Bhûridatta Jâtaka Vatthu trans. from the Burmese by R. F. St. Andrew

- THIS translation has been made from a Burmese copy printed at the Hanthawati Press, Rangoon, but there is nothing to show whence the text was taken. I have also made use of a manuscript taken from the Mandalay Library, and now at the India Office. The gâthâ, which in many places seems to be imperfect, are not given in the shape of gâthâ in the Mandalay copy. In some cases the Burmese translation was redundant, and in others defective, so in translating them, though not a Pâli scholar, I have done my best to stick to the Pâli text, receiving some valuable assistance from Prof. Rhys Davids. The Jâtaka is No. 547 in the Ceylon List, and what is called one of the Greater Jâtaka, probably composed at a late date, as it refers to the Pa.n.dara Jâtaka, No. 521 [vol. v. p. 75, of Fausböll], which I have translated in a note from another Burmese source.

The object of this very remarkable Jâtaka is to set forth the general wickedness of Brahmans and the arguments in their favour given by Kâ.nâri.t.tha, who in a former birth had been a sacrificial Brahman, which arguments are refuted at length by the Bodhisat Bhûridatta. There are two points to which I would draw special attention, which may throw light on the date or period at which it was composed.

- 1st. In the twenty-first stanza of the first discourse (F. 157) there is a reference to certain practices in the country of Kamboja, which apparently has no connexion with what goes before.

- 2nd. The appellation of the snake-charmer-Alampâyano. A derivative of this word, viz. Alampay, is now used in Burmese to denote a person who is skilled in catching snakes (vide Judson's Dictionary), and it may be argued p. 78 that this word was taken from the name of this snake-charmer celebrated in Jâtaka-lore. I think, however, that there is evidence to show that it was not the man's proper name, but the name of the trade, for I find that the words used by the snake-charmer himself in relating the story of the Garu.la are, Alampâya.namantanâma "the charms of a snake-charmer."

- The word, therefore, I take it, has its derivation from Alam implying full, sufficient, and pâya drinking or having drunk. It may also be noted that the same word occurs in the Sudhammacari Stories, which I have given in Folk Lore Journal, vol. vii. part iv. p. 311, and that the Princess Sudhamma-cari is said to have been the daughter of Madda, a Râjâ of Kamboja.

- It is much to be regretted that books which appear to be published by the "Text-book Committee of Rangoon " are not more carefully edited. They are full of errors.

- P.S.--Since the above was written Professor Fausböll has had the very great kindness to favour me with a copy of his transcript of the Pâli verses of this Jâtaka. It would have been impossible without his aid, so graciously given, to restore the right reading of many of them.

- (From the Burmese.)

- CHAPTER I. (Nâgara.)

- One day, when the most excellent Buddha was residing in the Jêtavana Monastery, he came into the hall, and, sitting down, looked round at the Rahans assembled there. Seeing amongst them some laymen who were keeping the fast-day, he took them as the subject of his discourse, and said, "O devout laymen, ye do well in keeping the fast; but, in as much as ye have me to give you instruction, you must not think overmuch of your devoutness, for in past times there have been others who, though they had no teacher relinquished great wealth in order to keep the fast."

- p. 79

- At their request he then related the following birth-story:

- In times long past, when Brâhmadatta reigned in Bârâ.nasi, he appointed his eldest son to be Uparâjâ; but, seeing that he had accumulated much wealth and many adherents, he feared that he might become a source of danger to the throne, and said, "Dear son, I pray you depart into some other country, until I shall have passed away, when you can return and assume the royal estate, which is your inheritance." The Prince, obedient to his father's commands, left his country as a solitary

wanderer, and took up his abode in a hut in a valley near the river Yamunâ, where he assumed the garb of an ascetic, living on the fruits which he found in the forest. At that time a certain Nâga lady,[1] who had lost her husband, came up from Nâga land, and, seeing the Prince's footprints on the river shore, followed them till she came to the hut. The Prince being absent, in search of fruit, she entered, and, seeing his couch of dead leaves and other utensils, reasoned thus with herself:

"This hut belongs to a hermit: I will try him in order to find out whether he be a real ascetic, or only some person who is pretending to be one. If he be a real ascetic he will have no carnal desires and refuse to sleep on a couch that is adorned. If, however, he does recline on it, he will not be a real hermit, and will be willing to become my husband and dwell with me in this forest." She then went down to Nâga land, and, bringing thence some fairy flowers, spread them on the couch and withdrew.

- In the cool of the evening the Prince came back to his hut, and, seeing the flowers, exclaimed, "Who on earth can have done this?" He then made his supper and fell asleep upon the bed with sensations of delight. In the morning he got up, and, having swept out his cell, went again in search of fruits. When he was gone, the Nagini came again, and, seeing that the flowers were faded and crushed, said, "Evidently this is no hermit, but a man of ordinary passions." She then removed the old flowers and strewed the

- [1. The Pâli is matapatikâ nâgamâ.navikâ.

- p. 80 couches with fresh ones. The second night the Prince was again very much astonished but slept on the couch. In the morning he went out and concealed himself in the bushes near his hut to watch, and, on seeing the lovely Nagini, came out full of love for her, and asked her who she was. The lady replied, "My lord, I am a Nagini, and my husband is dead. Whence come you, my lord?" The

Prince told her that he was the son of the Râjâ of varanasi, and proposed that they should dwell together. The Nagini at once agreed, and caused a splendid fairy palace to spring up, in which they dwelt with all manner of delights. In due course the Nagini bore a son, whom they named Sâgara, because he was born near the sea; and when he was able to run, she had a daughter, whom they called Samuddajâ for the same reason.

- Not many years after this a hunter of varanasi came that way, and, recognizing the Prince, told him all that was going on. He told the Prince he would tell the Râjâ all about him, but, on reaching varanasi, found that the Râjâ was dead. On the seventh day after his decease the funeral took place, and then the nobles consulted, saying, "Sirs, a country that is kingless cannot ward off the thorns of strife, and as we know not where our Prince is, we are powerless. We had better make ready the

consecrated car[1] and send it forth in search of a king." Whilst they were thus deliberating, the hunter returned and reported his discovery. As soon as the nobles heard the news, they rewarded the hunter, and proceeded with a great retinue as the hunter directed them. On reaching the Prince's dwelling, they told the Prince that he must return with them and take up

the reins of government. Upon this the Prince went to his wife and said, "Lady, my father has departed this life for that of the Devas, and the nobles have come to ask me to assume the royal estate: let us both go and reign in Bârâ.nasi, which is twelve yojana in extent; you, my queen, will be the chief of 16,000 ladies." But

- [1. Consecrated chariot ([[phussaratho]), in which have been placed the four great elements (mahâbhûtâ), viz. earth, air, fire, water.]

- p. 81 she answered, "My lord Râjâ, I cannot, for I am endowed with a poison (or flame) which shows itself on the slightest feeling of irritation, and though I feel strongly that I ought to live with my husband, yet if I were to accompany him and anything were to arouse my anger, those who were the cause would be reduced to fine ashes: for this reason I cannot go with you." Next morning she

entreated him as follows: "My dear lord, since I cannot accompany you, and these children of ours, though Nâgas, are still to a certain extent human, be kind to them, if you really love me. Being of a race that lives in the waters, they are very tender, and cannot

bear the rays of the sun; cause therefore, I pray you, that they make vessels to hold water, in which they may be conveyed, and when they arrive at Bârâ.nasi have a tank made for them to sport in." Having thus spoken, she passed round him by the right hand and, after saluting him and embracing both the children, departed weeping to serpent-land.

- So the Râjâ, heavy at heart and with brimming eyes, went forth from their palace to where the nobles were waiting for him, and when they had poured over him the water of consecration, he directed them to prepare the vessels in which to carry his children. When

the vessels had been prepared, he directed that they should be placed on wheels and filled with water. In course of time they got to Bârâ.nasi, which was decorated for the occasion, and remained for seven days in a great pavilion surrounded by singers and dancers, whilst the nobles drank sweet liquors.[1] The Râjâ then ordered a lotus tank[2] to be made for the children to play in.

- One day, when they were letting the water into the tank, a tortoise got in by accident, and being unable to get out concealed himself there. When the Prince and Princess were swimming about, one day, it put its head above the water and looked at them. The children, seeing the tortoise, fled in terror to their father, and told him there was a

- 2. Pokkhara.nî.]

- p. 82 demon in the tank. The King summoned his attendants and ordered that the tortoise should be caught. When it was found and brought, and the children declared that it was the demon that had frightened them, he ordered that it should be punished.

- One nobleman suggested that it ought to be pounded in a mortar, another said that it ought to be boiled and eaten, another that it should be roasted; but one noble who was afraid of water, suggested that it should be thrown into a whirlpool in the river Yamunâ. On hearing this, the tortoise put out its head and said, "O Râjâ, what have I done? It would be a terrible punishment to throw me into a whirlpool, and I am ready to undergo any punishment rather than that."

