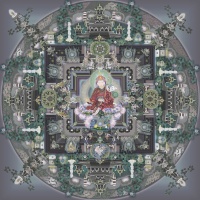

Mandala

Maṇḍala (मण्डल) is a Sanskrit word meaning "circle." Mandalas have spiritual and ritual significance in Hinduism and Buddhism.

The term is of Hindu origin. It appears in the Rig Veda as the name of the sections of the work, but is also used in other Indian religions, particularly Buddhism.

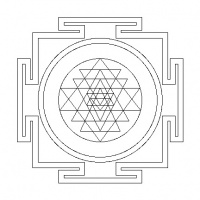

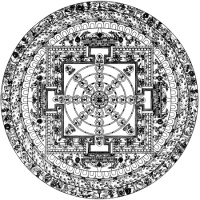

The basic form of most Hindu and Buddhist mandalas is a square with four gates containing a circle with a center point. Each gate is in the shape of a T. Mandalas often exhibit radial balance.

In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of aspirants and adepts, as a spiritual teaching tool, for establishing a sacred space, and as an aid to meditation and trance induction. In the Tibetan branch of Vajrayana Buddhism, mandalas have been developed into sand painting. They are also a key part of Anuttarayoga Tantra meditation practices.

In common use, mandala has become a generic term for any plan, chart or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically, a microcosm of the universe from an enlightened perspective, i.e. that of the principle deity.

Hinduism

Religious meaning

A yantra is a two- or three-dimensional geometric composition used in sadhanas, or meditative rituals. It is thought to be the abode of the deity. Each yantra is unique and calls the deity into the presence of the practitioner through the elaborate symbolic geometric designs. According to one scholar, “Yantras function as revelatory symbols of cosmic truths and as instructional charts of the spiritual aspect of human experience"

Many situate yantras as central focus points for Hindu tantric practice.Yantras are not representations, but are lived, experiential, nondual realities. As Khanna describes:

- Despite its cosmic meanings a yantra is a reality lived. Because of the relationship that exists in the Tantras between the outer world (the macrocosm) and man’s inner world (the microcosm), every symbol in a yantra is ambivalently resonant in inner-outer synthesis, and is associated with the subtle body and aspects of human consciousness.

Political meaning

The "Rajamandala" (or "Raja-mandala"; circle of states) was formulated by the Indian author Kautilya in his work on politics, the Arthashastra (written between 4th century BC and 2nd century AD). It describes circles of friendly and enemy states surrounding the king's state.

In historical, social and political sense, the term "mandala" is also employed to denote traditional Southeast Asian political formations (such as federation of kingdoms or vassalized states). It was adopted by 20th century Western historians from ancient Indian political discourse as a means of avoiding the term 'state' in the conventional sense. Not only did Southeast Asian polities not conform to Chinese and European views of a territorially defined state with fixed borders and a bureaucratic apparatus, but they diverged considerably in the opposite direction: the polity was defined by its centre rather than its boundaries, and it could be composed of numerous other tributary polities without undergoing administrative integration. Empires such as Bagan, Ayutthaya, Champa, Khmer, Srivijaya and Majapahit are known as "mandala" in this sense.

Buddhism

[[File:Painted_manda.jpg|thumb|250px|Painted 17th century Tibetan 'Five Deity Mandala', in the center is Rakta Yamari (the Red Enemy of Death) embracing his consort Vajra Vetali, in the corners are the Red, Green White and Yellow Yamaris, Rubin Museum of Art)]

Early and Theravada Buddhism

The mandala can be found in the form of the Stupa and in the Atanatiya Sutta in the Digha Nikaya, part of the Pali Canon. This text is frequently chanted.

Tibetan Vajrayana

- See also:Vajrayana

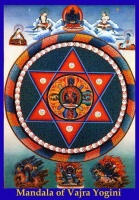

Visualisation of Vajrayana teachings

The mandala can be shown to represent in visual form the core essence of the Vajrayana teachings. The mind is "a microcosm representing various divine powers at work in the universe." The mandala represents the nature of experience, and the intricacies of both the enlightened and confused mind.

While on the one hand, the mandala is regarded as a place separated and protected from the ever-changing and impure outer world of samsara, and is thus seen as a "Buddhafield" or a place of Nirvana and peace, the view of Vajrayana Buddhism sees the greatest protection from samsara being the power to see samsaric confusion as the "shadow" of purity (which then points towards it).

