A Teaching on the Essence of the Tathagatas (The Tathagatagarbha)

Instructions on

A Treatise entitled: “A Teaching on the Essence of the Tathagatas

(The Tathagatagarbha)”

by the Third Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje,

according to

An Illumination of the Thoughts of Rangjung Dorje:

A Commentary to “The Treatise that Teaches the Buddha Nature”

by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye the Great

Translated from Tibetan by Peter Roberts

Presented at the Namo Buddha Seminar in Oxford, 1990

Introduction

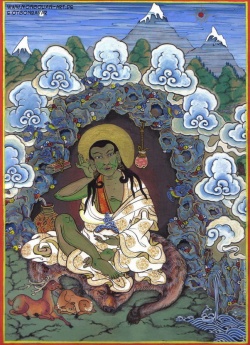

In a prophecy, Naropa told Marpa Lotsawa that in his Lineage the pupils would be greater than their teachers. The First Karmapa was Düsum Khyenpa and the Second Karmapa was Karma Pakshi, who had greater power and more miraculous abilities than the First. Basically,

both the First and Second Karmapas were in essence the same, but it appeared as though Karma Pakshi was more magnificent. In the same way, the Third Karmapa, Glorious Rangjung Dorje, had even greater qualities of learning and miraculous abilities. There are seventeen

Karmapas and among them Rangjung Dorje was the greatest scholar. In fact, two Karmapas showed immense learning, experience, and realization; they were Rangjung Dorje, the Third Gyalwa Karmapa, and Mikyö Dorje, the Eighth Gyalwa Karmapa. Mikyö Dorje demonstrated great

knowledge and realization of the sutras, and Rangjung Dorje demonstrated great knowledge and realization of the tantras.

Rangjung Dorje was a master of the Kalachakra teachings. He had the experience, realization, and clear knowledge of the movements within the body, of the nadis (“the channels”), the vayus (“the subtle winds”), and the bindus (“the subtle essences”). He understood them

quite clearly as they are taught in the tantras and he composed the text, The Deep Inner Meaning - Zabmo-Nangdön. Here he described all the highest tantras, the Anuttaratantras, which consist of the father, the mother, and the non-dual tantras. Since Rangjung Dorje had

mastered the Kalachakratantra, he understood astrology and therefore the movements of the sun, moon, and stars on the basis of his knowledge of the nadis, vayus, and bindus within the body. He therefore composed astrological texts based upon the Kalachakratantra, which

clearly explained the movements of celestial constellations. These texts are exceptional, because they illuminate the movements of the planets, solar system, lunar eclipses, etc.

Rangjung Dorje wrote two treatises, which are branches of the Zabmo-Nangdön. These two shastras are Transcending Ego: Distinguishing Consciousness from Wisdom and The Teaching on the Tathagatagarbha, the text presented here. In the first shastra, the Glorious Third Karmapa showed the difference between the various types of consciousness and wisdoms; in the latter he showed how the Buddha nature is present within all living beings.

1. An Explanation of the Title

All living beings born in the world see it as their birthright and duty to experience happiness. But they experience the suffering of ageing, sickness, and death. Alternating between surprise and disappointment, the only liberation from anxieties arising from dual

experiences that burn continuously is recognizing and removing own imperfections and evolving instead of remaining self-involved. His Holiness the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, therefore wrote The Treatise entitled: “A Teaching on the Essence of the Tathagatas (The

Tathagatagarbha)”.

Let us look at the Sanskrit word tathagatagarbha, which is de-dzhin-gshegs-pa’i-snying-po in Tibetan, to understand well what letting go in order to release the true nature means, which is the goal.The Sanskrit means “the womb,” garbha from the root word garbh, “to

conceive” (which in pure Sanskrit can also mean “the interior, embryo, foetus”) of the Tathagatas, i.e., “the place from which they are born.” Tathagata is comprised first of the syllable tatha, which means “in that manner, in that way, so, thus.” The second half of

the word has been interpreted to be both gata, “gone,” and agata, “come,” as the same result comes from the combination of tatha with either word. However, gata as the conclusion of the compound word normally has the meaning of “to be” something or somewhere, so that

the term would mean “one is thus” or “like that.” Therefore, although the Sanskrit can mean, “to be in such (a state or condition),” it has been glossed and translated literally as “one who has come and/or gone like (the previous Buddhas),” i.e., a Buddha. The Chinese

translation of the term tatha followed the interpretation “one come in that way,” while the Tibetan de-bzhin-gshegs-pa followed “one gone in that way.” The word garbha was translated into Tibetan as snying-po, which means “essence,” so that the Tibetan term literally

means “the essence of the Tathagatas” (instead of “the womb or embryo of the Tathagatas”). The Standard English translation of either the Sanskrit or Tibetan is “Buddha nature.”

The Third Karmapa wrote the treatise that explains the Buddha nature so that disciples and pupils let go of their sense of being separated from the external world and give rise to and manifest kindness and goodness instead. Rangjung Dorje taught about the essence of

the Tathagatas, one could also say Sugatas, and called the treatise The Sugatagarbhashastra.

Sugata means “gone to bliss.” In order to win the peace of bliss, it is necessary to follow in the footsteps of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. In this regard, a spiritual teacher who has attained wisdom and bliss can - through setting examples, presenting instructions,

and offering guidance - show the way. Can ordinary beings reach the same goal the Buddhas have attained? Just as the Buddhas and Sugatas tread the path and have gone to bliss, every living being can, because the Buddha nature is innately ours.

The term Sugata refers to bliss, which, in turn, points to suffering and pain. The term Tathagata, in contrast, means “one gone like that” or “one gone thus.” This means that when a Bodhisattva has realized Buddhahood, he or she has not only gone to bliss but has

naturally manifested his or her true nature - bountiful virtues and values of lasting worth.

All living beings possess the Buddha nature, the pure essence. Everyone can attain a state of bliss that opens and yields ineffable qualities. How? By meditating. There are the Dzogchen and Mahamudra meditation instructions in the Buddhist Tradition. One needs to

receive these instructions from an authentic spiritual master and guide, someone who can reliably show the way. If one receives meditation instructions, understands them correctly, and knows how to practice, then no difficulties will arise. If one does not understand

the instructions clearly, then practice will be very difficult. This is the reason why the instructions on the Buddha nature were given.

In the commentary to this text, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye the Great stressed the importance of knowing why one engages in meditation practices. The reasons are presented in the teachings on the view, which is won by studying the texts. He stressed the significance of

practicing meditation with the correct view, otherwise one would resemble someone who tries to climb a steep mountain cliff without any hands. Similarly, he compared someone who has won certainty of the view but does not meditate with a rich person who hoards his

wealth out of miserliness. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye wrote that if one practices both disciplines, namely gains certainty of the view by studying the instructions and meditates correctly, then a disciple resembles a bird flying through the sky with two wings fully in

tact. He tells us that the right wing of the bird is meditation, the left wing is knowledge, and when both wings are healthy the bird can fly freely. This is the reason why the Third Karmapa wrote the treatise on the Buddha nature - so that disciples are inspired to

attain unity with their own brilliant treasure that is ever present and true.

2. Why Shastras Were Written & Nine Categories of Shastras

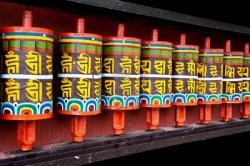

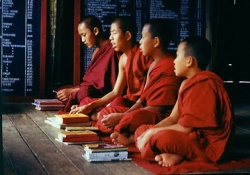

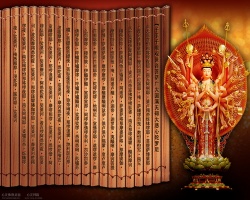

In general, the discourses presented by Lord Buddha are collected in the Kangyur, “The Translation of the Buddha’s Word,” or sutras (Sanskrit for the Pali word sutta, “scripture”). The three traditions of Buddhist scriptures are the Theravada, the Chinese, and the

Tibetan. In particular, the Chinese masters emphasized the sutras and criticized the shastras (bstan-bcos in Tibetan), which are the “written commentaries” by Buddhist masters that are collected in the Tangyur, “The Translations of Teachings”; they said that they are

not valid. The Vajrayana masters of Tibet always recognized and honoured the importance of the shastras, because the scholars who composed them did not write something different than Lord Buddha’s words. The Tibetan version of the Tangyur consists of more than 100

volumes.

