Instructions on “Differentiating the Middle from the Extremes“ by Buddha Maitreya / composed by Asanga Chapters 4 & 5 & Conclusion

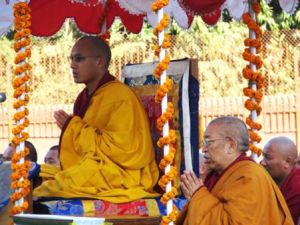

presented at Thrangu Tashi Chöling in Boudhnath, Nepal

</poem>

4. The Phases and Results of Meditation

4.1. Identifying the Five Paths in General

4.2. In Detail

4.2.1. The Five Faults

4.2.2. The Eight Antidotes

4.2.3. The Three Occasions of the Five Paths

4.2.4. The Path of a Bodhisattva

4.2.5. The Phases of the Paths

4.2.5.1. Nine Phases

4.2.5.2. Three Phases

4.2. The Five Results

4.2.1. In General

4.2.2. In Detail

5. The Unsurpassable Vehicle

5.1. The Unsurpassable Practices

5.1.1. The Twelve Excellent Features

5.1.2. The Ten Paramitas

5.1.3. The Ten Dharma Activities

5.1.3.1. In Brief

5.1.3.2. In Detail

5.1.3.2.1. Shamata

5.1.2.2.2. Vipassana

5.1.4.. Abandoning the Two Extremes

5.2. The Unsurpassable Observation

5.3. The Unsurpassable Accomplishment

D. Concluding Words

Prayers </poem>

4. The Phases and Results of Meditation

The objective of Buddhism is to achieve Buddhahood and thus to become a Buddha. The term “Buddha” in Sanskrit was translated into Tibetan as Sangyä and consists of two syllables. Sang means ‘cleansed, purified’ and refers to the abandonment of obstructions that are to be abandoned. The second syllable rgyäs means ‘to expand, enlarge, extend’ and refers to the realisation of what there is to be realised. This process of cleansing and expanding our awareness is accomplished through meditation practice, and therefore meditation is very important. We also speak of “Bodhi,” which is byang-chub in Tibetan. It refers to ‘enlightenment,’ i.e., ‘the awakened mind.’ The syllable byang means ‘to cleanse,’ in particular to dispel obstructions. The syllable chub means ‘to master, to accomplish,’ in particular to develop all good qualities completely and perfectly.

Generally speaking, the text “Differentiating the Middle from the Extremes” consists of five chapters. The first chapter is about the definitive characteristics of the way in which all things exist and abide. The second chapter is a discussion of the reason sentient beings wander in samsara, and the reason is the various obstructions that exist within their continuum or mind stream. And so, the second chapter of this treatise is given over to a discussion of the obstructions. The method to abandon such obstructions is to realise Dharmata, ‘suchness.’ To facilitate such realisation, the Regent Maitreya offered explanations in the third chapter of this treatise. These three chapters have so far been covered in this seminary.

The way in which Dharmata is to be realised is through engaging in the paths that serve as the antidotes to the obstructions in our mind stream and in that way to cast them out. So the fourth chapter is a discussion of the paths that serve as antidotes to the obstructions. It is divided into three sections. They are: identifying the paths, the stages of development along the paths, and the result of practicing the paths.

4.1. Identifying the Five Paths in General

The 37 harmonies with enlightenment, which were explained in the second chapter of this treatise, are the body of the five paths, i.e., they are the paths. They are the agents that actually dispel the obstructions. That is why they are identified in the section on the five paths so that they are known and cultivated. The explanation of the 37 harmonies with enlightenment in the fourth chapter is similar to that made earlier, but specific features are further explained here. It is not necessary to repeat what has been explained, but there is a purpose to speaking about what has been added.

