Leaving a Guru – Discriminating bad from good Gurus

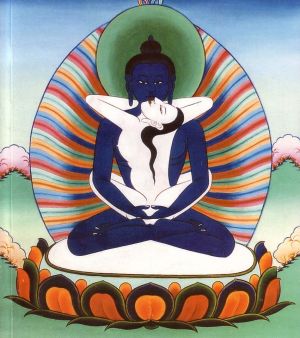

From The Kalachakra Tantra

Source: Ornament of Stainless Light – An Exposition of the Kalachakra Tantra by Khedrup Norsang Gyatso, pp. 214–216, translated by Gavin Kilty

Note: Khedrup Norsang Gyatso was a student of the First Dalai Lama and a teacher of the Second Dalai Lama. He is a lineage master of many practice lineages, is a Gelugpa but practiced teachings also from other schools, e.g. Kagyue Mahamudra teachings.

Characteristics of those unsuitable to be gurus

The third verse of the Initiations chapter says:

Proud, ruled by anger, and lacking vows, greedy, without knowledge, working to deceive disciples, a mind that has fallen from great bliss, without initiation, totally attached to wealth, unaware, of harsh and coarse words, filled with carnal desire, the wise disciples should abandon taking such people as causes of complete enlightenment as they would abandon hell.

People with such faults are not fit to be relied upon as gurus in the Vajra Vehicle. Even if one takes such a person as a guru and requests initiations and so forth, there can be no meaningful receiving of the initiation. Moreover one will become infected by a measure of his faults and fall from all elevated

status in this and future lives. Most of the above verse is easy to Understand. »Without knowledge« means to be without the essential teachings on the six-branched yoga, for example. »Working to deceive his disciple« means to delude disciples by telling lies. »A mind that has fallen from the great bliss,

without initiation« means that without having received the initiation he is bestowing, he nevertheless teaches it to others. »Filled with carnal desire« means working only for the pleasure gained from the sexual union of the two organs. Therefore the way to rely upon a guru is firstly to know the

characteristics worthy and unworthy of devotion and then to examine thoroughly who is and who is not fit to be a guru. The Great Commentary says on the second verse of the Initiations chapter:

Disciples who wish to gain worldly and nonworldly powers by way of mantra should first devote themselves to a guru. Furthermore one should examine the vajra master thoroughly. One should thoroughly examine his words. Otherwise, relying upon a guru unexamined, the disciples’ dharma will be perverse, and perverse dharma will send them to hell.

Also the Paramartha Seva says:

He, omniscient in the complete Vajra Vehicle, has said that every wished-for siddhi follows the master. If perfect disciples examine the master, therefore, as they would gold, they will not accrue even the tiniest of faults.

However what should one do if one already regards as a guru someone endowed with those unworthy characteristics? The Great Commentary says:

In mantra, even though one has taken as a guru a person with the faults of pride and so forth, wise disciples, meaning those of intelligence, will abandon him as a cause of complete enlightenment as they would abandon hell.

Also:

Because of these words, even though he has been taken as a guru, if he does these wrong deeds, disciples who strive for freedom should leave him.

A passage quoted in the Great Commentary says:

Without compassion, angry and malicious, arrogant, grasping, uncontrolled, and boastful, the intelligent disciple will not take such a one as guru. Therefore, if one has taken someone with these faults as a guru, then this disciple who is seeking freedom should part company with him and not associate with him again. These quotes from the Great Commentary teach just this point and this point only. They do not teach that one should loose one’s faith due to seeing faults because, as it is so rightly said:

Once that is used as a reason and one casts off the undertaking of holding him as a guru and as a field of reverence, one opens up the opportunity for a root downfall to occur. One must learn, therefore, to distinguish what is to be developed from what is to be discarded.

Some explain the two instances of the phrase »taken as a guru« in the two Great Commentary passages above as applying to gurus taken by others.