The vast collection of scriptures are named after the place where they were printed and published. The complete Kangyur was first published in Beijing in 1411, the first Tibetan edition was printed at Narthang in 1742 and consists of 98 volumes. The Narthang Tangyur

contains more than 3600 texts with stories, commentaries on the tantras and sutras, discussions on Vinaya and Abhidharma, logic, rhetoric, grammar, literature, biographies, painting, medicine, chemistry, and astrology. The Derge Kangyur was edited by Situ Panchen

Chokyi Jungney and was completed in 1744 by Tsultrim Rinchen. The Derge Collection was printed at both the Printing Academy and Palpung Monastery in Derge, West Sechuan, the latter treasured in most monasteries, hermitages, and temples in Tibet and Mongolia the most.

It was because of these collections of Buddhist wisdom that the Mahayana tradition survived through many centuries, from the time that the translations began in the 8 th century until now.

Why were the shastras written? One reason why the shastras that are collected in the Tangyur were written is because the Buddha’s teachings are so vast and a beginner would find it very tedious to gain an understanding of a specific topic from the original texts

collected in the Kangyur, which are not organized in an accessible way. The Buddha replied to individuals who asked questions in different places and under other circumstances, therefore the teachings are answers to specific questions. Pupils living somewhere else

asked other questions and received different answers. The vast amount of teachings are therefore scattered throughout the sutras and not organized according to topics in a single volume, so it is not possible for us to learn what we wish to know from the many sutras.

This is the reason why great masters composed treatises in which they collected and compiled a subject matter from the various sources into one text. A shastra deals with one subject found in many sutras. This is one reason why the shastras are important and precious -

a specific topic is accessible.

Furthermore, shastras clearly explain profound subjects. Some pupils think that only knowing what the Buddha said suffices and have deep faith, while other pupils are more inquisitive. For example, in The Prajnaparamitasutra we read, “There are no eyes, no ears, no

tongue (…).” Some students have conviction in this statement and rely upon the Buddha’s words. Others wonder and seek explanations from qualified teachers. Scholars wrote texts to explain the meaning and logically prove why such statements are valid and true.

Another reason why shastras were written was to hinder a decline and distortion of the precious teachings. Some sutras may be lost or not translated into Tibetan; other sutras only contain certain answers to specific questions. In order to prevent degeneration of the

Buddha’s words, a great master wrote a treatise in which the entire subject

would be covered. These are three reasons why Rangjung Dorje and other great masters wrote shastras.

There are many different kinds of shastras. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye the Great defined nine categories:

(1) Meaningless shastras are texts that, for example, go into detail to argue whether birds have teeth or not. Such literature is of no help to anyone and does not encourage spiritual practice. Studying them is of no help or benefit to anyone.

(2) Incorrect shastras convey wrong meanings. For instance, there are texts that try to explain that if one dies in a war, one will attain liberation, but dying in anger and rage that every war always entails is of no benefit to anyone at all.

(3) Meaningful shastras convey beneficial thoughts. Studying this type of treatise will definitely be good.

(4) Deceptive shastras mislead people. There was once a king in ancient India who had a beautiful daughter he wished to see married, so he wrote a text in which he said that things happen for no reason at all and haphazardly. He argued that peas are round and thorns

are sharp without a cause, implying that even though his daughter grew up in a hothouse atmosphere, there would be no reason to worry about marrying her.

(5) Heartless shastras are texts that have no compassionate message. Once I came across a group of Hindu ascetics at the Marataka Caves who were sitting around a burning log and inhaling the smoke. I asked them why they were doing this, and they answered that they were

practising asceticism just as they had read. Now, a teaching of this kind only causes suffering for such practitioners and does not help anyone at all.

(6) A shastra that instructs how to eliminate suffering is a treatise that shows how to become free from the temporary suffering of conditioned existence and how to achieve lasting freedom from discomfort and discontent.

(7) A shastra devoted to learning is a treatise that helps gain an understanding of a subject matter.

(8) A shastra dealing with debate is a treatise that teaches how to discuss various opinions through refutations and proof.

(9) A shastra devoted to spiritual practice is a treatise that brings lasting benefit. Shastras seven and eight offer temporary well-being, while number nine teaches how to practise so that one gains reliable, beneficial results.

There are six types of shastras that one does not need: 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8. One needs the treatises that have a meaning, that show how to eradicate suffering, and that are devoted to helping us practice: numbers 3, 6, and 9.

The tradition of writing shastras originated in India, where scholars would compile and comment specific subjects presented in the sutras. In Tibet, another tradition arose and developed. Masters would commence a commentary by first composing an outline of the entire

text they were presenting. Their treatises begin with a short summary, and then they wrote a detailed explanation. This approach makes it easier for the teacher and for students. It is difficult understanding an outline which summarizes an entire text, often referred

to as “root texts,” and that is also why shastras were written.

3. Homages in Traditional Texts

In the Buddhist tradition, it is the custom when writing a treatise to begin with the name of the treatise, then to pay homage, and often to pledge to write the treatise. This is done so that the author doesn’t encounter any obstacles while writing a book and so that

the text presenting the Buddha’s words benefits others in the future without any hindrances. The supplication is written with the wish that when it is finished and others study, contemplate, and meditate it, they will encounter no obstacles but will be able to master

the training and practices that the author hoped to convey.

First there is homage to the Three Jewels – the Buddha as the teacher, the Dharma as the body of teachings, and the Sangha as all noble friends assisting and accompanying one along the way. In Buddhism, it is recognized that a Buddha is someone who has achieved the

state of realization through having gradually proceeded on the successive stages of the path. While on the stages of the path he or she is a Bodhisattva. Therefore, there is the homage to the Buddhas who have completed and to the Bodhisattvas who are on the path. The

homage in the Sutra Tradition that Noble Rangjung wrote to commence The Tathagatagarbhashastra reads:

I pay homage to all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

The homage that Shantideva wrote in The Bodhicharyavatara is:

“To those who go in bliss, the Dharma they have mastered and to all their heirs,

To all who merit veneration, I bow down.

According to tradition, I shall now in brief describe

The entrance to the bodhisattva discipline. ” (Shantideva, The Way of the Bodhisattva. A Translation of the Bodhicharyavatara. Translated from the Tibetan by the Padmakara Translation Group, Shambhala, Boston & London, 2002, page 33.)

A few verses from Shantideva’s sincere offerings are:

“To the buddhas, those thus gone,

And to the sacred Law, immaculate, supreme, and rare,

And to the Buddha’s offspring, oceans of good qualities,

That I might gain this precious attitude, I make a perfect offering.

I offer every fruit and flower

And every kind of healing medicine;

And all the precious things the world affords,

With all pure waters of refreshment;

Every mountain, rich and filled with jewels;

All sweet and lonely forest groves;

The trees of heaven, garlanded with blossom,

And branches heavy, laden with their fruit. ” (Ibid., page 29.)

When paying homage, there is the understanding that the Buddha has two qualities. These two qualities address the two sides of existence, being and becoming. The first side points to the fact that ordinary living beings have the three negative kleshas (Sanskrit for “

mind poisons”), which are ignorance, aggression, and desire. The second aspect is that ordinary living beings possess the pure qualities of knowledge and love for others, small in comparison to the mind poisons. The positive qualities gradually manifest when a

practitioner relies on the remedies to decrease and eradicate the kleshas the moment they arise or before they grow. When the negative kleshas have been eliminated, then there is attainment of Buddhahood, the state of a perfect Buddha, which is enlightenment.

The Tibetan word for “cleansed” is sang, the first half of the name for Buddha. When all faults have been removed, then the positive qualities manifest; they are wisdom, love, and great compassion for all living beings. Love and compassion encourage and empower one.