As discussed earlier, the path of accumulation is divided into three parts, small, middling, and great. On the small part of the path of accumulation we practice the four foundations or close-placements of mindfulness. Since our physical body is the root of suffering, the first foundation is (1) mindfulness of our body. If we understand the body well, we will also understand true suffering well. The second close-placement is (2) mindfulness of our feelings. What is the purpose for practicing this? Afflictions are caused by craving, which is caused by feelings. If we understand the nature of our feelings, we will be able to relinquish our craving and thus will be able to abandon our afflictions. This practice is related to understanding the Second Noble Truth, which is the truth of the origins of suffering. The third close-placement is (3) mindfulness of our mind’s lack of a self. It is a method to understand and actualize the Third Noble Truth, the truth of cessation. The fourth close-placement is (4) mindfulness of phenomena. It is related to the Fourth Noble Truth, which is the true path. If we understand, without obscurations and without error, the phenomena of samsara and the meaning of nirvana, then we can give rise to true paths in the continuum of our being. That is why it is important to understand phenomena and to cultivate this close-placement of mindfulness. The middling path of accumulation consists of practicing the four genuine abandonments. It is described in the same way as it was taught in the second chapter of this treatise.

The great path of accumulation is the occasion of developing the four legs of magical emanations. These four legs are principally samadhi (‘meditative stabilisation’). The text gives an outline of the methods of meditation, in particular, there is a discussion of five faults that occur during meditation practice and eight antidotes that we can apply. The procedures presented here are from Sutrayana and not from Mantrayana. They are basic matters that need to be practiced by everyone and therefore they are discussed in the detailed description.

4.2. In Detail

We can discuss meditation in terms of beginning to meditate, application, becoming accustomed to the practice, the actual practice, and the conclusion.

4.2.1. The Five Faults

The first fault that obstructs us from even engaging in meditation is (1) laziness. The second fault is (2) forgetting the oral instructions. The oral instructions, which are explanations that inform us about the benefits of practicing and the disadvantages of not practicing, motivate us to begin practicing. So, it is important to remember the oral instructions. Furthermore, the oral instructions are explanations on how to meditate. So, it is important not to forget them. Two faults can occur while meditating. They are (3) stupor and (4) excitement. During meditation, our mind can sink and become heavy and depressed. At other times, our mind can run all over the place and be wild. (5) Reacting and not reacting is the fifth fault and means that we need to recognize when our mind sinks, when it is excited, and how to apply the antidotes to those faults. We also need to recognize whether our mind has not sunk and is not wild and then know that we do not need to apply an antidote.

4.2.2. The Eight Antidotes

The first four antidotes are applied when we notice that we have succumbed to the fault of laziness. These four antidotes are: (1) – (4) faith, aspiration, exertion, and being thoroughly pliant. The fourth (pliancy, subtleness) is the actual antidote to laziness. Once we have such subtleness of body and mind, then it is possible for us to remain comfortable in meditation, no matter how long the session lasts. How do we develop such subtleness? By applying exertion, which we win by having aspiration or inspiration. This means liking meditation and because we have realised that it is very important, we long to practice. Where does aspiration come from? Because we know that meditation is an activity that is not like any others and that the benefits of meditating are not like anything else, we have faith in meditation. Having that view and faith and being confident that our wisdom will increase through meditation, our practice becomes indispensable for us.

The fifth from among the eight antidotes or applications is (5) mindfulness, which serves as the antidote to forgetting the oral instructions and which causes us to remember and to stay aware of them during meditation and after meditation sessions. (6) Recognising faults is the sixth antidote to stupor and excitement. It is the ability to recognize these states of mind so that we can abandon them. (7) The antidote to the fifth fault of reacting or not reacting is literally translated as “intention” and means turning our mind towards the proper antidote. The eighth antidote to the fault of applying unnecessary antidotes is (8) equanimity. This means that instead of applying an antidote when our mind has not become dull or is not excited, we just rest our mind in a very relaxed, easy, and comfortable way.

4.2.3. The Three Occasions of the Five Paths

The discussion at this point is not very different than the earlier one. But it is important to understand that in dependence upon the 37 harmonies with enlightenment, we move from the path of accumulation to the path of joining and then to the path of seeing. Following is the path of meditation and finally there is the path of no more learning. Thus, this presentation is a discussion of the way in which the fruit of practice can be achieved by following the paths.

The five paths can be subsumed into three groups. Since they are not the paths of superior beings, (1) the path of accumulation (tshogs-lam) and the path of joining (byor-lam) are said to be mistaken; but they do lead to what will later be realised by a superior being. They are called “mistaken” due to the fact that a practitioner does not realise Dharmata while practicing these paths. Therefore, because they are based on the fact that practitioners are partially mistaken, these two paths are grouped together. The second of these occasions is (2) the third path of seeing (mthong-lam). On the path of seeing, a superior being sees Dharmata directly and in that way has passed beyond error. It represents the second group. The third group is (3) the path of meditation (sgom-lam) and the path of no more learning (mi-blob-pa’i-lam). At this time, a superior practitioner achieves the results of practice, is in a non-mistaken state, and is free of error.

