Influence Of Tlibetan Buddhism On The Hinterland In The Ming Dynasty

The main sects of Tibetan Buddhism (popularly; Lamaism) were originally the Nyingma (rnying-ma), Kagyu (bkav-brgyud), Kadam and Sakya (sa-skya) traditions.

Tsongkhapa founded the Gelug (dge-lugs) sect at the beginning of the 15th century. Afterwards, the Kadam sect merged into the Gelug sect. Therefore the four main sects of Tibetan Buddhism becamethe Nyingma, Kagyu, Gelug and Sakya, which continue today.

Tibetan Buddhism's eastward spread was a long process. Tibetan Buddhism began to spread from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau northward to Xixia (called Minyag in Tibetan), exerting great influence on Xixia culture. Buddhism was the most important religious belief of the Xixia people.

Xixia had a special administrative agency in charge of Buddhist affairs and monks. There were a large number of monks in Xixia at that time.

It was recorded that during on one single Buddhist meeting of making vows three thousand Dangxiang (Tangut), Chinese Han and Tibetan people renounced their domestic lives and became monks. Tibetan monks enjoyed high respect Some of them were granted the title of "State Preceptor."

Besides, Tibetan Buddhism spread northwards to the kingdoms of Liao and Jin as well. However, it had little influence on the hinterland at that time.

It was in 1247 that Tibetan Buddhism spread to Mongolia when Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen (1182-1251) had an interview with the Mongolian Prince Godan at Liangzhou (now Wuwei of Gansu Province).

Since then Sakya sect's leader Phagpa (1235-1280) had followed Kublai Khan and was promoted to the post of Imperial Tutor. The Kagyu tradition, another main sect of Tibetan Buddhism, also had contacts with Mongolia when Kublai Khan made a southward military expedition. After the Mongolian leader, who was Buddhist, conquered and became master of the Central Plains he imported leaders of Tibetan Buddhism.

The central government of the Yuan Dynasty established the Zongzhi (General) Council, a body that handled Buddhist affairs for the whole nation and the local administration of the Tibetan areas, in 1264.

The council was renamed as Xuanzheng in 1288.

The Yan Emperor put the State Preceptor Phagpa in charge of the newly established council.

In the autumn of 1264, Kublai Khan took Tantra vows of Tibetan Buddhism from the State Preceptor Phagpa. This indicated that Kublai Khan officially devoted himself to Tibetan Buddhism. Following his example, Mongolian queens and princes also took Buddhist vows. Worshipping Tibetan Buddhism became a fashion for the Mongolian aristocrats of the Yuan court.

Phagpa worked out an alphabetical scheme of writing for the Mongolian language in 1269.

In recognition of his service, the Yuan Emperor granted him additional titles as "Imperial Tutor of the Yuan Dynasty" and "Great Treasure Prince of Dharma."

In 1271 Kublai moved his capital to Beijing.

After the Yuan Dynasty was founded, Kublai gave more support to Tibetan Buddhism, which was then represented by the Sakya sect.

He built Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Dadu (Beiling), Zhongdu (Kaiping) and Shangdu (Duolun), and financially supported Phagpa in holding grand religious performances at the capital city.

Phagpa's followers and the monks of other sects of Tibetan Buddhism took the opportunity to propagate the doctrines of Tibetan Buddhism. This made Tibetan Buddhism spread very fast in Mongolia and the central plains.

The Yuan court's respect for eminent monks of Tibetan Buddhism reached its zenith. According to Yuan Shi (History of the Yuan Dynasty), "The orders of the Imperial Tutor are regarded as highly as those of the Yuan Emperor in Tibetan areas.

In a hundred years the imperial court paid the highest respect to the Imperial Tutor. Even the Emperor and his concubines and princes knelt down before him for taking religious vows.

Whenever a court meeting was held for high-ranking officials to have an audience with the Emperor there would be a special seat in the court for the Imperial Tutor. When a new emperor came to the throne, he would grant the Tutor a decree of praise as well as a seal of authority" 1

Besides, the flourishing development of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongulia and the central plains during the Yuan Dynasty was also indicated by a large number of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries built and the frequent Buddhist ceremonies held there. The Yuan imperial family and aristocrats in the capital city built more than a dozen Tibetan-styled Buddhist temples and monasteries.

The main ones were:

Da-hu-guo-ren-wang-si (Monastery of the Great Protector of Benevolent King),

Da-sheng-wan-an-si (crhe Great Holy Peace Temple),

Xing-jiao-si (Flourishing Buddhism Temple),

[[Da-chong-guo-si] ([[Great {Worship State Temple]]),

Da-cheng-hua-pu-qing-si (Monastery of Universal Happiness),

Da-tian-shou-wan-ning-si (Monastery of Great Heavenly Longevity and Great Peace),

Da-chong-en-fu-yuan-si (Monastery of Great Blessedness),

Da-yong-an-si (Temple of Everlasting Peace) Da-cheng-tian-hu-sheng-si (The [[Holy Temple]under Heavenly Protection]]),

Da-tian-yuan-yan-shou-si (Temple of Longesvity),

Da-yong-fu-si (Temple of Everlasting Blessing),

Shou-an-shan-si (Temple of Longevity and Peace) and others.

The construction of these monasteries and frequent performances of religious ceremonies consumed a large amount of money and materials each year.

I. Ming's policy of granting offices and titles to Tibetan monks and Tibetan Buddhist monks coming eastward

After Zhu Yuanzhang founded the Ming Dynasy, he and other Ming emperors, like the Yuan emperors, pursued a policy of patronizing and using Tibetan Buddhism in governing Tibet.

The difference was that instead of keeping an eye on the Sakya sect alone, as was the practice of Yuan, the Ming conferred honorific titles on the leaders of all the influential Sects of Tibetan Buddhism.

Ming's policy was in accordance with the Tibetan political situation in which various Buddhist sects each acted independently.

The titles conferred were "Prince of Dharma," "Prince," "the Buddha Son in the West Pure-land," "Great State Preceptor of Initiation" "State Preceptor of Initiation" and "Chan Master."

Leaders of almost all sects of Tibetan Buddhism were granted an honorific title. All Tibetan religious leaders with honorific titles paid tributes at the capital.

They presented local products as tribute. Imperial bestowals in return usually far exceeded the tributes by several dozens of times. Under such historical circumstances in the Ming Dynasty a large number of Tibetan monks went out of the isolated monasteries and stepped onto the wide political stage.

For generation after generation they spared no effort to seek the honorific titles, rich bestowals and courteous treatment from the imperial court. A period of nearly three hundred years of the Ming Dynasty witnessed endless tribute-paying groups of Tibetan monks going to and fro on the road between Tibet and the capital city.

In the Ming Dynasty, Tibetan monks started to go to the hinterland in the early Hongwu's reign (1368-1399). They were permitted by the imperial court to visit famous Buddhist spots and recruit disciples in the hinterland. Therefore many Tibetan monks lived in the hinterland for a long time, and even built monasteries there for themselves.

Ming Sbi Lu (Documentary Records of the Ming Dynasty) pointed out that in the 18th year of the Hongwu's reign, "Jiming Monastery was built on Mt.

Jiming in memory of monk Bao Gong of the Liang Dynasty, with monk De Xuan as its first abbot.

When De Xuan died the successor was Dao Ben.

In the early years of the Hongwu's reign of the Ming Dynasty Tibetan monk Sanggye Gyaltsen, who had been appointed as a Right Buddhist Rectifier, came to the mountain.

A house was built for him to west of the Jiming monastery."2 Enjoying preferential treatment from the Ming emperors, Tibetan monks had monasteries built for them in the capital city and even in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces.

Those with the titles of "Prince of Dharma," "Great State Preceptor, Buddha-son in the West Pure Land" and "State Preceptor of Initiation" enjoyed much higher treatment. They went into and out of the imperial court in a proud air.

The Ming court moved its capital city from Nanjing to Beijing in the Yongle"s reign (1403-1425). The Ming Emperor Yongle attached even more importance to Tibetan monks than the Emperor Hongwu.

As Tibetan Buddhism had exerted greater impact than Chinese Buddhism did on the Yuan's capital city of Beijing in the Yuan Dynasty, the Ming followed the Yuan's inheritance in embracing Tibetan Buddhism.

According to a rough statistic, Beijing had a dozen Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Ming Dynasty, of which:

Da-long-shan-hu-guo-si (Great Merits Monastery for Protecting the Country),

Da neng-ren-si (Great Be-nevolence Monastery),

Da-ci-en-si (Great Monastery of Compassion and Grace),

Zhen-jue-si (Monastery of True Enlightenment) and

Xing-jiao-si (Xingjiao Monastery) were well known.