All qualities of being and becoming develop and increase through the cleansing process of practice. The Tibetan word for “developing and increasing” is gyä, the second half of the word for Buddha in Tibetan, Sang-gyä. That is why Sangyä, “Buddha,” embodies the

purification of all negative tendencies and habits as well as the attainment of all beneficial qualities, which are then “vast,” gyä. Paying homage to Lord Buddha is honouring and revering the result of the path, the supreme state of perfection, which is enlightenment.

There is also the homage to the Bodhisattvas who are on the path, i.e., those progressing from the state of an ordinary being to that of perfection. Bodhisattvas have three qualities, as the connotation shows. The Tibetan term for the Sanskrit word bodhi has two

syllables, chang and chub. These two syllables mean, respectively, “cleansed” and “attained.” Just as the word sang in the Tibetan name for Buddha, Sangyä, cleansed means purified of the negative kleshas described above. A Bodhisattva has not cleansed all kleshas yet,

since he or she is still on the path, but gradually eliminates more and more while practicing the skilful methods of the path. The second Tibetan syllable for the Sanskrit word bodhi is chub, which means, “to obtain (the positive qualities).” A Bodhisattva unfolds more

and more qualities of being while he practices the stages of the path. In this way, a Bodhisattva develops qualities of purification as well as attainment.

The Tibetan word for the Sanskrit term sattva in Bodhisattva is sem-pa and means “a hero, a courageous and brave person.” A practitioner of the Buddhadharma indeed needs courage in order to eliminate his or her own faults that are impediments to the pure qualities of

being that everyone has. In the beginning, a practitioner needs confidence; he or she needs to know that it is possible to remove negative kleshas and to manifest values of worth. A student needs confidence that practicing the teachings Lord Buddha imparted will lead

to the beneficial results of purification and attainment, qualities a Buddha manifests freely and openly. A Changchubsempa, a Bodhisattva, sincerely and diligently works with and realizes these three values that beautify him or her: courage, purification, and

realization, and he or she never gives up.

In the past, texts that dealt with topics from the Abhidharma or higher knowledge began with homage to the Bodhisattva Manjushri, who embodies wisdom. The sword he carries symbolizes that he cuts the basic klesha of ignorance.

“I bow to the youthful, gentle and brilliant Manjushri.”

Texts written by Asanga in reliance upon instructions from Buddha Maitreya pay homage to the coming Buddha with the line:

“To the Guardian Maitreya we bow in supplication.”

The homage that the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, wrote in The Aspiration Prayer for Mahamudra begins with the Sanskrit words Namo Guru because the teachings of the Buddha and the commentaries written by scholars and Siddhas were translated from Sanskrit into Tibetan,

so it is to show that these teachings were not invented in Tibet but originated in India, the home of Lord Buddha and the great Siddhas. The homage in The Aspiration Prayer for Mahamudra is:

“Namo Guru

Lamas, Yidams and deities of the mandala.

Victorious Ones and your sons and daughters of the ten directions and three times,

Please hold us in your great loving-kindness

And bless our aspiration prayers that they may be perfectly fulfilled.”

Namo Guru means “homage to the Guru,” “homage to the teacher.” This is written because when one practices the Dharma, in particular meditation, one needs to rely upon a teacher for instructions. If one meditates without a guide, the meditation may be faulty. In the

same way as one needs a guide to show the way to a place one wishes to visit, one can end up where one didn’t want to go without one. With a guide, it is easier taking the right road and it is more likely that one will arrive at the destination one set out to reach. It

is the same with the practice of meditation. One needs a teacher because one has no experience. One needs someone who can instruct, “If you meditate in this way, then you will have that kind of experience, and when you have that kind of experience, this is what you

should do.” Trying to meditate without a guide may be all right but may go wrong. Even if everything goes well, there are different ways of practicing meditation. There might be a long way, there might be a short way, so one needs to have a teacher who has experience

in meditation and who can guide one in one’s practice. This is important for the practice of meditation in general but especially for Mahamudra and Dzogchen. That is why The Aspiration Prayer for Mahamudra begins with homage to the teacher.

Furthermore, the homage to all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, i.e., the Victorious Ones and their sons and daughters, is a request for their blessings, which must always be made. Some people think that they don’t need a blessing and that whatever they achieve is their own

making. But it isn’t like that. Others may think that a blessing gives them power and imparts an immediate transformation. But it is not like that either. One receives the blessings from the Guru in terms of positive karma, so that one will be able to gradually abandon

ill-will and increase the good, or that the one will be able to diminish the kleshas in one’s mind and enhance one’s good motivation as well as one’s love and compassion for others as one has for one’s own kin. One only gains wisdom through one’s own efforts as well as

through the blessings one receives, so there is a natural dependence. In The Aspiration Prayer, Rangjung Dorje also supplicated the Lamas and Yidams of the Transmission Lineage who abide in the splendorous mandala. One prays to them, too, because one has faith and

wishes to receive their blessings. It is a wish, and wishes come true if one has faith and sincerely tries.

A few lines from the homage Patrul Rinpoche wrote in The Words of My Perfect Teacher:

“Venerable teachers whose compassion is infinite and

Unconditional, I prostrate myself before you all.

Conquerors of the mind lineage, Vidhyadharas of the symbol lineage;

Most fortunate of ordinary beings who,

Guided by the enlightened ones, have attained the twofold goal –

Teachers of the three lineages, I prostrate myself before you.

In the expanse where all phenomena come to exhaustion, you

Encountered the wisdom of dharmakaya;

In the clear light of empty space you saw sambhogakaya Buddhafields appear;

To work for beings’ benefit you appeared to them in nirmanakaya form.

Omniscient Sovereign of Dharma, I prostrate myself before you .” (Patrul Rinpoche, Kungzang Lama’ i Shelung – The Words of My Perfect Teacher, Shambhala, Boston, 1998, page 3.

What is fruition of one’s efforts? Bringing appearances, which are generally experienced as imperfect, to a pure level. The view won through studying the scriptures means understanding that anything experienced is only relative. In truth, appearances have no real

existence, are like visions in a dream. Understanding the true essence of all things is experiencing their purity. It is not through reciting mantras or through receiving some substance, which one thinks possesses power, that impurity is transformed. It is through

understanding that appearances themselves are not imperfect, but that clinging to things as real generates and increases the confusion and suffering that the kleshas always entail.

What are impure and pure levels of being? Although things are in the absolute sense voidness or the pure nature, on the relative level things manifest in dependence upon one another; they originate one from the other. Impure levels of being are perceiving and believing

that things are real and exist independently, whereas the true nature of all things is emptiness. Appearances aren’t wrong; rather one’s way of relating to them - as though they were final and real - is mistaken. It is due to emptiness that things arise and cease again

and it is due to their unimpeded self-expression that they incessantly arise. On the relative level, things appear but in truth are non-existent, i.e., have no independent reality of their own. These two aspects only contradict each other as long as the interconnected

nature of all things is not understood. As a result, one perceives appearances and experiences and hides from one’s own limitations, because one cannot see that things appear while not existing in dependence, i.e., things seem to exist independently but don’t. The

right view attained through studying, contemplating, and meditating the Buddhadharma is realizing that relative appearances and their ultimate nature are not in opposition to each other but are the inseparability of emptiness and self-expression, i.e., appearances are

empty by nature, continuously manifest, and do so uninterruptedly. These are the three permanent aspects of lasting wisdom – the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya.

4. When Did Samsara Begin? When Will It End?

When did samsara begin? Always and ever, because it is beginningless. Following the homage to all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, Rangjung Dorje tells us in The Tathagatagarbhashastra:

“Though beginningless, it has an end.

It is pure by nature and has the quality of permanence.

It is unseen, because it is obscured by a beginningless covering,

like, for example, a golden statue that has been obscured.” That was taught (by the Buddha).

“The element of the beginningless time is the location of all phenomena.

Due to its existence, there are all beings and also the attainment of nirvana.” (That was taught by the Buddha.)

“All beings are Buddhas, but obscured by incidental stains.

When those have been removed, there is Buddhahood.” That is a quotation from Tantra.