4.2.4. The Path of a Bodhisattva

The path of a Bodhisattva is discussed in terms of the 37 harmonies with enlightenment and in terms of the three different occasions of the path. The exceptional features of the Bodhisattva’s paths are described as the special way in which Bodhisattvas develop their mind. This has three aspects. The first is (1) the object of observation. Shravakas (‘hearers’) and Pratyekabuddhas (‘solitary realisers’) are concerned with their own welfare and strive to achieve lasting happiness for themselves; they meditate on the no self of the individual to achieve this goal. Bodhisattvas take to mind how to accomplish the welfare of all sentient beings; so they meditate on the no self of the individual as well as on the no self of phenomena to achieve this goal. The second way in which a Bodhisatta’s path is elevated above the Hinayana paths of Sharvakas and Pratyekabuddhas is in terms of (2) mental application. Shravakas and Pratyekabuddhas meditate on impermanence and suffering. Bodhisattvas do not just meditate on impermanence as the antidote to the conception of permanence, and they do not just meditate on suffering and misery as the antidote to the conception of suffering in samsara. They set their mind on that which is beyond permanence and impermanence, Dharmadhatu (chös-kyi-dbyings, ‘the sphere of phenomena, the limitless expanse of all things’). Thirdly, there is a great difference in terms of (3) the fruit or effect that is achieved by Hinayana practitioners and that which is achieved by Bodhisattvas.

4.2.5. The Phases of the Paths

4.2.5.1. Nine Phases

When that paths are categorized as nine phases, the first occasion is called (1) “entrance.” It refers to awakening the potential for enlightenment that exists within oneself and everyone else and feeling great joy about having done so. The second occasion is (2) mind generation, i.e., turning our mind toward enlightenment and entering the path. The third is (3) joining. It is the period of time that we set our mind upon enlightenment, until we have achieved the first of the ten Bhumis (‘Bodhisattva grounds’). The fourth occasion is (4) the effect. It refers to having achieved the first ground. (5) Accomplishing actions is the fifth phase and refers to the period in which it is necessary to exert effort. It lasts until the seventh Bhumi has been reached. The sixth of the nine phases is called (6) “without striving and exertion.” It refers to having reached the eighth Bhumi, at which time a Bodhisattva no longer needs to exert effort while progressing to complete Buddhahood. On the ninth Bhumi, a Bodhisattva achieves the seventh of the nine phases, which is called (7) “distinct and special good qualities.” In particular, it is the achievement of what is known as “the four genuine knowledges.” (8) The elevated occasion is achieved on the tenth Bodhisattva Bhumi. It is superior to any other level of realisation that has been attained up to then. The ninth occasion is (9) Buddhahood itself and is given the name “the unsurpassable.”

4.2.5.2. Three Phases

The nine phases can be subsumed into three. The Root Text states: “There are three aspects in the Dharmadhatu: impure, impure and pure, as well as completely pure; they are described respectively. Based upon them and accordingly, the status of individuals is determined.”

The first phase, (1) impure, refers to the fact that while on the path of accumulation and joining and from our side, Dharmata is still covered with stains. The second, (2) partially pure, has to do with the next two paths. On the paths of seeing and meditation, more and more defilements are dispelled and thus Dharmata is progressively seen ever more clearly. In that all defilements have been removed, the third phase is called (3) “completely pure.” It is Buddhahood.

4.2. The Five Results

4.2.1. In General

The Root Text:

“(That which) becomes a vessel (and) has perfectly matured; influential power; wishes; increasing (abilities); and perfect purity are the results in subsequent order.”