- The King, being very angry, at once ordered that the tortoise should be thrown into the whirlpool, and when the sentence had been executed, the tortoise was sucked down by the current to serpent-land.

Just then a son of Dhatara.t.tha, the Nâga king, was sporting in the whirlpool, and seeing the tortoise, ordered it to be seized; whereupon the tortoise, who saw himself in a worse plight, cried out, "Friends, why do you, who are the servants of Dhatara.t.tha, treat me so roughly? I am an ambassador[1] from the Râjâ of Bârânasi, named Cittacû.la, and he has sent me to

inform your lord Dhatara.t.tha that he wishes to give him his daughter in marriage. Take me before your Râjâ." When the Nâga youths heard this, they took him before the Râjâ. But the Râjâ was displeased and said, "The Râjâ of Bârânasi ought not to have sent such an ugly fellow as this as his ambassador."

- The tortoise called out, "O Râjâ of the Nâgas, why do you say this? Ought an ambassador to be as tall as a palm tree?[2] Ambassadors, whether they be tall or short, are estimated on how they perform their duties. O Râjâ, my master the King of Bârâ.nasi has many ambassadors: on land he employs men and in the air

- [1. Dûto, an emissary.

- 2. Tâlo, Corypha.]

- p. 83 birds; I am Cittacû.la the tortoise, no common tortoise, but a nobleman and bosom friend of the Râjâ; do not revile me."

- Then the King of the Nâgas inquired on what business he had been sent, and the tortoise answered, "My lord, our master has made friends with all the kings who are on the face of the earth, but has not yet made an alliance with Dhatara.t.tha, the King of the Nâgas; he is, however, willing to give you his daughter Samuddajâ in marriage, and ordered me to come to your majesty and inform you. Do not delay, O Râjâ, but send some messengers with me to arrange the day for the wedding."

- Dhatara.t.tha, being pleased at this speech, summoned some of the Nâga youths, and directed them to go to Bârâ.nasi and arrange the wedding. So they went with the tortoise; but just before they got to Bârâ.nasi, the tortoise, seeing a pool of water handy, slipped into it and hid himself under the pretense of gathering lilies as a present. After waiting some time for the tortoise, they went on, and taking human form went into the presence of the Râjâ.

- The King asked them why they had come and they answered, "Your Majesty, we have been sent by Dhatara.t.tha, the King of the Nâgas, and we trust that your Majesty is in good health." The Râjâ then asked them what special business they had been sent on, and they said:

- 1. "Whatever treasure there is in Dhatara.t.tha's palace,

- Let all by thee be acquired; thy daughter give to the Râjâ."

- On the King hearing this, he was enraged, and answered:

- 2. "Not we a wedding with serpents contracted ever afore time,

- [1. Asa.myutta.m, according to B.M.S., means a bestial union.]

- p. 84

- Hearing this, the Nâga youths thought, "Of a truth this Râjâ belongs not to a race that is suitable to match with our King Dhatara.t.tha, and yet he sent his ambassador Cittacû.la to say he would give his daughter: we must display our power, and frighten this King of Bârâ.nasi, who has insulted our Râjâ." So they said:

- Should the serpent-king be angry, such as thou art would not live long."

- Varu.na's own son, Yamunâ,[3] dost thou purposely insult then?"

- The Râjâ of varanasi exclaimed:

- 5. "Indeed I despise not your king Dhatara.t.tha the famous,

- [2. Though iddhimo is given by Childers as supernaturally powerful, it is not so in Burmese translation.

- 3. Yamunâm, the Burmese translates as beneath Yamunâ, and not as a patronymic.]

- p. 85

- A princess she of Videhas, high-born lady Samuddajâ."

- On hearing this, the young Nâgas were very wroth and said, "Though we could now slay the King of varanasi, with the breath of our nostrils, since we are under our master's order to arrange a marriage and not commit destruction, it will not be right for us to do so; so we will go and report the matter to our Lord." They therefore returned to serpent-land, and on arrival

there the Serpent King questioned them, saying, "Dear sirs, how is it? Have you brought the Princess Samuddajâ?" The enraged messengers answered, "O Râjâ, you sent us to the King of varanasi without knowing the truth of the matter; if you are angry and desire to slay us, do it here in serpent-land. The Râjâ of Bârâ.nasi was puffed up with pride and reviled thee." Thereupon the Serpent King cried:

- 7. "Let the Kambals[1] and Assatars rise, the serpent hordes (quickly) inform,

varanasi let them invade, but let them not hurt anyone."

- When all the serpent tribes had assembled, they said, "O Râjâ, if we are to go to varanasi and slay no one, what are we to do?" And the Râjâ answered:

- 8. "Into the houses, the gardens, into the streets and the markets,

- Upon the trees, too, entwining, spreading yourselves in the gateways."

- [1. The Kambalo (a woollen cloth) and Assataro (mules) were Nâgâ tribes.]

- p. 86

- 9. "I too, white-shining all over, enormous, to this spreading city,

- 10. "The instant they heard his order, those serpents of various hue,

varanasi city pervade, but never a one do they injure."

- 11. "Into the houses, the gardens, into the streets and the markets,

- Upon the trees too they twisted, spreading themselves on the gates too."

- 12. "On these, when they saw them entwining, great was the wailing of women;

- Cried with their hands clasped in prayer, 'Thy daughter give to the Râjâ.'"[2]

- [1. So.n.dikate is translated in B. M. having their hoods expanded.

- 2. The above verses (10 to 13) are not given in the Rangoon edition, but are from Professor Fausböll's MS., and also in the Mandalay MS.]

- p. 87

- Thus they spread themselves all over the city of Bârâ.nasi in the houses, the streets, and water tanks, at midnight.

- And the four young Nâgas who had acted as ambassadors, twining their bodies round the legs of the couch on which the King was sleeping, spread out their hoods and showed their fangs and hissed loud enough to split his head. Dhatara.t.tha the Nâga King, too, overshadowed the whole city. Those who woke up in the night and stretched out their hands or feet felt nothing but hissing

serpents, and shrieked out "Alas! the serpents, the serpents." Some struck lights, and looking out saw the serpents writhing and twining themselves all over the gates and battlements and with one voice shrieked and wailed. So the whole city was in confusion, and when the day dawned, all the people, from the King downwards, were in a state of terror and cried out, "O great Lord of

the Nâgas, why do you thus torment us?" The serpents answered, "Your king sent an ambassador to our king promising his daughter in marriage, and afterward treated our ambassadors with contumely, acting deceitfully and treating our king as though he were naught but a brute beast; verily if your king gives not his daughter to our king, we will destroy this city and all its inhabitants."

- On hearing this, the people answered, "O great Nâgas, be not afraid but open a road for us to go to the palace and we will entreat our king." So the Nâgas allowed them to pass, and the people assembled at the door of the palace and wept with a great lamentation. The Queen, too, with all the ladies of the palace, cried out, "O Râjâ, give your daughter Samuddajâ to the King of the Nâgas." The four young Nâgas round the King's couch cried out, "Give, give!"[1]

- So the King of Bârâ.nasi was stricken with terror and shrieked out thrice, "I will give my daughter Samuddajâ to Dhatara.t.tha the king of the Nâgas."

- When he had uttered these words, all the Nâgas retired

- [1. This is the rough translation of verses 10 to 13.]

- p. 88 to a distance of three leagues from Bârâ.nasi and dwelt in a city which they had built for the purpose; they also sent suitable presents for the Princess. The Râjâ of Bârâ.nasi received the presents and informed the messengers that he would send his daughter in due state. He then sent for Samuddajâ and took her to an upper chamber in a turret of the palace, opened the window,

and said, "My darling daughter, look at that beautiful city. I am going to give you in marriage to the Râjâ of that city, where you will be a queen. It is not far from here, and when you call to mind your parents, it will be easy to return and see them." Having thus spoken persuasively, he caused her to wash her head, and when she had been decked in jewels and rich garments, he sent her in a carriage[1] with a retinue of nobles. The nobles of the Nâgas also came out to meet her with great

honor. They then entered the Nâga city and presented her to the King, who sent them back to Bârâ.nasi with rich presents. The King of the Nâgas placed the Princess in a splendid palace on a magnificent couch surrounded by Nâga damsels in human form, where she soon fell into a deep sleep.

- Then Dhatara.t.tha, accompanied by all his hosts, departed thence to serpent-land, and when the Princess woke up and saw all the Nâga palaces and gardens, which were like those in the land of the Devas, she inquired of her attendants; saying, "This country is very splendid and not like my own native land, whose country is it?" and they answered "Lady, it is the city of your lord and

husband, Dhatara.t.tha, the King of the Nâgas; it is not suitable for those who have not acquired merit. Since you have acquired merit, you have obtained this fairy dwelling-place and wealth." King Dhatara.t.tha issued a proclamation to be made by beat of drum throughout all serpent-land, saying, "Let no one dare show himself to Queen Samuddajâ in serpent form." So the Princess dwelt happily with Râjâ Dhatara.t.tha, unaware that she was not in the country of men.