Mount Meru

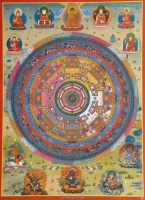

A mandala can also represent the entire universe, which is traditionally depicted with Mount Meru as the axis mundi in the center, surrounded by the continents.

Wisdom and impermanence

In the mandala, the outer circle of fire usually symbolises wisdom. The ring of eight charnel grounds represents the Buddhist exhortation to always be mindful of death, and the impermanence with which samsara is suffused: "such locations were utilized in order to confront and to realize the transient nature of life." Described elsewhere: "within a flaming rainbow nimbus and encircled by a black ring of dorjes, the major outer ring depicts the eight great charnel grounds, to emphasize the dangerous nature of human life." Inside these rings lie the walls of the mandala palace itself, specifically a place populated by deities and Buddhas.

Five Buddhas

One well-known type of mandala is the mandala of the "Five Buddhas", archetypal Buddha forms embodying various aspects of enlightenment. Such Buddhas are depicted depending on the school of Buddhism, and even the specific purpose of the mandala. A common mandala of this type is that of the Five Wisdom Buddhas (a.k.a. Five Jinas), the Buddhas Vairocana, Aksobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi. When paired with another mandala depicting the Five Wisdom Kings, this forms the Mandala of the Two Realms.

Practice

Mandalas are commonly used by tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation.

The mandala is "a support for the meditating person", something to be repeatedly contemplated to the point of saturation, such that the image of the mandala becomes fully internalised in even the minutest detail and can then be summoned and contemplated at will as a clear and vivid visualized image. With every mandala comes what Tucci calls "its associated liturgy [...] contained in texts known as tantras", instructing practitioners on how the mandala should be drawn, built and visualised, and indicating the mantras to be recited during its ritual use.

By visualizing "pure lands", one learns to understand experience itself as pure, and as the abode of enlightenment. The protection that we need, in this view, is from our own minds, as much as from external sources of confusion. In many tantric mandalas, this aspect of separation and protection from the outer samsaric world is depicted by "the four outer circles: the purifying fire of wisdom, the vajra circle, the circle with the eight tombs, the lotus circle." The ring of vajras forms a connected fence-like arrangement running around the perimeter of the outer mandala circle.

As a meditation on impermanence (a central teaching of Buddhism), after days or weeks of creating the intricate pattern of a sand mandala, the sand is brushed together and placed in a body of running water to spread the blessings of the mandala.

Kværne in his extended discussion of sahaja, discusses the relationship of sadhana interiority and exteriority in relation to mandala thus:

- ...external ritual and internal sadhana form an indistinguishable whole, and this unity finds its most pregnant expression in the form of the mandala, the sacred enclosure consisting of concentric squares and circles drawn on the ground and representing that adamant plane of being on which the aspirant to Buddha hood wishes to establish himself. The unfolding of the tantric ritual depends on the mandala; and where a material mandala is not employed, the adept proceeds to construct one mentally in the course of his meditation."

Offerings

[[File:Chenrezig_Sand_Man.jpg|thumb|250px|Chenrezig sand mandala created at the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on the occasion of the Dalai Lama's visit in May 2008]] A "mandala offering" in Tibetan Buddhism is a symbolic offering of the entire universe. Every intricate detail of these mandalas is fixed in the tradition and has specific symbolic meanings, often on more than one level.

Whereas the above mandala represents the pure surroundings of a Buddha, this mandala represents the universe. This type of mandala is used for the mandala-offerings, during which one symbolically offers the universe to the Buddhas or to one's teacher. Within Vajrayana practice, 100,000 of these mandala offerings (to create merit) can be part of the preliminary practices before a student even begins actual tantric practices. This mandala is generally structured according to the model of the universe as taught in a Buddhist classic text the Abhidharma-kośa, with Mount Meru at the centre, surrounded by the continents, oceans and mountains, etc.

Shingon Buddhism

The Japanese branch of Mahayana Buddhism -- Shingon Buddhism—makes frequent use of mandalas in its rituals as well, though the actual mandalas differ. When Shingon's founder, Kukai, returned from his training in China, he brought back two mandalas that became central to Shingon ritual: the Mandala of the Womb Realm and the Mandala of the Diamond Realm.