It is advised to separate from wrong Gurus, because they lead the disciples to wrong paths. By following wrong teachers one corrupts and destroys the own spiritual life and especially all the future lifes. You’ll find good advice in Dza Patrul Rinpoche’s text: »The words of my perfect teachers« where he explains the dangers of following wrong Gurus. It covers most of the subjects and is very inspiring. Here is one example of four types of faulty teachers that should be avoided:

Patrul Rinpoche (from »Words of my Perfect Teacher

Teachers like the frog that lived in a well

Teachers of this kind lack any special qualities that might distinguish them from ordinary people. But other people put them up on a pedestal in blind faith, without examining them at all. Puffed up with pride by the profits and honours they receive, they are themselves quite unaware of the true qualities of great teachers. They are like the frog that lived in a well.

One day an old frog that had always lived in a well was visited by another frog who lived on the shores of the great ocean.

»Where are you from?« asked the frog that lived in the well.

»I come from the great ocean,« the visitor replied.

»How big is this ocean of yours?« asked the frog from the well.

»It is enormous,« replied the other.

»About a quarter the size of my well?« he asked.

»Oh! Bigger than that!« exclaimed the frog from the ocean.

»Half the size, then?«

»No, bigger than that!«

»So—the same size as the well?«

»No, no! Much, much bigger!«

»That’s impossible!« said the frog who lived in the well. »This I have to see for myself.«

So the two frogs set off together, and the story goes that when the frog who lived in the well saw the ocean, he fainted, his head split apart, and he died. And from the same text, »Words of my Perfect Teacher«, Dza Patrul Rinpoche:

The Great Master of Oddiyana warns:

No to examine the teacher Is like drinking poison; Not to examine the disciple Is like leaping from a precipice.

You place your trust in your spiritual teacher for all your future lives. It is he who will teach you what to do and what not to do. If you encounter a false spiritual friend without examining him properly, you will be throwing away the possibility a person with faith has to accumulate merits for a whole lifetime, and the freedoms and advantages of the human existence, you have now obtained will be wasted. It is like being killed by a venomous serpent coiled beneath a tree that you approached, thinking what you saw was just the tree’s cool shadow.

By not examining a teacher with great care The faithful waste their gathered merit. Like taking for the shadow of a tree a vicious snake, Beg, uiled, they lose the freedom they at last had found.

A prayer from Je Tsongkhapa

May I be cared for by true spiritual friends, filled with knowledge and insight, sense stilled, minds controlled, loving, compassionate, and with courage untiring in working for others.

May I never fall under sway of false teachers and misleading friends their flawed views of existence and nonexistence well outside the Buddhas intention. I pray that I listen insatiably to countless teachings at the feet of a master, single-handedly with logic unflawed, prizing open scriptures’ meanings.

AND

I pray that in no way I be misled by unwholesome friends and deceiving Mara but in care of true spiritual friends, complete the enlightened way. May I never fall under the sway of false teachers and misleading friends, their flawed views of existence and nonexistence well outside the Buddha’s intention.

May I bring to the path praised by the Buddha those lost and fallen onto wrong paths, swayed by deluded teachers and misleading friends. The head turned by dark forces hinders experience of the joyful festival that is the community of the Dharma life. May I never encounter misleading friends, in reality the cohorts of Mara.

from »The Splendor of an Autumn Moon : The Devotional Verse of Tsongkhapa«, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0861711920, translated by Gavin Kilty

Je Tsongkhapa, citing the Ornament for the Essence said:

»Distance yourself from Vajra Masters who are not keeping the three vows, who keep on with a root downfall, who are miserly with the Dharma, and who engage in actions that should be forsaken. Those who worship them go to hell and so on as a result.«

(see Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice by Tsongkhapa, ISBN 0861712900) - page page 46

A quote from chapter 10, »Relating to a Spiritual Teacher: Building a Healthy Relationship«, by Alexander Berzin:

»Some Westerners face similar situations with several of their spiritual teachers. For example, some famous masters disagree strongly about the status of a

controversial Dharma-protector and the consequences of propitiating it. They abuse their positions as spiritual mentors and, with threats of hell, forbid their disciples to have anything to do with teachers on the opposite side of the dispute. Other famous masters disagree violently over the identification of

the incarnation of the highest lamas of their lineage. A few have even taken police action against each other’s claims over inherited property. Sutra-level gurumeditation, as His Holiness the Dalai Lama has experienced, may help traumatized Western Dharma students to deal with these difficult, perplexing

circumstances. It may also help those who have been sexually abused by their spiritual teachers or exploited by them for power or money. It may apply as well to disciples of abusive teachers, who have not been personally maligned, but have been devastated by learning of the actions of their teachers.

Many disciples find such situations too difficult to handle, especially if they have already built disciple-mentor relationships with both parties in a dispute. The Abbreviated Kalachakra Tantra advised that if disciples find too many objective faults in their spiritual mentors and they can no longer

support close relationships with them, they need not continue studying with these teachers. They may keep a respectful distance, even if they have received highest tantra empowerments from them.«

For more see: Berzin, Alexander. Relating to a Spiritual Teacher: Building a Healthy Relationship. Ithaca, Snow Lion, 2000. Online at: http://www.berzinarchives.com/e-books/spir...l_teacher_c.htm

A quote from »The Teacher-Student-Realtionship«, Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, Snow Lion Publications, (or use: »Buddhist Ethics« [[[Treasury of Knowledge]]], Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye, Snow Lion Publications):

Avoiding Contrary, Harmful Companions 8.1 Obstructions of a harmful friend

»The harmful teacher is one of bad temperament, of little pure vision, great in dogmatism; he holds [his own view) as highest, praises himself, and denigrates others.«

In general, the nonspiritual teacher (mi-dge-ba'i bshes-gnyen) is a lama, teacher (mkhan-slob), dharma brother [or sister] (grogs-mched), and so forth—all those who are attached to the phenomena (snang) of this life, and who get involved in unvirtuous activity. Therefore, one must abandon the nonspiritual friend. In particular, although they have the manner of goodness in appearance, they cause you to be obstructed in your liberation.

The nonspiritual teacher has a bad temperament, little pure vision (dag-snang), is very dogmatic (phyogs-ris), holds as highest his view (lta-ba) as the

only dharma, praises himself, slanders others, implicitly denigrates and rejects others’ systems (lugs) of dharma, and slanders the lama—the true wisdom teacher—who bears the burden of benefiting others. If you associate with those who are of this type, then, because one follows and gets accustomed to the nonspiritual teacher and his approach, his faults stain you by extension, and your mindstream (rgyud) gradually becomes negative. Illustrating this point, it has been said in the Vinaya Scripture:

»A fish in front of a person is rotting and is tightly wrapped with kusha grass. If that [package] is not moved for a long time, the kusha itself also becomes like that. Like that [[[kusha grass]]], by following the sinful teacher, you will always become like him.«

Therefore, as it has been said in The Sutra of the True Dharma of Clear Recollection (mDo dran-pa nyer-bzhag; Saddharmanusmriti-upasthana):

»As the chief among the obstructors (bar-du gcod-pa) of all virtuous qualities is the sinful teacher, one should abandon being associated with him, speaking with him, or even being touched by his shadow.«

In every aspect one should be diligent in rejecting the sinful teacher

Je Tsongkhapa. Lamrim Chen Mo, »The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment«, the page 75-77, Snow Lion Publ. »The defining characteristics of the student who relies upon the teacher«

Aryadeva states in his Four Hundred Stanzas (Catuh-sataka):

»It is said that one who is nonpartisan, intelligent, and diligent Is a vessel for listening to the teachings. The good qualities of the instructor do not appear otherwise Nor do those of fellow listeners.«

Aryadeva says that one who is endowed with the three qualities is suitable to listen to the teachings. He also says that if you have all these qualities, the good qualities of one who instructs you in the teachings will appear as good qualities, not as faults. In addition, he says that to such a fully qualified person the good qualities of fellow listeners will also appear as good qualities and not as faults.