- [1. Pa.ticchannayoggam, covered conveyance.]

- p. 89

- CHAPTER II. (Uposatha.)

Now in due course Queen Samuddajâ bore a son to Dhatara.t.tha, and as he was very beautiful, he was called Sudassana. Again, she bore another, who was named Datta. He was the Bodhisat. After this she bore Subhoga, and then a fourth, who was called Ari.t.tha. Up to that time Queen Samuddajâ did not know that she was in serpent-land; but one day some one said to the little Ari.t.tha, "Your mother is

not a Nâga, but a human being;" so he determined to put her to the test, and one day when at her breast he changed himself into serpent form and coiled his tail round his mother's instep. When the Queen saw this, she was terrified, and, shrieking, struck him to the earth with her hand, and one of her finger nails happening to injure his eye, he became blind in that

eye, and the blood ran out. Dhatara.t.tha, hearing the Queen cry out, asked what was the matter, and hearing what Prince Ari.t.tha had done, threatened to have him slain. But Queen Samuddajâ said, "O Râjâ, one of his eyes is put out, do not punish him further, be merciful I pray you." So the Râjâ, out of love for his Queen, pardoned him. From that day Queen Samuddajâ knew that she was in serpent-land, and her son Ari.t.tha was called Kâ.nâri.t.tha.[1]

- Now when the Prince was grown up, their father divided his country into five parts, and gave them each a division with a proper retinue. He kept one division for himself. Sudassana, Subhoga and Kâ.nâri.t.tha used to come once a month to see their father, but Datta came every fortnight, and if there was any difficult question, he would solve it.[2] When he went with his father to Virûpakkha,[3] be also solved any difficult questions that were asked. One day Virûpakkha went with all the Nâga hosts to Tâvâtimsa to do homage to Sakko, and a difficult question was mooted. When no one was able to solve it, the Bodhisat Datta

- [1. Kâ.no, one-eyed.

- p. 90 explained it, at which Sakko was delighted, and said, "Dear son, Datta, you are as full of wisdom as the earth is thick, from henceforth you shall be called Bhûri-datta."[1]

- From that day he remained in attendance on Sakko.[2] Seeing Sakko in his palace, called Vejayanta, surrounded by beautiful fairies dressed in goodly apparel and covered with jewels, he was desirous of becoming a Deva, and thought, "What advantage is there in being a raw-flesh[3] eating Nâga? I will return to serpent-land and keep the fast-days." So he returned to

serpent-land, and said, "Dear father and mother, I intend to keep the fast-days." They answered, "Dear son, do as you wish, but, if you keep them outside serpent-land, on the surface of the earth, there will be danger." The Bodhisat answered, "Good, I will keep them in a quiet garden in serpent-land."

- However, whilst thus engaged, the young Nâga girls surrounded him, playing on various instruments, and disturbed him; so he said, "I cannot keep the fast properly here, I will go to the country of men;" but, fearing that his parents might prevent him, he called his wives and said, "Ladies, I intend to go to the country of men and coiling myself round an ant hill at the foot of a banyan tree on

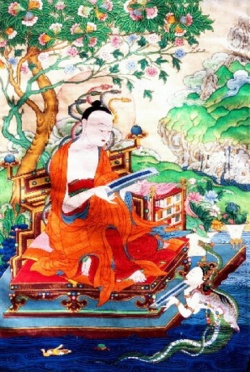

the banks of the Yamunâ, keep a fourfold fast: on the morning of the following day come with all your retinue and musicians, and conduct me back to serpent-land." Having thus instructed them, he went and coiled himself on the top of an ant hill and reflected thus, "If any one desires to take my skin, my sinews, my bone or my blood, let him do so." Then, making himself rigid like the log of a harrow, he kept the fast. When Âru.na sent forth his rays, the Nâga women came as directed and conducted him back to Nâga-land, and in this manner he fasted many times.

- 2. The Burmese form of Sakko is Sikrâ. The Sanskrit form Sakra, adapted to Burmese by changing a to i, which makes it the-kyâ, i.e. "He who knows and hears."

- 3. I find the Pâli word is ma.n.duka bhakkhena frog-eating. The mistake has occurred through the similarity of the Burmese words phâ a frog, and thâ flesh. So, green and raw being the same word, green-frog became raw-flesh.]

- p. 91

- CHAPTER III. (Nagarapavesana.)

- Now at that time there dwelt in a village near the gate of Bârâ.nasi a Brahman (named Nesâda), who, with his son Somadatta, used to get his living by killing deer. One day this Brahman, not being able to find even a lizard, said, "Dear son Somadatta, if we go home empty-handed, your mother will scold." Just then they came close to the place where the Bodhisat was fasting

and went down to the Yamunâ to drink. On coming up they saw the track of a deer, so the Brahman said to his son, "Somadatta, I see the footprints of a deer, stand still for a little and I will shoot it. Then taking his bow and arrows, he remained on the watch at the foot of a tree. The deer came down to drink and the Brahman shot at it, but it made off, leaving traces of its blood. The two hunters followed it up, and when they found it, the sun was just setting, and they arrived at the

banyan tree where the Bodhisat was fasting. They agreed that they would go no further that night, and, having hid away the carcase of the deer, climbed into the tree. In the morning the Brahman woke up, and just then the Nâga ladies had come to escort Bhûridatta back to serpent-land. Hearing the sound of their music, he tried to waken his son Somadatta, but being unable, he let him sleep and went alone, and going up to the Bodhisat said:[1]

- Who is this red-eyed, mighty, broad-chested one?

- Who these gold-bedeckt, well-adorned ones,

- These women, thy slaves, who stand in obeisance?"

- [1. The Pâli stanzas, if any, are wanting in the Rangoon edition, but are given split up in the Burmese MS.; as under by Professor Fausböll.]

- p. 92

- The Bodhisat answered:

- 16. "A Nâga I am, of great power, in glory surpassing,

- Should I bite with my poison in wrath, e'en prosperous townships (would be destroyed)."[2]

- 17. "Samuddajâ is my mother, Dhatara.t.tha too my father,

- Suddassana my younger brother, Bhûridatta 'tis they call me."

- After he had said this, he reflected, "This Brahman is a cruel old fellow; if he were to point me out to a snake-charmer, I should incur great danger. I will therefore carry him off to serpent-land and endow him with great wealth, and so be able to continue my fasts in security." He therefore said to the Brahman, "Come with me to serpent-land and see all its delights. I will give you great wealth." The Brahman answered, "My lord, I am not alone, but my son is up in the tree: if he may come too, I will go. After saying, "Call your son," the Bodhisat said:

- [1. Yakkho, a superhuman being.

- 2. The Burmese MS. supplies bhasmâ bhaveyya would become ashes. Tejo flame, power, is also translated poison.]

- p. 93

- 18. "This profound and ever-boiling pool, so dread, behold (I pray you),

- 'Tis my supernatural dwelling, deeper than a hundred fathoms."

- Yamunâ plunge into without fear, 'tis a realm of bliss and delight."

- He then bore away both father and son to serpent-land, and on arriving there they changed their human appearance to that of fairies. The Bodhisat gave them much riches and five hundred fairy wives. So the two Brahmans enjoyed great wealth and the Bodhisat was able to keep his fasts. Every half-moon he came to see his father and mother and preach the law; then he went to the Brahmans, and inquired after their health and wishes.

One day the old Brahman, after about a year had passed, felt unhappy, and wishing to return to the country of men, began to feel as if serpent-land were hell, and all the beautiful ornamented palaces like prisons, and the lovely Nâga girls like devils; so he determined to go and talk to Somadatta. On getting there he said, "Dear son, are you happy here?" Somadatta

replied, "Dear father, why should I not be happy? are you not happy too?" His father answered, "Dear son, it is long since I have seen your mother, brothers, and sisters, I am unhappy, let us go away." At first Somadatta refused; but as his father besought him, he at last consented. The old Brahman thought, "If I tell Bhûridatta that I am unhappy, he will

1. poriso. lit. a man, whose height represents a fathom.]

- p. 94 only heap more wealth on me. I must pretend to praise his wealth and splendour, and ask him why he relinquishes them to go and fast on earth. If he says that he fasts in order to go to Deva-land, I will say that we too must go back in order to get permission from our relatives to become ascetics: if I put it in this way, he will not be able to refuse, but will give me permission to return to earth." Shortly after this Bhûridatta came, and the old Brahman said:

- "Bhûridatta, in thy kingdom, this land complete in every way."[1]

- 21. "Where, ever through the live long year, this land of many tagra trees,

With golden fireflies o'erspread, is bright with new sprung grass."

