Meru Nyingpa

Meru Nyingpa Monastery (rme ru rnying pa)

by Will Rourk

Introduction

Meru Nyingpa Monastery is located in the Barkor area at the heart of the old city of Lhasa, just east of the famed Jokhang Temple. Meru Nyingpa is an unassuming monastery nestled deep within the labyrinthine alleyways and whitewashed walls of the old Barkor neighborhood (view Meru Nyingpa’s location in the Barkor).

Meru Nyingpa has a long history that reaches back to the founding of the Jokhang, and indeed to the origins of Buddhism in Tibet itself, in the seventh century. The Jokhang, housed within the larger complex of the Tsuklakkhang, is an iconic structure and the central chapel of the Tibetan Buddhist world.

Meru Nyingpa has many qualities that make it a unique monastic complex located within the center of Lhasa, the holiest of Tibetan Buddhist cities. The structure of Meru Nyingpa contains the elements that describe the quintessential Tibetan Buddhist monastery. Sections of the essay that follows examine the history, layout, construction, and architecture of Meru Nyingpa to reveal the composition of a Tibetan Buddhist monastery.

The History of Meru Nyingpa Monastery

Songtsen Gampo and the Founding of Meru Nyingpa

The site upon which Meru Nyingpa was built has its earliest associations with the thirty-third Tibetan king, Songtsen Gampo (ca. 617-650 CE), whom Tibetans credit with the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet. To establish diplomatic ties with Tibet’s neighbors, Songtsen Gampo married Princess Bhṛkuṭi (Tritsün) of Nepal and Princess Wencheng of China.

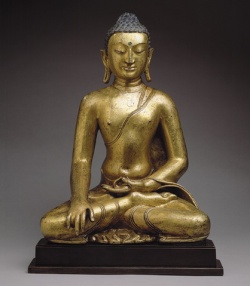

Wencheng brought a Jo bo Śākyamuni statue with her as part of her dowry; this statue is housed in the Jokhang (built ca. 647 CE) Temple and is revered as Tibet’s most sacred object.1 The Jokhang Temple has since its founding been the central focus of pilgrimage for all Tibetan Buddhists and its location marks the center of old Lhasa. It is on the eastern boundary of this temple complex that Meru Nyingpa Monastery evolved.

Meru Nyingpa Etymology

To anyone familiar with Buddhist iconography, “meru” in the name Meru Nyingpa might seem to allude to the mythical Mount Meru, the axis mundi of Indian Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain cosmology. Tibetan Buddhists believe that Mount Kailash in Western Tibet is the physical embodiment of Mount Meru. However, “meru” here is a Sanskrit word, so an etymological explanation of Meru Nyingpa in terms of Tibetan language is required.

The Tibetan etymology of Meru Nyingpa is not at all clear. A historical interpretation proposes that meru is a name given by the forty-first Tibetan king, Khri Ral pa can (ca. 806-840), in the ninth century. This theory holds that Meru Nyingpa was originally known as “Red Horn” (marru), though nowhere is there any documented history of a monastery with a reference to a horn in its name.2

Another explanation expounds further upon the color red in reference to the name of Meru. Khri Ral pa can is purported to have constructed two protector temples in each of the four directions of Lhasa, centered around the Jokhang Temple. Two temples were built in the east, one red and one white.3

The white chapel was known as “Karu,” an old Tibetan word for the color white, which in modern Tibetan is “karpo.” Similarly, the red temple was known as “marru” or “meru,” an old Tibetan word for “red,” which in modern Tibetan is “marpo.”4 This was a small temple built just east of the Jokhang and was referred to by [[Khri [Ral pa can]] as “Meru” or the “Red Chapel.”5

This temple is believed to be the Dzambhala Lhakhang, a chapel dedicated to the deity of wealth. This chapel still exists today and is the founding structure of the Meru Nyingpa complex.

In 1658 a new monastery, Meru Tratsang, was built to the northwest of Meru Nyingpa. When it was built, the monastery known as “Meru” became known as the “Old Meru Monastery” (Meru yingpa) to distinguish it from Meru Tratsang became known as “Meru Sarpa” or the “New Red Monastery.”6 The only clear relationship between the two monastic institutions is that Meru Sarpa is responsible for the operation of the Dzambhala Lhakhang within Meru Nyingpa.7

Meru Nyingpa during the “Dark Period” of Tibetan Buddhism

Buddhism struggled to gain acceptance in Tibet after its initial dissemination there, and at the same time the stability of the Tibetan empire began to erode. Around 840 CE Khri Ral pa can was assassinated and was succeeded by his brother Langdarma, the forty-second and last king of Tibet.8

With his assassination in 842, the Tibetan empire dissolved and Tibetan culture was plunged into a period of great strife and chaos. The early incarnation of Meru Nyingpa apparently was severely damaged during this period.9

The Second Diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet

The second diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet began during the late tenth century when monks who had fled to the eastern Tibetan province of Amdo returned to Lhasa to restore Buddhism to Tibet. One of the greatest influences in the revival of Tibetan Buddhism was an Indian monk known as Atiśa.

Atiśa arrived in Tibet in 1042 at the invitation of Buddhist kings who ruled in Western Tibet.10 During this time Meru Nyingpa was rebuilt, and its monastic community was able to re-establish itself.11 This community has remained intact over the centuries with the exception of a brief period during the twentieth century.

The Rise of the Dalai Lamas

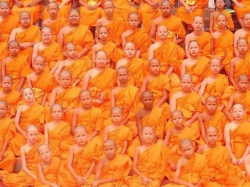

Over the next few centuries major religious schools of Tibetan Buddhism would be established that would influence the building of large monasteries to accommodate the increasing population of monks. From the Gelukpa School, founded by Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), emerged the institution of the Dalai Lamas. In the mid- to late-sixteenth century, Meru Nyingpa was converted to a Gelukpa monastery during the lifetime of the Third Dalai Lama.

During the seventeenth century the “Great Fifth” Dalai Lama was installed as the political leader of Tibet after a civil war in central Tibet in which the Mongols played a decisive role.

The Fifth Dalai Lama greatly expanded the monastic grounds of Meru Nyingpa by adding a central three-story temple with surrounding monks’ quarters and stables forming a large courtyard space within.12 This was done in preparation for providing a permanent residence for the Nechung Oracle.

The Nechung Oracle

The role of the Nechung Oracle was to serve as a vehicle through whom the Buddhist deities would speak to the Tibetan government. The Oracle primarily served the Dalai Lamas and through him the protector deities of Buddhism would ensure the security of Tibet.

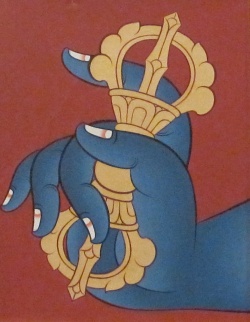

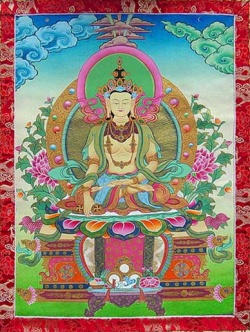

The principal protector deity of the Tibetan government, Dorjé Drakden, was made manifest through the Oracle who would summon the deity in a trance state (figure 2). Through him the questions concerning the future well being of Tibet would be answered.13 To provide a residence to such a prestigious member of Tibetan government and religion was a great honor to the newly expanded monastery of Meru Nyingpa.

