored is not about magnificence -- its beauty being incidental. It must be consecrated and empowered if it is to serve its sacred function, spiritual transformation.

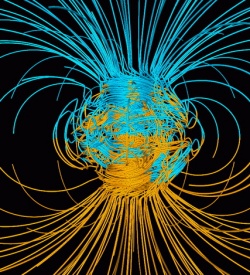

The defining element in the design of a mandala, no matter how complex, is symmetry. Enclosed within the mandala's outer circle may be an intricate pattern of circles, squares, and triangles, but they must adhere to the fundamental rule of geometric symmetry. In this way, the mandala becomes the visual expression of the Buddhist belief that the core principle of the universe is unity, deriving from the inter-relatedness of all phenomena. Human beings are constantly distracted and misled by the chaos of the mundane world and the multiplicity of phenomena, mistaking the impermanent as if it were lasting, and confusing illusion with reality. The ultimate reality is the interrelatedness of all phenomena -- an indivisible whole, the quintessential unity. And since the mandala is a teaching and a representation of non-duality, of unity, therefore order and harmony are intrinsic to its design. As an emblem, the mandala is the key to discerning the divine order of ultimate reality, and to refuge in this hidden truth.

However numerous the beings depicted in a mandala, at the center is one deity (whether single, in yab-yum, or represented by the deity's abstract symbol). And however complex the component parts of the mandala, they are concentric, so that movement from any part of the mandala leads to its central point, which is the symbol of the One, the cosmic unity, the matrix. This is the still, silent, dimensionless point at the heart of reality, undisturbed by the outer chaos. And since harmony, order and serenity are the qualities sought by the practitioner who uses the mandala, it must, through its structure, be a visual emblem of such harmony. However exuberant in its figures and complexity, the design of the mandala is controlled. Through its purity of line and concentric, symmetrical order, the mandala focuses on the essential nature of reality.

Although we most often see a mandala in two dimensions, painted on a wall or thangka or created on a floor or flat surface, it is meant to be visualized as a three-dimensional structure, for which it is effectively a blueprint.

Mandalas are sometimes, although more rarely, created three-dimensionally, sometimes in bronze. The great stupa of Borobodur in Indonesia is a gigantic stone mandala. (The origins of the stupa have been linked to ancient cultures, such as the Mesopotamian Ziggurat, also a cosmogram of the universe, layered into a certain number of terraces with astrological correspondence.) Because of the ancient correlation of the royal and the sacred, of the king endowed with priestly functions, and of gods in royal capacities (e.g., Zeus/Jupiter or Indra), the mandala is thought of as both palace and temple, or even as a royal city, or, in two-dimensional form, as the blueprint for such a palace or temple. Indeed, Shakyamuni is termed Chakravartin, the Universal Monarch. In the center of the mandala, the deity sits in splendor upon a throne, surrounded by supporting divinities, like an earthly king surrounded by his court, in princely dress and ornaments. That a mandala should be thought of as a blueprint is more than an abstract conceit, since liberation is not given by grace, but must be achieved by concentrated effort, by action both mental and spiritual. The participant makes his or her way by a gradation of steps into and through the palace/temple to the presiding deity at the center.

Just as there are deities almost without number, there is a profusion of mandalas, although each conforms to the basic format of symmetry and concentricity. Again, this is not because artists wished to outdo each other in devising and designing new patterns of the form. Rather, each of the five Buddha "families" (the Dhyani-Buddhas) has its own special mandala, as does the presiding deity, and there are other mandalas for the other gods in their multiple manifestations and emanations. Various mandalas are appropriate to particular persons, to the spiritual condition the adherent wishes to achieve, or to the particular obstruction that he/she wishes to overcome -- not by repression but through transfiguration -- such as passion, anger, greed, etc. A neophyte must undergo a tantric initiation during which, with the help of a guru, the person's Buddha family is determined, and a mandala is chosen that corresponds to that family.

Thus we approach the function and the practice of the mandala. Its meaning returns us to yoga, and the tantrist philosophy that underlies Vajrayana or Tibetan Buddhism. The mandala is a yogic painting, and the goal of yoga is union with the supreme essence, the One, the All, the Absolute. And the object of the Buddhist practitioner is to become one with the god of the mandala, the deity at its center. If successful, this is the power conferred by the mandala: transformation into the divine being and thus sublimation into the spiritual state of which that deity is the symbol.