These two mandalas are engaged in the abhiseka initiation rituals for new Shingon students, more commonly known as the Kechien Kanjō (結縁灌頂). A common feature of this ritual is to blindfold the new initiate and to have them throw a flower upon either mandala. Where the flower lands assists in the determination of which tutelary deity the initiate should follow.

Sand mandalas, as found in Tibetan Buddhism, are not practiced in Shingon Buddhism.

Nichiren Buddhism

The mandala in Nichiren Buddhism is called a moji-mandala (文字曼陀羅) and is a paper hanging scroll or wooden tablet whose inscription consists of Chinese characters and medieval-Sanskrit script representing elements of the Buddha's enlightenment, protective Buddhist deities, and certain Buddhist concepts. Called the Gohonzon, it was originally inscribed by Nichiren, the founder of this branch of Japanese Buddhism, during the late 13th Century. The Gohonzon is the primary object of veneration in some Nichiren schools and the only one in others, which consider it to be the supreme object of worship as the embodiment of the supreme Dharma and Nichiren's inner enlightenment. The seven characters Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, considered to be the name of the supreme Dharma, as well as the invocation that believers chant, are written down the center of all Nichiren-sect Gohonzons, whose appearance may otherwise vary depending on the particular school and other factors.

Pure Land Buddhism

Mandalas have sometimes been used in Pure Land Buddhism to graphically represent Pure Lands, based on descriptions found in the Larger Sutra and the Contemplation Sutra. The most famous mandala in Japan is the Taima Mandala, dated to approximately 763 CE. The Taima Mandala is based upon the Contemplation Sutra, but other similar mandalas have been made subsequently. Unlike mandalas used in Vajrayana Buddhism, it is not used as an object of meditation or for esoteric ritual. Instead, it provides a visual representation of the Pure Land texts, and is used as a teaching aid.

Also in Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, Shinran and his descendant, Rennyo, sought a way to create easily accessible objects of reverence for the lower-classes of Japanese society. Shinran designed a mandala using a hanging scroll, and the words of the nembutsu (南無阿彌陀佛) written vertically. This style of mandala is still used by some Jodo Shinshu Buddhists in home altars, or butsudan.

Christianity

Forms which are evocative of mandalas are prevalent in [[Wikipedia:Christianity|Christianity]]: the celtic cross; the rosary; the halo; the aureole; oculi; the Crown of Thorns; rose windows; the Rosy Cross; and the dromenon on the floor of Chartres Cathedral. The dromenon represents a journey from the outer world to the inner sacred centre where the Divine is found.

Similarly, many of the Illuminations of Hildegard von Bingen can be used as mandalas, as well as many of the images of esoteric [[Wikipedia:Christianity|Christianity]], as in Christian Hermeticism, Christian Alchemy, and Rosicrucianism.

Western psychological interpretations

According to the psychologist David Fontana, its symbolic nature can help one "to access progressively deeper levels of the unconscious, ultimately assisting the meditator to experience a mystical sense of oneness with the ultimate unity from which the cosmos in all its manifold forms arises." The psychoanalyst Carl Jung saw the mandala as "a representation of the unconscious self," and believed his paintings of mandalas enabled him to identify emotional disorders and work towards wholeness in personality.

Australian usage

A Bora is the name given both to an initiation ceremony of Indigenous Australians, and to the site Bora Ring on which the initiation is performed. At such a site, young boys are transformed into men via rites of passage. The word Bora was originally from south-east Australia, but is now often used throughout Australia to refer an initiation site or ceremony. The term "bora" is held to be etymologically derived from that of the belt or girdle that encircles initiated men. The appearance of a Bora Ring varies from one culture to another, but it is often associated with stone arrangements, rock engravings, or other art works. Women are generally prohibited from entering a bora. In South East Australia, the Bora is often associated with the creator-spirit Baiame.

Bora rings, found in south-east Australia, are circles of foot-hardened earth surrounded by raised embankments. They were generally constructed in pairs (although some sites have three), with a bigger circle about 22 metres in diameter and a smaller one of about 14 metres. The rings are joined by a sacred walkway. Matthews (1897) gives an eye-witness account of a Bora ceremony, and explains the use of the two circles.

The word mandala (dkyil ‘khor) in Tibetan actually means centre and periphery, i.e. a circle: the circle of a king, a magician’s circle, an organization with a centre (chairman) and periphery, and so on.