4.2.2. In Detail

The first result of accomplishing the paths is (1) always having a good body, i.e., never being born as a hell-being or as a preta (‘hungry and frightened ghost’), rather, always having a good and healthy human body. Secondly, (2) having influential power means having the capability and ability to carry out beneficial activities, without every fluctuating. This ability to help others increases and becomes greater and greater. The third result is that a Bodhisattva’s (3) attitude is such that his/her wishes accord with the results and thus a Bodhisattva is continually joyous and delighted. The fourth result is (4) increasing abilities. They arise from having become familiarized with carrying out beneficial activities over a period of many lifetimes. The fifth result is (5) perfect purity, which means being totally separated from that which is discordant with the Bodhisattva path. In that way, the effects that are experienced from practicing the paths can be summarized and characterised in terms of the five results.

The Root Text:

“That was the fourth chapter, entitled ‘The Antidotes: The Phases and Results of Meditation,’ from ‘Differentiating the Middle from the Extremes.’”

5. The Unsurpassable Vehicle

The Root Text:

“Unsurpassable (refers to) the practice, the orientation, and complete accomplishment. They are descriptions of the (Mahayana) teachings.”

The Vehicle of Mahayana is superior to Hinayana and therefore it is called “Maha” in Sanskrit, chen-po in Tibetan, which means ‘great.’

5.1. The Unsurpassable Practices

The practices taken up in Mahayana are unequalled and therefore they are unsurpassable. They are distinctive, fast, perfect, and authentic. They can be described in terms of six features, which are the practices of the six paramitas. The six paramitas (phar-phyin-drug in Tibetan) are the ‘six transcendent actions’ of generosity, discipline, patience, diligence, concentration, and discriminating knowledge. The Regent Maitreya presented an unusual way of discussing the Mahayana practices in terms of twelve excellent features.

5.1.1.. The Twelve Excellent Features

The first feature of the Mahayana practice of the paramitas is called (1) “extremely vast.” Followers of Mahayana do not practice for the sake of temporary comfort and happiness nor do they practice for their own well-being and liberation, rather, they practice in order to be able to help all sentient beings. From that point of view, the practice is vast. Moreover, Mahayana practice is (2) enduring, i.e., it does not last for a short while but for many aeons. When the result of Buddhahood has been achieved, a Buddha’s activities for others do not stop but continue. The third feature is that it is (3) meaningful in that it is the most excellent means to help others. It is furthermore (4) inexhaustible in that it does not stop when Buddhahood has been attained, rather, enlightened activities are never concluded. The fifth feature of Mahayana practice is that it is (5) continuous and is never cut off or severed. This feature seems to be the same as the fourth, but it is slightly different. It means that the Buddha’s teachings are carried out by his disciples, who in turn teach it to their students, and so forth. In that way, the Buddha’s enlightened activities embrace everyone, and for this reason they are unceasing.

The next feature is that Mahayana practices are (6) without difficulties or hardships. This means that Mahayana practitioners are skilled and therefore are able to accumulate a vast store of wisdom and merit. For example, they are able to rejoice in others’ beneficial activities and by being generous in that way, they accumulate a tremendous amount of merit. (7) Mastery is the seventh excellent feature. Although the six paramitas are hard work for most people, this is not so for Mahayana practitioners. Since they are skilled at resting in samadhi, they master all paramitas with ease. The eighth excellent feature of Mahayana practice is that (8) it is completely held and protected by wisdom. Ordinary people might engage in the paramitas but they do not conjoin what they do with having realised the nature of reality. Bodhisattvas engage in all paramitas through the force of having realised Dharmata directly, without anything in between their wisdom and actions. In that way, their practice is embraced and pervaded with their realisation of emptiness. Those are the first eight of the twelve excellences of Mahayana practice. The following next four point out the illustrious nature of Mahayana practice in terms of the way in which practice matures disciples at the various stages and levels. Therefore, the ninth excellent feature is (9) undertaking. This means that it is the authentic way in which a practitioner engages in the vast Mahayana path right from the beginning, i.e., at the path of accumulation and at the path of joining. The tenth excellence of Mahayana practice is (10) achievement, in the sense of fruit or effect. It means that a diligent practitioner achieves or reaches the first transcendent Bodhisattva ground, which is beyond worldly grounds. The next excellent feature is called (11) “in accordance with the cause.” This means that the practice of each paramita joins a Mahayana devotee to the first Bodhisattva grounds. The twelfth feature is (12) excellent accomplishment, which is having reached the tenth ground.

5.1.2. The Ten Paramitas

The Regent Maitreya then took up a discussion of the ten paramitas that are practiced and explained the nature of each one. I will not go into this because it has more or less been discussed already.