It is stated in Candrakirti’s commentary that if you, the listener, do not have all these defining characteristics of a suitable recipient of the teachings, then the influence of your own faults will cause even an extremely pure teacher who instructs you in the teachings to appear to have faults. Furthermore, you will consider the faults of the one who explains the teachings to be good qualities. Therefore, although you might find a teacher who has all the defining characteristics, it may be difficult to recognize their presence.

Thus, it is necessary for the disciple to have these three characteristics in their entirety in order to recognize that the teacher has all the defining characteristics and in order then to rely on that teacher.

With respect to these three characteristics, »nonpartisan« means not to take sides. If you are partisan, you will be obstructed by your bias and will not recognize good qualities. Because of this, you will not discover the meaning of good teachings. As Bhavaviveka states in his Heart of the Middle Way (Madhyamaka-hrdaya):

Through taking sides the mind is distressed, Whereby you will never know peace

»Taking sides« is to have attachment for your own religious system and hostility toward others’. Look for it in your own mind and then discard it, for it says in the Bodhisattva Vows of Liberation (Bodhi-sattva-pratimoksa):

After giving up your own assertions, respect and abide in the texts of the abbot and master

Question: Is just that one characteristic enough? Reply: Though nonpartisan, if you do not have the mental force to distinguish between correct paths of good explanation and counterfeit paths of false explanation, you are not fit to listen to the teachings. Therefore, you must have the intelligence that understands both of these. By this account you will give up what is unproductive, and then adopt what is productive.

Question: Are just these two enough? Reply: Though having both of these, if, like a drawing of a person who is listening to the teachings, you are inactive, you are not fit to listen to the teachings. Therefore, you must have great diligence. Candrakirti’s commentary says »After adding the three

qualities of the student to the two qualities of being focused and having respect for the teaching and its instructor, there are a total of five qualities.« Then, these five qualities can be reduced to four: (1) striving very diligently at the teaching, (2) focusing the mind well when listening to the teaching, (3) having great respect for the teaching and its instructor, and (4) discarding bad explanations and retaining good explanations.

Having intelligence is the favourable condition that gives rise to these. Being nonpartisan gets rid of the unfavourable condition of taking sides. Investigate whether these attributes that make you suitable to be led by a guru are complete; if they are complete, cultivate delight. If they are incomplete, you must make an effort to obtain the causes that will complete them before your next life. Therefore, know these qualities of a listener. If you do not know their defining characteristics, you will not engage in an investigation to see whether they are complete, and will thereby ruin your great purpose.

Kalama Sutra« by the Buddha:

»It is proper for you, Kalamas, to doubt, to be uncertain; uncertainty has arisen in you about what is doubtful. Come, Kalamas. Do not go upon what has been acquired by repeated hearing; nor upon tradition; nor upon rumor; nor upon what is in a scripture; nor upon surmise; nor upon an axiom; nor upon specious reasoning; nor upon a bias towards a notion that has been pondered over; nor upon another’s seeming ability; nor upon the

consideration, 'The monk is our teacher.' Kalamas, when you yourselves know: 'These things are bad; these things are blamable; these things are censured by the wise; undertaken and observed, these things lead to harm and ill,' abandon them. …«

Buddha in »The Tibetan Dhammapada« – Chapter Intimate Friends

1 Wise ones, do not befriend The faithless, who are mean And slanderous and cause schism. Don’t take bad people as your companions.

2 Wise ones, be intimate With the faithful who speak gently, Are ethical and do much listening. Take the best as companions.