In Buddhist meditation there are many kinds of mandala, A mandala is the way we experience the world (samsara), inclusive of a kind of centre (the experiencer) and the periphery (the experienced). It includes the tone (emotional/intellectual) of that experience; it is both quantitative and qualitative – albeit the purpose of Buddhist meditations is to change/transform the qualitative aspect. This would mean change in the perceiver/experiencer, the quality of the experience thereof and the experienced. It can be said that a restructuring of emotional and thinking patterns takes place in this kind of mandala change.

A mandala is one’s existential situation, with oneself as the centre and one’s experience as the periphery of the mandala. The way we see/feel/experience our situation this very moment, here and now, is our mandala. Of course this bring us to the problem that we do not experience this moment in all its fullness/completeness/perfection. That is why it is called Ignorance Mandala. It is painted by ignorance, so we are incapable of experiencing the richness of the moment. If we could, every moment or experience would be the great perfection – nothing to add, nothing to subtract. Thus the purpose of Buddhist meditation is to transform the Ignorance Mandala into the Wisdom Mandala.

Besides these two basic varieties of mandalas, i.e. the Ignorance Mandala and Wisdom Mandala (ajnana mandala and jnanaa mandala), we as individuals have an infinite number of mandalas - the poet mandala, the artist mandala, the father-mother mandala, the lover mandala, the husband-wife mandala, the school teacher/managing director mandala etc. We are constantly moving from one mandala to the other, but due to individual grasping the transitions may not be so smooth or we may even transmute a give mandala through our fixation on it into a perilous “me” mandala, the ajnana mandala, imagining it to be our basic identity. But samsara is in flux, and so a fixed identity mandala is untenable. Thus there is friction – sorrow. The first tenet of Buddhism is to realize the need to be able to let go of any fixation on any mandala or group of mandalas and to be able to flow freely within the infinite dimensions (mandalas) of the mind. This is the purpose of all Buddhist meditation. As Zen master say, “When hungry I eat, when tired I sleep.” When we can really do that, without memories of the past, imaginations of the future distorting the moment mandala, we are in the jnana mandala. This is the state without grasping or rejecting, without hope for a better situation mandala or fear of a worse mandala. In other words of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, this state is completely hopeless, i.e. free of hope and fear. Such a state is free of meditation or no-meditation; this is why it is called non-meditation. All Buddhist meditation techniques aim towards this state. In fact, non meditation is the only true meditation. All other forms of meditation are only attempts to meditate.

To transform the ajnana mandala into the jnana mandala we need to let go, stop fixating. In order to let go or stop fixating, it is crucial to gain insight (vipashyana) into the fact that the centre of the mandala is centreless or, in more orthodox terms, empty (shunyata) or anatma (no-self). Centre-less-ness is the centre and the periphery is peripheryless, i.e. again empty. As the Pali text says, sabbe dhamma anatta, i.e. all dharmas (centre and periphery) are empty of a self. In Mahayana language, this is called pudgala nairatmya and dharma nairatmya. This is the jnana mandala in Vajrayana. The mandala is thus a true existential application of the Buddha’s teachings. This is the mandala as the ground/bhumi.

The mandala as the path/marga can be divided into three types. The first is the body mandala of the Mahayoga. The deities in thangkas belong to this group. These mandalas are used to transform the conception of ordinary bodies and their mandalas into Deity bodies and their mandalas through meditation. This Mahayoga-level mandala is a whole and restructured way of perceiving the perceiver and the perceived, inclusive of emotional tones, language structures, thinking patterns and styles of interpreting. For example, diseases are diagnosed or interpreted in terms of male spirits, female spirits and nagas. Devas, nagas etc. are the language structure and though patterns of this group of mandalas.

The second class of mandalas is called Anuyoga or the mandalas of nadi chakras. Here, samsara again is reconstructed into a new pattern of vision. The language structures etc. again change even though it is the same samsara, that is, even though we are still talking about the same thing. All the deities become seed mantras. Diseases now are diagnosed or interpreted as imbalances in the channels and winds. We have to understand that this is just a user of another vision (language structures, thinking patterns) for the same thing as the male spirits, female spirits and nagas of the Mahayoga.

The third class of mandalas is that of the Atiyoga. Its members could also be called mind mandalas. Here, everything is treated in terms of the mind, or as unity of emptiness and luminosity. Diseases are seen as an imbalance of emptiness and luminosity etc.

These three mandala categories are not exclusive but are three different ways of perceiving samsara. They are used s the path (meditation) to bring about a transformation from Ignorance Mandala to Wisdom Mandala.