Regarding the number of Tibetan monks in Beijing in the Ming Dynasty, there were no accurate statistics. In a word, the number was great.

The Ming imperial court patronized the Tibetan monks in Beijing. This patronage required such a great amount of financial expenditure that the Ming imperial court once could not afford it.

When the Ming Emperor Yingzong came to the throne, Hu Ying, minister of the Board of Rites, suggested to the Emperor that the number of Tibetan monks be reduced by 691.

Hu Ying's suggestion was accepted.

In the fifth month of the first year of the Zhengtong's reign (1436) of the Ming Dynasty, the number of monks of Ci-en, Long-shan, Neng-ren and Bao-qing monasteries was reduced by 450."3

From the historical record we can see that the number of Tibetan monks was reduced by 1, 100 in only two years from the tenth year (1435) of the Xuande's reign to the first year (1436) of the Zhengtong's reign. According to a conservative estimation, the total number of Tibetan monks in Beijing was not lower than 2, 000 at that time.

There were so many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and monks in Beijing that they constituted a part of the culture of the capital city during the Ming Dynasty. Some Tibetan Buddhist rites and customs prevailed at the royal court and also among the people.

II. Tibetan Buddhism's impacts on the imperial court

1. The Ming Emperor Yongle (Chengzu) and Tibetan Buddhism

It was probably in the Yongle's reign that the Ming imperial court began to worship Tibetan Buddhism.

The Ming Emperor Hongwu (Zhu Yuanzhang, also called Taizu) had been a monk for eight years before he founded the Ming Dynasty. This unusual expertence led him to adopt the policy of granting new offices and titles to Tibetan monks in accordance with the then political situation.

He knew very well the role of eminent Tibetan monks amongst the Tibetan people, so he tried his best to draw the high-ranking Lamaist monks over to his side by inviting them to visit the imperial court and give them preferential treatment. He did it for political purposes though he himself did not believe in Buddhism.

However, the Ming Emperor Yongle (Zhu Li, also called Chengzu) in the Ynnde's reign devoted himself to Buddhism. The "Xi yu Zhuan" (Records of the Western Regions) in Ming Sbi (History of Ming Dynasty) mentioned it in an ambiguous sentence: "He also believed in this religion." However, Ming-shi-lu (Documentary Records of the Ming Dynasty) did not say a word about it.

It was in the Yongle's reign that the honorific title of "DharHia Lord" began to be conferred on eminent Tibetan monks. A Feast for Wise Men (mkbas-pavi-dgav-ston), a Tibetan historical book, recorded the following invitation letter, which the Ming Emperor Yongle, (Chengzu or Zhu Li) sent to Deshin Shekpa (de-bzhin gshegs-pa), the fifth "black hat" Karmapa:

An imperial decree for inviting Karmapa

You, spiritual teacher, have a good knowledge of Buddha's teachings. All sentient beings in the west get benefit from you. All living beings worship you as if you were the Buddha reappearing in the world. Without your great achievements in obtaining wisdom and merits, how could you bring benefits to all living beings? When I lived in the north I heard of your name and was anxious to see you.

Now I have come to the throne and the Central Plains are in peace. I have long cherished a wish to overcome ignorance and to awaken to the truth in order to help all the living with meritorious work. The Buddha helped all living beings with his mercy. You have the same mercy as the Buddha in your achievements in practicing Buddhism. I hope you will come to the Central Plains to propagate the Buddha's teachings.

For our country's benefit and my long cherished wish, I will learn Buddhism from you when you come. Be sure to come. The late Emperor who founded the dynasty in the Central Plains worshipped Buddha's teachings with sincerity. He and his queen have both passed away. I have cherished the wish to repay their favors shown to me. So, as a master with great achievements in Buddhism, it is hoped you will come to hold liberation rituals for the deceased. Now I send Hou Xian, my eunuch of rites, to invite you with this letter.

I hope you'll accept my invitation and come as soon as possible. Together with the letter are the following gifts to you: three big silver ingots in a total of 150 taels, ten bolts of silk and ten boits of satin, a piece of sandalwood, ten jins of white incense, one jin of Suhe incense and 150 jins of white tea.

This decree was written at the Grand Palace on the 18th day of the second month in the first year (1403) of Yongle period. 4The Ming Emperor Yongle (Chengzu) took the lead in worshipping Tibetan Buddhism. His subordinates followed his example. So the whole court was under the influence of a flourishing Tibetan Buddhism.

Ac-cording to a historical record of the Ming Dynasty, Tibetan Buddhist statues were worshipped in the Yinghua, Longde and Qin'an halls of the imperial palace.

In each of the halIs eunuchs were sent to take charge of serving them with incense and candles. On the Emperor's birthday, New Year's Day and Ullambana Day, Buddhist rituals would be held at the sutra-printing house and a Tibetan Buddhist religious dance would be performed at the Longde Hall. 5 It was then a common practice that Tibetan monks were invited to chant sutras and hold religious rituals in the imperial palace.

2. Zheng He and Tibetan Buddhism

Most of the attendants in charge of religious rituals at the palace were eunuchs. So many Ming eunuchs believed in Tibetan Buddhism. Some of them such as Hou Xian, Gu Dayong, Li Tong and Liu Jin were well-known eunuch Buddhist believers, but some others were not known to the people, such as Zheng He, the Emperor's most trusted eunuch.

People know only that Zheng He sailed to the west seven times, but they do not know he was a devoted follower of Tibetan Buddhism.

According to Ming Shi (History of the Ming Dynasty), Zheng He was called "San-bao Tai-jian ([三保]], Three-protections Eunuch)." "San-bao" was neither his personal name nor an honorific title. However, in other historical books of the Ming Dynasty, the title was written as "San-bao" (三宝, meaning "the Three Precious Jewels" in Chinese).

In Buddhism, the "Three Precious Jewels" denotes "Buddha, Dharma and Sangha (community of monks)." The Buddha preached Dharma and monks preserved Dharma to save all beings.

All Buddhists should surrender themselves to the Three Precious Jewels. Tibetan Buddhism attached great importance to the "Three Precious Jewels" (called "dkon-mchog-gsum" in Tibetan).

In Tibetan society both lay and religious people take the Three Precious Jewels as witness when they make vows.

Zheng He as a believer of Tibetan Buddhism also expressed his sincere thanks to the "Three Precious Ones" in his prayers printed in sutras.

So the "San-bao" for Zheng He in the Ming Shi undoubtedly means the "[[Three Precious] Jewels]]." 图一

The record concerning Zheng He's belief in Buddhism can be found in the 'Preface to Rules of Liberation for Upasaka', vo1. 7 (which was printed in the early period of the Ming Dynasty) as follows:

"Zheng He was a eunuch of the Ming imperial court. He believed in Buddhism. His religious name was Sonam Drashi, which means‘blessedness and auspiciousness.' Fortunately, he lived in the prosperous period of the Ming Dynasty.

Thanks to the protection of Heaven and Earth and the Emperor's favours, he was able to sail to the west under an escort of troops for public affairs several times.

All went well for his trips. He always cherished the wish to repay these favours. He gave alms for the printing of Tripitaka Sutra so the sutra would be chanted widely.

He wished the Emperor's rule would last for eternity. Every-where he went on the Emperor's errands, he would kowtow to the Emperor for his favour. He wished the Emperor would always enjoyed good luck, happy life and longevity. He wished everyone in Buddhist circles good progress.

Zheng He had ten sets of Tripitaka Sutra printed at his expense. One set was printed on the 11th day of the 3rd month of the 4th year of Xuande period of the Ming Dynasty and it was placed and worshipped in the Foku Monastery at Mt. Niushou.

The second one printed on the 11th day of the 3rd month of the 5th year of the Xuande reign was worshipped in Jiming Monastery.

The third one printed on the 11th day of the 3rd month of the 5th year of the Xuande reign was in Beijing Huanghou (Queen) Monastery. The fourth one printed on the 11th day of the 10th month of the 22nd year of the Yongle reign was in Jinghai Monastery. The fifth one printed on an auspicious day of the fifth month of the 18th year of the Yongle reign was in Jinshan Monastery of Zhenjiang.

The sixth one printed on the 11th day of the 3rd month of the 13th year of the Yongle reign was in Sanfengta Monastery at Mt. Nan-shan of Fujian. The seventh one printed on an auspicious day of the winter of the 9th year of the Yongle reign was in the Vairochana Hall of the Tianjie Monastery. The eighth one printed on the 11th day of the 3rd month of the 8th year of the Yongle reign was in the Wuhua Monastery of Yunnan. The ninth one printed on the 11th day of the 5th year of the Yongle reign of the Ming Dynasty was in the Linggu Monastery." 6

In his Gu Dong Suo Ji (Random Notes on Antiques) the above record was cited by Mr. Deny Zhicheng.