3 Do not devote yourself To bad companions and wicked beings. Devote yourself to holy people, And to spiritual friends.

4 By devotion to people like that You will do goodness, not wrong.

5 By devotion to faithful and wise people Who have heard much and pondered many things, By heeding their fine words, even from afar, Their special qualities are attained here.

6 Since those devoted to inferiors degenerate, Those to equals mark time, And those to great ones attain sanctity, Be devoted to those great ones.

7 By devotion to ethical, Calm, and most knowledgeable great beings, One attains to a greatness Greater even than the great.

8 Just as the clean kusha grass That wraps a rotten fish Will also start to rot, So too will those devoted to an evil person.

9 Just as a leaf folded To contain an incense offering Also becomes sweet, So too will those devoted to the virtuous.

10 When one does no wrong yet Is devoted to evil people, One will still be abused, For others suppose that this one too is bad.

11 The devotee acquires the same faults As the person not worthy of devotion, Like an untainted arrow smeared With the poison of a tainted sheath.

12 Steadfast ones who fear the taint of faults, Do not befriend bad people. By close reliance and devotion To one’s companion, Soon one becomes just like The object of one’s devotion.

13 Therefore, knowing that one’s devotion Is like the casing of the fruit, The wise devote themselves to holy, Not to unholy people,

And drawn along the monk’s path They find the end of misery

14 Just as a spoon cannot taste the sauce, Infantile ones do not understand The doctrine, even after A lifetime of devotion to the wise.

15 Just as the tongue can taste the sauce. Those with wisdom can understand The entire doctrine, after just A brief attendance on the wise.

16 Because infantile ones lack eyes to see, Though they devote their lifetimes To the wise, they never Understand the entire doctrine. Those with wisdom fully understand The entire doctrine after just A brief attendance on the wise. They have eyes to see.

17 Though they devote their lifetimes To wise beings, infantile ones Do not understand the doctrine Of the Buddha in its entirety. Those with wisdom understand The doctrine of the Buddha In its entirety after just A brief attendance on the wise.

18 Even just one meaningful line Sets the wise ones to their task, But all the teaching that the Buddhas gave Won’t set infantile ones to work.

19 The intelligent will understand A hundred lines from one, But for the infantile beings A thousand lines do not suffice for one.

20 [If one must chose between them], Better the wise even if unfriendly. No infant is suited to be a friend. Sentient beings intimate with The infant-like are led to hell.

21 Wise persons are those who know Infantile ones for what they are: 'Infantile ones' are those Who take infants to be the wise.

22 The censure of the wise Is far preferable To the eulogy or praise Of the infant.

23 Devotion to infants brings misery. Since they are like one’s foe, It is best to never see or hear Or have devotion for such people. 24 Like meeting friends, devotion to The steadfast causes happiness.

25 Therefore, like the revolving stars and moon, Devote yourself to the steadfast, moral ones Who have heard much, who draw on what is best The kind, the pure, the best superior ones.

(taken from Gareth Sparham’s translation Wisdom Publications)

In “Healing Anger – The power of patience from a Buddhist perspective” pub. Snow Lion, USA 1997, pp 83–85, H.H. the Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, states:

Q: What do you think about Dharma teachers who speak and write about Dharma beautifully, but do not live it? A: Because Buddha knew of this potential

consequence, he was very strict in prescribing the qualities that are necessary for a person to be qualified as a teacher. Nowadays, it seems, this is a serious issue. First on the teacher’s side: the person who gives some teaching, or gives talks on Dharma must have really trained, learned, and studied.