- 22. "Delightful are its sacred places; pleasant is it with the sound of wild fowl.

- 23. "With well-wrought eight-faced posts, all made of precious stone.

Thy thousand-pillared palace stands, full of fair virgins, dazzling bright."

1. Verse 20 of Fausböll's gatha is not in the Mandalay MS. and does not seem to fit in anywhere, but is replaced by the half stanza:

- "Bhûridatta tava bhavane ayam mahi samâ samanta parito."]

- p. 95

- 24. "Thou hast a fairy palace, acquired by thy merit;

- So boundless, auspicious, agreeable, all else exceeding in bliss."

For thy wondrous power is even great as his."

- On hearing these stanzas Bhûridatta said,

- 26. "Friend Brahman, do not say this; my wealth is far less than that of Sakko; it is like comparing a mustard seed with Mount (Sinneru) Meru, my wealth being the mustard seed. We are but servants of Sakko, and ought not to be put in comparison with him."

On the fast day, doing penance, I lie coiled upon an ant hill."

- He and I, dead or alive, our nearest relatives know not."

- p. 96

- 29. "I let thee know, Bhûridatta, O noble scion of Kâsi,

- If thou wilt give us permission, once more we shall see our kinsfolk."

- To this the Bodhisat replied:

- 30. "Yea, 'tis indeed my desire that you should dwell in my presence;

- 31. "But if thou desirest not to dwell with my delights duly honoured,

- To thee I give free permission in safety to see thy kinsfolk."

- The Bodhisat then presented the Brahman with a ruby wishing ring that would grant all his desires, and said:

- 32. "He who bears this fairy ruby flocks and herds and sons possesses,

- The Brahman replied:

- p. 97

- The Bodhisat then said: "O Brahman, since you are determined to be an ascetic, so be it; but if at any time through inability to carry out your vows, you relinquish that life, come to me, without fear, and I will give you great wealth."

- "Bhûridatta, Prince of Nigas," said the Brahman, "your words are very pleasant: in the hour of need I will certainly come to you for help."

- The Bodhisat then summoned some Nâga youths and directed them to conduct the Brahman and his son back to the country of men; so they took them close to the city of Bârâ.nasi and left them. The Brahman then said to his son, "Dear Somadat, this is the spot where I killed the deer, and here I slew a wild boar;" and thus conversing about the old familiar haunts, they came to a pool of

water, in which they proceeded to bathe; and as soon as they went into the water, their fairy garments disappeared, and their old garments came in place of them, and their bows and arrows. Then Somadatta wept and said, "Father, to what misery we have returned after so much magnificence!" But the old Brahman replied, "Son, be not afraid, deer are not scarce in the forest, and we can still get our livelihood by killing them." Thus conversing they arrived at their home.

- When Somadatta's mother heard that her husband and son had arrived, she ran out to meet them, and, bringing them into the house, set food and drink before them. When he had eaten and drunk, he fell asleep, and then she said to her son, "Dear Somadat, you and your father have been absent for a long time, what city have you been residing in?" He said, "Dearest mother, Bhûridatta, the King of the Serpents, carried us both off to his country, but, though

- p. 98 we enjoyed great wealth and pleasure there, we were unhappy and have come back." "If that is true," said the Brahmaness, "have you brought any precious stones with you?" "No," said Somadat, "we have brought none." "Didn't the Serpent King give you a single thing?" asked the mother. "He offered my father a ruby ring, mother, but he would not take it; and I heard him tell the Serpent King that as soon as he got back to earth, he would turn hermit." "Ah!" said the Brahmaness, "he has forsaken his

wife and family all these long years, and I have had all the trouble of feeding the household, whilst he has been enjoying himself, and now he wants to become a hermit!" So in a furious passion she began to belabour her husband with the stirring stick, saying, "Heh! Brahman, what do you mean by coming back from Bhûridatta's country after refusing the wishing ring? You are going to be a hermit, are you? Very well, get out of my house sharp, will you!"

- The Brahman cried out, "Madam, do not get into such a passion; deer are not scarce in the forest. I will practise my calling as a hunter, and support you and your family." He then went off with his son into the forest.

- Now at that time a Garu.la was perched on the top of a silk cotton tree in a forest on the shore of the southern ocean, flapping its wings, by which means it divided the waters and seized a Nâga that was below. In those days the Garu.las did not know the proper way of seizing a Nâga, and used to seize them by the head; but afterwards, through the advice of a hermit, which is related in the Pa.n.dara Jâtaka,[1] they learnt to seize

- [1. The Pa.n.dara Jâtaka is to be found in Jâtaka, vol. v. p. 75, and the Burmese version from the Ma.niratanapon is attached to this as a note.

- In the country of Bârâ.nasi, when Brahmadat was king, 500 sailors were wrecked in the sea, and, by the force of the wind, one of them was carried to Karampira harbour. On account of his emaciated body, people said, "This ascetic is a person of small requirements," so they kept him. Thinking that he was now well off, and to keep up his character, when they offered him garments

he declined them. The people, thinking it was impossihle to find a more abstemious man, had a great regard for him and built him a cell, and he was known far and wide as the "Naked one of Karampira" (Karampira acelaka). A prince of the Nâgas and a prince of the Garu.las used to come and worship him, and one day, when so engaged, the Garu.la said, "We Garu.las when catching Nâgas are often destroyed by drowning, there must be some secret cause for this; when the Nâga comes, ask him the reason and let me know." The ascetic agreed, and when the Nâga came, he questioned him; and the Nâga said, "If I were to tell

this, all the future generations of Nâgas would be destroyed; but if you will promise not to reveal it, I will tell you." The ascetic promised, saying, "If I do, may my head be split in seven!" The Nâga then said, "When the Garu.las are going to swoop, we make ourselves a thousand cubits long and swallow a great rock and then show fight with our heads, so when the Garu.las seize our heads they cannot lift us and get drowned; but if the Garu.las seized us by the tail and held us upside down, we should vomit the rock." The

hermit, however, did not keep his promise, but told the Garu.la. The Garu.la, therefore, went and seized the Nâga, and whilst he was being carried off, he told the Garu.la how he had been deceived. The Garu.la took pity on him, and telling him that it is always best to keep secrets, let him go. The Nâga then wished that the punishment of oath-breaking should befall the hermit, and immediately his head split into seven pieces and he went to Avici.]

- p. 99 them by the tail. This Garu.la, however, not knowing the right way, seized this Nâga by the head, and carried it off wriggling to the Himavanta forest. There was also at that time in the country of Kâsi an ascetic Brahman, who dwelt occasionally in a cell in the Himavanta, near which there was a great banyan tree, and as this hermit was sitting at the foot of the tree, the Garu.la flew past with the Nâga. The Nâga twisted its tail round the branches of the banyan tree, but the strength

of the Garu.la was such that it carried off the tree with the Nâga, without being aware that it had done so. The Garu.la, perched in a tree, devoured the Nâga's entrails, and threw the body into the sea, whereupon the banyan tree fell with a crash. The Garu.la looked round to see what it was, and thought, "Why, this must have been the banyan tree, that grew by the hermit's cell. I must go and find out whether he is angry with me for what has been done." So he flew down to the hermit's cell, and, having taken up a

reverent attitude, said, "O hermit, what is this level spot!" The hermit answered, "O Garu.la, my supporter, a Garu.la came flying by here with a Nâga, and as he passed the Nâga twisted its tail in the banyan tree and it was carried away." "Is the Garu.la to be blamed, O hermit?" "No, Garu.la, the Nâga did it in self-defence; and is not to be blamed." "Reverend Sir, I am

that Garu.la, and I am much gratified at the manner in which you have replied to my questions; I know a charm that will keep p. 100 off all serpents, and will impart it to you for your kindness." The hermit answered, "I have no need for snake-charms, go in peace." But the Garu.la insisted and taught him the charm.

- There was also at this time a poor Brahman in Bârâ.nasi who was sore pressed by his creditors, so he went out into the forest, saying, "It is better that I should die there than continuing to live in this wretched manner." In due course he came to this hermit's cell, and served the hermit in many ways, and in return the hermit imparted to him the snake-charm, which had been taught him by

the Garu.la, and also gave him some of the medicine which had been given him. The poor Brahman, having now got a means of livelihood, stayed a day or two longer, and then saying he had got the rheumatism, and wanted to get medicine for it, took his departure. After a short time he arrived at the banks of the Yamunâ, and went along the road repeating his charm. Just then a thousand of

Bhûridatta's female attendants came, bringing with them the great wishing ruby, and, whilst they disported in the water, placed it on a sand-bank, to give forth its light during the watches of the night. At dawn they put on their ornaments, and, surrounding the great ruby, displayed their splendour. As the Brahman came up, the Nâgas heard him reciting his charm, and, thinking he was a Garu.la, fled, leaving the ruby, on seeing which the Brahman was delighted and carried it off.

