Tibetan Buddhist Meditation

Learn how to practice Tibetan Buddhist Meditation by focusing your attention on the mind.

We can begin to stabilize our minds from the beginning of our spiritual practice, while placing our chief emphasis on ethical discipline. By taking out some time each day for the practice of meditative quiescence, we become increasingly aware of how our minds function; and in the process we begin to discover how scattered our minds have been all along. Recognizing this, we may yearn to explore the potentials of the human mind that become apparent only when the awareness is still and lucid. In Buddhist practice we can choose among a wide variety of objects for stabilizing the mind. One common method in the Tibetan Buddhist meditation is to focus on an image of the Buddha.

HOW TO PRACTICE TIBETAN BUDDHIST MEDITATION

First we take a physical object, either a statue or painting of the Buddha, and gaze at it until we are very familiar with its appearance. Then we close our eyes and create a simulation of that image with our imagination. The actual practice is not the visual one – this is only a preparation – for the point is to stabilize the mind, not the eyes. When we first try to visualize the Buddha, the mental image is bound to be vague and extremely unstable. We may not even be able to get an image at all.

While the above method has many benefits, it is not ideal for everyone. For it to be effective, one must have a fairly peaceful mind, and it is helpful to have deep faith and reverence for the Buddha. For people of a devotional nature, this practice can be very inspiring, and effective at stabilizing the mind.

One’s heart is stirred by bringing the Buddha to mind with devotion, and consequently one’s enthusiasm for the meditation grows. On the other hand, if one has a very agitated mind and little faith, this and other visualization techniques may very well lead to tension and unhappiness. And these problems may increase the more one practices.

With an agitated, conceptually congested mind, the sheer effort of imagining a visualized object may be too taxing. So if one is engaging in visualization practices, especially during several sessions a day, it is important to be aware of one’s level of stress. It is important not to let it get out of hand; for if it does, instead of stabilizing the mind the practice will damage one’s nervous system.

FOCUSING ON THE BREATH

Another Tibetan Buddhist meditation method that is practiced widely, especially in the Buddhist countries of East and Southeast Asia, is focusing one’s awareness on the breath. A key attribute of this practice, as opposed to visualization of the Buddha, is that in breath awareness the object of meditation, the breath, is present without our having to imagine it.

Excitement draws the mind outward

Awareness of the breath is practiced in many different ways. Some people focus on the rise and fall of the abdomen during the in- and out- breath. Another technique is to focus on the tactile sensations, from the nostrils down to the abdomen, that are associated with the respiration. In yet another method one focuses on the sensations of the breath passing through the apertures of the nostrils and above the upper lip. All of these are valuable methods, and they can be especially useful for people with highly discursive, imaginative minds. They offer a soothing way to calm the conceptually disturbed mind.

FOCUSING ON THE MIND ITSELF

A third method of stabilizing the mind involves directing one’s awareness to the mind itself. This is the most subtle of all the techniques mentioned here, and its rewards are great. I shall elaborate on this practice in a moment, but first would like to discuss some of the themes common to all methods of stabilizing the mind.

Two facets of awareness are instrumental in all the above forms of meditative training. These are mindfulness and vigilance. Mindfulness is a mental factor that allows us to focus upon an object with continuity, without forgetting that object. So, if we are focusing on the sensations of our breath at our nostrils, mindfulness enables us to fasten our attention there continuously.

When mindfulness vanishes, the mind slips off its object like a seal off a slick rock. Vigilance is another mental factor, whose function is to check up on the quality of awareness itself. It checks to see if the meditating mind is becoming agitated and scattered, or dull and drowsy. It is the task of vigilance to guard against these extremes.

There are many inner hindrances to stabilizing the mind, but they boil down to the two extremes of excitement and laxity. Excitement is a mental factor that draws our attention away from our intended object. This hindrance is a derivative of desire. If we are meditating and suddenly find ourselves thinking about going to the refrigerator and getting a snack, we can identify this impulse as excitement born from desire. Excitement draws the mind outward. It can easily be stimulated by sound such as that of a car driving by. It compulsively latches onto the sound – a kind of mental hitchhiking – and elaborates on it with a series of images and thoughts.

First seek a relaxed, wholesome, and cheerful state of mind

When not agitated, the mind is prone to slipping off to the other extreme of laxity. This mental factor does not distract the attention outward, but brings on a sinking sensation. The mind becomes absorbed in its object without clarity, and drowsiness is to follow. At that point the object of the meditation is submerged under waves of lethargy or obliviousness.