Dorjé Drakden became the main protector deity of Meru Nyingpa and his images can be found in the main temple as well as the Dzambhala Lhakhang where the Oracle originally took up residence. During the festival of Mönlam, the Great Prayer Festival, the monks from the Nechung monastery, located northwest of Lhasa adjacent to the great monastery of Drepung, would congregate at this location.14 Later the residence of the Nechung Oracle would be located in the central chapel (lhakhang) of the main temple.

The Three Meru Nyingpa Chapels

Three main chapels were established at Meru Nyingpa from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The Dzambhala Lhakhang was managed by the monastic college to the north of Meru Nyingpa, Meru Tratsang, after its establishment in 1658. Perhaps at this time the monastic complex of Meru Nyingpa was referred to as the “Old Red Monastery” since Meru Tratsang became commonly known as Meru Sarpa or the “New Red Monastery.”15

On the level just above the Dzambhala Lhakhang, the Pelgön Khang was established by the Gongkar Chödé monks from Lhokha prefecture in Southern Tibet.16 This small chapel had as its principal image Gönpo Pelgön Dramsé, a manifestation of Mahakala, one of the chief protector deities of Tibetan Buddhism.17

The main central temple and assembly hall were chiefly established during the reign of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama (1895-1933). This was achieved by the Nechung abbot, Sakya Ngape, in order that the Nechung Oracle be given a permanent residence. The Oracle would stay here whenever he came to Lhasa18

As a result of the various monastic factions taking up residence at Meru Nyingpa, the monastery was under the unique condition of being administered by three different schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Sakyapa were represented by the monks of Gongkar Chödé residing in the Pelgön Khang and the Dzambhala Lhakhang retained its Gelukpa affiliation with Meru Tratsang.

The main chapel which was administered by the Nechung monks represented the Nyingmapa or “ancient” sect of Tibetan Buddhism chiefly because of the association with the older protector deity of Pehar who communicated through Dorjé Drakden to the Nechung Oracle.19 These chapels are still active today and continue to represent these three schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

Early Twentieth-Century Expansion

During the early twentieth century the monastery of Meru Nyingpa underwent another dramatic change. During the reign of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the Nechung abbot, Sakya Ngape, rebuilt the central building along the north side of the complex and the result is the temple that is currently present on the site.20 Until this time the configuration of Meru Nyingpa was such that the main entrance to the complex was accessed from the outer southern wing.

The early twentieth-century restructuring placed the main entrance in the northwest corner which is where the complex is currently entered.

This renovation was carried out by the Nechung abbot to transform Meru Nyingpa’s central temple into a branch chapel of Nechung Monastery.

The Meru Nyingpa main temple was consecrated to the Guardians of Buddhist Law (chökyong) of which Dorjé Drakden is associated.21 The residence of the Nechung Oracle was located within this central temple at this time.

To this day a group of Nechung monks will rotate about every six months at Meru Nyingpa to perform the duties of maintaining the main temple and carrying out its rituals.

The People’s Republic of China

In 1949 the People’s Republic of China was established under Mao Zedong and shortly thereafter its army occupied Tibet. During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s Meru Nyingpa was shut down and its monks were moved out.

The monks’ quarters were converted to lay residences and stables. Many images and statues were removed and much of the wall murals that decorated the interior of the main chapel were painted over. However, Meru Nyingpa escaped the fate of many other Tibetan monasteries that were either destroyed or irreparably damaged. It was mostly left intact and in 1980 it was re-opened to the monks.

By 1985 the monks had restored what they could of the main building and opened part of the complex for religious services.22 Meru Nyingpa would exist from this point on as a compound that accommodated both secular residences and religious facilities.

This status of the Meru Nyingpa compound would also reflect the transition that took place all over the Barkor neighborhood as an increasing number of religious and aristocratic buildings would be reinstated as secular residences.

The Tibet Heritage Fund

In the early 1990s Lhasa underwent a major urban re-development phase which saw further destruction of traditional architecture, drastically transforming the urban fabric.

By the late 1990s Meru Nyingpa was in danger of dilapidation from misuse and poor maintenance due in part to the devastation of the Cultural Revolution.

In 1996 the Tibet Heritage Fund, a German non-profit organization committed to historic preservation of traditional Tibetan architecture and preservation of Tibetan cultural heritage, began a massive restoration project in Lhasa’s traditional core, the Barkor neighborhood.

Their conservation projects re-awakened traditional building techniques and materials by employing traditional Tibetan craftsmen whose education pre-dated the Cultural Revolution. The THF hired these specialists to supervise the reconstruction of traditional buildings.

In many of their projects the secular tenants were allowed to retain their residences while also contributing to the effort of improving their buildings. Not only did the THF provide reconstruction assistance, but they also made measured drawings, created conservation maps, launched websites devoted to informing the public about Tibetan architecture, and developed an online database of Lhasa’s historic buildings.

The THF created conservation zones centered around the Barkor neighborhood that kept several buildings secure from demolition. With the creation of a secure conservation zone the THF was able to focus on seventy-six religious and secular buildings of great historic significance to Tibetan traditional architecture. Meru Nyingpa was one of those buildings that became a THF conservation project.23

The original focusdential buildings such as the many aristocratic “mansions” that balanced the religious composition of Lhasa’s traditional core. Due to the mounting number of requests from the monastic community, the THF began to consider the renovation of Meru Nyingpa even though it was already a functional monastic facility. Due to years of neglect Meru Nyingpa’s structure was in decay and badly in need of repair.

Also important was Meru Nyingpa’s location within the heart of Lhasa’s most historic conservation district in the Barkor neighborhood. In 1998, after receiving permissions from the Religious Affairs Department and other Chinese governmental offices, the THF received funding from the Federal German Embassy in Beijing to begin conservation work on Meru Nyingpa. 24

Much of Meru Nyingpa’s structural system was corrected through the replacement of wooden pillars and beams. Toilet facilities were upgraded, including the installation of a new facility in the main temple with a solar shower to accommodate the monks.

Electric lines were connected to the buildings to bring electricity to many of the rooms. Many of Meru Nyingpa’s secular residents assisted the reconstruction work and as a result many of their residences were rehabilitated. The arka roof system was renewed as well as the frieze work found around the top of the main temple walls.

In addition to structural renovation much of the painted murals on the temple walls were restored. Tsewang Dorje, a well known traditional Tibetan painter, Dr. Uli Eltgen, a German restorer of painted works, and other traditional Tibetan painters were put to the task of uncovering the interior walls, which had been covered in green and blue paint, to reveal the magnificent Buddhist murals that lay beneath.

THF workers consulted with Meru Nyingpa monks to restore these murals to a proper state. New mani prayer wheels were put into place and old ones were restored. Meru Nyingpa’s open courtyard was converted from a dirt floor to a paved surface using hand cut stone blocks.