- Just then the Brahman, Nesâda, and his son, Somadatta, came out of the forest, and, seeing the Brahman carrying the ruby, he said, "Dear Somadat, is not this the ruby that the Prince Bhûridat offered us?" "Yes, father, it is the very same." "Then (said Nesâda) we will get it by stratagem, for he does not know its value." Somadatta answered, "Father, when Prince Bhûridatta offered it to you, you refused it; why do you want it now? Perhaps the Brahman will be too sharp for you. Do not speak to to him, but keep still." But Nesâda answered, "That may be, but just see how we shall both try to get round one another."

- p. 101

- He then said to the snake-charmer:

- Stone so perfect in appearance, tell me where you found this jewel."

- To which the snake-charmer replied:

- 39. "By a thousand red-eyed damsels guarded well on every quarter,

- Then said Nesâda, "O snake-charmer, the nature of rubies is such that if one looks after and honours them, they bring great luck to their owners; but if they are not well looked after, they bring harm. You are not the sort of person to carry about a ruby, sell it me for a hundred pieces of gold. I know how to treat it." (Nesâda had not a hundred pieces of gold, but he thought that if he once got it into his possession, he would soon get the hundred pieces.)

- 40. "Well looked after this stone, constantly honoured and revered, will accomplish every desire."

- 41. "To the possessor who neglects it, it will bring destruction."

- p. 102

- 42. "Thou unfortunate one art not worthy to carry this fairy stone, take a hundred gold pieces[1] and give me the ruby."

- The snake-charmer, however, answered:

- 'Tis a stone of wondrous virtue; no, it can't be bought, my ruby."

- Nesâda.

- 44. "Since, this ruby's not for barter, for aught else nor e'en for jewels;

- Alampâyano.

- To that one I'll give this jewel, with its rays so brightly shining."

- Nesâda.

- Dos't thou seek the longed-for Nâgas?"

- [1. Nikkham = 5 snva.n.nas = 25 dhara.nas = 250 phalas.

- 2. Supanno, the King of Garu.las.

- p. 103

- Alampâyano.

- 47. "No, I am not of birds[1] the ruler; never have I seen Garu.lo."

- Snake-poison doctor,[2] Brahman, they call me.

- Nesâda.

- 48. "What, I pray, is this thy power? what this art but known to thee?

- On what is it thou reliest that thou fearest not the serpent?"

- Alampâyano.

- Supanno, who rules o'er Kâsi[3]

- To this Kâsi man Supanno } taught this serpent-poison queller."

- [1. Dvijo twice born. A Brahman; a bird, which is born twice, first as an egg, and then from the egg.

- 2. The Mandalay MS. reads, âsivisena vittovivecako the dissipator of snakes' poison, which the Rangoon copy translates: "No Brahman, I am no Garu.la; in fact, I have never seen one, but am merely a poor snake-charmer who can allay the power of serpents."

- p. 104

- Reverently I fed and tended, night and day, without remission."

- 51. "He, thus served and honoured by me, both as servant and disciple,

- Nesâda then said to his son:

- The with-difficulty-found good, let us willing not relinquish."

- 54. "To you who arrived at his dwelling, O Brâhman, he gave nought but honour

- 'Gainst one who has thus been so gracious, why foolish wish to transgress?"

- p. 105

- 55. "E'en though thou desirest riches, respectfully treat Bhûridatta,

- To him then, going, thy wishes relate, and he'll give thee great wealth."

- Nesâda.

- 56. "The food that has come to your hand or your cup 'tis better to eat,

- The good that is laid at our feet, Somadatta, let us not lose."

- 58. "If in truth thou long'st for riches, go and reverence Bhûridatta;

- Well I know our evil doings will e'er long bring retribution."

- Nesâda.

- 59. "By performing sacrifices Brahmans cleanse themselves from evil,

- [1. The above is Fausböll's reading, but the Mandalay MS. has Mahi yâma pi virati, the earth and Yâma swallow.

- 2. 60 and 61 not given as gâthâ, but as above.]

- p. 106

- Then said Somadatta; "I will flee from thee, for I cannot remain with one who can do such evil deeds." So with a mighty cry he called on the Devas to witness that he could no longer remain with so base a father, and fled into the Himavanta forest, where he became a hermit and attained so much merit that he at last migrated to the Brahma heavens.

- Nesâda, thinking that his son had gone home, and that the snake-charmer was heavy of heart, said, "Friend snake-charmer, do not be unhappy, I will show you Bhûridatta the Nâga Prince." He then took him to where Bhûridatta was fasting, and when they got there, and saw him on the top of the ant hill, he stopped and said, pointing at him:

- Like fire-flies sparklingly brilliant is his head with its glowing eyes."

- 63. "Like well-carded cotton, I ween, his body is seen there,

: On an ant hill's summit he sleeps, him do thou seize then, O Brahman."

- Hearing this, Bhûridatta opened his eyes, and beholding Nesâda, thought, "That man wishes to do me a mischief whilst I am fasting. I took both him and his son to Nâga-land, and when they wished to depart, I offered them precious stones, but he would not take them, and now he has come with this snake-charmer. If I were to show my wrath to this Brahman, who is so treacherous to his friends, my

- [1. The Mandalay MS. has eso kâyo paddissati his body is to be seen; Fausböll, eso kayassa dissati.]

- p. 107 fasting would be of no avail. It is better to pursue this course of religious duties than to be irritated. If this serpent-charmer wishes to cut me in twain, let him do so: if he desires to cook me, he may do so; or toast me on a spit, he may do so: I will not be angry. If I were to look at those two, in my wrath, they would melt like cakes of honey; but I will not, and if they smite me, yet will I not be enraged." Then, closing his eyes in fixed determination, he withdrew his head into his coils and lay motionless.

- Then said Nesâda again, "Snake-charmer, seize this serpent and give me the ruby." Whereupon the snake-charmer in delight threw him the ruby, saying, "Take it, brother." But the ruby slipped through his fingers and falling to the earth, disappeared, going back to serpent-land. When Nesâda saw that the ruby was gone and his son too, and that he had also lost his friend Bhûridatta, he said, "Alas! I have greatly erred in not listening to the advice of my son," and he wept bitterly.[1]

- The snake-charmer then, having smeared himself all over with ointment to protect him, and having recited his charm, approached the Bodhisat, and seizing him by the tail, grasped him firmly by the head. He then opened his mouth, and having put drugs into it, spat into it.

- The Bodhisat, however, for fear that he might lose the merit of his religious duties, remained unangered and with closed eyes.

- Then the snake-charmer held him by the tail,and shaking his head downwards, caused him to vomit, and then laying him at full length, kneaded him like a piece of leather.

- [1. The Mandalay MS. does not give S. 64.]

- p. 108 Then again taking him by the tail he banged him up and down, like one who washes clothes. Still, though the Bodhisat underwent all this misery, he showed no anger. The snake-charmer having thus taken all the strength out of him, and woven a basket of canes, put him into it. As the body of the Nâga Prince was larger than the basket, the snake-charmer pressed him into it

with his heel, and having thus forced him into it, carried him off to the neighbouring village, where he summoned the people to see a performance. When the people were assembled, he cried out, "Come forth, prince of serpents." The Bodhisat, thinking that it would be better to come out and dance, so that the Brahman might get a considerable amount of money, and then release him,

came forth and did all that the snake-charmer ordered him to do. When the people saw him go through this performance, there was not a dry eye amongst them, and they threw their gold and silver ornaments to the Brahman: and in that village alone he got property worth a thousand pieces.

- Now it happened that when the snake-charmer caught Bhûridatta, he had determined to let him go again, after he had accumulated a thousand pieces of silver; but being a covetous man, he broke this good intention, and having made a handsome decorated cage and purchased a comfortable carriage, he went from town to town, surrounded by many followers, and at last arrived at the city of Bârâ.nasi. He

fed Bhûridatta on parched corn and honey, and caught frogs for him, but the Bodhisat refused to eat, seeing that he would not be released; however, the snake-charmer made him dance in all the quarters of the city. On the 15th day of the month, which was a holiday, he obtained permission to give a performance before the Râjâ, and tiers of seats were erected on the plain before the palace.

- Now on the day that Bhûridatta was caught, his mother, Samuddajâ, dreamt that "A man, with red eyes, cut off her right arm with a sword and carried it away streaming with blood." She sprang up in terror, feeling for her arm, p. 109 but finding it was there, knew that it was only a dream. Then she thought this evil dream must portend some great calamity to her or her

husband, and said, "Verily, I am in great fear for my son Bhûridatta, for all the others are in Nâga-land, but he has gone to fast in the country of men: I fear that he has been seized by a snake-charmer, or a Garu.la." On the 15th day after this dream she thought. "It is more than half a month since Bhûridatta came here; I feel certain some evil has befallen him." So she began to

weep, and her heart dried up with grief. She was always gazing on the road expecting to see him come. After a month had expired her eldest son, Sudassana, came to see her, but on account of her grief she said nothing to him. So Sudassana, seeing how different his reception was, said:

- 65. "Me though thou seest approaching and though thou hast other delights,

- Thy senses are not overjoyed; overcast and dark is thy face."