The ten sets of sutras printed by Zheng He are lost but Mr. Deng said: "In the spring of ding-hai year Mr. Li Xingnan of Jixian County happened to get the edition of the Rules of Liberation for Upasaka, vo1. 7, which has a postscript…

In the postscript, before each Chinese character "fo" (Buddha), "seng" (sacred) and "huang" (emperor) there is a space, and each year num-bet and monastery name is put at the beginning of the next line. Zheng He sailed to the west seven times. The dates of the printing in the cited record are mostly before his sailing.

Zheng He was a native of Yunnan, so he naturally also donated a set of Tibetan Tripitaka to the Wuhua Monastery of Yunnan. The Wuhua Monastery and Huaguo Monastery are on Mt. Wuhua in the capital city of Yunnan but now they have long been in ruins." The ding-hai year of the Chinese calendar was 1947.

It was true that Mr. Deng saw the postscript and had it copied. However, according to the record Zheng He printed ten sets of Tibetan Tripitaka, but only nine were mentioned above. I think one was omitted by mistake.

There is another record, which was earlier than the one above. This record was written by monk Dao Yan, Right Buddhist Patriarch of the Central Buddhist Registry in the Central Government of the Ming Dynasty. On the 23rd day of the eighth month in autumn of kui-wei year or the first year of Yongle reign (1403), monk Dao Yan wrote a preface to the reprinted sutra Marichi Deva Dharani. He said in the Preface:

Zheng He is a Mahayana Buddhist; his religious name is Fushan. He had sutras printed by the Bureau of Works with his donation. His merits are too big to be expressed with words. One day he came to ask me to write a preface for the printed sutra. So I did." 7

Dao Yan was none other than Yao Guangxiao, an eminent monk of the Ming Dynasty. Yao became a monk at the age of 14 His religious name was Dao Yan. Though he was a monk, it was he who suggested Prince Yan to seize the throne by military force. When Prince Yan came to the throne as Ming Emperor Yongle (Chengzu), he trusted Dao Yan very much. Dao Yan was also very familiar with Zheng He. From Dao Yan's words about Zheng He it can be seen that the relations between them were unusual.

More detailed records have not been found till now. However, the above two records are enough to prove that Zheng He believed in Buddhism. He claimed him-self as "a Buddhist of the Great Ming, religiously named as 'Sonam Drashi' meaning auspiciousness." According to Dao Yan' preface, Zheng was a Mahayana Buddhist.

Zheng He donated a large sum of money to the printing of ten sets of sutras. If each set consisted of 635 hans, the ten sets should have cost as much as 6, 350 hans. Except the ten sets of Tripitaka sutras he printed and donated to ten monasteries, there were copies of Marichi Deva Dharani also printed by him.

He took on his shoulder the important responsibility of leading the expedition of official ships sailing to the west several times. The Emperor also entrusted him with the task of supervising the construction of Great Bao-en Monastery.

Generally, only a Buddhist could be a supervisor of a monastery construction. All this proved that Zheng He was a Buddhist. Otherwise it cannot be explained why he did those things.

I think, it was Zheng He's personal experience and the then social background that made him believe in Buddhism. Zheng He left home at the age of 10 with little knowledge of the world. 8

Historical books of the Ming Dynasty did not tell us when he became a eunuch of Ming Emperor Yongle. In a word, he was very young at that time. The Ming Emperor Yongle's main advisor was monk Dao Yan.

This showed that the Emperor had unusual relations with Buddhism. The Emperor's religious policies toward Tibetan areas also show his close relationship with Buddhism.

Although the official historical books of the Ming court ignored the Emperor's belief in Buddhism, yet they still made a few critical remarks on his attitude to Tibetan monks.

One of the Ming materials says: "For the purpose of civilizing and pacifying the people of the borderland, Emperor Taizu invited a few Tibetan monks and conferred honorific titles of ‘State Preceptor' and 'Great State Preceptor' on four or five of them only. However, Emperor Yongle not only patronized the monks but also believed in their religion. He granted honorific titles on many more Tibetan monks.

There were:

five monks with the title of ‘Propagation Prince of Persuasion',

two with '[[Prince}of Dharma]]',

two with ‘the Buddha Son in the West Pure-land',

nine with ‘Great State Preceptor of Initiation' and

eighteen with ‘State Preceptor of Initiation',

in addition to numerous monks with the titles of‘Master of initiation' and ‘Monk official'.

The roads were so crowded with Tibetan monks that the postal delivery and even government affairs were badly influenced. Officials and common people were annoyed, but the Emperor paid no attention to it." 9

Ming Shi ([[History of the {Ming Dynasty]]) said that Emperor Yongle "worshipped their religion," which meant that the Ming Emperor Yongle not only made use of Tibetan Buddhism but also believed in it. The Emperor's attendants were, of course, no exception.

A person of the Ming said in his notes, "most of the Ming eunuchs believed in the doctrine of cause-effect and worshipped Buddhism." 10 Surrounded by Buddhist atmosphere, Zheng He naturally converted from Islam to Buddhism.

Zheng He claimed himself as a Mahayana Buddhist. His religious name was Sonam Drashi, a common Tibetan name meaning auspiciousness. Zheng He took it as his Buddhist name. This showed that Zheng He believed in Tibetan Buddhism.

As Dao Yan wrote the preface to Marichi Deva Dharani in the first year of Yongle period of Ming (1403), Zheng He converted to Tibetan Buddhism and took Bodhisattva vows.

This must have been before the first year of the Yongle's reign. Owing to lack of data we do not know when he was ordained or who was his religious tutor.

According to the time clues we can see Tibetan Buddhism had exerted a big influence on the capital city long before the first year of the Yongle's reign. The influence was so big that eunuchs converted to it one after another. A historicalbook says:

Tibetan monks won the Emperor's favour with their secret religion (Tantra, or the esoteric sect). The utensils for them to use in daily life were like those for the princes.

Whenever they went Out they sat in sedans. Before the sedans were guards holding golden ceremonial weapons. Seeing their sedans coming, officials and aristocrats all got out of the way.

When they were summoned to chant sutra in the imperial palace, flowers and grains were scattered on the road they were passing. Abundant food and drink were provided daily to them by the imperial kitchen. Several thousand Tibetan monks enjoyed free high quality meals and clothes.

The eunuchs, whenever met the monks, would kneel down before them anti the monks would sit and receive their salute. There were many dozens of honorific titles for the Tibetan monks." 11

The historical record told us that eunuchs paid great respect to Tibetan monks. Having opportunities to be close to monks, eunuchs naturally treated them as religious tutors and took Buddhist vows before them.

The Tibetan monks came from far-away snow lands. With a cultural tradition different from that of the hinterland, Tibetan monks developed a set of specific religious rituals.

Particularly, the rituals of Tantra Tibetan Buddhism were complex, mysterious and attractive. At that time the Ming Emperor, officials and common people all worshipped Tibetan Buddhism. Following their example Zheng He naturally converted to Tibetan Buddhism. This was not a strange thing.

Perhaps the practice of taking the Mahayana vows and having a Tibetan religious name was a fashion at that time.

3. Ming Emperor Wuzong and Tibetan Boddhism.

The preferential treatment given to Tibetan monks by the Ming imperial court reached its climax in the period of the Ming Emperor Wuzong.

Soon after coming to the throne, the Ming Emperor Wuzong was interested in Tibetan Buddhism to the point of obsession. He built Yan-shou (Longevity) Temple in the western part of the imperial palace.

Tibetan mantra-adept or master of tantra took their residence there.

Wuzong invited Tibetan monk Rinchen Drup to the capital city and conferred on him the title of "Great State Preceptor of Initiation." The Emperor granted the late Emperor Xiaozong's personal Buddhist teacher the title of "State Preceptor."

Then he conferred on Tengye Odser, a Tibetan envoy, the title of "Great Virtue Prince of Dharma." Most of the Tibetan monks in the capital city of Beijing were granted the titles of "Son of Buddha," "State Preceptor" and "Buddhist Master," and were appointed monk officials such as Right and Left [[Jue-yi] (Buddhist Rectifier), Right and Left Zheng-yi (Buddhist Patriarch) and Du-gang of "Seng-lu-si" (Central Buddhist Registry).

The most influential event was the construction of Baofang (House of Lust) by the Emperor Wuzong in his palace. The Baofang is a house where the Emperor and Tibetan monks practiced Tantrism, the secret sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Baofang was a storied building with secret rooms on either side. It had more than two hundred rooms.