Then, since the subject is not history or literature, but rather a spiritual one, the teacher must gain some experience. Then when that person talks about a religious subject with some experience, it carries some weight. Otherwise, it is not so effective. Therefore, the person who begins to talk to others

about the Dharma must realize the responsibility, must be prepared. That is very important. Because of this importance, Lama Tsongkhapa, when he describes the qualifications that are necessary for an individual to become a teacher, quotes from Maitreya’s Ornament of Scriptures, in which Maitreya lists most of

the key qualifications that are necessary on the part of the teacher, such as that the teacher must be disciplined, at peace with himself, compassionate, and so on. At the conclusion, Lama Tsongkhapa sums up by stating that those who wish to seek a spiritual teacher must first of all be aware of what the

qualifications are that one should look for in a teacher. Then, with that knowledge, seek a teacher. Similarly, those who wish to seek students and become teachers must not only be aware of these conditions, but also judge themselves to see whether they possess these qualities, and if not, work towards

possessing them. Therefore, from the teachers’ side, they also must realize the great responsibility involved. If some individual, deep down, is really seeking money, then I think it is much better to seek money through other means. So if the deep intention is a different purpose, I think this is very

unfortunate. Such an act is actually giving proof to the Communist accusation that religion is an instrument for exploitation. This is very sad. Buddha himself was aware of this potential for abuse. He therefore categorically stated that one should not live a way of life which is acquired through five wrong

means of livelihood. One of them is being deceptive and flattering toward one’s benefactor in order to get maximal benefit. Now, on the students’ side, they also have responsibility. First, you should not accept the teacher blindly. This is very important. You see, you can learn Dharma from someone you accept

not necessarily as a guru, but rather as a spiritual friend. Consider that person until you know him or her very well, until you gain full confidence and can say, “Now, he or she can be my guru.” Until that confidence

develops, treat that person as a spiritual friend. Then study and learn from him or her. You also can learn through books, and as time goes by, there are more books available. So I think this is better. Here I would like to mention a point which I raised as early as thirty years ago about a particular aspect

of the guru-disciple relationship. As we have seen with Shantideva’s text Guide to the Bodhisatva’s Way of Life, we find that in a particular context certain lines of thought are very much emphasized, and unless you see the argument in its proper context there is a great potential for misunderstanding.

Similarly, in the guru-disciple relationship, because your guru plays such an important role in serving as the source of inspiration, blessing, transmission, and so on, tremendous emphasis is placed on maintaining proper reliance upon and a proper relationship with one’s guru. In the texts

describing these practices we find a particular expression, which is, “May I be able to develop respect for the guru, devotion to the guru, which would allow me to see his or her every action as pure.” I stated as early as thirty years ago that this is a dangerous concept. There is a tremendous potential

for abuse in this idea of trying to see all the behaviours of the guru as pure, of seeing everything the guru does as enlightened. I have stated that this is like a poison. To some Tibetans, that sentence may seem a little bit extreme. However, it seems now, as time goes by, that my warning has become

something quite relevant. Anyway, that is my own conviction and attitude, but I base the observation that this is a potentially poisonous idea on Buddha’s own words. For instance, in the Vinaya teachings, which are the scriptures that outline Buddha’s ethics and monastic discipline, where a relationship

toward one’s guru is very important, Buddha states that although you will have to accord respect to your guru, if the guru happens to give you instructions which contradict the Dharma, then you must reject them. There are also very explicit statements in the sutras, in which Buddha states that any instructions

given by the guru that accord with the general Dharma path should be followed, and any instructions given by the guru that do not accord with the general approach of the Dharma should be discarded. It is in the practice of Highest Yoga Tantra of Vajrayana Buddhism where the gurudisciple relationship assumes

great importance. For instance, in Highest Yoga Tantra we have practices like guru yoga, a whole yoga dedicated toward one’s relation to the guru. However, even in Highest Yoga Tantra we find statements which tell us that any instructions given by the guru which do not accord with Dharma cannot be followed. You

should explain to the guru the reasons why you can’t comply with them, but you should not follow the instructions just because the guru said so. What we find here is that we are not instructed to say, “Okay, whatever you say, I will do it,” but rather we are instructed to use our intelligence and judgment and reject instructions which are not in accord with Dharma.