Within this space was placed a grand incense burner which is constantly being fed juniper by the many pilgrims and devoted Buddhist Tibetans that continually come to Meru Nyingpa to worship and partake in its ritual festivals. Though the Tibet Heritage Fund is no longer in Lhasa, many of the city’s residents express their gratitude for the great improvements made in their lives.25

[1] Victor Chan, Tibet Handbook (Chico, CA: Moon Publications, 1994), 63.

[2] André Alexander, personal communication, 5 October 2005.

[3] Red and white were colors of great significance in pre-Buddhist Tibetan culture. Red meat and white dairy products were the main staples that sustained the lives of early Tibetans.

Meat ceremonies (mardön) and dairy ceremonies (kardön) were common amongst nomadic cultures (Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Townscape, (London: Serindia, 2001), 51.). White also came to represent peacefulness, cleanliness, and good fortune. Red represented power, dignity, and honor in memory of past heroes and leaders (Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 51).

Red was also the color representing the king and his court, and was revealed through red clothing, red flags, and red palaces and buildings. In religious practices white offering cakes (torma) were offered to the Buddha while red offering cakes were offered to the protector deities (Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 51). The respect given to the colors of red and white seemed to have been represented in the two chapels built just east of the Jokhang.

Perhaps the White Chapel, or “Karu” as mentioned above, was built to honor the Buddha while “Marru,” or the Red Chapel, served as a protector chapel referred to as the Meru Chökhang by Khri Ral pa can in the ninth century (André Alexander, “A Clear Lamp Illuminating The Significance And Origin Of Historic Buildings And Monuments In Lhasa Barkor Street,” in The Old City of Lhasa, ed. John Harrison and Pimpim de Azevedo, [[[Wikipedia:Berlin|Berlin]]: Tibet Heritage Fund, 1999]).

[4] David Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, A Synoptic and Map-Based Introduction to the Rooms In the Meru Nyingpa Monastic Complex, (Charlottesville, VA: Tibetan and Himalayan Library, 2003).

[5] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[6] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[7] André Alexander, personal communication, 5 October 2005.

[8] Giuseppe Tucci, Tibet: Land of Snow, trans. J. E. Stapleton Driver, (London: P. Elek., 1973), 69.

[9] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[10] ppDavid L. Snellgrove[[ and Hugh Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, (Boston; London: Shambhala, 1995), 130.

[11] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 119.

[12] André Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang,” Tibet Heritage Fund, Retrieved 19 October 2005.

[13] “Nechung - The State Oracle of Tibet,” The Office of Tibet, Retrieved 16 November 2005.

[14] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[15] André Alexander, personal communication, 5 October 2005.

[16] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[17] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 119.

[18] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[19] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[20] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[21] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[22] Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang.”

[23] “Meru Nyingba Monastery,” Tibet Heritage Fund, Retrieved 10 October 2005.

[24] “Meru Nyingba Monastary.”

[25] Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang.”

Monastery Composition

General Monastic Layout

The general layout of a Tibetan monastic complex was first outlined in the vinaya, which describes a square central temple with courtyards appended to three sides. There would also exist a separate kitchen facility, a storehouse, meditation cells and bath house for the monks. There would be the accommodation for the act of circumambulation (korra). The circumambulation route is a circular path that involves movement around a sacred statue, shrine, or a holy building such as a central temple.26

The courtyard of the monastery (gönpa) would include a debating ground where monks put to the test their knowledge and understanding of Buddhist doctrine. Opening up to the courtyard would be the monks’ residence which may also include some monastic offices. Larger monasteries may have more than one temple, but there is always the presence of a large assembly hall (dukhang). There may also be a library which may exist as its own structure or may be accommodated within the main temple. Accompanying this facility could be a printing house where the Buddhist canons are printed on wood blocks.27

Meru Nyingpa Layout

As Meru Nyingpa evolved into its current form it adhered to a principally classical Tibetan monastic form. The whole complex is tightly enclosed within the surrounding structures of other Barkor buildings acting as a peripheral wall. Within this perimeter the Meru Nyingpa complex can be divided into 3 basic zones (figure 4).

The outer zone is composed of two-story residential quarters that comprise the east, south and west borders of the complex creating a “U” shaped set of buildings. The lower residences open directly to a stone courtyard while the upper story is a semi-enclosed gallery that runs the length of each wing. Rooms open to this gallery with access to the lower floors via stone stair cases and with access to the roof via timber stair “ladders.”

The northern end of the west wing contains the Dzambhala Lhakhang on the ground floor and the Pelgön Khang with incense burner on the first floor directly above. The Meru Nyingpa courtyard serves as the primary gathering place for pilgrims as well as the common area currently used by the lay residents. The courtyard zone also includes the extant western entrance corridor and a defunct entrance corridor to the east.

This open space serves as a buffer between the outer residential wings and the central inner zone of the main temple. The Meru Nyingpa temple comprises the center of the complex. The temple contains the central assembly hall or meeting hall of the monks and is entered via a grand southern entrance accessed from the courtyard.

The central part of the temple is primarily used for monastic purposes and for the enshrinement of Tibetan Buddhist icons. East and west wings flank each side of the central temple and include lay and monastic residences. The total layout is symmetrical upon the central north – south axis of the site.

[26] [Thubten Legshay Gyatsho]], Gateway to the Temple: Manual of Tibetan Monastic Customs, Art, Building, and Celebrations (Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1979), 39.

[27] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 40.

A Tour of Meru Nyingpa

Before Meru Nyingpa monastery was secularized it was a purely religious institution whose composition reflected the characteristic layout of a Tibetan Buddhist monastery. An illustration of the [[Meru] Nyingpa]] layout can illustrate the different functions that exist within a Tibetan monastery. The numbers given in parentheses reflect the numbers on the Meru Nyingpa floor plans (figures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

Entrance Portal and Main Entrance Corridor

(MN001, MN148)

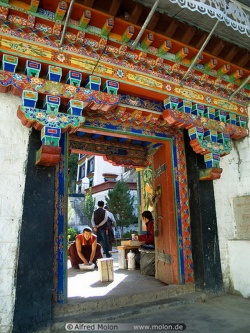

The Meru Nyingpa complex is entered from a northeast Barkor alley. Adjacent to the main entrance is the east entrance to the Jokhang or the Sera Dhaggo, which is used by Sera monastery’s monks and is opened only once a year during the Mönlam festival.28 Having entered the main western entrance on the north side, there is a corridor which is the main path for entering and departing from the Meru Nyingpa complex (figure 10).

An Exploration of the Residential Gallery Wings

Ṃani Wheels

(MN002)

Upon entering the corridor, on the right are three sets of mani prayer wheels that are turned by monks, visiting pilgrims and the lay practitioners of Buddhism. A mani wheel is a cylinder upon which spins the mantra oṃ mani padme hūṃ written in ancient Tibetan characters. To the practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism the repeating of this mantra brings spiritual merit.

The turning of the mani wheel increases the repetition and brings greater merit. mani wheels are a common element of most Tibetan monasteries, and Meru Nyingpa contains a variety.