The chief antidotes to excitement and laxity are mindfulness and vigilance, and the results of overcoming those hindrances are mental stability and clarity. These are the fruits of the practice.

Meditative stability necessarily implies an underlying ground of relaxation and serenity. The mind is peaceful, and the attention remains where we direct it for as long as we wish. Clarity refers more to the vividness of subjective awareness than to the clarity of the object. When it is present we can detect even the subtle and most fleeting qualities of our object.

For example, if we are visualizing the Buddha with clarity, he will appear in our mind’s eye in three dimensions and very lifelike. We will be able to see the color of his eyes, the individual folds in his robe. He will appear almost as clearly as if we were seeing him directly with our eyes. Such subjective clarity is instrumental in focusing on the breath as well as on the mind.

All of us have experienced moments when our attention is extremely vivid. This may occur, for example, while driving a car or motorcycle at high speed on a winding road, or when rock-climbing. But when such mental clarity is experienced it is usually combined with a high degree of tension, and the mind is neither serene nor stable. On other hand, mental stability is a common experience when we are pleasantly tired and we lie down to sleep. But in such cases there is rarely much clarity of awareness.

The challenge of meditative quiescence practice is to cultivate stability-integrated with clarity, generating an extraordinarily useful quality of awareness. To bring this about, experienced meditators have found there must be a sequence of emphases in the practice. First seek a relaxed, wholesome, and cheerful state of mind. On this basis, emphasize stability, and then finally let clarity take priority. The importance of this sequence cannot be overemphasized.

FOCUSING AWARENESS ON THE MIND

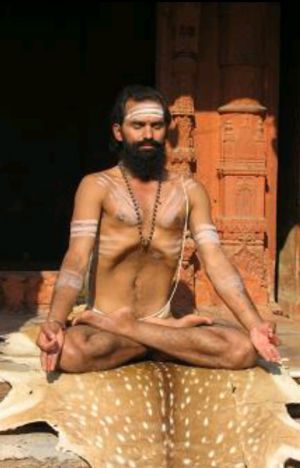

To engage in meditation on the mind, one first finds a suitable posture. It is important to sit in an erect posture, with the spine straight. It is important not to become slouched forward or to tilt to the side or backward. Throughout the meditation session one should keep the body still and relaxed.

At the outset of this or any other Buddhist practice, it is helpful to take refuge. It is also vital to cultivate a good motivation, for this will profoundly influence the nature of the practice. Finally, it is helpful to be cheerful, cherishing this wonderful opportunity to explore the nature of consciousness.

Although the main practice here is awareness of the mind, it is useful to begin with a more tangible object to calm and refine one’s awareness. Breath awareness can be perfect for this. We should cultivate a general awareness of the breath coming in and going out. During inhalation, we should simply be aware that this is taking place. During exhalation, we note that the breath is going out. Awareness is allowed to rest calmly in the present, while we breathe in a natural, unforced way.

The point here is not to speculate on this question, or to try to answer it

As we now move on to the main practice, we may follow the counsel of Tilopa, the great Indian Buddhist contemplative: “Do not indulge in thought, but watch the natural awareness.” “Natural” awareness has no shape or color, and it has no location. So how can we focus on it? What does it mean “to watch” it?

First of all, our task is to focus our attention on the mind, as opposed to the physical sense fields. One way to do this is to focus our awareness initially on a mental event, such as a thought. This thought could be anything – a word or a phrase – but it is helpful if it is one that does not stimulate either desire or aversion.

THE MIND

One possibility is the phrase: “What is the mind?” The point here is not to speculate on this question, or to try to answer it. Rather, use that thought itself as the object of awareness. Very shortly after having brought that phrase to mind, it will fade out of our consciousness. At that point we keep our awareness right where it is. We have now directed our attention on the mind, and what remains between the vanishing of one thought, and the arising of another, is simply awareness, empty and without obstruction, like space.

An analogy may be helpful. Imagine yourself as a child lying on your back, gazing up into a cloudless sky, and blowing soap bubbles through a plastic ring. As a bubble drifts up into the sky, you watch it rise, and this brings your attention into the sky. While you are looking at the bubble it pops, and you keep your attention right where the bubble had been. Your awareness now lies in empty space.

In the actual meditation practice one focuses initially on the bubble of a thought. When this thought vanishes one does not replace it with some other mental construct. Rather, one stabilizes one’s attention in natural awareness, uncontrived, without conceptual elaboration.