The Emperor appointed Liu Yun, a eunuch who had been dismissed, as chief manager of Baofang. Rinchen Drup and other Tibetan monks were often invited to chant sutra and practice Tantric Buddhism in Baofang. Emperor Wuzong learnt the Tibetan language and often wore monk clothes.

He even called himself "Dharma Lord of Great Celebration" and made for himself a golden seal with the inscription of "Dharma Lord of Great Celebration, Buddha of Enlightenment and Perfection in Pure-land," so that the monk seal and emperor's official seal stood side by side for a long time.

Wuzong issued three hundred thousand copies of monk certificates of ordination to Tibetan monks in order to spread Tibetan Buddhism.

Wuzong often chanted sutras together with Tibetan monks and eunuchs. He had his palace maids' hair Cut as nuns and gave them sermons on Buddhism.

The Emperor several times sent eunuchs to Tibet to invite Tibetan monks to the capital city of Beijing According to Wu-Zong-Shi-Lu (Documentary Records of Wuzong), the Emperor knew Tibetan and Sanskrit very well.

He made deep research into Buddhist sutras and scriptures and especially the doctrines of various Tibetan Buddhist schools. The officials who worshipped Confucianism were dissatisfied with Wuzong over his devotion to Tibetan Tantra. They even criticized him for it on the risk of their lives.

III. Tibetan Buddhism's influence on Chinese Buddhism in the hinterland

During the Kaiyuan reign (713-741) of the Tang Dynasty, Shubhakarasimha, Vajramati and Amogha made the first introduction of the Garbhadhatu and Vajradhatu of Tantrism to the hinterland.

They founded the Esoteric Sect, or Tantrism of Chinese Buddhism in the hinterland.

According to Tantrism, the Buddha and all living beings in the world are made of "six elements;

The former five elements are phenomena, the actual or phenomenal states as conceived, and they belong to the Garbhadhatu (reason and cause). The element of "mind" is of mental state and it belongs to the Vajradhatu (wisdom and fruit). Phenomena and mind are the same.

The Garbhadhatu and Vajradhatu are identical.

People who practice the empowered three mysteries (the Buddha's body, mouth and mind), that is, do Buddha's hand-seal, read Buddha's words and contemplate the Buddha, can make the three karmas of body, mouth and mind purified and identical with the Buddha's mind, mouth and mind.

As a result, the people can enter the Buddhahood.

The Tantrism had very complex religious rituals. There were strict rules on making a mandala (an open altar), offering sacrifice to gods, chanting prayers, and holding initiation ceremony.

After two generations Chinese Tantrism declined. One branch of the Chinese Tantrism was introduced. into Japan and became the Japanese Shingon School (1it School of the True Word) or the Eastern Esoteric Sect (which also developed several sub-sects).

After Tibetan Tantrism was introduced to the hinterland in the Yuan Dynasty, it flourished there.

One of the cardinal events in the history of Chinese Buddhism was the collation of Tibetan and Chinese scriptures of Buddhist Tantrism and the publishing of Zhiyuan-fabao-kantong-lu (A General Catalogue of Collated Buddhist Classics of the Zhiyuan Period) in the Yuan Dynasty.

A detailed comparison was done to see whether there were any missing sutra-names in the Chinese and the Tibetan editions, to find differences between the two editions in the number of volumes, in translation, classification and sutra names, and to fill in the Sanskrit sutra titles missing in the Chinese Tantric scriptures according to its Tibetan counterpart.

This work of collation showed "the Tibetan and Chinese editions had slight differences in word expressions but had the same doctrines," just as Jing Fu said in his Preface to the book.

Buddhist scripture translation activities in the hinterland in the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties were mainly the translation of Tantric sutras from Tibetan to Chinese.

Among the Buddhist circles who engaged in the translation work were some eminent Chinese and Tibetan monks who knew both the Chinese and Tibetan languages well, such as Zhi Guang, a famous Chinese monk in the early Ming Dynasty, and Palden Drashi, a Tibetan monk with the title of "Great Wisdom Dharma Lord."

A part of the Tibetan Buddhist scriptures of the Zhengtong reign, in the Ming Dynasty, have been preserved at the Yunju Monastery of Fangshan County of Beijing.

They consist of a thou-sand odd volumes of five kinds of Tibetan Buddhist scriptures of the Ming Zhengtong period, of which the most important one is Sheng-sheng-hui-dao-bi-an-gong-de-bao-ji-ji (Gatha of Merits of Sacred Wisdom in Going to the Pure Land).

These Tibetan Buddhist scriptures published in the Ming Dynasty are now rare in Tibetan areas as well as in the hinterland and there-fore they are very precious. The Sheng-sheng-hui-dao-bi-an-gong-de-bao-ji-ji was edited by Pahlen Drashi, based on a Tibetan-Xixia edition of the scripture printed in Xixia.

Many Chinese monks in the hinterlands knew Tibetan Buddhist Tantric rituals and scriptures well. Among them were three eminent Chinese monks who were sent by the Emperor to Tibet in the Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty.

In historical records of official envoys dispatched by the Ming government to pacify Tibet, only Xu Yunde, vice-director of Shaanxi province, was mentioned. He was dispatched as an envoy to pacify all the tribes of Tibet.

In fact, this difficult task could not fulfilled by only one envoy. Historical books over-looked three eminent monks who made great contributions to the unification of China in the early Ming Dynasty. They were Zong Le, Ke Xin and Zhi Guang, three eminent Chinese monks at the turn of the Yuan and the Ming dynasties. The Ming Emperor in the Hongwu reign created the use of monks in policy making for pacifying Tibet.

For an account of the monk-envoys it is necessary to say something about Da-tian-jie Monastery of Jinling (the present-day Nanjing).

In the Yuan Dynasty Zoug-zhi (General) Council, which was renamed Xuan-zheng (Political Council, was responsible for Tibetan political and religious affairs.

When the Ming Dynasty was founded. The council was abolished.

The Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang made new policies toward the administration of political and religious affairs in Tibetan areas.

The affairs were so many and complex that an ordinary administrative department such as Department of Rites could not handle them and a special agency had to be established for them. So the Ming Emperor appointed the Da-tian-jie Monastery of Jinling to the post of special agency to meet the task.

The Tian-jie Monastery of Jinling was built in the Yuan Dynasty. It was originally the Yuan Emperor Wenzong's) private mansion. The Emperor changed it into a monastery in the second year of the Tianli period (1329) of the Yuan Dynasty.

The monastery was named "Da-long-xiang-ji-qing-si," and its first abbot was eminent monk Guang Zhi, who was Zong Le's tu-tor in the late Yuan Dynasty.

In the 3rd month of the 16th year of the Zhizheng period of the Yuan Dynasy, Zhu Yuanzhang captured Jiqing (now Nanjing) and stationed his troops at the Da-long-xiang-ji-qing-si monastery.

The monks of the monastery fled. Its abbot Hui Tan tried to defect to the new dynasty. Zhu Yuanzhang renamed the monastery as Da-tian-jie-si monastery and appointed Hui Tan its abbot. 12

"Supported by the Ming Emperor Taizu, the monastery became famous for a long time. One history book said, when the monastery held a religious meeting, Hui Tan would preside over it and the Emperor would attend it and give a donation to the monastery.

The monastery was then so crowded that there was no place even for the monks coming from afar to attend it. 13 Over the gate of the monastery was a board with Chinese characters "Tian-xia-di-yi-chan-lin" (the most important monastery in the world) written by the Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang.

The importance of Tian-jie-si monastery was that it concurrently supervised the whole nation's religious affairs. In the first month of the first year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty, the Ming Emperor Taizu established Shah Shi (Benevolence to the world) Council in the monastery and appointed Hui Tan as its director in charge of religious affairs. 14 Hui Tan was granted the title of "Great Buddhist Master of Benevenence to the World, State and Buddhism" and was appointed a monk official of the second rank.

An imperial edict was issued for the appointment and a purple official robe was given to him. The Shan Shi Council was the first monk official agency in the Ming Dynasty.

The Ming Dynasty initiated the use of "Shan Shi" as a title of a monk official agency. "Shan Shi" means that people should do good things for the world, just as Song Lian said: "Doing good things is a principle for entering the Buddhahood."15

Not long after the Shan Shi Council was established Hui Tan fell sick. He recovered in the summer of the 3rd year of Hongwu period. Then the Emperor dispatched him to the Western Regions. "In the autumn of the 4th year of the Hongwu reign he came to Sheng-ha-la kingdom, where he announced the Emperor's power and virtue.