- 66. "The lotus flower plucked by one's hand lies crushed and withered and faded;

- Dark is thy face (O my mother), though thou seest me in this wise."

- p. 110

- "Let us then go to the home of my dear son Bhûridatta and see how it fares with thy brother, who is keeping the fast." So they set out together with a large retinue.[1]

- Now when Bhûridatta's wives were unable to find him at his place on the ant hill, they were not alarmed, but thought he had probably gone to see his mother, and being on the way to inquire, they met her on the road, and told her that he had been absent for more than half a moon, and thought he had gone to her. When they found this was not the case, they fell at her feet weeping. His mother joining in their lamentations, went with them up into his palace, saying:

- 75. "As a bird bereft of its young, when it sees its empty dwelling,

- Long time shall I burn with sorrow, Bhûridatta not beholding."[2]

- 77. "Long time shall I burn with sorrow, Bhûridatta not beholding.

- Long time shall I burn with sorrow, Bhûridatta not beholding."

- [1. Stanzas 70, 71, 72, 73, and 74 are not given as such in the Rangoon edition, but partially translated as above.

- 2. S. 76 is not given in the Rangoon edition.]

- p. 111

- 79. "Inwardly the blacksmith's furnace smoulders, outward signs it shows not;

- So does inward grief consume me when I see not Bhûridatta."

- Prone his children, prone his women, in the house of Bhûridatta."[1]

- As Bhoga and Ari.t.tha, the younger brethren, were coming to pay their respects to their parents, they heard the sound of the wailing, and came to Bhûridatta's palace to comfort their mother, saying, "Mother, be comforted; no mortal can escape the law of death and destruction."

- Their mother replied, "Dear sons, I know that all that exists is destroyed, but, nevertheless, I am terribly disturbed at not seeing Bhûridatta. Dear Sudassana, if I see not my son Bhûridatta, I shall die this very night."

- The Princes answered, "Dear mother, be not afraid, we will go into the forest, the mountains, the caves, the villages, towns, cities, and everywhere in search of Bhûridatta. You shall see him within seven days."

- Sudassana said, "If we search together, the search will be long; we will separate and search in different directions. One of us will go to the Deva-land, one to Himavanta, and one to the country of men." As Kâ.nâri.t.tha was fierce, he thought it best not to send him amongst men, for he might reduce everything to ashes; so he said, "Brother Ari.t.tha, do you go to Deva-land, and as the Devas are desirous of hearing the law, without fail bring him thence."

- p. 112

- He then directed Sûbhoga to go to Himavanta, saying that he himself would go to the land of men. Then he thought, "If I go as a youth, men will think nought of me; but if I go as a hermit, they will respect me, for the children of men love hermits." Thereupon he took the form of a hermit and took leave of his mother.

- Now Bhûridatta had a cousin[1] who was very fond of him, named Ajamukhî.[2] She loved him better than all her other cousins, and seeing Sudassana about to depart, she said, "Cousin, I am very sad, let me accompany you in your search for Bhûridatta!" He answered, "Child, I am going disguised as a hermit, and it will not do for a woman to go with me." Then she said, "I will take the form of a frog and go in your hair-knot." On his agreeing to this Ajamukhî took the form of a frog, and stowed herself away in Sudassana's top-knot.

- Sudassana then caused Bhûridatta's wives to show him the ant hill, and when he saw traces of blood, and the spot where the snake-charmer had woven the cage of cane and bamboo, he said, "Without doubt my brother has been taken by a snake-charmer,

who is ill-treating him." So in great sorrow he tracked the bloodstains and footprints until he came to the village where the first performance was held. On questioning the villagers, as to whether any snake-charmer had been there, he was told that one had been there about a month previously. On asking if he had taken any money, they said, "O yes, he is quite a rich man, for he got about a thousand pieces of

silver here." So they went on making inquiries until they came to the King's palace. Just at this moment the snake-charmer, who had bathed and dressed himself, had taken up his cage and gone to the gate of the palace, and the people of the city were assembled to see the performance. The snake-charmer spread out a magnificent carpet, placed his cage open upon it, and playing on his drum, cried out, "Come forth, great

- [1. Mother's sister's daughter.

- p. 113 Nâga." Sudassana, standing in the crowd, saw the serpent-prince raise his head and gaze at the crowd. Now there are two occasions on which Nâgas are wont to gaze; first, when they are in fear of Garu.las: second, when they see a friend.

- The Bodhisat, seeing his brother in the crowd disguised as a hermit, came out of the cage with his eyes streaming with tears, and went straight towards his brother. The people stood aside with fear, but Sudassana kept his place. The serpent, laying his head on Sudassana's instep, wept. Sudassana also wept. Then Bhûridatta returned to his cage.[1] The snake-charmer, fearing that the snake had bitten the hermit, came towards him, saying in verse:

- Alampâyano.

- 87. "The snake released from my hand, dear hermit,[2] has rested on your foot. Did it bite you? be not afraid; be happy."

- 88. "Fear not, snake-charmer, thy serpent could do me no harm; nowhere is there a snake-charmer more powerful than I am."

- Snake-charmer.

- 89. "Who, I pray, is this, who in the disguise of a Brahman has entered this assembly and thus taunts me? Fool that he is. Listen to me, O assembly."

- p. 114

- 90. "Snake-charmer, set thy serpent against me, and I will back my little frog; let there be thereon a wager of 5000 pieces."

- Snake Charmer.

- 91. "Youth, I am rich, but thou art poor; how shall I get my money from thee? If I lay this wager, who can you give as surety? What the stakes?"

- 92. "The stakes too I have and my surety is of this sort. Let our stakes be therefore five thousand pieces of silver.

- Then stepping fearlessly into the king's palace, Sudassana said,

- 93. "O mighty Râjâ may thy kingdom and wealth increase. Listen to me. I am in want of 5000 pieces of silver, and wish thee to stand surety for me."

- 94. "As a paternal debt, or one of your own making, why dost thou thus demand of me so much wealth, O Brahman?"

- [1. Prof. Fausböll gives âlamba for alampâyana. If this be correct, the derivation would probably be from â.lambaro a little drum, which may have had a root âdam; or a word for this kind of drum in the Hill tracts of Aracan is ºatam, and snake-charming originated, no doubt, amongst the aboriginal inhabitants of India.]

- p. 115

- 95. "Alambano with his serpent desires to fight me. I, with my little frog, will bite (fight) the Brahman."

- 96. "Do thou in order to see, maharâjâ, protector of the kingdom, now with thy assembled nobles surrounded, come forth to the fight."

- Now, when the snake-charmer saw the Râjâ coming with the hermit, he thought, "Of a truth this is no ordinary hermit, he is in all probability the Râjâ's teacher." So he came up to Sudassana, and said:

- 97. "O youth, I desired not to show you any disrespect when I boasted my skill: however, be careful how you offend my serpent in your pride."

- Sudassana replied,

- 98. "Snake-charmer, I show disrespect to no one with my art; but you are deceiving people by showing off a harmless snake."

- 99. "Even thus too, I will make it known to all men, and you, Âlamba, will not get a handful of chaff, where then thy wealth?"

- At this the snake-charmer was enraged and said:

- 100, 101. "Hermit, clothed in dark garments,[2] with thy knot of hair,[3] who hast come into this assembly and insulted my serpent, do but approach him, full of virulent poison, and he will consume thee like chaff."

- [2. The Mandalay MS. has Khurâjino and says some read Kharâjino, the first word meaning a cloth dyed with black wood and hoofs, and the latter rough black dyed.

- p. 116

- Sudassana answered in jest,[1]

- 102. "It is true that rat snakes, slow worms, and green snakes are poisonous, but not so the red-headed Nâga."

- The Snake Charmer.

- 103, 104. "Hermit, I have heard that people have gone to Svagga by appeasing hermits with offerings. Therefore, if you have aught to give in alms, give it whilst you have got life. My serpent is mighty, and I will make him bite you and reduce you to ashes: before you die from his bite, make an offering, so that you may go to Svagga."

- 105. "I too have heard, friend, that men in this world have gone to Svagga through giving alms to pure hermits. If aught you have to give, give now whilst you yet live."

- [1. Or, with a view to raising a laugh.]

- p. 117

- 106. "Give alms. For Ajamukhî is also very poisonous, and I will cause her to bite thee and reduce thee to ashes."