This practice is so subtle we may find we become tense in our efforts to do it right. Some people even find the intensity of their concentration impedes their normal respiration – they restrict their breathing for fear it will disturb the delicate equilibrium of their minds. Such tension and constricted respiration can only impair the practice and our health in general. So it is crucial that we engage in the meditation with a sense of physical and mental relaxation.

Starting from relaxation one cultivates meditative stability, resting in natural awareness without being carried away by the turbulence of thoughts or emotions. Finally, it is important to recognize that this practice is not based upon a vague sort of trance or dull absorption; rather, it calls for vivid, clear awareness.

To cultivate these three qualities of relaxation, stability, and clarity, it is usually helpful to keep the meditation sessions relatively short. The chief criterion for determining the length of one’s meditation sessions is the quality of one’s awareness during the practice. Five minutes of finely conducted meditation is worth more than an hour of low-grade conceptual chatter. Another useful criterion is one’s state of mind following meditation. The mind should be fresh, stable, and clear. If one feels exhausted and dull, one’s session was probably too long or of low quality.

PHASES OF THE PRACTICE

Once we have entered into this discipline, it may not be long before we experience short periods – perhaps up to ten seconds or longer – during which we are able to abide in a natural state of awareness, without grasping onto the thoughts and other events that arise in our consciousness. We may well find this delightfully exhilarating, and our minds may then leap upon the experience with glee. But as soon as our minds grasp in this way, the experience will fade. This can be frustrating.

The remedy is to enter into this state of awareness repeatedly. As we become familiar with it, we can then take it in stride, without expectation or anxiety. We learn to just let it be.

As the mind settles in this practice, our awareness of thoughts and other mental events is also bound to change. At times we may no longer sense ourselves thinking, yet a multitude of thoughts and images may arise as simple events.

Do not cling to these thoughts, identify with them, or try to sustain them. But also do not try to suppress them. Simply view them as spontaneous outflows of natural awareness, while centering your attention on the pure, unelaborated awareness from which they arise.

On many occasions we will find ourselves carried away by trains of thought. When we recognize this has happened, we may react with frustration, disappointment, or restlessness.

All such responses are a waste of time. If we find our minds have become agitated, the antidote is to relax more deeply. Relax away the effort that is going into sustaining our conceptual or emotional turbulence. It is best not to silence the mind with a crushing blow of our will. Instead, we may release the effort of grasping onto those mental events. Grasping arises from attachment, and the antidote is simply to let go of this attachment.

TRY TO RELAX

On other occasions we may experience mental laxity. Although the mind is not agitated, it may rest in a nebulous blankness. The antidote for this hindrance is to revitalize our awareness by paying closer attention to the practice. The “middle path” here is to invigorate our awareness without agitating it. The great Indian Buddhist contemplative Saraha says of this practice: “By releasing the tension that binds the mind, one undoubtedly brings about inner freedom.”

Patience is needed to persist in the practice

Tilopa speaks of three phases of the meditation. In the initial stages the onslaught of compulsive ideation is like a stream rushing through a narrow gorge. At this point it may seem that our mind is more out of control, more conceptually turbulent, than it was before we began meditating. But in fact, we are only now realizing how much the mind normally gushes with semiconscious thoughts.

As the mind becomes more quiescent, more stable, the stream of mental activity will become like the Ganges – a broad, quietly flowing river. In the third phase of the practice, the continuum of awareness is like the river flowing into the sea. It is at this point that one recognizes the mind’s natural serenity, vividness, transparency, and freshness.

During early stages of practice, we may experience moments of mental quiescence relatively free of conceptualization, and we may wonder whether we are now ascertaining natural awareness. Most likely we are not. Our mind at this point is probably still too gross and unclear for such a realization. Patience is needed to persist in the practice, without expectation or fear, until gradually the essential qualities of awareness become apparent. When we ascertain the simple clarity and knowing qualities of the awareness, we are on good path in the practice. We can then proceed to the attainment of meditative quiescence focused on the mind.

THE ATTAINMENT OF MEDITATIVE QUIESCENCE

In Buddhist practice the achievement of meditative quiescence is clearly defined. As a result of the practice outlined above, one eventually experiences natural awareness, and the duration of this experience gradually increases. Eventually we no longer become distracted or agitated. At this point the emphasis of the practice should be on cultivating clarity. For the mind, even after it has become well stabilized, can still easily slip into laxity.

When we finally attain meditative quiescence, we are free of even the subtle forms of excitement and laxity. The early phases of practice require considerable degrees of effort, but as we progress, more and more subtle effort suffices. Gradually the meditation becomes effortless, and we can sustain each session for hours on end.

Source

[[1]]