Dzambhala Lhakhang, Ṃani Wheel, and Store

(MN003, MN004, MN005, MN006)

Just past the entrance mani wheels is a large mani wheel that is about two meters high and one meter in diameter which was set in its place by the Tibet Heritage Fund in 1999.

It marks the entrance to the Dzambhala Lhakhang, the oldest structure at Meru Nyingpa. Next to the entrance is a small store currently run by the Meru Sarpa monks who also maintain the Dzambhala Lhakhang.

Before 1959 this room originally served as a tsatsa room.29 In this room tsatsas were produced and stored. tsatsa were used by monks and lay persons to gain merit by placing them inside Buddhist statues.

During the traditional construction of a Tibetan temple, tsatsas were placed in the hollow spaces above the cantilevering cornices of the temple interior.30

The Dzambhala Lhakhang entrance faces east and steps down below the main alley level to provide access to the chapel (figure 11). The main chapel is composed of a small shrine room encircled by a circumambulatory corridor occupying a 7 x 8 meter space. The main images in the shrine room include Dzam bha la, the Protector of Wealth, Dpakara, the past Buddha Illuminator, and the eight main bodhisattvas all within respective wooden frames.

Tibetan Buddhists always move clockwise around a circumambulatory corridor entering on the left and exiting from the right. The walls of the circumambulatory corridor are covered in a continuous mural of the Thousand Buddhas. On the west wall of the chapel at the end of the circumambulation circuit is a mural painting of Khri Ral pa can who consecrated this chapel in the ninth century.31 The architecture of this space is described as Yarlung pertaining to the era of the early kings of Tibet and is characterized by the low ceiling and thick, heavy beams overhead.32 Adjacent to the mural of Khri Ral pa can is the main door which exits back out to the main entrance alley of the Meru Nyingpa complex.

Pelgön Shrine Room

(MN082, MN082, MN084)

Stepping back into the alley and looking back towards the entrance there are a set of stone stairs just behind the mani wheels that lead up to First floor gallery of the west wing of the surrounding residential buildings.

At the top of these stairs and to the north is the Pelgön or “Glorious Protector” Shrine room sitting directly over top of the Dzambhala Lhakhang.

The exterior walls of this Shrine room are covered in line drawn murals on a black background which stand out distinctly from the predominantly white walls of the rest of the monastery (figure 12).

The predominance of black on these walls may signify the color commonly associated with the chief protector deity Pelgön to whom the shrine is dedicated.

Stepping inside the Shrine room there are three stone steps that lead up to the raised floor that covers the majority of the space.

On the left side of this space are statues of Pelgön and the year round offering cakes, which are small offering sculptures traditionally made from yak butter or barley dough and consecrated to Buddhist deities.

In the center of this space are three clay statues including Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoché), historically noted for establishing the Nyingmapa, the first school of Tibetan Buddhism. Also represented here is Gürgyigön, the Savior of Tents and the principle of all protectors of Buddhist teachings, and an image of the Mistress of the Desire Realm Goddess.33 Above this central space is a small structure incorporating clerestory windows. Clerestory light from the roof illuminates the central Buddhist figures in the room.

The window frames can each be opened to allow air flow from the roof. A smaller light well projects from a small room to the back of the shrine. Clerestory lighting is common in shrine rooms and especially main temples as a means of illuminating the deities that are represented in that space.34

Pelgön Incense Burner, Shrine Kitchen and Shrine Keeper’s Room

(MN100, MN081, MN080)

Stepping outside of the Pelgön shrine and looking to the left (north) is an incense burner built into the wall and projecting through the ceiling to the roof. Juniper branches and barley flour (tsampa) are stored in an alcove next to the burner for monks and pilgrims to feed the fire. Adjacent to the burner is the kitchen for theGongkar Chödé monks of the Pelgön shrine as is evident by the defunct chimney flue in the south wall.

At the end of this gallery hall is a room that is raised to a mezzanine level over top of the main entrance to Meru Nyingpa and connects the west residential wing with the central temple but does not allow entry into the temple space. This small room serves as the quarters of the monk who attends to the Pelgön shrine room. 'Because this room rises above the level of the gallery, a small opening occurs over top of the entrance allowing light and ventilation into the hallway. Since Meru Nyingpa is laid out symmetrically an identical room exists on the east residential wing as well.

Lay Bathrooms

(MN091, MN090)

Lining the west, south and east wing buildings are doorways to more residential quarters which prior to 1959 were primarily the monks’ quarters intermixed with various storage rooms. The points where the wings meet at the southeast and southwest corners are occupied by the communal bathrooms which are basic shaft-type drop pits with cleanout accesses to the south alleyway. The Tibet Heritage Fund installed proper fixtures to replace the basic holes in the floors that pre-existed.35

Roof Access

(MN104, MN105, MN117)

Each wing has one access ladder to the roof although the western wing access is currently blocked up.

All spaces within the monastery constitute usable space including the roof. Currently the roof is used for solar kettle heaters that are popular in Lhasa today. A heater is basically constructed from a frame of welded steel rods that support the kettle.

A large reflector is attached to the frame that captures the powerful rays from the ever present Tibetan sun.

Upper and Lower Level Living Quarters

(MN011-22,23,36)

Each residential wing also contains a set of stone stairs down to the courtyard.

Here the ground level residences open directly onto the courtyard space. At one time the rooms that ring the courtyard at ground level served a myriad of functions.

Most of the upper-level rooms were offered as living quarters for the monks from the respective regional houses during the major festivals like the Great Prayer Festival of Mönlam and the Communal Worship Festival.

When these rooms were not inhabited by monks they were rented out to Bhutanese,

A mdoor Lhokha woolen cloth sellers. Rooms that were not used as residences were used as storage for drums and other musical instruments for festivals and processions, foodstuffs such as barley flour, tea, salt and rice, or grounds keeping equipment.36 Currently all of these rooms are occupied by lay residents.

An Exploration of the Main Courtyard

(MN038, MN043, MN041, MN040, MN039, MN142)

The courtyard space is commonly accessible from all doorway portals, staircases and ground floor entry points of the entire monastic complex. Starting again from the main entrance in the northwest corner of the complex, the narrow entrance corridor cuts between the west residential wing and the main temple and continues straight into the west end of the courtyard.

Here the compressed entry corridor opens to a communal space that separates the south residential wing from the central temple. Within the central open area of the courtyard is a large incense burner that is usually kept burning throughout the day with offerings of fumigation offering (sang) and barley flour (figure 13).

During festivals this large burner covers the entire complex with a thick aromatic smoke from the offerings of many pilgrims who stop here on their journeys to Lhasa. In the northwest corner of the courtyard is a stone hearth used to fire the large copper cauldrons of rice and tea used to feed the masses of pilgrims during the festivals such as Mönlam.

A water tap and pump are made available in the eastern end of the courtyard. Apparently a well previously existed in this location that likely gathered its water from the suppressed Lake Wothang below. The trunk of a tree grows out of the stone paving near the water taps and still sprouts a few green leaves on its scant branches.

A cypress or willow tree is a common element of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, symbolizing the bodhi tree under which the Buddha Śākyamuni received enlightenment.37 The courtyard also gives access to a corridor on the east side of the complex that mirrors the western entrance corridor. The eastern corridor leads to a blockaded entrance of the same size and decoration as the main northwestern entrance portal.