The king had him stay in a monastery and treated him as a Buddhist master." 16 In the 9th month of the same year the envoy Hui Tan died in the West Regions. Unfortunately, he was not able to come back to make a report on his mission to the Emperor personally.

Ke Xin and Zong Le, who were dispatched to Ti-betan areas as envoys in the Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty, were monks of the Da-tian-jie-si monastery.

1. Ke Xin as an envoy to Tibet.

There were few records concerning Ke Xin. Da-ming-gao-seng-zhuan (Biographies of Eminent Monks of the Ming Dynasty) and Xin-xu-gao-seng-zhuan (A New Sequel to Biographies of Eminent Monks) had no biography of Ke Xin. In his article "A Study of Monk Ke Xin as an Envoy to Tibet in the Early Ming Dvnasty," 17 Mr. Deng Ruiling cited Ke Xin's three poems and a brief record of his life from the Lie-chao-shi-ji (A Collection of Poems of Previous Dynasties) edited by Qian Qianyi. It says,

"Ke Xin, whose other name was Zhong Ming, was a native of Fanyang. He was the 9th generation descendent of She Xianggong, a minister of the Song Dynasty.

At first he Sought the way of imperial examinations. When the Yuan imperial court abolished the rank of "jin-shi" (the successful candidates for the highest imperial examinations), he turned to engage in the study of Buddhism. He knew the scriptures of Buddhism and other religions well, and was good at the ancient Chinese prose.

He traveled to Mt. Lushan and famous rivers, and visited the relic sites of the former six dynasties at Jinling. He served as a secretary for seven years in the monastery rebuilt from Yuan Emperor Wenzong's private mansion.

When a war broke out he went to Suzhou and Hangzhou. He was abbot of Huiri monastery of Changshu and afterwards, of Ziqing monastery in Pingjiang. In the Gengwu year of the Hongwu reign he was dispatched by the Emperor to the West Regions to pacify Tubo."

The "monastery rebuilt from Yuan Emperor Wenzong's private mansion" as mentioned above was the Ji-qing-da-long-xiang-si monastery of the Yuan dynasty, and also the Da-tian-jie-si monastery of the Ming Dynasty. Ke Xin served as a secretary in the Ji-qing-da-long-xiang-si monastery for seven years until the end of Yuan Dynasty.

At that time Xiao Yin was the abbot of the monastery. According to the Xing-xu-gao-seng-zhuan, Xiao Yin had ten disciples, among whom Ke Xin was the youngest. Xiao Yin was Ke Xin's tutor, so Ke Xin and Zong Le were both served by one and the same tutor.

In the 3rd year of the Hongwu's reign (1370) the Emperor dispatched Ke Xin to Tibetan areas. It was recorded that in the 6th month of the 3rd year of the Hongwu's reign three monks, including Ke Xin, were sent to the west Regions to pacify Tubo and they were ask-ed to make a map of the places they passed through. 18

Owing to a lack of sufficient data we do not know where he went or when he returned to the capital or anything else about his mission.

2. Zong Le as an envoy to Tibet.

According to the Da-ming-gao-seng-zhuan (Biographies of Eminent Monks of Ming Dynasty), Xin-xu-gao-seng-zhuan (A New Sequel to Biographies of Eminent Monks) and Bu-xu-gao-seng-zhuan9 (A Further Sequel to Biographies of Eminent Monks), Zong Le was a native of Linhai (now Linhai county of Zhejiang province). He was surnamed Zhou and named Jitan, also named Quanshi.

Early at the age of eight he learned Buddhism from eminent Xiao Yin (Da Su) of Jingci monastery at Lin'an. Then he learnt from eminent monks Guang Zhi and Hui Ji. At 14 he took monastic vows and at 20 he received all the authority of a monk.

In the 4th year of the Hongwu's reign, the Emperor summoned Zong Le to the capital and appointed him abbot of the Da-tian-jie-si monastery and concurrently director of the Shan Shi Council to fulfill the vacant post left by Hui Tan's death.

It was not an accidental phenomenon that the Emperor made this appointment.

It was because the monks of the Da-tian-jie-si monastery had a special relationship with Tibetan monks.

All the Yuan emperors believed in Tibetan Buddhism. The first abbot of the Da-long-xiang-si monastery was Guang Zhi, who was most probably a Tibetan monk.

According to the Jin-ling-fan-cha-zhi (An Account of Buddhist Monasteries at Jinling), Guang Zhi was an Indian monk. In fact the so-called Indian monks in Chinese documents of the Yuan and Ming dynasties were not natives of India. Instead, most of them were Tibetans and a small number came from Kashmir.

In the late 10th century Arabians invaded India. Since then the Arabian rulers converted Indian people to Islam by force. India was soon Islamized. Buddhism in India declined and almost came to an end in the 13th century.

It was not until the second half of the 19th century Buddhism somewhat recovered in India.

The "Biography of Monk Sakya Yeshe of the Xiantong Monastery at the Wutaishan Mountain in Ming Dynastery" in the Xing-xu-gao-seng-zhuan (A New Sequel to Biographies of Eminent Monks) vol. 19 said: "Sakya Yeshe was a native of Kapilavastu in India, the same place as Shakyamuni… He came to the Xiantong monastery in the 12th year of the Yongle reign of the Ming Dynasty. In the 11th month the Ming Emperor sent eunuch Hou Xian to invite Sakya Yeshe to the palace at the capital city.

The Emperor exempted him from bowing down and let him be seated at the Dashan hall. The Emperor had an interview with him, and appointed him abbot of the Nengren monastery… The next year the Emperor granted him a gold seal and the title of ‘Son of Buddha at the Pure-land, Great state Preceptor of Good Enlightenment, Perfect Comprehension,Wisdom, Mercy, Supporting the Country. Preaching the Religion, Initiation, and Propagating Virtue'."

Anybody who has learned even a little of Tibetan history knows that the Sakya Yeshe was a disciple of Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelug Sect of Tibetan Buddhism. In the Xuande reign of the Ming Dynasty he was granted another honorific title of "Dharma Lord of Great Mercy."

So it is clear that Sakya Yeshe was not an Indian monk.

According to the Xin-xu-gao-seng-zhuan (A New Sequel to Biographies of Eminent Monks), Hui Tan was a disciple of Sakya Yeshe. Naturally they both were appointed abbot of Da-long-xiang-si monastery one after another.

Hui Tan fell ill in the 3rd year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty, but he still went on as an envoy to the West Regions.

This showed that some of his abilities were applicable to the conditions required by the mission such as his knowledge of a certmn language and folk customs of the West Regions, which other Chinese monks did not have.

After Hui Tan died, Zong Le was an appropriate candidate for the post of abbot.

The reason was that he and Hui Tan shared the same tutor, Guang Zhi, and according to history books, he learned Sanskrit at a young age. It was quite possible that the records mistook the Tibetan as Sanskrit.

He went to Ngari under the excuse of "searching for Buddhist sutras." Then he translated the sutras he had collected. He was included in the "Chapter of sutra-translators" in a history book. This record was a proof of his language ability.

Zong Le presided over the Tianjie monastery for six years from the 4th year of the Hongwu reign when he was appointed abbot of the Tianjie Monastery to the 10th year of that reign when he went as an envoy of the Emperor to Tibetan areas.

In the six years he was in charge of the monastery's daily affairs, he gave religious sermons, made annotations on the Heart Sutra, Diamond Sutra and the Lankavatara Sutra by the Emperor's order, and composed Buddhist music. The Ming Emperor Taizu treated him well.

"The Emperor often went to see him, gave him good food, wrote poems in reply to his, and called him ‘Reverend Le'."

According to Ming Shi (History of Ming Dynasty), there were only two volumes of annotations made by Zong Le, one on the Heart Sutra and the other on Diamond Sutra. 19

We do not know whether the annotations he made on Lankavatara Sutra were finished or lost. As to the music he composed to praise the Buddha, it can be proven by a poem about him offering the music to the Emperor.

The poem entitled "Jinying-zhi-xian-fo-yue-zhang" (Offering the Composed Buddhist Music to the Emperor) was collected in the book entitled Quan Shi Wai Ji. 20

According to "Records of Officials" of Ming Shi (History of Ming Dynasty), the Shan Shi Council was cancelled in the 4th year of the Hongwu reign. So Zong Le was not in the high post of vice 2nd-ranking official However, Ming Emperor Taizu bestowed on him special favours.

When the Shan Shi Council was set up, many court ministers were opposed to it. Their opposition did not succeed because Zong Le was then in charge of the Council. When Zong Le left for the West Regions, the council was cancelled.

Though the agency was set up again afterwards under the Central Buddhist Registry, its director's official rank was only the 6th. That is, his official position was much reduced. However, this did not make tile Ming Emperor Taizu, or Zhu Yuanzhang underestimate the influence of eminent monks.