However we do find, if we read the history of Buddhism, that there were examples of single-pointed guru devotion by masters such as Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, and Milarepa which may seem a little extreme. But we find that while these masters, on the surface, may look like outcasts or beggars, or they may have

strange behaviours which sometimes lead other people to lose faith, nevertheless when the necessity came for them to reinforce other people’s faith in the Dharma and in themselves as spiritual teachers, these masters had a counterbalancing factor – a very high level of spiritual realization. This was so much

so that they could display supernatural powers to outweigh whatever excesses people may have found in them, conventionally speaking. However, in the case of some of the modern-day teachers, they have all the excesses in their unethical behaviours but are lacking in this counterbalancing factor, which is the

capacity to display supernatural powers. Because of this, it can lead to a lot of problems. Therefore, as students, you should first watch and investigate thoroughly. Do not consider someone as a teacher or guru until you have certain confidence in the person’s integrity. This is very important. Then, second, even after that, if some unhealthy things happen, you have the liberty to reject them. Students should make sure that they don’t spoil the guru. This is very important.

In “The Gelug/Kagyu Tradition of Mahamudra”, pp. 209–211, His Holiness the Dalai Lama states: Premature Commitment To An Unsuitable Guru

In some cases it happens that disciples do not examine a spiritual teacher very carefully before accepting him or her as their guru and committing

themselves to a guru/disciple relationship. They may even have received tantric empowerments from this teacher. But then they find they were wrong. They see many flaws in this teacher and discover many serious mistakes he or she has made. They find that this teacher does not really suit them. Their minds are uneasy regarding this person and they are filled with doubts and possibly regret. What to do in such a circumstance? The mistake, of course, is that

originally the disciples did not examine this teacher very carefully before committing themselves to him or her. But this is something of the past that has already happened. No one can change that. In the future, of course, they must examine any potential guru much more thoroughly. But, as for what to do now in this particular situation with this particular guru, it is not productive or helpful to continue investigating and scrutinizing him or her in terms of suspicions or doubts. Rather, as The Kalachakra Tantra recommends, it is best to keep a

respectful distance. They should just forget about him or her and not have anything further to do with this person. It is not healthy, of course, for disciples to deny serious ethical flaws in their guru, if they are in fact true, or his or her involvement in Buddhist power-politics, if this is the case.

To do so would be a total loss of discriminating awareness. But for disciples to dwell on these points with disrespect, self-recrimination, regret or other negative attitudes is not only unnecessary, unhelpful and unproductive, it is also improper. They distance themselves even further from achieving a peaceful state of mind and may seriously jeopardize their future spiritual progress. I think it best in this circumstance just to forget about this

teacher. Premature Commitment To Tantra And Daily Recitation Practices It may also occur that disciples have taken tantric empowerments prematurely, thinking that since tantra is famous as being so high, it must be beneficial to take this initiation. They feel they are ready for this step and take the empowerment, thereby committing themselves to the master conferring it as now

being their tantric guru. Moreover, they commit themselves as well to various sets of vows and a daily recitation meditation practice. Then later these disciples realize that this style of practice does not suit them at all, and again they are filled with doubts, regrets, and possibly fear. Again, what to do? We can understand this with an analogy. Suppose, for instance, we go to a store, see some useful but exotic item that strikes our fancy and just buy it

on impulse, even though it is costly. When we bring it home, we find, after examining the item more soberly now that we are out of the exciting, seductive atmosphere of the marketplace, that we have no particular use for it at the moment. In such situation, it is best not to throw the thing out in the garbage, but rather to put it aside. Later we might find it, in fact, very useful. The same conclusion applies to the commitments disciples have taken

prematurely at a tantric empowerment without sufficient examination to determine if they were ready for them. In such situations, rather than deciding that they are never going to use it at all and throwing the whole thing away, such disciples would do better to establish a neutral attitude toward it, putting tantra and their commitments aside and leaving it like that. This is because they may come back to them later and find them very precious and useful.