In earlier times, pilgrims coming to visit the monastery could also enter through the northeastern door. Later, however, the eastern door was permanently closed, and the pilgrims had to go through the western door of the northern entrance. On auspicious days when traffic is heavy the western entrance corridor can become quite difficult to navigate.38

An Exploration of the Central Temple

The Main temple stands to the north and center of the complex. It is a three-story structure with a rooftop chapel built on top of the north central portion.

The temple building can be divided up into three main parts consisting of a central core with two flanking wings all unified within a single massive structure.

The central portion is primarily the religious core of the temple housing the assembly hall, associated chapels and other rooms accommodating religious functions.

The wings are primarily residences for lay people and monks, storage rooms, kitchen facilities and monks’ toilet facilities and washrooms.

Main Entrance Portico

(MN058, MN057, MN075)

The main temple’s primary entrance is on the south façade which is exposed to the open courtyard (figure 14). The courtyard incense burner stands nearly on a centerline axis with the stone stairs that lead up to the entrance portico.

The central bay of the main temple projects into the courtyard and includes the entrance portico and balcony of the room over the entrance.

Immediately east of the steps going up to the entrance portico are a set of covered mani wheels similar to those at the main northeast entrance. The floor of the portico stands about one and a half meters above the courtyard and has a cantilevered structure supporting a low wall that encloses the perimeter. The portico supports the balcony overhead with four large compound columns that resemble the large columns at the main entrance to the Jokhang.

Each column type has a maṇḍala-like cross section whereby each face has a stepped back pattern. The maṇḍala cross section is the result of the column being composed of bundles of smaller columns with the whole composition further accentuated by gold bands either painted around the shaft or actually constructed from gilded metal.

Columns of maṇḍala cross section are typical of most monastic portico entrances such as those found at Zhidé and the temples of Sera and Drepung.39 Just behind the columns are two large mani wheels symmetrically placed on either side of the entrance axis.

These would be kept perpetually spinning by pilgrims or monks before entering the main temple. The portico walls are covered in murals of the Four Guardian Kings who are the protectors of the four directions, commonly found at the entrance to monasteries and temples.40

From the portico different routes may be taken to access the temple. To the left are a short set of stone stairs leading to a room in the west wing that was once the residence of the monk official that lead the prayer assemblies and the disciplinary monk but is currently occupied by the shrine keeper for the Central shrine room.41 To the right are a short set of stone stairs leading to a small landing.

From this landing there is access to a room in the east wing that was previously used as the living quarters of the attendant of the Nechung protector deity. Also from this landing is a stair ladder that leads to the upper levels. Straight ahead through the portico is the portal to the central assembly hall, richly decorated in a sculpted wooden frame.

The Assembly Hall

(MN074)

Stepping over the threshold of the assembly hall one enters a darkened space of intricate detail and rich colors. Immediately on the left and right are two more large mani wheels. Immediately ahead is the central space where the monks assemble and recite the Buddhist sūtras. Around this central area is a inner circumambulation path (nangkor) which follows around the central chanting space of the monks.

Typical of the assembly hall space is a low ceiling around the perimeter and a tall, multi-story central space, often lit by clerestory windows near the raised ceiling (figure 15). This space is marked by a grid work of columns with shorter columns supporting the surrounding low ceiling and taller columns reaching up to the raised ceiling.

The light from the clerestory illuminates the center of the room where a central shrine or statue is placed.

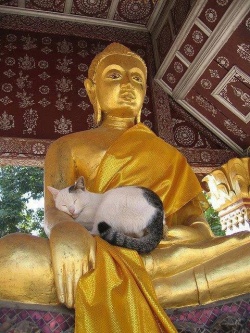

All around on the walls are a myriad of mural paintings depicting protector deities with Dorjé Drakden being the central figure and to whom this main temple is consecrated (figure 2). On the walls of the central skylight are paintings depicting the champions of Tibetan Buddhism:

Tsongkhapa, the founder of the dominant Gelukpa school; Atiśa, an eleventh-century monk who is historically noted as the principal Indian figure in re-introducing Buddhism to Tibet during the second diffusion of Buddhism;

Guru Rinpoché (padmasambhava) an eighth-century monk from Swat who was historically responsible for first instituting Buddhism in Tibet;

and Khri Srong lde btsan, the thirty-eighth king of Tibet and one of the Three Dharma Kings, also responsible for bringing Buddhism to Tibet. From the large multistory columns hang tangka paintings and long column hangings of brightly colored brocade.

On the north wall of the assembly hall are a series of shrines and offering devices. Offerings can be made by placing money on or near the shrine or by pouring chang or offering beer into the chang bowls in front of the shrines.

At times the main central shrine may be a statue of the eleven headed Avalokiteśvara or the four armed Avalokiteśvara, the main bodhisattva and protector of Buddhism in Tibet.42

When these images are not found in the center of the shrine space, their wooden cases are placed in the northwest and northeast corners of the assembly hall. In the center of the north wall are a short set of stairs leading to an inner chapel beyond the assembly hall. To the right of this entrance is a statue image and tangka of Pelden Lhamo, protector deity of Buddhist teachings depicted in blue and to the left is a statue and tangka of Dorjé Drakden depicted in red.

The Inner Chapel

(MN072)

The northern inner chapel is partially obscured by the shrine to the two protector deities but would otherwise be open to the assembly hall.

There is a large copper butter lamp tub in the center of this small chapel which serves to dispel ignorance and illuminate the mind.

This small rectangular space is filled with statues and Buddhist images to the left and right and on the north wall in front of the stair entrance. The main image in the center of the north wall is a large Guru Rinpoché sitting within a glass case.

To the left and right of this image are various statues in their respective glass cases as well as depictions of past gurus, lamas and protectors. Above these cases filling the space to the ceiling are glass cases for Buddhist texts.

To the left (west) of the inner chapel is a small storage room for butter, cheese and barley flour. To the right is a doorway to a multi-story wooden stair ladder that leads to the penthouse chapel on the roof.43

Eastern Wing Access from the Assembly Hall

(MN067 – 70)

Within the main assembly hall space there is also access to the eastern wing from a small set of stairs on the northeastern wall. A doorway leads to rooms that cover the majority of the first floor of the east wing.

This long space is primarily used to store the large drums and instruments of the ceremonies that take place in the assembly hall.

Structurally this space is supported by a single row of columns supporting a beam running the length of the wing. This construction is reflected in the other levels of both wings.

Second Floor Lightwell Corridor

(MN120)

The second level of the central core of the temple is accessed by the stair ladder to the east of the main entrance portico. This ladder leads directly to an open space corridor that surrounds the lightwell structure of the assembly hall atrium. From this corridor there is access to the main room built over the south portico (MN111).

This is a large room with a balcony overlooking the courtyard. Traditionally this room would be used as the official monastic business office.

At Meru Nyingpa this room was used as the residence of the abbot of the central temple, but is currently used as a meeting room for higher level monks or as a reception room for distinguished guests.44

The open corridor is bounded on one side by the clerestory windows allowing light and air flow into the central assembly hall space. The lightwell corridor also affords access to the east and west wings.