The Emperor always thought that Buddhism could play a great role, so he persistently sought out eminent monks The Emperor was in close relationship with Zong Le from the 4th to the 10th year of the Hongwu period.

The Emperor often at year of the Hongwu period. The Emperor often at-tended Zong Le's sermons, ordered the royal kitchen to serve him with food every day, often invited him to the royal palace, wrote poems in response to his and affectionately called him "Reverend Le." Zong Le was grateful to the Emperor.

In order to repay the Emperor's favours he was willing to go to the West Regions as an envov. Though he was a Buddhist monk, Confucianism still influenced Zoug Le. Confucianism advocated that one should faithfully serve his emperor and surrender his service to those who appreciated his ability.

It was in the 14th year of Hongwu period that Zong Le returned from the West Regions to report his mission to the Emperor.

Historical books did not record when he went to the West Regions. According to Bu Xu Gao Seng Zhuan, it was in the winter of the 10th year of Hongwu period.

Xu Yi said in his preface to Quan Shi Wai Ji, "Zong Le was ordered by the Emperor to go to the West Regions for the Buddha's sutras Going to and fro from the West Regions he traveled for several ten thousand li through desert land and wildness.

The journey took him five years and made him suffer much from many hardships." The "five years" indicated that Zong Le left in the 10th year of ttongwu period.

All the relevant documents say that he went there for Buddhist sutras. From the then conditions it can be seen that his actual purpose was to declare the Emperor's pacifying policy to the upper classes of monks and laymen of Ngari.

As mentioned above, the Ming Emperor Thizu established a Commander in charge of military and civil affairs of Ngari in the 8th year of the Hongwu period to follow the convention of Yuan dynasty.

However, the monks and laymen of Ngari did not come to show allegiance to the Ming Dynasty. Perhaps they did not know of the replacement of the Yuan by the Ming. In any case the Ming court had to send an envoy to declare its policy. Zong Le was the most appropriate candidate.

If the journey were for Buddhist sutras only, then the Emperor's order would nOt have been a necessity.

It was recorded that Zong Le wrote A Travel to the West, in one volume, after he returned from the West Regions. 21 "The book was about his travel as an envoy to the west." "It should have rich contents" 22 Unfortunately, the important travel notes have been lost Even the editors of Si Ku Quan Shu (the Four Treasures of Books) didn't find it. It is impossible for us to find it now.

The records in the "Ji-mao" entry of the 12th month of the 14th year of the Hongwu period said: "In the wu-chen day of the 12th month of the 11th year (1378) of Hongwu period, Monk Zong Le and his party were dispatched as envoys to the West Regions" 23 "Zong Le returned from the West Regions.

The envoys of the Commander in charge of the military and civil affairs of Ngari, and of Ba-zhe myriarchy (administrative district), came together with him to offer tributes to the court." 24

The "West Regions" here denotes Tibetan areas. In the Ming Shi, the historical events of Tibetan areas were recorded in the section of Xi Yu Zhuan (Records of West Regions).

Chinese words "E-li-si" were the transliteration of Tibetan word mngavris (Ngari).

The Ngari in the Ming Dynasty included what is now Tibet's Ngari district and a large stretch of land to its southwest.

In about the 6th century it was called Greater and Lesser Shangshung (Yangtong). In the early 7th century Songtsen Gampo of Tubo captured it. It became a subordinate to Tubo.

Owing to the uprising of serfs, Kyide Nyimagon (skyi-ide-nyi-ma-mgon), a descendant of Tubo royal family, fled to Tsabrang of Shangshung (now Zada of Tibet) at the end of the 9th century.

Then his three sons founded Lhadak (now Kashmir), Purang (now Tibet's Burang) and Guge (With Zada as its center) respectively. Since then the Greater and Lesser Yangtong (Shangshung) were renamed "Ngari Korsum" (mngav-ris-skor-gsummeaning ‘the three parts of Ngari').

The Yuan government established the Pacification Commission and Chief Military Command of the Three Circuits of U-Tsang and Ngari Korsum, whose jurisdiction was over an area that is similar to what is now the Tibet Autononlous Region.

It was under the control of five Pacification Commissioners and two chief military commanders of Ngari Korsum.

This showed that Ngari was an area under militarv control. 25

The Chinese words "E-li-si" in Ming Shi Lu were a transliteration of "Ngari" As to "Ba-zhe" myriarchy we do not know its Tibetan expression, nor its locality. There was not a Ba-zhe myriarchy among the thirteen myriarchies granted by the Yuan Dynasty.

Since the envoy of Ba-zhe came to the capital together with that of E-li-si (Ngari), the Ba-zhe myriarchy should be in Ngari Among the thirteen myriarchies recorded in "Bai Guan Zhi"

(Records of Officials) of Yuan Shi (History of the Yuan Dynasty) was a myriarchy called "mngav-ris-rdzong-khavi-vog-gi-blo-da-lo-rdzong"The Ba-zhe myriarchy, I think. was nominally under the administration of U-Tsang but was located in Ngari.

It was the only myriarchy with the word "Ngari" in its title, so it should be related with Ngari. Therefore, the "mngav-ris-rdzong-khavi-vog-gi-blo-da-lo-rdzong" myriarchy in the Ming Shi Lu was perhaps the Ba-zhe myriarchy, but this remains to be proved.

The Ngari Military Command was established in the 8th year of Hongwu's reign of the Ming Dynasty. 26 Generally, a local administration should be set up after the local government offering tribute in response to the central government's call for pacification.

In the light of the historical records of the Ming Dynasty, the Ngari local government for the first time sent envoys to pay tribute to the central government in the 14th year of the Hongwu's reign because the journey was difficult and long. Following the Yuan's practice, the Ming established a Military Command in Ngari.

This was before Ming's pacification of Ngari local regime In the 6th year of Hongwu period, the acting Imperial Preceptor NamgyeI Palzangpo recommended to the Ming court 60 Tibetan local officials who had been appointed by the former Yuan court Some Ming ministers opposed to the recommendation, claiming,

"only those who have come to the imperial court to offer their allegiance could be reappointed, but those who have not come should not be reappointed.

But the Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang insisted that all the Tibetan local officials appointed by the Yuan Dynasty, no matter whether they had come to the imperial court personally to offer their allegiance or not, should be accepted and reappointed. 27

3. Zhi Guang as an envoy to Tibetan areas.

Regarding monk Zhi Guang's life story we can con-suit Mr. Deng Ruiling's article entitled "Ming Xi-tian Fo-zi Da-guo-shi Zhi Guang Shi-ji Kao" (A Textual Research into Life Story of Zhi Guang, Son of Buddha and Great State Preceptor). 28

This research was based on full and accurate data about Zhi Guang, except the "Biography of Zhi Guang" in Xin Xu Gao Sheng Zhuan.

According to Xi-tian Fo-zi Da-guo-shi Ta-Ming Xu (Preface to the Inscriptions on Memorial Pagoda of Son of Buddha of the Pure-land, the Great State Preceptor) 29, and "Ming Jin-ling Zhong-shan Xi-tian-si Sha-men Shi Zhi-Guang Zhuan" (Biography of Zhi Guang, Monk of Xi-tian-si Monastery at Mt Zhongshan of Jinling in Ming Dynasty) of Xin Xu Gao Seng Zhuan, vol. 2,

Zhi Guang was surnamed Wang and was a native of Qingyun of Wudingzhou Prefecture of Shandong (now the Qingyun Count), of Shandong Province).

He was born in the 12th month of the 8th year of the Zhizheng reign of the Yuan Dynasty. At the age of 15 he was ordained as a monk in the Ji-xiang Fa-run-si monastery at the capital city Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty, His religious tutor was Sahazashri,

a Pandita (a title of honor to Buddhist monk who was good at the Five Major Sciences of ancient India) of Kashimira (now Kashmir), who had a good command of the Five Major Sciences of ancient India and knew Sanskrit very well.

He came to propagate Buddhism in China by the end of the Yuan Dynasty. He was a famous traveler and a great propagator of Buddhism He had influence on Zhi Guang's whole life.

When the Ming Dynasty was founded, Zhi Guang with his disciples had an audience with the Ming Emperor Taizu.

The Emperor found that Zhi Guang was proficient at the Sanskrit (actually, Tibetan) and the Chinese language, and thus ordered him to stay in the Zhongshan monastery and translate the Buddhist scriptures his tutor had collected.

In his translation work Zhi Guang was good at using simple words to express accurately the deep meaning. The Emperor appreciated that very much.

Then the Emperor dispatched Zhi Guang as an envoy with his disciple Hui Bian to the West Regions.