The Root Text of the brief explanation:

“The meaning of the excellences is described in accordance with the ten paramitas.”

The Root Text of the detailed explanation:

“Generosity, discipline, patience, (joyful) exertion, concentration, supreme knowledge, dedication (method), aspiration prayers, power (strength), and primordial wisdom are the ten paramitas.”

In the detailed explanation of the ten paramitas, we learn in which way they are beneficial and therefore how each one functions. The first paramita of generosity functions in that (1) it satisfies accordingly, i.e., it satisfies recipients of generosity and causes them to rejoice in the Dharma. The second function is (2) not causing harm, in that the paramita of discipline prevents devotees from harming others. Thirdly, the function of the paramita of patience is that it makes us capable of (3) bearing harm. Then, (4) increasing qualities means that by engaging in the paramita of joyful endeavor, any good qualities that we have increase to a higher degree. The fifth function is being (5) capable of benefiting others. This means that through stability of mind we are able to benefit others with direct knowledge or magical emanations, and so forth. The next function is (6) developing perfect liberation by means of the sixth paramita of prajna (shes-rab, ‘direct, brilliant, clear knowledge’). Any action carried out with prajna surpasses temporary benefits of ordinary actions. The benefits are not just for a particular occasion, rather, our activities lead to release and liberation that is beyond samsara. The seventh paramita is given the name “dedication.” Generally, when the ten paramitas are discussed, skill or upaya (thabs, ‘method or means’) is the seventh, but the meaning is the same. Therefore, the function of the seventh paramita is dedication, which is described as (7) inexhaustible. The eighth paramita of vision is aspiration prayers (smön-lam). This paramita functions in that aspiration prayers are (8) continual engagement. The ninth paramita is stobs (‘power, strength’). It endows us with activities that are described as (9) “enjoying capacity.” The tenth paramita of exalted primordial wisdom (jnana in Sanskrit, ye-shes in Tibetan) causes activities to be non-mistaken and thus the tenth function is called (10) “bringing maturation.” This means that our activities ripen others and brings them to enter into the Dharma.

5.1.3. The Ten Dharma Activities

5.1.3.1. In Brief

The Root Text:

“Just as the Dharmas are described in the Mahayana, Bodhisattvas continuously develop the mind through the three superior knowledges.”

This section of the treatise deals with taking the excellent practices to mind, i.e., mental engagement. It is described in terms of three types of prajna. They are superior knowledge that is gained through hearing and receiving the Dharma teachings, superior knowledge that is gained by contemplating the teachings, and superior knowledge that is won by meditating them.

As for superior knowledge that is gained from hearing and receiving the Dharma teachings, generally speaking, all sentient beings without exceptions have within them the Sugatagarbha (bde-gsheg-snying-po in Tibetan, ‘the seed or essence for enlightenment,’ i.e., Buddha nature). We have that, but if we do not meet with favorable conditions, our Buddha nature will not awaken or blossom. The excellent conditions are meeting with the Buddha’s words, with the commentaries that enable us to clearly understand his teachings, and with the oral instructions that precisely show us how to practice. Having listened to the Buddha’s teachings and other instructions extensively, then our seed or potential for enlightenment will develop and grow. This is what is meant by the superior knowledge that is gained from hearing and receiving the Dharma teachings.

The second superior knowledge is gained by contemplating the teachings that we have received. This practice enables us to recognize the true nature of external and internal phenomena. By analysing and investigating the teachings again and again, we understand the truth of the teachings and thus will be able to enter the meaning. Then, the third superior knowledge that is won from meditation enables us to achieve the final fruit and manifest our true nature.

The Root Text:

“That is how to transform the meaning into perfection.”

5.1.3.2. In Detail

The short line of the detailed explanation in the Root Text:

“The ten Dharma activities should be known and held perfectly.”

First, there is a description on taking the Mahayana practice to mind by means of ten Dharma activities. The first Dharma activity is called (1) “with our own hands.” This means writing down the words and letters that contain the meaning of the scriptures taught by the Buddha. Secondly, (2) making offerings to the Three Jewels (the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, ‘the community of practitioners’). Then, (3) practicing generosity by giving poor people what they need, for example. (4) Listening and receiving the Dharma teachings. (5) Reading the texts and training in them. (6) Holding the meaning of that which we have read or heard in our mind so that it remains there. (7) Not stopping there, but explaining the meaning to others. The eighth point is (8) not forgetting the meaning. The ninth point is (9) contemplating the meaning again and again. The tenth point is (10) meditating on the meaning.