Some students may think that the first sentence after the homage, “Though beginningless, it has an end,” is quite strange and they could argue that samsara must have a beginning somewhere and at some time. In fact, many people insist that anything and everything has a

beginning. But this is not so. Let us look at the example of a flower. Where did the flower originate? It came from a sprout, and the sprout grew from a seed. Where did the seed originate? It came from last year’s flower, and last year’s flower came from a seed that

was a product of a previous year’s flower – on and on, into the past. We clearly understand that there is no beginning and will never be found, no matter how hard people try. Similarly, the succession of lives in samsara has no beginning.

When will samsara end? Although never, Rangjung Dorje tells us, “it has an end.” This means that although there is no beginning, samsara has an end. How can this be? When one attains Buddhahood through practice, then samsara ends. Other texts say that samsara is

endless. How can that be? These statements seem to contradict each other. What they mean is that for an individual samsara is beginningless but will eventually end. Since there are so many living beings in samsara, it is, in fact, endless. This is the reason why

samsara does end and is endless at the same time – it is endless in that there are innumerable beings in myriad worlds entrenched too deeply in samsara to even sense that it is possible to experience relief.

In the second line of the shastra, Rangjung Dorje quoted the words of the Buddha from a sutra:

“It is pure by nature, and has the quality of permanence .”

This means that the Tathagatagarbha, the Buddha nature, has two qualities. Some people think that it is not faultless, but this is not so. It is immaculate and has no defect whatsoever. It is also permanent, i.e., it is continuously present, at all times, and therefore

has the quality of permanence.

Four qualities of the Buddha nature have been presented: It is beginningless, ends samsara, is by nature pure, and is permanent. One may wonder why it cannot be seen. The Karmapa tells us that

“It is unseen, because it is obscured by a beginningless covering .”

That is to say, it is covered and therefore cannot be seen, the fifth characteristic of the Tathagatagarbha, which is compared to a golden statue that has been concealed.

In the Uttaratantrashastra, Maitreyanatha presented the simile of someone possessing a piece of gold that fell from his hands and was lost in the rubbish around his feet. One day an impoverished man came along and built his shack on the mess. He lived there, atop the

lump of gold, destitute for food and clothes. The gold could not reveal itself, and the poor man could not see it hidden in the dirt under his hut. A clairvoyant could, and one day someone with such abilities walked by the shack. Out of compassion, he told the beggar

that he only needed to dig for the pure gold under his house and all his worries would stop. Yet, the poor man first needed to believe what the clairvoyant had told him before he started digging for the treasure he had been living on for such a long time. In the same

way, all living beings have the Buddha nature, which - like gold - is changeless. As long as we are in samsara, we cannot see it. The Buddha saw the Tathagatagarbha abiding within each and every one. Out of great compassion, he taught about the Buddha nature, showed

how to reveal it through practice, and proved that no one is forced to suffer samsara’s frustrations. Yet, we need to believe and trust him; then we are free to hear, contemplate, and practice the instructions in order to realize the true nature abiding way down

within. After unearthing the gold, samsara finally ends.

The Third Karmapa generously encourages us by quoting the Buddha:

“The element of the beginningless time is the location of all phenomena.

Due to its existence, there are all beings and also the attainment of nirvana.” (That was taught by the Buddha.)

He tells us that there is the element of beginningless time, the element that is the essence of the Tathagatas, and that it has been present within since time without beginning. It is the location of all magnificent qualities, too. It exists within all living beings,

without exception, and nobody is privileged before or above anyone else. Whoever practices the instructions that Lord Buddha gave, can attain the final result, nirvana, because

“All beings are Buddhas, but obscured by incidental stains.

When those have been removed, there is Buddhahood.” That is a quotation from Tantra.

Rangjung Dorje is sharing a quotation from the The Hevajra Tantra with us, that all beings are Buddhas, always and already, because they have the precious Buddha nature which is momentarily obscured by the kleshas, the incidental stains or negativities of the mind.

In the Madhyanathavibhanga - Distinguishing the Middle from the Extremes, Maitreyanatha gave three examples that show in which way the Buddha nature is obscured and can be purified again: Water is by nature pure but can be polluted by soil and dirt – it can be

cleansed. Gold is by nature pure but can be discoloured on the surface – it can sparkle again. The sky is by nature pure but can be obscured by clouds – it can and will be clear again.

Nagarjuna, the extraordinary Indian master of the first century A.D. who founded the Madhyamaka School, also dealt with this topic and presented the examples of the sun and moon. He tells us that they are by nature bright and clear but can be covered by a veil of

clouds or dust or they can be concealed from our sight through eclipses. Similarly, the Buddha nature is changeless and pure but can be obscured by the five kleshas (“the incidental stains” or “negativities of the mind”), which are summarized as five: craving, desire,

maliciousness, laziness, and doubt. These stains can be eliminated. When the sun and moon shine brightly again, they appear naturally and need not have been created anew. Just so in the text by Maitreyanatha, Distinguishing the Middle from the Extremes: Once the

pollution, incrustations, and clouds have been removed, the natural purity of water, gold, and the sky, respectively, appear naturally. Their purity is not created. Likewise, once the kleshas of the mind have been removed, the purity of the Buddha nature manifests

freely and radiantly. It is not created anew.

Rangjung Dorje stressed the importance of learning about the Buddha nature by offering quotations from the sutras and tantras, to enhance one’s trust and diligence towards experiencing and manifesting the true nature abiding within. Many students tell me that they

practice so hard but do not really know why. It is important to want to practice, and that is why Lord Buddha presented the teachings on the Tathagatagarbha. By having trust and confidence in our true nature and knowing that the experience of delusion, suffering, and

pain can end, we are inspired to make friends with ourselves and others by unveiling the Buddha nature that is always and already abiding within each and everyone.

5. Definitions of the Buddha Nature

We went through the introduction to The Tathagatagarbhashastra by Rangjung Dorje in the section, “When Did Samsara Begin? When Will It End?” It is a summary of the quotations on the Buddha nature from the sutras and tantra and introduces the contents of the shastra

that the Third Karmapa now offers in detail. The root text lists six definitions of the Buddha nature given in the sutras.

I pay homage to all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

“Though beginningless, it has an end.

It is pure by nature and has the quality of permanence.

It is unseen because it is obscured by a beginningless covering.

Like, for example, a golden statue that has been obscured.” That was taught (by the Buddha).

“The element of the beginningless time is the location of all phenomena.

Due to its existence, there are all beings and also the attainment of nirvana.” (That was taught by the Buddha.)

“Beginningless”

“Beginningless” means that there is nothing previous to it.

The “time” is that very instant.

It hasn’t come from somewhere else.

There is the element of beginningless time in all living beings, which is also the essence of the Tathagatas. It is the place from which all wonderful qualities of being arise and already exists within every living being without exception. This means that the one or

other person does not have a better chance of realizing his or her own true nature.

The word “beginningless” means that there is nothing previous to something, that nothing has gone before. If there is a beginning, then there wasn’t anything before. “Time” is therefore described in this verse as “that very instant,” i.e., time is the present mind in

this very instant. Its essence is emptiness and its nature is clarity. When the essence and nature have been realized, the ultimate is seen. One then realizes that the relative arises amid the vast expanse of the ultimate. The true nature of the mind is just that and

not outside conditioned existence.

Many texts speak about “four times.” The first three refer to the past, present, and future, which are relative truths because they are mental constructs, i.e., they are designated by the mind. For example, the present day is called “today,” the past day “yesterday” -

a negation of the word “today” - and the coming day “tomorrow,” but there is nothing definite or conclusive about these statements other than functionality. That is why there is beginningless-ness, the fourth dimension. Whoever practices the teachings given by Lord Buddha can achieve that recognition, since

“All beings are Buddhas, but obscured by incidental stains.

When those have been removed, there is Buddhahood.” That is a quotation from Tantra.

Rangjung Dorje continued by presenting the next five definitions of the Buddha nature according to the sutras. They are: element, phenomena, location, exists, and the end.

“Element”

The “element” has no creator, but is given this name because it retains its own characteristics.