The west wing access leads to storage rooms and shelters for pilgrims during festivals. Also on the west side of the lightwell corridor is access to the southwest room which is currently the residence of the oldest and most learned historian and shrine keeper of the main shrine room in the assembly hall. The east access from the lightwell corridor leads to the main monks’ kitchen and solar shower rooms.

Also accessible is the southeast corner room which was the residence of the Nechung lama and currently used as a monks’ residence. Mixed in with these religiously oriented spaces are lay persons’ residences in the east wing also accessible from the lightwell corridor. At the north end of the east corridor is a wooden stair ladder leading up to the roof where the Rooftop chapel is situated (figure 16).45

The Rooftop Chapel

(MN131)

The central room of the rooftop chapel was once the residential quarters of the succession of Dalai Lamas but later became the quarters of the Nechung Oracle. Currently it is a shrine room whose main shrines are laid out upon the north wall.

Here there is a collection of the complete works of Tsongkhapa, a throne to the Dalai Lamas and a tangka of the Buddha Amitayus.46 On the walls are murals that were beautifully restored by the Tibet Heritage Fund in 1999. Offering bowls and troughs and a large drum and cymbals are present as well. The south wall of the shrine room consists of a series of windows overlooking the roof of the temple.

A short hall leads to the ladder stairs that descend to the first floor inner chapel.

Across this hall from the shrine room is a small room used as a monastic residence.

At the end of the hall is the main toilet facility for the main temple which was upgraded with porcelain fixtures by the Tibet Heritage Fund.

Also accessible from the hallway is the roof of the main temple.

The main roof is another common meeting area of pilgrims during festivals during which tarps may be strung across to provide temporary shelters during the rainy summer months (figure 16).

Ground Floor Rooms of the Central Temple Wings

The ground floor rooms of the main temple wings are accessible from the east and west corridors connected to the courtyard. These rooms served a variety of monastic purposes.

One room on the west side opens to a set of stone stairs that provides the only access to the west wing’s first floor. This long space was used as a monastic kitchen but now serves as lay residences.

The southeast corner room was once the residence of the Meru Sarpa monks who attended the Dzambhala Lhakhang directly across the west entrance corridor. Most of these ground-level rooms are currently lay residences.47

[28] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 73.

[29] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[30] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 38.

[31] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[32] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[33] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[34] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[35] Lhasa Architecture, THF.

[36] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[37] Françoise Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries in Tibet,” in The Buddhist Monastery: A Cross-Cultural Survey, ed. Pierre Pichard and François Lagirarde (Paris: Ecole française d’extrême-orient, 2003), 297.

[38] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[39] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[40] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[41] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[42] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 103.

[43] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[44] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[45] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[46] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[47] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

Buddhist Monastery Construction

Form

A typical traditional Tibetan building, whether it is a monastic temple or secular residence, is basically composed of a masonry shell with interior timber framing. Early Tibetan building forms were modeled on examples from India, China and Nepal, with which Tibet had extensive connections. Unlike the sculpted architectural forms of India and the imperial detailed structures of China, Tibetan buildings were externally austere.

Tibetan buildings are characterized by a rough form that blends with the surrounding environment. These structures are of a monumental scale, with rectangular layout, battered, trapezoidal walls and flat roofs.48 The walls have externally whitewashed surfaces with minimal decoration reserved mainly for windows, doors and upper parts of the building.

The interior of religious buildings contrasts dramatically with the severity of the exterior. Inside are myriad colors coming from wall hangings, tangka paintings, wall murals, sculptures and shrines. Interior spaces are commonly dark with lit areas emphasizing shrines and statues. A pervading red color helps to create a warm, dark interior contrasting with the intense, brightly lit white exterior.

Colors

A common palette of colors can be found in the typical Tibetan monastery.

White is the color that overwhelmingly describes the exterior of just about any Tibetan building. This is a result of the walls being doused in buckets of whitewash made from lime.

Some older monastic buildings may be colored in a yellow-ochre color.49 Splashes of blue, red, yellow and white adorn the curtains of windows and doors.

The minimal use of color on the exterior of a Tibetan temple is balanced by the explosion of color on the interior.

The predominant color is red, which is the background color on the columns, main beams and lower parts of the walls.

The exposed secondary beams are usually painted blue, but can occasionally be painted green. The ceiling planks in between these beams are a bright yellow.

Sometimes the ceiling appears to be painted black, which is the result of numerous butter lamps that have been burning for many years. Otherwise a rainbow of colors, including silver and gold, fills in the details of most artistic elements within the monastic interior. The roofs of important buildings may be copper gilded or painted yellow to signify a sacred space below, such as a large Buddha statue or important shrine.

Materials

Tibetan monasterys were constructed using three primary materials: stone, timber and earth. Early structures were made from sun dried brick or rammed earth walls.50 Timber is only abundantly available in the southeast, where there is the presence of some completely wooden structures. Timber may also be transported over the mountains from Bhutan or Sikkim.

Poplar, willow, cypress and juniper are common types of wood used in construction from these regions.51 The majority of monastic buildings in central and western Tibet primarily use timber as the interior framing material.

Timber beams and columns tie directly in with the heavy masonry walls of the structural shell. Other uses of timber can be found in some roofs that are supported by the Chinese system of dou gong bracketing.

The presence of complicated wooden bracketing is evidence of Chinese influence that was especially strong during the Tang Dynasty.52

Stone is the preferred construction medium, which is evident from the heavy masonry walls found in most monastic buildings.

Early masonry walls were composed of stones collected from the rivers or mountain sides, instead of being quarried out of the ground as they are today.

Large blocks formed thick foundations and walls with a slight batter.53 Smaller chinking stones or a clay and sand mixture served as mortar (figure 17).54

Massive walls were built in rows of blocks that curve upward on each end to compensate for the weight of the stone as well as provide suitable resistance to earthquakes, which would occur quite frequently in some areas of the Tibetan Plateau.55

Foundations

The process by which a Tibetan monastic temple is constructed begins with a geomantic survey and ritual cleansing of the site. The master builder (wuchen) is responsible for the building layout.56 Plans of the temple are not pre-drawn on parchment, but rather they are laid out directly on the site by drawing lines in the earth.57

The master builder calculates wall and foundation widths based on the determined height of the building.58 A relatively shallow foundation of less than half a meter is dug out of the earth. The width of the foundation is approximately 1.5 times that of the wall base.59 The foundations are filled in and packed down firmly. The traditional method of packing a foundation was achieved by building workers (sengdo), who would continually lift and drop heavy stones on top of a freshly laid foundation.60

Walls

Main load bearing walls are then built over the foundation, usually with a wall base of 1 to 1.5 meters. These walls are composed of two layers of heavy masonry with an inner layer of crushed stone and clay binding together the entire construction. Walls are built layer by layer of rows of heavy stone blocks. Interior walls have an inner wall that is vertically straight while the outer wall has an upward slope creating a battered wall that provides protection from earthquakes.61

Columns

After the construction of the main walls, base supports are placed beneath the locations for the interior columns.62 The interior layout is punctuated by a grid work of timber columns. The spacing between columns is contingent upon the length of the timber beams they support which ranges from 2.0 to 2.2 m.63 The column shaft is traditionally hewn from juniper with an average cross section of 200 x 200 mm. Long column shafts that support the high ceiling of the central temple assembly room are composed of two sections.