In a further layer of conceptual complexity, the transformation thus achieved is found within the self. In this belief, the microcosm and the macrocosm are held to be one. The human body itself is considered a mandala, and because of this correspondence between the microcosm and the macrocosm, the individual can correspond to a divinity. The Buddha-essence or Buddha-nature is already latent within each person: the task is to reveal it. In serving as a channel for transformation, the mandala offers a means of re-integration into the state of Buddhahood.

None of this happens by simply looking at a mandala; as mentioned above, the process is active, not passive. The practitioner uses a set of mental and spiritual exercises in order to recreate within the mind what the mandala symbolizes and thus to achieve that spiritual condition. Here it is necessary to consider the conventional format of the mandala.

Its outer border is a circle, usually a set of concentric outer rings. Within the innermost ring is, most often, a square, which is itself often dissected by two diagonal lines into four triangles. This inner square corresponds to the palace of the deity, within which is an inner circle, the seat of the divinity. The diagonal lines through it have been interpreted to symbolize the axis mundi, Sumeru -- the cosmic mountain at the center of the universe -- and the human spinal column, the microcosm assimilated to the macrocosm.

The palace (represented by the inner square) has four T-shaped gates or portals, each surmounted by a torana or triumphal arch, Above these gates appear certain conventional images and ornaments, both symbolic and ornamental, as befits a palace both royal and divine. A disk represents the wheel of the law, two gazelles symbolize the deer park in which the Buddha Shakyamuni gave his first teachings, the parasol is the insignia of royalty, as are the ornamental streamers and strings of pearls, etc.

This structure is used to guide the practitioner through the psychic process of the mandala. Through a set of meditations, with the blueprint of the mandala as a structural support, the adept enters the mandala by passing through the outer rings, then enters the palace through one of its portals, and proceeds by stages to the inner sanctum, to the throne itself and the deity upon it, and then, achieving through intense concentration the supreme transformation, becomes one with the divinity and that which the god represents.

The solitary adept may "enter" the mandala and undertake the process independently, in concentrated meditation, but the neophyte requires initiation and the help of a guru. These initiation rituals are complex and elaborate. As they dealt with a rather magical process and the acquisition of powers, they involved secrecy and were reserved for those who were initiated into the tantra through its mandala. There are particular initiation rituals for particular tantras.

With appropriate sacraments, the guru or master prepares the student, who must have the intention of using the powers he will gain not for his own salvation, but to help all other beings, thus following the way of the Bodhisattva. Initiation into the mandala proceeds by stages, including a water initiation, resembling baptism, and another in which the neophyte is crowned, reflecting the correspondence between the sacred and the royal.

Although the Kalachakra Tantra is only one of the many tantras, it has become the best-known because the Dalai Lama has been traveling around the world giving the Kalachakra initiation. Before the ceremony (which lasts for several days), the space on which the mandala will be constructed and the monks who will create it are purified. The monks then construct the Kalachakra mandala according to special rites and in the exact design, proportion, coloration, etc., of this particular mandala.

Since these are mass events, held in theaters, stadiums, or vast outdoor spaces, attracting thousands of people, the rites cannot be performed as they were designed, for the individual supplicant or neophyte who would take part in the ritual. Instead, they are enacted symbolically for the crowd. Many of those who attend simply want to be in the presence of His Holiness (whom they will most likely only glimpse from a great distance), and may have only the vaguest understanding of what is transpiring. But it is worth understanding, if not the entire process and its complex, esoteric symbology, that there is an ordered structure to the initiation, and that the tantra and its mandala are indivisible. Since the crowd cannot pass as individuals through the stages of the initiation, the Dalai Lama uses these events as a mass teaching, stripping away the arcane and esoteric, interpreting the Kalachakra's basic concept and message.

Tucci considered such rites of initiation as being "liturgical dramas," (one may think of medieval mystery plays), during which, at the decisive phase, the divine force descends into the master, who can then confer it upon the student.