The Tibetan term for “element” here is khams, the Sanskrit word is dhatu, a term frequently used for the Buddha nature in the sutras and predates the usage of the term Tathagatagarbha. So “element” refers to the beginningless Buddha nature, which is always and ever

present within all living beings. The definition of the term “element” in this context is therefore “the essence of the Tathagatas or Buddhas.” Thus the essence of the Buddhas is the element possessing all the magnificent qualities and characteristics of a Buddha. Who

created it? Nobody created it because it possesses its own qualities, i.e., the Buddha nature is replete with the knowledge of a Buddha, the love of a Buddha, as well as the power and qualities of a Buddha’s body, speech, and mind. These qualities are present within

each and everyone and can manifest abundantly when obstacles have been removed.

“Phenomena”

“Phenomena” are explained to be samsara and nirvana appearing as a duality.

This is named “the ground of the latencies of ignorance.”

The movement of mental events, correct thoughts and incorrect thoughts

are the cause of that arising (of samsara and nirvana).

The conditions for their causes are taught to be the alaya (the universal ground).

The translation of the Sanskrit term dharma is “phenomena,” chos in Tibetan. Two aspects of phenomena are presented in this treatise and are dealt with together: samsara and nirvana. As long as living beings are in a state of illusion they do not recognize the true nature of their own mind and experience basic frustration of being a separate self, i.e., they feel set apart from the world they apprehend as other than the self, which is samsara. When free from what causes that basic frustration, then they experience peace and

bliss, which is nirvana. Although both samsara and nirvana abound, they have no reality. As long as there is the delusion of samsara, there seem to be two distinct states, samsara set apart from nirvana. The basis for experiencing separation is called “the ground of

the latencies of ignorance.”

The sutras teach that everything is empty of inherent existence. In the Prajnaparamitasutra, for example, we read, “There are no eyes, no nose, no tongue, (…).” In the shastras we learn through logical reasoning why all phenomena are empty of an own existence. Great

masters like Chandrakirti offered proof why nothing has an inherent existence; Nagarjuna and Shantarakshita presented further arguments why the sutras are true. By studying their books we gain conviction and certainty in the fact that all phenomena are devoid of

inherent existence. These teachings show us that all things are empty, which is ultimate reality, and that things appear, which is relative reality. Emptiness does not mean that phenomena are a vacuum like space or non-existent when they do appear and exist.

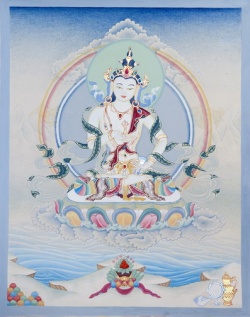

All things have a pure and an impure aspect, depending upon the view. The pure aspect of living beings is the Buddha nature, which is the clear and lucid power of awareness that everyone has. It is not a blank state. Maitreyanatha tells us in The Uttaratantrashastra

that the Buddha nature is the presence of clarity and omniscience. The Mahamudra instructions tell us that the Buddha nature is not beyond the realm of the mind that possesses awareness and conscientiousness. If one investigates where the mind is located – whether

inside or outside the body – one will never find it. Why? Because the mind as well as outer appearances have no reality. This does not mean to say that nothing happens or exists. Things exist just because the mind clearly perceives, understands, cognises, and knows.

When the mind is directed outwards, appearances can be recognized and known due to the clear aspect of the mind; one does experience appearances but fails to simultaneously recognize that the mind is empty. Mind’s essence is empty of an identity, its nature is clarity,

and its aspect is unceasing. It is due to the force of focusing on the clear and unceasing nature of the mind that its empty essence isn’t seen. Ignoring the mind’s essence is what Rangjung Dorje referred to when he wrote about the ground of the latencies of ignorance.

There is the ground of the latencies of ignorance, the ground amid which all delusory appearances arise.

In the Kagyu Tradition, the essence of the mind that is seen through practice is called “ordinary mind,” which means that nothing needs to be changed or manipulated in order to realize it; one merely looks at the mind’s true nature in order to see it. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche called recognition of the true nature of the mind “t-g-s,” an abbreviation for the Tibetan term tha-mal-gyi-shes-pa, which means “ordinary mind.” It is possible to directly see the nature of one’s own mind through the practice of Mahamudra. Without insight,

there is the ground with all the latencies of ignorance. All delusory appearances, all correct and incorrect thoughts, all conceptualisations arise within the ground. There is a very subtle movement, referred to as “winds,” arising from conceptualising, from thinking,

which Rangjung Dorje described in the line “The movement of mental events, correct thoughts and incorrect thoughts are the cause of that arising (of samsara and nirvana).”

Again, first there is the ground of ignorance and from that there is the subtle movement arising from conceptualisations, which in turn gives rise to the movements that stimulate the mind. When a practitioner realizes the ground, then there is the wisdom, the power,

and the great compassion of a Buddha. As long as somebody does not recognize the ground, there is delusion and all that follows. The ground of both delusion and liberation is called alaya, the Sanskrit term for “universal ground.” The Tibetan translation for alaya is

kun-gzhi, “basis of all.” The Third Karmapa wrote, “The conditions for their causes is taught to be the alaya (the universal ground).”

In classical Sanskrit, alaya means, “home, house or abode,” as in Himalaya, “the abode of snow.” It is from the root-word ali, “to come close to” or “to settle in.” While in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit it can mean “a habitation,” this term also has the meaning of “a

fundamental” or “ever-enduring basis.” The Sanskrit word therefore can also have the negative meaning of “attachment.”

Another description of the Buddha nature is “location,” the location for both samsara and nirvana.

“Location”

The “location” is the Buddha nature.

Incorrect conceptualisation is completely located within the mind’s purity.

Samsaric conceptualisations arise due to a deluded state of mind, and the basis of delusion is the Buddha nature, which is also called “the essence of the Jinas.” The Jinas are “the victorious ones.” The Tibetan is rgyal-ba’i-snying-po, “the essence of the Jinas,”

which is synonymous with de-gshegs-snying-po, “Tathagatagarbha.” The Sanskrit equivalent would be jinagarbha. In the section in this text, “When Did Samsara Begin? When Will It End?” the Third Karmapa explained that everything is located within the Tathagatagarbha. As

it is, there is the Buddha nature as well as incorrect conceptualisations. Where is the basis for incorrect conceptualisations? In the Buddha nature. There is no other condition for incorrect conceptualisations than the Buddha nature.

Changcha Rilpa’i Dorje was a Gelug scholar who gave meditation instructions and spoke about the time he was sitting on his mother’s lap as a child and always looked for her elsewhere, without realizing that she was so very near. His older brother told him, he turned

around and saw her. In the same way, we preside in the vast expanse of dharmata, the Sanskrit term for Tibetan chos-nyid, “the essence of reality, the completely pure nature that is ever present.” But we focus our attention on appearances that arise and seek truth

elsewhere, without realizing that it is ever so near. If we look inwards, we can see it. Even while deluded or when so many thoughts dash

through our mind, we are in the true nature – we cannot ever be anywhere else.

“Exists”

This purity that exists in that way exists, but is not seen due to ignorant conceptualisation.

The fifth description of the Buddha nature is that it exists in the present moment. One may wonder whether it undergoes any changes or transformations. No, it does not. It is pure and is always immaculate, but due to the delusions arising from the ground of ignorance

we are not able to see it. The example of gold was presented earlier, i.e., although gold may be buried under the earth for thousands of years, it never undergoes a change but always remains pure. The only reason why the gold is not seen is because the earth covers it.

Likewise, although the Buddha nature is always present, it never undergoes a change and always remains untouched. The only reason why the true nature is not seen is because it is obscured by the thoughts arising from ignorant conceptualisations, which is the nature of

samsara.

“The End”

Therefore, there is samsara.

If they (incorrect conceptualisations) are dispelled, there is nirvana, which is termed “the end.”

Rangjung Dorje tells us that samsara ends in the sixth definition of the Buddha nature. When conceptualisations arising out of samsara have been dispelled, then samsara ends. In The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, Je Gampopoa wrote that the Buddha nature is all-

pervasive. He compared it with oil concealed in a sesame seed, with butter in milk, with silver in silver-ore. Although present, one only wins the oil by grinding the sesame seed; one only gets butter by churning milk, and silver by melting ore. In the same way, wisdom

and compassion only emerge when incorrect conceptualisations have been dispelled.