- 107. "She is the daughter of Dhatara.t.tha, the King of Nâgas; she is my sister and the daughter of my aunt. Her fangs are full of poison and very sharp, and she shall straightways bite thee."[1]

- Then he cried, "Ajamukhî, come forth from my top-knot, and stand in my hand." Then, opening his hand, he stood in the midst ot the assembly, and Ajamukhî, uttering three cries, leapt on to his shoulder, and dropped three drops of poison into his hand, and then went back into the knot of hair. Then Sudassana shouted with a loud voice and said, "Now shall the kingdom of Bârâ.nasi be destroyed." His shout went through the whole kingdom of Bârâ.nasi, even to the distance of twelve yujana.

- Sudass.

- 108. "Know'st not King Brâhmadatta, if I was to pour out this poison on the earth all the grass, creepers and herbs would dry up?"

- [1. Above Accimukhi is said to be Vemâtikâ born of a different mother, which the Burmese has translated daughter of an aunt; really she was his half-sister.]

- p. 118

- 109. "And know'st thou not, Brâhmadatta, that were I to throw it upwards, for seven years this sky would drop neither rain nor dew?"

- 110. "And know'st not, Brâhmadatta, that were I to throw it into the water, every water-creature would die, both fish and turtles?"

- King. "Then, Hermit, I know not where you are to throw the poison, but please find some place, or my kingdom will be destroyed."

- Sudass. "Dig me here three pits in a line."

- When the pits were dug, Sudassana filled one with drugs, the middle one he ordered to be filled with cow dung, and into the third he put some fairy medicines. Then he cast the three drops of poison into the first hole, and instantly flame and smoke burst forth, which caught the cow dung in the middle pit, and then passing to the third pit was extinguished there.

- The snake-charmer was standing near the holes, and the flames taking hold of him, his skin peeled off, so that he became a white leper, on which, in his terror, he cried out thrice, "I release the Nâga King."

- On hearing this, Bhûridatta came forth from his basket, showing his jewelled body, resplendent, like Sakka himself. Sudassana and Ajamukhî also showed themselves in their true forms.

- Then said Sudassana, "Râjâ, do you not know us? Know you not whose children we are? Have you forgotten that Samuddajâ, the daughter of the Râjâ of Kâsi, was given in marriage to Dhattara.t.tha, the King of Nâgas?" "Yes," said the Râjâ, "she was my sister." "O Râjâ, we are her children and you are our uncle."

- The King then embraced Sudassana and Bhûridatta, and, p. 119 having taken them into the palace, made them presents, and said, "Dear Bhûridatta, since you are so powerful, how came you to get into the clutches of this snake-charmer?"

- Bhûridatta then told him the whole story.

- Then Sudassana said, "Dear uncle, our mother is in great distress at not hearing any tidings of Bhûridatta; we cannot stay, but must depart."

- The King replied, "Very good, go quickly, but I, too, should like to see my sister. How can it be managed?"

- Then Sudassana asked after his grandfather, and the Râjâ told him that he was so terrified that the day after he had given Samuddajâ in marriage, he had relinquished his kingdom and become a hermit. Sudassana then told the Râjâ that if he would appoint a day, they would bring their mother to meet him at their grandfather's hermitage. The Râjâ then conducted them on their journey, and they returned to serpent-land.

- CHAPTER. IV. (Micchâditthikathâ.)[1]

- When Bhûridatta returned, the whole country was convulsed with weeping, and he, being much distressed by a month's confinement in the

snake-charmer's basket, retired to sleep in his palace. Innumerable numbers of Nâgas came to see him, but he was unable to converse with them on account of his weakness. Kâ.nâri.t.tha, who went to Deva-land, and returned home before him, placed a guard at the palace door to prevent the people going to see Bhûridatta.

- Subhoga, having searched the whole of the Himavanta, was returning by the Yamunâ. Now the Brahman Nesâda, when he saw the snake-charmer become a leper, thought that, as he had coveted the ruby and taken part in the affair, some terrible calamity would overtake him; so he determined to go to the Yamunâ and bathe himself. He therefore went down to the bathing-place[2] and entered the

- 2. Payâga ti.t.the, now Allahabad.]

- p. 120 water. Just at that moment Subhoga arrived there too, and, hearing Nesâda make his confession, said, "This is the wretch who, through covetousness for my brother's ruby, not content with the great wealth that he had offered him, pointed him out to the snake-charmer. I will slay the villain." So coiling his tail round the Brahman, he dragged him under the water. Being tired, he allowed the Brahman's head to come up, and then dragged him down again. At last the Brahman got his head up, and was able to say:

- 111. "What demon is this who swallows up me, who have descended into the river Yamunâ and am standing at the bathing-place washing away with water my earthliness?"

- Subhoga answered:

- 112. "Wretched Brahman! I'm Subhoga,

- Son of Nâga Dhattara.t.tha,

- Him whose hood Benares city

- Overshadows, do'st not know me?"

- Nesâda thought, "Verily this is Bhûridatta's brother; if I cannot do something to preserve my life, he will undoubtedly slay me. I will try and soften his heart by praising the well-known splendour and tenderness of his parents." Then he said,

- p. 121

- 113. "If you are indeed the son of the Nâga King immortal, who rules over Kâsi, thy father is all-powerful, and thy mother the greatest lady upon earth; being then of such high descent, you ought not to drown a poor slave of a Brahman."

- Subhoga answered: "Hah! cursed Brahman, thinkest thou canst deceive me?"

- 114- 119. "You climbed into a tree to shoot a deer whilst it was drinking these waters, but not bringing it down, you had to follow its bloodstains. When you recovered it, you brought it in the dewy evening to a peepul tree, in whose branches cuckoos, cranes, parrots, and other birds disported, singing sweetly. At that peepul tree you saw my powerful elder brother, surrounded by his ladies in

all their splendour. He took you with him to fairy-land, and did he not endow you with great wealth? You have sinned against my brother, who was your benefactor, and p. 122 to whom you owed a debt of gratitude. Now the result of your evil deed has come upon you. Ha! Brahman, I will slay you, for the evil that you did to my brother. Stretch out your neck, for I will forthwith snap off your head. I will not give thee thy life."

- Then said Nesâda in a terrible fright:

- I who practise these three duties, ought not to be slain, O Brâhman."

- Subhoga replied:

- 121, 122. "The city of Dhattara.t.tha sunk 'neath Yamunâ's river,

- As they shall there give decree, so shall it be done to thee, Brâhman."

- Thus saying, he pushed and drew the Brahman Nesâda downwards, till he got to the gate of Bhûridatta's palace.

- When Kâ.nâri.t.tha saw Subhoga, he came towards him and said, "Brother, do not hurt this man, he is a Brahman, and a descendant of Brahma; if the Lord Brahma were to know that you had injured him, he would be very angry, and say, 'Are these Nâgas to ill-treat my children?' He might even destroy this country. In this cycle Brahmans are p. 123 noble and their power great. You, perhaps, know not the power of Brahmans."

- He then said to Subhoga and the other Nâgas, "Come here, and I will explain to you the qualities of sacrificial Brahmans."

- Vessas for tilth; and servants of all the Suddas,

- Each one severally in his own station

- Was created and placed, they say, (by Brâhma)."

- 125. "O brother, the Devas Dâtâ, Vidâtâ, Varuna, Kuvera, Yâma, Suriya, and Candimâ have arrived at their present state through having made offerings to Brahmans."

- [1. Ariyâ stands for Brahman, and janindâ for the Kshattriyas.]

- p. 124

- 126. "There was a king named Ajjuna (Arjuna), who was such a terrible warrior (bhîmaseno) that he could draw a bow equal in strength to 500 bows, as if he had a thousand arms, but he made offerings to fire (jâtavedam)."

- 127. "Subhoga, there was once a king in Bârâ.nasi made an offering of rice to the Brahmans, and he is now a powerful Deva."

- 128. "There was a king named Mucalinda, who was very hideous, but he made offerings to the fire god with clarified butter, and he is now in Deva-land. One day, in the city of Bârâ.nasi, he sent for the Brahmans and asked them the road to Deva-land, and they answered, 'O King. you must do honour to the Brahmans and their god.' 'Who is your god, O Brahmans,' he enquired; and they answered, 'He is the spirit of fire; satisfy him with butter made from cows' milk.' Mucalinda did as he was commanded."[1]

- p. 125

- 129. "The excellent (u.lâro) King Dudipo too, who was handsome, lived to a thousand years, and of great power, relinquishing his kingdom and army, became a hermit and went to Sagga."

- 130. "There was a king named Sâgara, who subdued the countries on the further side of the Ocean, and making a sacrifice of pure gold to the fire-god, established his worship. For that good deed he is now a Deva."