Then the special benefits of the ten Dharma activities are discussed. The Regent Maitreya stated in the Root Text:

“Since they are special, (they are inexhaustible). Since (they are) inexhaustible, (they benefit others). Since (they) benefit others, (there is) never rest.”

5.1.3.2.1. Shamata

Shamata is the Sanskrit term for zhi-gnäs in Tibetan and means ‘calm abiding meditation.’ During this practice, our mind should not be distracted and therefore should not wander. Six ways of wandering that need to be abandoned during the practice of shamata are described in the treatise. The first is (1) a natural wandering, which is due to the five sense consciousnesses. Since they are faced outwards, our eye consciousness naturally goes to whatever we see; our ear consciousness naturally goes to sounds that we hear, and so forth. Those kinds of distractions need to be abandoned. The second kind of distraction is (2) wandering to external objects, which also needs to be abandoned. Next is (3) wandering internal distractions. During practice, we turn our mind inwards and as a result qualities arise and increase. However, we might have pleasant feelings, and then it does happen that we want to meditate in order to feel comfortable and at ease. Pursuing pleasant feelings in order to taste samadhi needs to be abandoned. Fourthly, (4) wandering to signs means taking meditation to be marvellous and supreme and thus becoming attached to it. We need to also abandon attachment to our practice. Then there is (5) wandering into bad states. We might think that we are really good meditators and become proud. In that case, our meditation has become mixed with the mental affliction of pride. Mixing our meditation with afflictions also needs to be abandoned. Finally, there is (6) wandering to Hinayana. If our practice is going well, we might want to practice exclusively for our personal welfare. In that case, the scope of our practice has become very small. We need to abandon this type of distraction, too. So, when we have abandoned these six ways of wandering into distractions, our shamata practice is faultless.

The last line in the verse of the Root Text that describes shamata is: “(They) are distractions that the intellect should know.”

5.1.3.2.2. Vipassana

Vipassana is the Sanskrit term for lhag-mthng in Tibetan and means ‘special insight meditation.’ There are ten points of correct vipassana. The first is (1) being unmistaken about the letters of the words of the Buddha’s teachings. The second is (2) being unmistaken about what those letters represent. This means realising that the imagined letters of those words are mere imputations (kung-brags) that have no nature of their own. Then there is the point of being unmistaken about appearances, which are other-powered dependent phenomena (gzhän-dbang). This has two aspects, one is (3) recognizing that dependent appearances are only mind, and the other aspect is recognizing that appearances are (4) like illusions. By being unmistaken about the third aspect, we do not fall into the extreme of annihilation or nihilism, and by being unmistaken about the fourth aspect, we do not fall into the extreme of eternalism. The fifth point of correct vipassana is (5) being unmistaken about the thoroughly established nature (yongs-grub). We understand that the thoroughly established nature is free of that which is grasped and of that which grasps, of that which is fixated on and of that which fixates upon things. The sixth point of correct insight is (6) being unmistaken about the fact that Dharmata (‘suchness’) pervades Dharmadhatu (‘the limitless expanse of all phenomena’). The seventh point is (7) being unmistaken about purity and impurity, i.e., confusion. Being unmistaken about purity and impurity means understanding that Dharmata is purity and that the state of not realizing Dharmata is impurity and confusion. The next point is (8) understanding that the distinctions “pure” and “impure” are adventitious and superficial. On the one hand, knowing Dharmata means being unmistaken and not knowing Dharmata means being mistaken, nevertheless, they are dualistic concepts that are adventitious. The next point is (9) not being mistaken about samsara and thus not being mistaken about the fact that the afflictions, such as anger and belief in a self, need to be abandoned. The last point of correct vipassana is (10) not being mistaken about the necessity of cultivating and increasing good qualities and not being mistaken about nirvana.

The last line in the verse on vipassana in the Root Text is: “(They) are called ‘the ten Vajra words.’”