The complex capital is traditionally carved from pine with an average cross section of 150 x 210 mm. The whole column shaft and capital system is pre-assembled upside down in a workshop before being brought to the site.

The connections between beam and column members are achieved through square slotted joints or round pegs.64 Columns found within the temple can have differing cross sectional forms. Common columns found in storerooms or monks’ residences may be simply cylindrical with a circular cross section.

Columns found in more reverential spaces such as those found in the temples will have a square cross section. These columns taper to a smaller cross section as they rise. A type of compound column may be found in the entrance portico of a main temple. These columns have a cross section resembling a maṇḍala form being composed of bundles of smaller columns (figure 18).65

Column types can change according to the use of the room. The more elaborately decorated columns of the compound type are typically found at the main entrance portico of a temple. Inside the temple can be found a forest of square tapering columns with large capitals and carved decorations.

Taller versions of these are usually located in the center of the assembly hall where there may exist a multi-storied space with clerestory windows to illuminate a large statue of the Buddha or murals that have been painted on the upper parts of the walls. Side chapels and altar rooms will have smaller versions of these tapering columns.

Residential cells, kitchens and some monastic storerooms will have simpler square or round columns with minimal painted decoration. Basic storage and utility rooms may have plain unpainted round or square columns.

System of Column Capitals

The capital of a traditional Tibetan column is a layered structure. It is a feature of Tibetan architecture that is characteristically unique and recognizable in the monasteries of the Himalayan region. The composition of a Tibetan capital begins with a small square of wood (Dre) that separates the top of the column shaft from the capital. The capital contains two distinct curvilinear forms. The lower is called the small bow and the upper is the long bow.

The small bow is basically a small bracket with a length about twice the column width that initiates the transition between pillar shaft and capital. It is usually carved or painted with decorations. Above there may be an optional block separating the small bow from the long bow. The long bow is the more ornately carved of the two bracket members.

It is a much longer bracket which at times may be as long as the column is tall. It is usually carved in a cloud type pattern which gives an undulating almost serrated bottom edge. The long bow faces are usually brightly painted in rich greens, blues, yellows and white with a central figure that may be painted in gold (figure 19).66

Beams and Ceilings

The main beam sits on top of the long bow. This is usually made from pine and has an average rectangular cross section of 150 x 120 mm. The beams in one room are usually laid out perpendicular to beams in an adjoining room for overall structural rigidity.67 Above the main beam is a system of ceiling brackets forming a layered cornice.

In their most complex form this system may contain several layers that cantilever outwards, each carved in a particular design.68 This cornice work supports a secondary layer of circular cross beams that are laid perpendicular to the main. These are laid close together and above them are placed small ceiling members called ceiling planks.

The ceiling planks are small round members that are laid in a characteristically herringbone pattern (figure 19).69 Traditionally the empty spaces formed by the cantilevering cornice structure above the main beam would be filled with “treasures” of silk, cloth, grain or tsatsas. Buddhist belief entrusts that these votive items would help prevent disharmony in the assembly hall.70

Ceiling Plank Stones and Ārka

River stones are laid on top of the ceiling planks to form a base layer for the roof or flooring material of the above level. Smaller stones are laid in between the larger stones to create a compact layer. The remaining gaps are filled in with gravel.71

On top of this is a layer of yellow mud that is about 100 mm thick. This layered mixture of mud and stone serves as the base for a traditional arka roof.

This layered mixture of mud and stone serves as the base for a traditional arka roof.

A coarse clay and rock mixture is laid down and then manually stamped to form a firm layer. A finer mixture of clay is applied over the base layer and also stamped repeatedly until firm.

The stamping of this surface usually involves a group of men and women laborers who chant and keep cadence with their flat stone for evening a floor under construction (bokto). After the roof is hand stamped to a smooth and durable finish, the surface is impregnated with a waterproofing material made from tree bark extracts and a resin from rapeseed oil.

The entire surface of a roof is covered in arka including the parapets and edges to create smooth rounded surfaces.72 The entire construction process of a typical Tibetan building is nicely animated on the Tibet Heritage Fund website.

[48] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 40-1.

[49] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 52.

[50] Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries,” 288.

[51] Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries,” 289.

[52] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 41.

[53] Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries,” 289.

[54] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[55] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[56] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 44.

[57] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 35.

[58] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 44.

[59] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[60] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[61] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[62] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[63] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[64] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[65] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[66] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[67] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[68] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[69] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[70] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 38.

[71] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[72] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

Meru Nyingpa Architectural Detail

Pembe Frieze

Meru Nyingpa exhibits a number of details of construction that are unique to Tibetan architecture. Located near the top of the wall of the main temple is a dark maroon band called the pembe frieze. This distinct feature is composed of thin branches of a tamarisk bush cut to short, even lengths and attached to the main wall in bundles with the ends sticking out. To this rough surface there are fastened gilded medallions of Buddhist iconography (figures 17, 20). The pembe frieze is reserved for religious and government buildings and is a distinguishing feature in a sea of whitewashed buildings in a Tibetan city or town.73

Pebur/Karma Courses

The pembe frieze is separated by a thin horizontal course composed of two layers. These bands are visually identifiable as a layer of squares and a layer of circles. The square band is composed of short wooden blocks called pebur which are constructed into the wall and protrude out beyond the wall surface displaying a row of square ends. Its sister course is a wooden frame that is painted with the karma pattern which is composed of a row of white circles resembling rafter ends (figures 17, 20). This band is nailed into the pembe frieze with long wooden nails.

There may be several courses of these bands that divide up the pembe frieze and ultimately form its crowning cornice just under the roof parapet cap.74 Each course is usually covered by a small slanted awning of slate shingles. The north façade of the Meru Nyingpa temple exhibits three courses of pebur/karma bands over top of a larger course consisting of dou gong brackets supporting a larger slate covered awning (figure 22).

This bracketed course separates the lower portion of the central wall from the north wall of the rooftop chapel. The upper three bands continue around the rooftop chapel walls which are primarily covered in pembe frieze. The wall of the main temple’s north façade is painted a dark maroon to match the color of the pembe frieze. This wall projects into the north alley adjacent to the temple to further implicate its significance as a religious edifice of high stature ( figure 16).

Flat Rooftops with Low Parapets

All the walls of the monastery, including the outer residential buildings, are topped by a low parapet. Its smooth rounded cap follows the edges of the buildings. The characteristically flat roofs are sloped to carry water away to the edges. Drainpipes carry water off of the main temple roof where the pembe frieze is occasionally punctured by triangular openings that allow for the drainpipes to emerge (figure 21). Copper and brass drainpipes carry water to the sewer system below the courtyard.

Portals

Another distinguishing feature of a Tibetan building is the treatment of the openings for doors and windows. These portals are outlined with a thick black border frame. This frame is made from a clay that is thickly applied to the masonry wall after placement of the windows or doors.