- 131. "Again, a king named Anga, through whose glory and power the river Ganges came into existence, and the ocean of curds and milk was produced. This king, on the soles of whose feet there was long hair, inquired how he was to get to Svagga, they told him that he might go into the Himavanta, and sacrifice to the Brahmans and fire. He went there, taking with him many oxen and buffaloes, and when the Brahmans had eaten, he asked what was to be done with what was left, and they told him to throw it away. In the spot where he threw it, there sprang up a river which was the Ga.ngâ."

- 132. "Subhoga, there was a certain powerful deva, a general of Sakko's army, who by soma[2] sacrifice cleansed himself from that which is vile."

- [2. The Mandalay MS. makes Soma to be a river of that name. The lomapâdo of verse 131 ought, I think, to be Somapado.]

- p. 126

- 133, 134. "Brahma, who created this world, the rivers Bhagirati, the Himavanta and the Gijjha mountains, when he was a man, sacrificed to fire. They say, too, that the other mountains Malâgiri, Viñjha, Sudassana, Kâkaneru, etc., were created with bricks through sacrificing to fire.[1] Subhoga, do you know how the salt water of the ocean came into being? No, you do not, but you know how to ill-treat them (Brahmans) and know nothing of their good qualities."

- 135. "Listen to me, the Ocean caused the death of a Brahman who was versed in the Vedas, performed his duties strictly, and was ever ready to receive, therefore we may never drink its waters."

- [1. Has this any reference to volcanic action?]

- p. 127

- 136. "These Brahmans, Subhoga, are like the surface of the earth in which we ought to plant the seeds of good works. On the east, west, south and north, Brahmans are the only things we ought to desire."

- Thus Ari.t.tha, in fourteen gâthâ, praised Brahman sacrificial rites and the Vedas.

- CHAPTER V. (The Bodhisat's Discourse)

- At that time all the Nâgas there assembled thought that what Ari.t.tha said was true, and Bhûridatta lay there listening to him; so, in order to dispel the wrong impression that had been given them, he thus addressed them: "Kâ.nâri.t.tha, what you have said regarding sacrifice and the Vedas is not true; the Brahmans by their arrangement of the Vedas cannot be considered good men.

- After this he recited the following twenty-seven stanzas, to show the erroneous practices of Brahmans:

- 137. "Loss to the wise, a gain to fools, is skill in the Vedas, Ari.t.tha; mirage-like when reflected on, their delusions take away wisdom."

- 138. "The Vedas are no protection to any one, not even to the perfidious and evil man. The worshipped fire too, gives no protection to the evil-doer."

- p. 128

- 139. "Rich and wealthy mortals may set fire to food mixed with grass, but who can satisfy it? Fire, which is unlike all else, cannot be satisfied, O double-tongued one.

- 140. "As milk by its changeable nature turns to curd and also to butter; so fire, by its changeable nature, is made by him who uses the fire-sticks."

- 141. "One sees not the fire that is inherent in the dry wood or green. If the fire-stick is rubbed not by man, fire is not made, it burns not."

- 142. "If fire dwell hidden both in dry wood and green too, all the green would be dry in this world; the dry wood would burst into flames."

- p. 129

- 143. "If one makes merit with the smoke and flame of wood and grass, then charcoal-burners, salt-boilers, cooks and even corpse-burners would heap up to themselves merit."

- 144. "If they in truth do not a good deed, no one in this world can get merit by appeasing the Brâhminical fire."

- 145. "Wherefore does this world, revered being, eat, O double-tongued one, things which smell bad and which are rejected?"

- 146. "Some say that flame is a god, and Milakkhas (heathens) say that water is a god, but all have a wrong opinion; fire is not one of the gods, nor water."

- 147. "How shall evil-doers go to heaven by doing honour to fire, which is perceptibly mindless and the servant of men?"

- p. 130

- 148. "You say that Brahma became the ruler of all things through serving fire here in this life. If he created all and controls all, the uncreated worships the created."

- 149. "A thing to be derided, a lie; wishing to be honoured they have lied of old; they for their own gain which was not before apparent have concocted their own law for men."

- 150. "(Which is) For teaching Ariya, for the earth men rulers, Vesyas for tilth, as servants of all Suddas. Each for his own station were made, they say, by Brahma."

- 151. "If these words were true as spoken by the Brahmans, none but Khattiyas would reign, none but Brahmans would teach wisdom's sayings."

- 152. "None but Vesyas would till land; Suddas would not be free from service; these words are false: they speak lies for the sake of their bellies."

- p. 131

- 153. "Such things fools only believe, wise men and they themselves see through it: Khattyas pay tribute to Vesyas, and Brahmans go about carrying weapons: such a shaken-up, scattered world, why does not Brahma put straight?"

- 154. "If verily Brâhmâ rules the world, and if he be the great king of men, how can he behold the world thus unfortunate, why does he not make the whole world happy?"

- 155. "If verily Brâhmâ the king of the world be lord of all mortals. By delusion, lying, magic and lawlessness, why has he made this world?"

- 156. "Verily if Brâhmâ be the lord of the world and ruler of all beings, he is a lawless ruler, Ari.t.tha; though there be law, he rules lawlessly."

- p. 132

- 157. "'Caterpillars and insects, snakes and frogs, and worms, and flies,[1] they slay and are innocent;' these opinions of the people of Kamboja are dishonourable (non-Brahminical); they are false."

- 158. "If he is pure who slays, and the slayer enters Svagga, would not the Brahmans slay one another, and those too who believe in them?"

- 159. "Nor wild beasts, nor cattle, nor oxen, request their own slaughter; there whilst alive they struggle at the sacrifice; they drag cattle by exertion."

- 160. "Those fools having bound cattle to the post, with vanity make bright your face (saying), 'This sacrificial post will give you all desires in the next world, and they will last in the future.'"

- p. 133

- 161. "Verily, if there be silver, gold, gems, shells and all kinds of wealth in the sacrificial post, in green wood and dry too, and all the delights of Deva land, all those Brâhmans would sacrifice abundantly, there is not a Brâhman who would not sacrifice."

- 162. "How can gems, etc., and all the delights of the Devas, be in a post in green wood and dry too?"

- 163. "Both wicked, cruel, covetous and fools, rejoicing in all sorts of vanities (they say) take fire, to me give wealth; then be blessed and have all you desire."

- 164. "Taking refuge in sacrifice, they rejoice with various vanities."

- p. 134

- 165. "Like crows who have found an owl alone, they surround one in flocks, and having eaten one's victuals they make a clean shave of one, and throw one away at the sacrificial post."

- 166. "Thus, deceived by the Brâhmans, being alone and they many: they with their sayings get present wealth, for that which is unseen (illusory)."

- 167. "When made their advisers by kings they carry off wealth. They are such thieves, and worthy to be executed, yet are not slain."

- 168. "In the sacrifice they cut the palasa pole, saying it is the right arm of Indra; if that be true and Maghava is deprived of his arm, with what does Indra subdue the Asuras?"

- 169. "That too is false, for Maghava being all-powerful, slays them; he is the chief Deva and cannot be slain. These Vedas are false, they are illusions visible to all men."

- p. 135

- 170. "Mounts Nâlâ, Himavayo, Gajjho, Sudassana, Nisabhogo, Kâkaneru, these and other great mountains were brick made in sacrifice they say."

- 171. "In this manner with bricks they are built in sacrifice, they say: mountains are not made thus, they stand firm and unshaken, being of a different nature."

- 173. "They say that a strict and learned hermit was swallowed up by the water when bathing on the shores of the ocean, and it is therefore undrinkable."

- p. 136

- 174. "More than a hundred virtuous hermits learned in the Vedas have the rivers slain; their waters are not undrinkable. Why, then, is the incomparable ocean undrinkable?"

- 175. "Here in this living world there are salt-water holes that have been dug: these have not slain Brâhma.ns; but, O two-tongued one, why is not their water undrinkable?"

- 176. "In the beginning of ages to whom was there a wife? Firstly, mind created man. Therefore no one was base, and so in like manner they say is the determination of Sagga."

- 177. "Should a Candala learn the Vedas, and recite its verses, though intelligent and virtuous, his head would be split into seven pieces: they have made the verses for the purpose of slaying."

- 178. "They teach words made for the sake of gain."

- p. 137

- 180. "Verily, if a king subdued the whole world and his councillors were obedient, he would conquer all his enemies, and his subjects would ever be happy."

- 181. "The instructions for Khattiyas and the three Vedas are similar in purpose, and not being able to discern their deception, one cannot know a word, as it were, covered with water."

- 182. "The instructions for Khattyas and the three Vedas are one in their purpose: profit and loss, honour and dishonour, these are the rules of those four castes."

- 183. "And as rich men desiring wealth and corn do much tillage on the earth, so these Brahmans and Suddas do many works on earth."

- p. 138

- 184. "They are like unto wealthy men, they are ever energetic in pleasure, they do much tillage upon the earth; but, O double-tongued one, they are witless in their pleasures."