As long as living beings remain ignorant of their true nature, understanding and wisdom are constrained. When samsaric involvement is eliminated, then the Buddha nature is directly seen and limitless wisdom and compassion emerge and manifest radiantly. This wisdom is

not mixed or tainted with pride, anger, and the other kleshas. The nature of knowledge and wisdom is love and great compassion for all living beings. Restricted love and compassion is compared to a mother who has no arms to save her child from drowning in the torrents

of a river that has swept it away. The mother would be helpless without the arms of wisdom, and the child would be lost. The incomparable love and compassion of a wondrous Buddha are not like that. A Buddha has abilities and strength. When the Buddha nature is directly

seen and realized, then there is unrestricted, limitless wisdom, compassion, and strength - the end of samsara.

6. How Does Samsara Arise?

Before dealing with the invaluable qualities of the Buddha nature presented in The Tathagatagarbha, it will be necessary to continue with the text in the sequence of its presentation. The first sections are entitled, “Homages in the Traditional Texts,” “Why Shastras

Were Written & Nine Categories of Shastras,” “When Did Samsara Begin?,” “When Will It End?,” and “What Are the Descriptions of the Buddha Nature?” The Third Karmapa continued by explaining how samsara arises. He divided this section into three parts: How samsara arises

through incorrect thoughts, how the root of delusion arises through attachment and aversion, and the remedy.

i. How samsara arises through incorrect thoughts

„Beginning“ and „end“ are dependent upon conceptualisation,

mental events that are like winds, that cause karma and kleshas to arise.

The (karma and kleshas) manifest the skandhas, dhatus, ayatanas

and all the phenomena of dualistic appearances.

Although there is no beginning or end to samsara, there seem to be a beginning and an end. One is separated from the truth when one thinks that there is a beginning and an end; these delusory thoughts give rise to the ground or latencies of ignorance. It is ignorance

that stimulates and gives rise to reactions, which are like airs or winds that are very subtle. It is due to the ground of ignorance that there is the subtle appearance of illusion concerning everything that arises, out of which the kleshas emerge. Klesha means “pain,

affliction and distress.” The Buddhist Sanskrit also means “impurity and defilements.” The Tibetan translation nyon-mongs means “physical or mental misery, distress, and misfortune.” As a standard term, it refers to various lists of ignorance, anger, envy, pride,

craving, etc. When the kleshas arise and reinforce the initial sensation, the chaotic forces that bring on frustration increase, too.

What is the basic illusion? Perceiving and conceiving that phenomena are separated from the self. It is because of attachment to “a self” and misinterpretation of “others” that pride, jealousy, maliciousness, and further inadequate mental activities spring up and grow.

The process increases if it is not recognized and pacified. Karma is accumulated in the process, both good and bad, due to mental activities that engage in trying to accomplish things to validate the insufficient feeling of “a self.” Karma literally means “action,”

though in other contexts it can also mean “duty and rite.” The Tibetan translation is läs, which means “actions.” Good karma is created through love and compassion, negative karma through ravaging emotions. The mental activities leave an imprint in the ground

consciousness, the alaya, where they are stored as latencies, which, in turn, stimulate and activate the five skandhas, the eighteen dhatus, and twelve ayatanas. We learned that all things that appear, all phenomena, are composed of parts and are therefore devoid of an

own identity. Nothing whatsoever is independent and therefore nothing has an own, inherent existence; all things are “a heap” of various components and factors, are therefore not singular and, in any case, not self-existent.

There are five skandhas of being. Skandha means “the (psycho-physical) aggregates.” In general Sanskrit this has many meanings, including “multitude, troop, aggregation, part, division, section, chapter.” In Buddhism, it refers to the five principal mental and physical

constituents of a being: form, sensation, identification, mental events, and consciousness. Form refers to any visible or tangible object. We think such things exist independently but they don’t; everything is a collection of many factors. The skandha of sensation

refers to any mental and physical irritation or feeling. The skandha of identification refers to perceiving and judging an irritation. The skandha of mental activities means reacting to what was identified. The skandha of consciousness is comprised of many factors and

is explained in great detail in the book, Transcending Ego: Distinguishing Consciousness from Wisdom. The Tibetan word for skandha is phung-po and literally means “a heap” but has the meaning of “aggregation.”

There are eighteen dhatus, “elements (of sensory perception),” khams in Tibetan, that give rise to the five skandhas. There are the six sense consciousnesses of sight, sound, smell, taste, tactility, and mind. These six consciousnesses arise due to the six sense

faculties and the six objects that can be perceived: sights, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile objects, and thoughts.

There are twelve ayatanas, “bases (of sensory perception).” The Sanskrit means “seat, abiding, place,” etymologically closely related to alaya. In Buddhist context, the sites, abodes, or supports of sensory experiences are the six sense faculties (the sixth being the

mental faculty) and their respective six objects. The Tibetan term is not a literal translation but is made up of the two syllables “birth” and “increase,” skye-ched, in reference to sensory experience. The inner bases of perception arise, develop, and increase.

Relatively speaking, the external objects are perceived by the internal minds, which arise and increase upon having perceived an object fit to be perceived by a respective consciousness.

Experiencing the dual as unitary, and vice versa, depends upon the skandhas, dhatus, and ayatanas, and all experiences are said to be like dreams. In a dream we see houses and places, we experience joy and fear, whereas those appearances - that the mind believes to be

real while dreaming - do not exist. Similarly, apprehending dualistically occurs in the mind, whereas the Buddha nature is non-differentiate. Logic and reasoning prove that all things arise from the mind. Yet we assume that what appears to the mind does not arise from

the mind and cling to the duality that there is something special about subjective experiences which distinguish it from objective things. Therefore, the “self” is in conflict with “other.” Earlier, we saw that nothing truly exists, that all things are by nature empty

of inherent existence. Let us take the hand as an example and seek its basis for imputation, its unitary reality. It is not hard understanding that the thumb is not the hand, that the flesh and bones are not the hand either. Does a hand exist independently of its

fragments and parts? No. It is easy seeing that there is no self-existing hand, no self-existing fingers, either, and no self-existing joints that do not consist of fragmented parts, too. Yet we speak of a unitary whole as if things were singular, unique objects,

independent, and free. In the same way, no object exists other than through the mind that identifies and designates the assembly of many parts as a whole. Therefore, all outer and inner appearances are mind, i.e., arise from the mind.

In meditation, we come to see that all external appearances are only mind. Then we meditate on the mind’s essence by looking at its nature, eventually discovering that one’s mind has no reality either, that it is empty of an own existence. Following this practice, we

meditate naturally present emptiness and discover that emptiness is not a void but that it is the fullness of perception that allows things to manifest and appear. It is called “supreme, naturally present, self-liberating emptiness.”

ii. How the root of delusion arises through attachment and aversion

Someone who strives for and discards these (appearances) is deluded.

What can be negated through rejecting your own projections?

What can be gained by acquiring your own projections?

Isn’t this belief in duality a fraud?

The glorious Third Karmapa explained how all things arise from the mind. If this is so, then all actions arising from attachment and aversion are illusory. Being in a state of delusion, appearances seem to be external and other than the mind. We hope that specific

appearances and experiences are beneficial and experience others with fear. We saw that actions arising from attachment and aversion are not only harmful but also wrong. When we realize that everything is an appearance of the mind, then there is nothing to get rid of

and nothing to be won.

iii. The remedy

Though this understanding is taught as a remedy, the understanding of non-duality is not truth.

It is the conception of non-conceptuality.

The understanding of emptiness gained through breaking down forms and so on,

isn’t it itself a delusion?

But it is taught so that attachment to things as real will cease.

It was taught that all dualistic appearances – all things perceived as “a self” and as “other than the self” – are experienced wrongly, that no appearance has a true and self-existing reality. Thinking that their essence is empty is a thought that has no reality

either, i.e., this thought is also a delusion.

