Monastic

1. Of, relating to, or characteristic of a monastery. Used often of monks and nuns.

2. Resembling life in a monastery in style, structure, or manner, especially:

a. Secluded and contemplative.

b. Strictly disciplined or regimented.

c. Self-abnegating; austere.

1.

of or pertaining to monasteries: a monastic library.

2.

of, pertaining to, or characteristic of monks or nuns, their manner of life, or their religious obligations: monastic vows.

3.

of, pertaining to, or characteristic of a secluded, dedicated, or austere manner of living.

noun

4.

a member of a monastic community or order, especially a monk.

[1]

Daughters of Wisdom:

Sometimes a person may feel so strongly dedicated to the Three Jewels and so averse to samsara, that he or she would like to devote his or her life to Buddhist practice. One does not have to become a monk or nun to do that, since there is "room" in Buddhism for practitioners of several types with various levels or types of commitment.

Preparation for Taking Vows of Aspiration

Having experienced the veracity of the Four Noble Truths and through contemplating the Four Thoughts (that turn the mind to Buddha Dharma,) some yearn to renounce cyclic existence (Skt. sangsara, samsara) entirely. The situation most conducive to this is found in retreat or in a monastic order, where we can practice uninterruptedly.

To prepare for this, a person needs to withdraw from social commitments and clear up outstanding personal business including financial debts. This is the first step in abandoning worldly activities entirely.

Why Join a Monastic Community?

In the Mahayana, the quest for Awakening is not for oneself alone, but out of a sincere wish to benefit all sentient beings without exception. Thus, after taking Refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha (the Three Jewels,) the bodhisattva vows are the first ones we take. A logical next step may be to seek to join a monastic community where one can dedicate one's time and energy to dharma study and practice in a situation where we are free from the distractions of daily life. Through this practice, we can better help others.

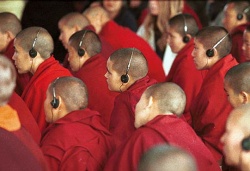

In a monastery, one is more likely to have regular access to teachers with expertise than as a "householder." Also, there the circumstances are more favourable to one's receiving individual guidance from a mentor and to receiving Vajrayana transmissions on a regular basis. Ever since the Buddha's day, the sanghas of monks and nuns have been the primary holders of the Dharma because this. And the presence of Buddhist monastics in a community serves as inspiration and motivation for others to learn about, to study and to practice the Dharma.

Vows

Vows which monks (Tib. gelong) and nuns (gelongma) take are called "Personal Liberation" vows and are founded in the commitment to absolutely refrain from doing harm to others. Therefore we promise to abandon certain activities and to uphold the ideals of highest morality. Such vows are to be treated as life-long.

Pratimoksha Vows interpreted for modern "laymen" (Theravadin tradition.)

While a man can take temporary (getsul) monastic vows of renunciation several times in his life, the rule is that a woman can only do so once. Therefore, it is important to talk over the idea with a knowledgeable spiritual mentor.

If a fully-ordained person changes his or her mind, it is not enough to take off one's robes in order to be released from the commitment. The vows must be formally given back to another monastic, who is still holding his or her vows. To break these root vows is considered to cause serious consequences in terms of karma, and overcoming them is rarely possible in just one lifetime. Therefore, for men, a preliminary stage that can be temporary, that of getsul, was introduced. For women, see below.

How to Become a Monk

In order to take Buddhist precepts and vows of renunciation, one must, in person, make a formal request to a master who is qualified to administer them. Also, the vows must be taken in the presence of 4 fully ordained* monks. The master will assess whether a person is sincere, is fit and mature enough and, if the person is young, inquire whether he has the permission and the support of his family in this endeavour.

<poem>

"Your best bet may be to check the schedules of some of the larger,

more well established centers, to see when the next "Big Rinpoche

tour" is coming through -- and try to find out how many monks will be travelling with him. If there are at least five, you may be in luck.

Try to contact the tour coordinator, and see if you can arrange for

the ordination somewhere along their tour -- this is exactly what I

did. You'll need to provide your own monastic robes for the ordination* . . . ."

~ James to the Yahoo! Kagyu group, Sept./04

Sometimes a prospective postulant is asked to wait a few years to ensure that he is not "running away" from some problematic situation. Some people may find it beneficial to follow some of the main principles, such as rising early, limiting eating habits and keeping celibate, to see whether they are actually suited to a life of monastic discipline.

It is not absolutely necessary to receive the vows in the denomination or lineage to which one is devoted. This is especially true in the West, where we do not often have the opportunity of having access to our root lamas. All Buddhists are considered members of the sangha of Shakyamuni; he is our ultimate Refuge.

The Distinctive Case of Women

For ordination, the woman's situation is different, deriving as it does from ancient Indian cultural tradition: Her body is a door to the continuity of samsara and rebirth in this realm, and she does not have absolute control over conception.