Zhi Guang was dispatched to the regions three times altogether. Two times were in the Hongwu reign and one in the Yongle reign.

In the 10th year of the Xuande reign he was granted the honorific titles of "Son of Buddha of the Pure-land" and "Great State Preceptor."

In the 6th month of the same year he died and a grand funeral ceremony was held for him in San-ta-si (monastery with three pagodas) monastery outside the Fuchengmen gate of Beijing.

Zhi Guang went as an envoy to Tibetan areas twice; one of them was in the 17th year of the Hongwu reign "The Inscription on the Tomb Pagoda" said:

Zhi Guang with his disciple Hui Bian went as Emperor's envoy to the Western Regions in the Jiazi year (the 17th year) of Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty (1384)

He arrived in Nepala, a kingdom of Hindus where he propagated the Ming emperor's pacifying policies to the regions This propagation was welcomed by the local people.

He met with Buddhist master Mahe Bodhi, who held forty-two prayer meetings of Thunderbolt Mandala The king held him in high esteem." It was recorded in the Ming Shi Lu's Ji Wei entry of the 2nd month of the 17th year of the Hongwu reign that "Zhi Guang with his party went as the Emperor's envoy to Nepala, a kingdom of Hindus"

This record and that of the "Inscription of Pagoda" had the same content. They can prove each other.

The Nepala was in today's Kathmandu valley of Nepal. Nepala was the farthest destination of Zhi Guang's westward iourney.

Mr. Deng Ruiling said: "After the 13th century Buddhist sacred sites around Bihar in the Central Hindu were destroyed by the Islamites and so Buddhist scholars fled to Nepala.

As a result, the Tibetans used to go to Nepala for learning Buddhism. Zhi Guang must have gone southward along the road from Tibet to Nepala.

He traveled in the eastern and western parts of the valley and learned Tantrism from a Mahayana Buddhist monk who knew Buddhist sutras very well."30 I agree entirely with Deng's inference and here I would like to add a little more.

I think, the rulers of the dynasties in the hin?terland at that time had only an obscure idea of borderland. In the Han and Tang dynasties the West?ern Regions (a general geographical term) were under the control of the imperial dynasty of the hinterland.

The rulers of the Ming dynasty following the example of previous dynasties also dispatched envoys to the regions and the envoys went as far as they could.

This was done more prominently in the Yongle reign of the Ming Dynasty.

Zhi Guang returned from the Western Regions in the 20th year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty. Together with him were envoys of Nepala, U-Tsang and Do-kham.

According to Ming Shi Lu, "In the 12th month of the 20th year of the Hongwu reign, Madanalamo, king of the kingdom of Nepala, as well as Sogru Gyaltsen and other chiefs of U-Tsang and Do-Kham,

commanders in charge of the Tibetan Amdo area, dispatched their envoys to the capital to offer such tributes as horses, swords, golden mini-pa?godas and Buddhist sutras for celebrating the next New Year's Day.

" "Monk Zhi Guang and his party returned from Nepala. He offered eight horses as tribute but his tribute was declined."31

Ming Shi (History of the Ming Dynasty) has no record of his second mission.

The"Inscription on the Pagoda"said: "He came back and went there again.

Then he led a group of the local people to the capital. "Other tablets had the same record His second return should have been in the lath month of the 23rd year of the Hongwu reign (1390).

Ming Shi Lu said:

"On the geng-chen day of the 12th month of the 23rd year of the Hongwu reign, the aboriginal officials from the Western Regions came to the capital to pay tributes to the imperial court and to offer their good wishes for the coming New Year.

They were envoys sent by the Nepala kingdom, by the State Preceptor of Initiation Drakpa Gyaltsen Palzangpo, by the Yamdrok Regional Military Commission of U-Tsang,

by Gongkar Pashi, the ex-Situ of Amdo, by Paljor Zangpo, Commander of Regional Military Commission of U-Tsang,

by Kongpo Gyaltsen, the Director of the Branch of Regional Military Commission of U-Tsang, by Lespe Namgyel, by Karpa Nyangpo, by Dondrup Zangpo of Drathang Qianhu (chief of 1000 households),

by the Pacification Commissioner named Legpa Dondrup, by the chief of U-Tsang Commanery named Dorje Zangpo, by Panjor Zangpo, and by Shonnu Zangpo, as well as Zasakpa sent by monk Sengtak of the Dewatsan Nlonastery." 32

Drakpa Gyaltsen Palzangpo ([[grags-pa-rgyal-mtshan-dpal-bzang-po]), now abbreviated to Drakpa Gyaltsen, was a leader of Phagmo Drupa politico-religious regime, the most influential local group of U-Tsang in the Ming Dynasty.

Phagmo Drupa was one of the thirteen myriarchies in the Yuan Dynasty.

In the Ming Dynasty the Phagmo Drupa regime was so arrogant in its great power that other local political and religious groups had to follow its lead. Its attitude to the central government exerted direct influence on the political stability of U-Tsang.

The so-called "Yamdrok" (yar-vbrog) and "Tshalpa" cited in the Ming Shi Lu also were influential political regimes of Tibet. It was quite possible that the envoys sent by Tibetan politico-religious leaders to pay tribute came to the capital together with Zhi Guang.

IV. Some Reflections on the propagation of Tibetan Buddhism in the hinterland during the Ming Dynasty

1. Ming's policy of pacification by granting various new offices and titles of honour to local leaders in the Tibetan areas was in accordance with China's actual situation at that time.

It should be said the Ming's policy toward Tibet was a very sensible one. The making of this policy was some what related with the Ming Emperor Zhu

caused trouble in the society and made a severe drain on the state treasury in interior China However, this policy had good results. Within decades the administration of Tibetan areas was improved in the early Ming Dynasty.

In a period of about three hundred years the Ming imperial court did not dispatch troops to Tibetan areas and the Tibetans did not worry about either war or loss of territory.

So, all Tibetan tribes paid tributes to offer allegiance to the central government.

This was because the Ming's policy toward Tibetan areas was in accordance with actual conditions in the hinterland and Tibetan areas at that time.

2. The important role of eminent monks of Tibetan Buddhism

In the Ming Dynasty, many eminent monks of Tibetan Buddhism were granted honorific titles.

The road between Tibet and the capital city saw numerous Tibetan monks going to pay tribute to the central government.

Some Tibetan monks were active in the Ming's socio-political arena.

They played an important role in maintaining the nation's unification and the unity of various ethnic groups of China for several hundred years. In this respect nobody could replace the monks. Why could Tibetan monks play such an important role?

The people who know little about Tibetan culture raise this question.

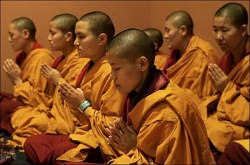

The important role of Tibetan monks reflected the key point of differences between Chinese Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism First of all, the Buddhism in Tibetan areas was an absolutely leading social ideology, which most Tibetan people believed in. Tibetan monks were respected and patronized.

On the other hand, in areas inhabited by the ethnic Han Chinese, where Confucianism was the leading ideology, the imperial examination system was the ideal way out for the people, and the most learned persons cried to become officials.

It was different in Tibetan areas where monks were the most learned among the people. So to be a monk was the best choice for the Tibetan people.

However, it was not easy to become an influential monk, who had to study Buddhism very hard for a long period of time and travel about a lot to propagate Buddhism.

In Tibetan history almost all learned people including historians, writers, poets, dramatists, painters and sculptors were monks, and most of the leaders of all circles of Tibetan society were monks. In the Ming Dynasty many influential leaders of political regimes in Tibetan areas were also leaders of religious sects.

They were the so-called politico-religious leaders of Tibetan local regimes.

Ruling monks made an unusual impact on the Tibetan people.

For example, at the turn of the Yuan and Ming, Sangyel Drashi, an eminent Tibetan monk of Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism was known for his excellent magic arts.

Thus he was called "Sea Immortal, Mahasiddhi (one who has attained spiritual accomplishments)" by Tibetan monks and lay people, and "Hai (sea) Lama" by local ethnic Han people.

He is called "Lama Sangyel, the Tibetan monk at Xining" in the Ming Shi and Ming Shi Lu. Lama Sangyel played an important role when the Ming court subdued the Tibetan tribes of Qinghai.

Ming Shi said: "In the 25th year of the Hongwu reign, Lan Yu, entitled as Duke of Liangguo, pursuing and attacking a fleeing bandit group sonal letter.

In the 30th year a Tibetan leader named Sonam Drakpa sent envoys to pay tribute to the Ming emperor, and the emperor appointed him the Military Inspector of Handong Command" 33

So, we can see that Lama Sangyel enjoyed very high prestige in Gansu and Qinghai.