Shantideva illustrated delusive thoughts: “One may dream of having a child and think it truly exists. Should it die in the dream, one would think it is dead. The thoughts of an existing as well as of a deceased child in a dream are both false since there never was a

child.” Likewise, thinking dualistic appearances exist is false and thinking that dualistic appearances do not exist is false, too. Contemplating that everything has no true reality is a remedy against clinging to what seems to be in discordance between appearances and

experiences. The Tibetan text actually addresses the realization directly by using the pronoun “you”:

Aren’t you yourself a delusion?

The great sage Saraha taught that clinging to things as real is stupid, but clinging to emptiness is even more foolish. Then why are these teachings presented? Why does The Prajnaparamitasutra teach, “There are no eyes, no ears, no (…)”? Why are the instructions about

the lack of independent existence taught? To counteract clinging to what appears as other than and foreign to the self.

Rangjung Dorje explained the difference between correct and incorrect thoughts profoundly in The Tathagatagarbhashastra, showed how delusions arise, and in which way they have no reality, whereby the thought that delusions have no reality is also an illusion. He

concluded this section with the lines:

There isn’t anything that is either real or false.

The wise have said that everything is like the moon’s reflection on water.

Allow me to repeat that a perceiver, the act of perceiving, and a perception have no true reality and that they are not false either. This may be very hard to understand and might seem contradictory. Therefore Rangjung Dorje shared the image of a moon’s reflection on

water with us. The reflection of the moon on the surface of a still lake is not the moon, but it would be wrong thinking that the reflection is not that of the moon. The “ordinary mind” does not cling to or channel delusory thoughts of chaotic forces and does not need

to be changed. Instead, the wise simply rest in the mind’s true nature and leave it “just as it is,” t-g-s, “ordinary,” while it is ever so brilliant.

7. Why Did Rangjung Dorje Write The Tathagatagarbhashastra?

The last section was a general introduction to the Buddha nature. Rangjung Dorje continued by presenting detailed descriptions.

The “ordinary mind” is called the dharmadhatu and the Buddha nature.

The enlightened cannot improve it. Unenlightened beings cannot corrupt it.

It is described by many names, but its meaning cannot be known through verbal expression.

The ordinary mind has many names. It is called “dharmadhatu” when the appearances of its empty essence are meant. It is called “the essence of the Sugatas, the Buddha nature, Tathagatagarbha” when its clear and all-knowing brilliance is meant. Dharmadhatu is a Sanskrit

term, the Tibetan is chos-kyi-dbyings.

Dharma means, “to hold,” “something held and prevented from falling.” The Tibetan equivalent, chos, has the connotation “to correct,” “to remedy,” “to alter,” which means that one corrects something by removing imperfections and by developing values of worth. Is an

elimination of imperfections and a development of qualities possible? Yes. Dhatu means “space” and refers to “the expanse of space.” It is truly possible to do so many things in the vast expanse of space; we can stand, walk, or fly. Everything we are able to do would

not be possible without all-inclusive space - dharmadhatu, the vast expanse that does not impede the elimination of shortcomings and the development of worth. The ordinary mind can work on eliminating faults and on developing positive qualities and that is why it is

called dharmadhatu, “the realm of dharmas, existents/phenomena” or “the realm of the truth, the Buddha’s teachings.”

The term Tathagatagarbha, “the Buddha nature,” “the essence of the Tathagatas,” “the essence of the Jinas” also defines the ordinary mind. Jina means “victorious one,” “a victor,” i.e., one is victorious over anything that harms and one is a victor over any source of

negativity and pain. It is the ordinary mind that can remove imperfections and that can develop positive qualities. Many other names are synonymous with the Mahamudra connotation “ordinary mind.” “Dharmakaya” refers to the experience of great bliss when suffering has

been overcome and “prajnaparamita” when confusion has been transcended. Although there are many names, they all define the Buddha nature.

Lord Buddha described the true nature of the mind by using many other terms, for example, “ultimate wisdom.” Although there are many names that describe the Buddha nature, it is ineffable. But when speaking about it, nobody can say that it exists or that it does not

exist since it cannot be identified or designated with words. How can this be? It is beyond thought, beyond conceptualisations, and can only be experienced directly through meditation.

The ordinary mind of an enlightened being and of a noble Bodhisattva on a high level of realisation does not improve or alter the Buddha nature in any way. The ordinary mind of a living being in samsara does not degrade, contaminate, or pollute it in any way. The

Buddha nature is changeless.

The five negative consequences that arise from having erroneous thoughts

There is a reason why the Third Gyalwa Karmapa wrote about the Buddha nature and why Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye the Great elucidated the shastra that discusses what had formerly only been introduced. These teachings help eliminate the five negative consequences that

arise from having erroneous ideas. What are they?

(1) Despondency, the first fault that can arise from having wrong thoughts about the Buddha nature, means losing hope. One may feel that one cannot eliminate the many shortcomings one has and does not believe that one can develop noble qualities of being. The teachings

on the Buddha nature dispel despondency by showing that one truly has the strength to work on reducing and eliminating any weaknesses or misgivings and that one has the ability to work on developing and increasing values inherent within.

(2) Hurting beings less fortunate than oneself is the second fault that can arise from having erroneous thoughts. If one denies that others have the Buddha nature, one might even think that there is nothing wrong with hurting those one considers low or inferior. In

some countries there is the caste-system and those born into what is considered a lower caste are treated badly or are not even offered a chance to participate in a society that deems itself fair and just. Some people are more learned than others and mistakenly believe

they will achieve more than those who are less learned. In some countries men are considered superior to women and even deprive them of humanitarian rights. The teachings on the Buddha nature tell us that all living beings have the Buddha nature and that nobody is

privileged, i.e., it is not the case that some have the true nature and others do not.

(3) Holding on to what is not true is the third fault that can arise from having erroneous ideas about the true. Thinking that only the elite or rich are endowed with the Tathagatagarbha and ignoring that everyone has it means fostering what is not true.

(4) Denying the Buddha nature is the fourth erroneous thought. One believes that the Buddha nature does not even exist, that goodness is a myth. These teachings are presented to dissever such pessimistic notions and negative ideas.

(5) Having pride of possessing a few qualities is the fifth wrong assumption. Someone may be proud of having developed a few qualities and then looks down on others as less advanced. However, if one knows that all living beings have the Buddha nature, then one sees

that nobody – not even oneself - is better than anyone else. This fault is also eradicated through these teachings.

Rangjung Dorje gave us these teachings so that we enter into sympathy and have empathy through the act of beneficent communication of awareness and conscientiousness.

8. Thirty-Two Unsurpassable Qualities of the Dharmakaya

Rangjung Dorje described the qualities of the Buddha nature in general and continued with the qualities of the unsurpassable dharmakaya in particular. He defined the virtuous qualities of the three kayas precisely in The Tathagatagarbhashastra.

Its unceasing manifestation (is taught) to have sixty-four qualities, though that is (just) a simplified description.

It is said that each of the sixty-four has millions (of qualities).

The Buddha nature unremittingly manifests sixty-four invaluable qualities, a condensed number in comparison to the real. Actually, each quality has millions. In general, the sixty-four are divided into those of the dharmakaya and those of the two rupakayas. Rangjung Dorje elaborated the thirty-two unsurpassable qualities of the dharmakaya.

The dharmakaya has thirty-two precious qualities, which are of the mind. They are defined as the ten strengths, the four types of fearlessness, and the eighteen distinct qualities of a Buddha only.

i. The ten strengths

There are the ten strengths: (1) the knowledge of appropriate and inappropriate actions; (2) the knowledge of the ripening of karma, (3) of natures, (4) aptitudes and (5) aspirations; (6) the knowledge of the destinations of all paths, (7) (the possession) of dhyana,

(8) divine sight, (9) the memory of previous lives, and (10) peace.