Ani Chu-Yeshe's story.

In Tibetan, they say "If you want a teacher, you should make your son a monk. If you want a servant, you should make your daughter a nun. You should know that, like their male counterparts, Buddhist nuns observe over 200 precepts, but they must observe several more than the monks, and are always considered subordinate to them.

Traditional nuns and monks are members of a community, and there is good reason for that.

In the Americas and in Europe, there is not much financial and social support yet for Buddhist nuns. Also, as some other spiritual traditions, there are lengthy periods of being a postulant and then, a novice (Skt. shramanera.) Until 1981, for various historical reasons full ordination* (Skt. bhikshuni, Tib. gelongma) in the Tibetan tradition was not possible, so you will need to find out about that, too.

Khenmo Drolma's experience getting full ordination in Taiwan

- ordination is not a Buddhist concept. The term has been frequently used because it is familiar to people who know about monasticism within the Christian (Catholic or Anglican) context. In Buddhism, one renounces the activities of "family life" by beginning with the observation of some fundamental precepts and then later, if one chooses and is able to do so, vowing to keep all the commitments of renunciation.

Life as a Buddhist Nun

Ven. Thubten Chodron, a Western woman teaching in the Gelugpa tradition.

Ani Konchok Drolma on the community at Gampo Abbey, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Read about Ven. Pema Chodron at the above link, too.

"With Robes and Bowl," lifestyles and kinds of practices.

Ani Tenzin Palmo (Drukpa Kagyu)

Supporting the Aspiration of Someone Else

If you cannot go into retreat yourself, why not consider helping someone else? Retreatants usually require financial sponsorship before being accepted. There are several good reasons for this, not the least of which is that it keeps alive the tradition upon which the Buddhist monastic community was based. That is, it fosters generosity and support for the dharma in the wider community. This support gives one an opportunity to practice generosity and to share in the merit of the person doing the retreat.

For example, in spring 2003, Pema (Kate White) needed help completing the 3-year, 3-month retreat at Karme Ling in Delhi, NY, USA under the direction of Ven. Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche (Abbot of Karma Triyana Dharmachakra). It costs about $575 each month to defray the expenses of food and lodging.

If you are able to help any retreatant in need, please consider:

Karme Ling Retreat Center 315 Retreat Rd Delhi, NY 13753-9304

Supporting a person in retreat is considered as meritorious as if you yourself are doing the retreat. One Tibetan Nun's Story

Finally, in spring 2003, Ani Ngawang Sangdrol was released from Drapchi Prison where the PRC had sentenced her to an ever-extending term. An extract from her statement:

I am deeply touched to learn that many individuals,

organizations, and governments, particularly the

United States, France and Switzerland, have worked

towards my release. It is very clear to me that I have

been released and allowed to come out to the free

world for medical treatment and to enjoy my freedom

because of international concern. Even as I enjoy this

freedom I am concerned about the many more Tibetan

political prisoners, including my fellow nun [[Phuntsok

Nyidron]], languishing in Chinese jails. I am presently

compiling information about the conditions of these

Tibetan prisoners. I am committing myself to doing

everything possible so that they too can be released

and can enjoy freedom, just like me. I appeal to the

international community to help give them freedom.

I pray that His Holiness the Dalai Lama's efforts

towards the resolution of the Tibetan problem will

have early results. I will abide by any advice His Holiness may have, so that I can best contribute

towards the fulfillment of his wishes for a solution

to the just cause of Tibet. The Tibetan people in

Tibet are eagerly waiting for the day when they can

see the return of their beloved leader to their

homeland, with dignity, freedom and respect.

Ngawang Sangdrol, Washington, D.C., Royal Tibetan Year 2130, 7th day of the Second Month: April 9, 2003.

On March 31, 2003, in a Tibetan language interview, Ngawang Sangdrol described the intense official surveillance that followed her early release from prison in 2002 -- nine years before her sentence was due to end. "After I was given medical parole from prison, there were still guards watching me all the time, even at home." She said guards beat her on many occasions, once smashing mugs and plumbing pipe on her head until it bled heavily. She had to agree not to engage in "anti-Chinese" activities overseas.

Now in her mid-20s, ani Ngawang Sangdrol was first detained at age 13. She was paroled from Drapchi Prison on Oct. 18, 2002, nine years before completing her sentence. As a nun at Garu nunnery, she took part in pro-independence demonstrations in Lhasa in 1987-88. Her sentence was extended three times to a total of 21 years after she and other nuns engaged in prison protests.

At one point during her detention, she and 13 other jailed nuns secretly tape-recorded songs touching on their love for Tibet and for their families. A cassette was smuggled out which became very popular in the West, and Ngawang Sangdrol's sentence was extended by six years.

The story of the incarceration of the outspoken young women is told in Windhorse (1999), a film that was in part made surreptitiously.

</poem>