5.1.4.. Abandoning the Two Extremes

We have now come to the fourth aspect of unsurpassable practice. It is a discussion of the practice that is free from the extremes of existence (superimposition, externalism) and non-existence (deprecation, nihilism) and that is free from the extremes of being identical and being different.

The Root Text:

“The extremes of dualistic concepts are described in seven aspects.”

The fifth and sixth aspects of unsurpassable practice are discussed together in this treatise. The first is called “having a difference” and the second is called “being without a difference.” This means that on the first Bodhisattva ground, the practice of the paramita of generosity is particularly supreme and is accomplished. On the second Bodhisattva ground, the paramita of discipline is perfected, and so on, through the ten paramitas and ten grounds. There are differences that can be observed from that point of view. At the same time, all paramitas are practiced on all ten Bodhisattva grounds. This means that, for instance, it is not the case that the second paramita of discipline is not practiced by a Bodhisattva who is on the first ground, rather, a Bodhisattva who has reached the first ground practices all ten paramitas. So, from that point of view, there is no difference. This completes the discussion of the unsurpassable practice.

5.2. The Unsurpassable Observation

This section deals with the second of the three ways in which Mahayana is unsurpassable. Generally speaking, the Mahayana practice consists of practicing the ten paramitas. In particular, we do not think that any of the phases of practice have inherent existence. From that point of view, our practice of the paramitas is sealed, stamped, and marked by Dharmadhatu itself.

5.3. The Unsurpassable Accomplishment

The third aspect of Mahayana is called “the unsurpassable and authentic accomplishment” and is described in two phases. The first phase is called “temporary” and is a discussion of the good qualities that Bodhisattvas develop while traversing the paths to Buddhahood. The second phase is called “final” and is a discussion of that which is unsurpassable, i.e., Buddhahood. In the discussion of the second phase, the Regent Maitreya pointed out the way in which Buddhas emanate the Sambhogakaya (longs-spyöd-kyi-sku, ‘the body of enjoyment’) and manifest the Nirmanakaya (chös-kyi-sku, ‘the manifest body’) and by way of those two compassionate aspects of a Buddha present the Dharma and benefit living beings immensely. In terms of those two Kayas (sku, ‘embodiments’), Mahayana is the unsurpassable accomplishment.

The Root Text:

“That was the fifth chapter, called ‘The Unsurpassable Vehicle,’ from ‘Differentiating the Middle from the Extremes.’”

D. Concluding Words

The Root Text:

“It is very difficult to perfectly realise the treatise that differentiates the middle perfectly, the essential meaning, and the great purpose, likewise the benefits for all.

“May it dispel everything that is meaningless.”

The value of this treatise is very difficult to realise with ordinary conceptuality. It was not thought up in that manner; rather, it is an explanation of the meaning of the Buddhist scriptures by the Regent Maitreya. This treatise is meaningful and of great purpose because it benefits us and others. It illuminates everything that benefits students of Hinayana and Mahayana. It benefits disciples of every tradition. This treatise is also very clear. It dispels all wrong views and enables us to become free from afflictions that obstruct us from attaining omniscience.

The Root Text:

“This concludes ‘Differentiating the Middle from the Extremes,’ composed in verse form by the Exalted Maitreya. It was translated (into Tibetan) by the Indian Khenpos Jinamitra and Shilendrabodhi and edited in this form by the big gang of translators Yeshe De.”

====Prayers

==

Dedication:

Through this goodness, may omniscience be attained. Thereby may every mental defilement be overcome. May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara, which is troubled by waves of birth, ageing, sickness, and death.

Long Life Prayer for Thrangu Rinpoche:

Karma Lodrö, splendour of the teachings, may you remain steadfastly present, your qualities of the glorious and good Dharma spreading as far as space can go. May your activity of teaching and practice be universally victorious, and may the magnificence of this triumph blaze forth.

Long Life Prayer for H.H. the Gyalwa Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje:

Self-arising, undivided, everlasting Dharmakaya, truth body springing up as wondrous form, the Rupakaya; may the triple secret of the Karmapa rest stable in the Vajra realm, activity endless and spontaneous with glory.

Long Life Prayer for H.H. the Dalai Lama:

In the heavenly realm of Tibet, the source of all happiness and help for beings, is Tenzin Gyatso, Chenresig in person. May his life be secure for hundreds of kalpas.

Source

[[1]]