The ten strengths or powers are great abilities. They cannot be vanquished by anything. In The Uttaratantrashastra, Natha Maitreya likened them to an indestructible vajra in that they dispel one’s own and other’s ignorance and misunderstandings. That is the reason why

they are so powerful. The ten strengths arise from having developed Bodhicitta, from having held the Bodhicitta commitments, and from having become a Bodhisattva. Bodhicitta is the genuine and precious motivation to attain the state of a Buddha for the welfare of all

beings living in the vast expanse of space. It is divided into relative and absolute Bodhicitta. Relative Bodhicitta consists of the precepts of aspiration and the precepts of practice. Absolute Bodhicitta is identical with our true being, the Buddha nature. I have

explained the etymology of the term bodhi in the section on homages. Citta is “mind,” so Bodhicitta means “the precious mind of awakening.” Let us look at each of the ten strengths of the perfectly established mind of awakening.

(1) Knowledge of appropriate and inappropriate actions is the first strength, in which case a practitioner understands that certain causes bring on specific results. It is thorough knowledge of the interconnectedness between causes and results.

(2) Knowledge of the ripening of karma is the second strength, which means knowing the results that ripen from actions. It is perfect foresight of the ripening of karma.

Sometimes four types of karma are discussed: 1) Karma that will be seen, i.e., the result of an action will be experienced in the very same lifetime that the action was performed. 2) There is karma that will be experienced in the next lifetime, and 3) karma that will

be experienced after a number of lifetimes. 4) Furthermore, there is weak karma that need not be experienced, if and only if it has been purified through practice.

Sometimes two types of karma are explained: 1) Karma of initial impetus leads to rebirth in specific circumstances and situations and 2) karma of completion is all conditions of one’s present life. There are individuals who may have the initial karma for a good birth

and are born into a fortunate life as a result. But when karma of completion ripens, then they will experience trouble and pain. There are individuals who may have the initial karma for a bad birth, but if the karma of good completion sets in, then they will experience

an inferior rebirth, with enough food and good health though. There are other individuals who have both kinds of karma being bad; they will experience an unfortunate rebirth with much suffering and many difficulties. There are yet others who have both kinds of karma

being good; they will have a good rebirth and experience happiness and joy.

(3) Knowledge of natures refers to seeing beings’ makeup and constituents. A Buddha knows the hopes, fears, and interests that others have. When introducing someone to the truth of the teachings, a Buddha knows who will have faith and confidence in the path of

illumination and not only gives them a sense of direction but also affects their entire life through manifesting miraculous powers. He also knows who will have faith and confidence in the Dharma through hearing and learning the teachings. Other students may need to

actually see through examples of correct behaviour and discipline impressed upon them so that they win trust.

Because he knew the inclinations of human beings and because he knew what would be best for those who sought his advice, Buddha Shakyamuni sent those people ready for clearer insight to his noble pupil Shariputra, who instructed them in reasoning and valid cognition.

Lord Buddha sent those people attracted to miracles to his excellent pupil Maudgalputra, who performed miraculous deeds so that they were able to have trust. The Buddha sent those people sensitive to respectful behaviour to his perfect pupil Katyayana, sometimes

referred to by the name Katyaputra, who displayed discipline so that they would be encouraged and assured.

(4) Knowledge of aptitudes means that a Buddha recognizes the various capabilities of each and all in their toil to worthy themselves truthfully. For instance, some students may have trained in intellectualising but not be diligent; others may have much endeavour but

have little understanding. In general, students can have a preponderance for one or a combination of the five types of aptitudes: understanding, diligence, mindfulness, faith, and samadhi.

(5) Knowledge of aspirations: Some pupils may be keen on listening to the teachings, others intent on contemplating them. There are also students who prefer to meditate. Many people are interested in the Hinayana, others in the Mahayana. A Buddha knows which

instructions people can relate to and patiently teaches them, accordingly and adequately, so that they can determinedly work on the straight course in their quest for what is reliable and true.

(6) The knowledge of the destination of all paths means knowing the different yanas. For instance, if someone practices the Mahayana, then a Buddha knows which practice will benefit the most and which results that individual can achieve when working on self-mastery so

necessary in order to progress.

(7) The possession of dhyana, i.e., knowledge that possesses dhyana, the Sanskrit term for a “stable meditative state,” is the seventh strength. The Sanskrit term is the general word for “meditation,” both in its deepest sense and as contemplation. The Tibetan, bsam-

gtan, has the more general meaning of “stabilized thought,” emphasizing an undistracted state of mind. A Buddha knows the various states of meditation. He knows which klesha is overcome on each stage of practice, so that a mind poison is not precipitated and renewed.

(8) Divine sight means that a Buddha possesses the true and steady eye of wisdom that is capable of fathoming what is visible and invisible, the eye of wisdom that sees what is hidden and what will arise.

(9) The memory of previous lives: A Buddha remembers past lives, what they were, and what was achieved.

(10) Peace is the experience of cessation of kleshas, those pulling emotions that usually govern an unmanageable mind.

ii. The four types of fearlessness

Due to those (ten strengths), there are the four fearlessnesses: (1) teaching that one abides in enlightenment within all phenomena, (2) teaching the path, (3) teaching cessation, and (4) being beyond dispute.

The four types of fearlessness are compared to that of a courageous lion, the reason why the Buddha is often depicted seated on a lion’s throne. The lion’s throne symbolizes the presence of the straight, reasonable, and true that lead to courage of the four types of

fearlessness.

Fearlessness in benefiting oneself

(1) Teaching that one abides in enlightenment, within all phenomena, means not being afraid of looking at oneself, i.e., one is fearless about looking at and working on eliminating one’s own misgivings and ill-will and one is fearless about developing and increasing one

’s virtues and values of worth. This fearlessness is called “appreciation of the benefit of elimination and realization,” in Tibetan, chos-thams-cad-mngon-par-rdzog-par-byang-chub-pa-la-mi’-jigs-pa. According to Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye’s commentary, it means “

enlightenment within the expanse of phenomena or dharmas,” which is dharmadhatu. This term is however also interpreted as “the fearlessness of complete enlightenment in relation to all dharmas or to the knowledge of all dharmas.”

Fearlessness in benefiting others

(2) Teaching the path to others by not being balked by the dualism of selfishness and duty. The Tibetan is zag-pa-thams-cad-zad-par-mkhyen-pa-la-mi’-jigs-pa and translates as “fearlessness due to the knowledge of the cessation within oneself of all evil, misery, or

anything negative.”

(3) Teaching cessation means teaching others how to achieve the wonderful results. It is never the case that a Buddha is listless, perplexed, or thinks that all hardships were, are, or could be in vain. The second aspect of fearlessness in benefiting others is invoking

and guiding pupils not to give in to hindrances and impediments from day to day. The Tibetan is bar-du-gcod-pa’i-chos-rnam-gzhen-du-mi’-gyur-bar-nges-pa’i-lung-gsten-pa-la-mi’-jigs-pa, translated as “fearlessness in regards to the changeless, certain pronouncement to

others of what is an obstacle.”

(4) Being beyond dispute. Through setting an example and through reasoning, a Buddha can reliably teach his pupils how to pass through troubles that do arise while practicing the way. The Tibetan is ‘gyur-bar-nges-par-‘byung-ba’i-lam-de-bzhin-du-‘gyur-ba-la-mi’-jigs-pa

and means “fearlessness due to the definite results from the path.”

iii. The eighteen distinct qualities of a Buddha only

His Holiness the Third Karmapa wrote:

Due to those causes there are these eighteen (distinct) qualities: (1) no error, (2) no empty chatter, (3) no forgetfulness, (4) continuous meditation, (5) the absence of a variety of identifications, (6) the absence of an undiscriminating neutrality, (7) the

possession of an undeteriorating aspiration, (8) diligence, (9) mindfulness, (10) samadhi, (11) prajna, (12) the wisdom that sees complete liberation, (13)-(15) every action being preceded by wisdom, and (16)-(18) time being unable to obscure. If those thirty-two

(qualities) are possessed, there is the dharmakaya.

The eighteen distinct qualities of a Buddha only are said to be distinct because they are the marvellous and rare qualities that only a Buddha has; they are not those of Shravakas or Pratyekabuddhas. Maitreyanatha compared these unprecedented qualities with space in

The Uttaratantrashastra. As it is, there are the five elements of earth, water, fire, air, and space. Space is distinct because it has capacities that the other elements do not have. Likewise, a Buddha’s eighteen qualities are unprecedented and distinct because no one

else has them.