With only a personal letter he could subdue the rebellion of troops of Handong Command and had them come over to the Ming dynasty. This event demonstrated to the Ming Emperor that important religious personages in the Tibetan areas had great influence over religious Tibetan people.

The Ming Emperor Taizu treated Tibetan monks very well.

Because historically all Tibetan people in Tibetan areas believed in religion, and the leaders of various religious sects were leaders of local political regimes.

The Tibetan eminent monks played an important role in Tibetan society. In this respect Chinese monks could not compare themselves with them. The Ming rulers knew it very well.

So they tried their best to draw over influential Tibetan monks and granted them various honorific titles and many gifts "Tibetan people devoted themselves to Buddhism, so we supported Tibetan Buddhism in order to draw over the people" 34

Most Ming emperors had good relations with Tibetan eminent monks and won their trust.

The Ming's pacification policy toward Tibet by granting ruling lamas new offices and honorific titles was carried out successfully.

When the religious 1eaders were pacified the common people in the areas under their control were also pacified.

3. The cultural exchange between the ethnic Tibetan and Han peoples being promoted.

Because of political reasons influential Tibetan monks often went to and fro between Tibetan areas and the hinterland in the Ming Dynasty. Tibetan Buddhism was an important carrier of Tibetan culture, so the monks had to be also propagators of Tibetan culture.

As an ethnic group with a long history of culture, the Han people are always tolerant toward foreign cultures. This was reflected by a Chinese saying, "the monks from afar are good at chanting sutras." The Ming imperial court and common people tolerantly accepted Tibetan Buddhism for a long period of time.

It was due to its own fascination that Tibetan Buddhism could spread to the hinterland.

Tibetan culture with Tibetan Buddhism as its core has rich contents Spreading eastward to the hinterland, it propagated not only religion but also culture. Culture is all embracing.

It covers language, writing, drawing, sculpture, architecture and so on.

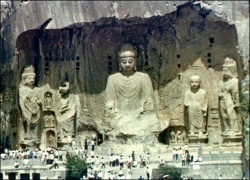

In order to meet the needs of Tibetan monks of taking residence, giving sermons and teaching disciples in the hinterland, the Ming imperial court built Tibetan monasteries in Nanjing and Beijing fur them, whose Tibetan style of architecture, wall paintings and sculpture much enriched the monastery culture in the hinterland.

What is more important is that Tantric Buddhism that had been lost for a long time in the hinterland now appeared and developed again.

Some Tantric sutras were translated into Chinese from Tibetan and some monks of Chinese Buddhism converted to Tibetan Tantrism.

Stories of Tibetan monks were recorded in personal notes, novels and official documents of the Ming Dynasty.

All these things made the people in the hinterland more and more understanding towards Tibetan culture. A part of the cream of the Tibetan culture was absorbed by the Chinese culture in the hinterland.

Cultural exchange is a matter of two sides. The Chinese culture is also very rich in content and covers a wide range. It exerted great influence on the eminent Tibetan monks who went to and fro between Tibet and the hinterland.

The history of development of Tibetan culture saw two important periods of cultural development.

One was the Tubo period in which Tibetan culture was greatly influenced by the Chinese culture in the Tang Dynasty.

The other was the period from the 15th to 17th century, in which Tibetan culture was influenced by the Chinese culture in the Ming Dynasty. Besides, the Ming rulers' great sup port promoted the development of Tibetan culture.

For example, in the 8th year of the Yongle reign of the Ming Dynasty (1410), the Ming Emperor Yongle or called Chengzu appointed Deshin Shekpa, the Great Treasure Prince of Dharma, as the chief editor of the Nanjing-version Kangyur of Tripitaka based on the Kangyur compiled by Tsalpa. The Yongle edition of the Kangyur was the earliest one.

Its plates were copper instead of wood.

The Wanli edition of the Kangyur was printed in Beijing in the 33rd year of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasw (1605). These two editions played a very important role in preserving and spreading Tibetan Tripitaka.

Notes:

1. "Shi Lao Zbuan" (Biographies of Monks and Taoists) in the Yuan Shi (History ofthe Yuan Dynasty), vol. 202

2. See the Ding-si item of the 12th month of the 18th year of the Hongwu reign in the Ming Shi Lu (Documentary Records of the Ming History), vol. 176 3. Yu Minzhong (of the Qing Dynasty), Ri Xia Jiu Wen Kao (Notes of Old Events Happened in the Capital City), p. 844, Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House, P. 844

4. Pawo Tsula Trengwa (1504-1566), A Happy Feast for Wise Men (Tibetan edition) (1564), Beijing Minzu Publishing House, 1986, PP. 1001-1002, Tibetan stereotype 5. See Liu Ruoyu (of the Ming Dynasty), Zbuo Zhong Zhi

6. Deng Zhi cheng, Gu Dong Suo Fi, published by China Book store in July 1991, p. 593

7. Feng Chengjun, Ting Ya Sheng Lan fiao Zhu Xu, published by China Book Company in 1955

8. Li shihou "Zheng He's Great Contributions and His Family Lineage," in A Collection of Artides on Zbeng He's Trips to the Western Ocean, vol. i, p. 360 9. "The Western Regions," part 3, in Ming Shi (History of the Ming Dynasty) vol. 331

10. Liu Ruoyu, Zhuo Zhong Zhi

11. Ming Shi Lu (Documentary Records of the Ming History) vol. 53, Liang edition. 12. 13. "Biography of Hui Tan, a Monk of Da-tian-jie-si Monastery at Jinling in Ming Dynasty" in Xing Xu Gao Seng Zhuan (A New Sequel to the Biographies of Eminent Monks) vol. 34

14. The geng-zi item of the first month of the first year of Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty in Ming Tai Zu Shi Lu (Documentary Records of Ming Emperor Taizu) vol. 29. Also see Guo gue, vol. 3.

15. "The Tablet in the Ming-Jue Monastery" in Song Xue Shi Wen Fi (A Collection of Essays of Scholars of the Song Dynasty) 16. Xin Xu Gao Seng Zbuan (A New Sequel to the Biographies of Eminent Monks) vol. 34. The He-la Kingdom was in the area of Yanqi of Xinjiang. There was He-la-chi tribe at Yanqi in the period of the Kin Dynasty.

17. Published in China Tibetology, vol. 1, 1992 18. The kui-bai item of the 6th month of the 3rd year of the Hongawu reign of the Ming Dynasty in the Ming Shi Lu, vol. 53.

19. "Yi Wen Zhi" (Records on Arts and Literature), vol. 3, in Ming Shi, vol. 98.

20 Zong Le, guan Shi Wai Fi, vol. 6 21 "Yi Wen Zhi" (Records on Arts and Literature), vol. 4, in Ming shi (History of the Ming Dynasty) vol. 99 22 Si Ku Zong Mu Ti Yao (An Outline of the General Contents of the Four Treasuries of Books), vol. 170. Also see "Bie Ji Lei", vol 23, in A Sequel to guan Shi Wai Fi. 23 Ming Tai Zu Shi Lu (Documentaly Records of the Ming Emperor Taizu). vol. 121.

24 Ming Tai Zu Shi Lu vol. 140 25 Chcn De zhi "On the Year When the U-Tsang Pacification Commission of the Yuan Dynasty was Established" in A Study of the Hirtory of the Yuan Dynasty and the History of the Northern Ethnic Groups, vol. 8, 1984 26. 27. "The Western Regions," vol. 3, in Ming Shi (History of the Ming Dynasty), vol. 331 28. Published in China Tibetology, vol. 3, 1994 29 Edited by Yang Rong (in Ming Dynasty). The Pagoda was built half a year after Zhi Guang's death. The preface was the first-hand material for the study of Zhi Guang's life.

The Inscription on the Memorial Pagoda for Zhi Guang was not collected in Yang Rong's Yang Wen Ming Gong Fi (A Collection of the Essays by Yang Wenmin). A copy of the inscription is preserved in the Rare Book Department of the Beijing National Library. 30. Deng Ruiling, "A Textual Research into Lire Story of Zhi Guang, Son of Buddha and Great State Preceptor" published in China Tibetolog. vol. 3, 1994 31 Ming Tai Zu Shi Lu vol. 187, Guan edition 32 Ming Tai Zu Shi Lu vol. 206, Guan edition 33 "The Western Regions," part 2, in Ming Shi, vol. 330 34 The item of the 2nd month of the 30th) year of the Hongwu reign in Ming Shi Lu, vol. 250

Prom China Tibetology (Chinese Edition) No. 4, 1998 Translated by Chen Guansheng and Li Peizhu