It has a distinct trapezoidal form making the portals appear much larger than their openings. It has been suggested that this detailing may act as a heat collector to warm the air before it flows to the inside of the building.

This treatment would have been more effective for older window constructions that employed shutters as window coverings prior to the use of window glass.75 Constructed over top of each window on the main temple is a cantilevered shading structure.

A small slate shingle awning is supported on two layers of square timber elements that protrude from the wall face (figure 23). This structure is usually hidden behind a short curtain that is hung just below the overhanging slate shingles.

A large bracketed awning covers the door frame of the main northwest entrance. The imposing structure is a signal to anyone approaching from the north or east alley that there is an entrance to some religious edifice of great importance. Two large wooden doors painted with depictions of flayed human skins open inward to the northeast entrance alley. On each is attached a semi-spherical door ring made of engraved metal. Similarly engraved hinge straps also adorn the exterior.

Textiles

Textiles are commonly used as an architectural treatment of exterior and interior edges such as door and window awnings or the bottoms of main beams. Curtains hanging over doorways and underneath balconies create a flowing kinetic surface to the walls and spaces of the temple building (figures 14, 15). Curtains are commonly hung within the doorway portal of residential cells obscuring the wooden door behind.

Carved patterns

A variety of carved patterns can be found in the details of doorways, column capitals and some window frames. Usually these are bands of decoration within a layering of details. Two common decorative frame borders include a lotus flower motif and a triangular pattern of tiny cubes cut in relief called “chötsek.”76

Long bow and short bow capital elements are carved with cloud and floral motifs giving the impression of weightlessness (figure 19).77

Gyeltsen

On the roof of the main temple may be found a number of tall cylindrical structures called gyeltsen. The gyeltsen are literally “victory banners” signifying the victory of Buddhism (figures 16, 24)78. These banners fly above the parapet wall and serve to keep evil away from the monastery. They are usually located in the corners of the parapet or gaps in the parapet where the parapet wall ends. There are special receptacle blocks in the parapet walls to which the gyeltsen are attached.

The main body is supported on a flagstaff of wood and can take a variety of forms. Though the main form is cylindrical the material can vary from curtain cloth to yak hair to a gilded metal. Some types are built in short sections that are loosely fitted to the pole so that they may blow about in the wind.

Another type is bound in gilded metal bands with metal bosses attached. Each type is usually crowned with a decorative motif. In addition to the gyeltsen banners the roof of the upper chapel also contains a central lotus statue constructed of gilded copper plating. The gyeltsen and lotus statue stand out in a sea of flat top roofs to signify the presence of a Buddhist monastery within the Barkor neighborhood of old Lhasa.

[73] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 49.

[74] Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang.”

[75] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 50.

[76] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 54.

[77] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 57.

[78] Sarat Chandra Das, A Tibetan-English Dictionary, (Botilal Banarsidass Indological Publishers, 1979), 313-4.

Notes

[1] Victor Chan, Tibet Handbook (Chico, CA: Moon Publications, 1994), 63.

[2] André Alexander, personal communication, 5 October 2005.

[3] Red and white were colors of great significance in pre-Buddhist Tibetan culture. Red meat and white dairy products were the main staples that sustained the lives of early Tibetans. Meat ceremonies (mardön) and dairy ceremonies (kardön) were common amongst nomadic cultures (Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Townscape, (London: Serindia, 2001), 51.). White also came to represent peacefulness, cleanliness, and good fortune. Red represented power, dignity, and honor in memory of past heroes and leaders (Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 51). Red was also the color representing the king and his court, and was revealed through red clothing, red flags, and red palaces and buildings.

In religious practices white offering cakes (torma) were offered to the Buddha while red offering cakes were offered to the protector deities (Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 51).

The respect given to the colors of red and white seemed to have been represented in the two chapels built just east of the Jokhang. Perhaps the White Chapel, or “Karu” as mentioned above, was built to honor the Buddha while “Marru,” or the Red Chapel, served as a protector chapel referred to as the Meru Chökhang by Khri Ral pa can in the ninth century (André Alexander, “A Clear Lamp Illuminating The Significance And Origin Of Historic Buildings And Monuments In Lhasa Barkor Street,” in The Old City of Lhasa, ed. John Harrison and Pimpim de Azevedo, [[[Wikipedia:Berlin|Berlin]]: Tibet Heritage Fund, 1999]).

[4] David Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, A Synoptic and Map-Based Introduction to the Rooms In the Meru Nyingpa Monastic Complex, (Charlottesville, VA: Tibetan and Himalayan Library, 2003).

[5] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[6] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[7] André Alexander, personal communication, 5 October 2005.

[8] Giuseppe Tucci, Tibet: Land of Snow, trans. J. E. Stapleton Driver, (London: P. Elek., 1973), 69.

[9] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[10] David L. Snellgrove and Hugh Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, (Boston; London: Shambhala, 1995), 130.

[11] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 119.

[12] André Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang,” Tibet Heritage Fund, http://www.tibetheritagefund.org/media/download/Articolo_8_Alexander.pdf. Retrieved 19 October 2005.

[13] “Nechung - The State Oracle of Tibet,” The Office of Tibet, http://www.tibet.com/Buddhism/nechung_hh.html. Retrieved 16 November 2005.

[14] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[15] André Alexander, personal communication, 5 October 2005.

[16] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[17] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 119.

[18] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[19] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[20] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[21] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[22] Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang.”

[23] “Meru Nyingba Monastery,” Tibet Heritage Fund, http://www.asianart.com/lhasa_restoration/76houses/merunyingba/index.html. Retrieved 10 October 2005.

[24] “Meru Nyingba Monastary.”

[25] Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang.”

[26] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple: Manual of Tibetan Monastic Customs, Art, Building, and Celebrations (Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1979), 39.

[27] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 40.

[28] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 73.

[29] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[30] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 38.

[31] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[32] Chan, Tibet Handbook, 120.

[33] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[34] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[35] Lhasa Architecture, THF.

[36] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[37] Françoise Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries in Tibet,” in The Buddhist Monastery: A Cross-Cultural Survey, ed. Pierre Pichard and François Lagirarde (Paris: Ecole française d’extrême-orient, 2003), 297.

[38] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[39] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[40] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[41] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[42] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 103.

[43] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[44] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[45] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[46] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[47] Germano, Tsering Gyalpo and Buchong, Introduction to the Rooms.

[48] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 40-1.

[49] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 52.

[50] Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries,” 288.

[51] Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries,” 289.

[52] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 41.

[53] Pommaret, “Buddhist Monasteries,” 289.

[54] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[55] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[56] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 44.

[57] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 35.

[58] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 44.

[59] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[60] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[61] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[62] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[63] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 45.

[64] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[65] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[66] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[67] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[68] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[69] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[70] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 38.

[71] Thubten Legshay Gyatsho, Gateway to the Temple, 36.

[72] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 46.

[73] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 49.

[74] Alexander, “The Lhasa Jokhang.”

[75] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 50.

[76] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 54.

[77] Larsen, Lhasa Atlas, 57.

[78] Sarat Chandra Das, A Tibetan-English Dictionary, (Botilal Banarsidass Indological Publishers, 1979), 313-4.