Suppose, however, disciples have taken an empowerment and have accepted the commitment to practice the meditations of a particular Buddha-form by reciting a sadhana, a method of actualization, to guide them through a complex sequence of visualization and mantra repetition. Although they still have faith in tantra, they find that their recitation commitment is too long and it has become a great burden and strain to maintain it as a daily practice. What to do then? Such disciples should

abbreviate their practice. This is very different from the previous case in which certain disciples find that tantric practice in general does not suit them at the present stage of their spiritual life. Everyone has time each day to eat and to sleep. Likewise, no matter how busy they are, no matter how many family and business responsibilities they may have, such disciples can at least find a few minutes to maintain the daily continuity of generating themselves in their imagination in the aspect of a Buddha-form and reciting the appropriate mantra. They must make some effort. Disciples can never progress anywhere on the spiritual path if they do not make at least a minimal amount of effort.

In “The Gelug/Kagyu Tradition of Mahamudra”, pp. 185–186, His Holiness the Dalai Lama states about The Root Guru

Sometimes we differentiate a root guru from our other gurus and focus particularly on him or her for our practice of guru-yoga. Our root guru is usually described in the context of tantra as the one who is kind to us in three ways. There are several manners of explaining these three types of kindness. One, for example, is the kindness to confer upon us empowerments, explanatory discourses on the tantric practices and special guideline instructions for them. If we have received empowerments and discourses from many gurus, we consider as our root guru the one who has had the most beneficial effect upon us. For deciding this, we do not examine in terms of the actual qualifications of the guru from his or her own side, but rather in terms of our own side and the benefit we have gained in our personal development and the state of mind this guru elicits in us. We consider the rest of our gurus as emanations or manifestations of that root guru …

Further Sources

It is advised in the Kalachakra Tantra, that one can leave a teacher – one goes to a neutral distance – if one sees to many obvious faults. The way of disconnecting to such teachers is taught in: ‣»The Teacher-Student Relationship« by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodu Thaye and in his book »Buddhist Ethics«. ‣There is also an online commentary »Unhealthy Relationships with Spiritual Teachers« available by Alex Berzin, a close disciple of Tsenshab Serkong Rinpoche. In the latter text please read the following sections carefully: Chapter 15 Fear of »A Breach of Guru-Devotion« http://www.berzinarchives.com/e-books/spir...teacher_15.html

Maybe it is also a good idea to start with rectifying Buddhist terms … ‣Rectification of the term »Spiritual Guide«, »Guru« … http://www.berzinarchives.com/e-books/spir..._teacher_2.html ‣and Rectifying the Term »Devotion« http://www.berzinarchives.com/e-books/spir..._teacher_9.html

Than you can read the text of Tsongkhapa »Fruit Clusters of Siddhis« in »Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice« and you will see it will be very hard to go to hell by leaving a Guru, because to go to hell you need a lot of negative attitudes and must be in a way in long-time-hate-delusions. Which will surely not be the case for the most human beings. Just leaving a Guru and going to neutral distance is no negative action, this is rather advised in special cases. Online Links

About the Teacher-Student-Relationship ‣Ethics in the Teacher-Student Relationship: The Responsibilities of Teachers and Students by H.H. the XIV. Dalai Lama ‣Questioning the Advice of the Guru by H.H. the XIV. Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso ‣Relating to the Guru by Jetsünma Tenzin Palmo ‣Devotion with Discernment – A question of personal responsibility by Rob Preece ‣The Teacher-Student-Relationship by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye ‣Relating to a Spiritual Teacher: Building a Healthy Relationship by Dr. Alexander Berzin ‣East-West, West-East by Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche ‣Approaching the Guru by Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche

Spiritual Teacher and Sexual Abuse / Sexual Exploitation ‣Sex and the Spiritual Teacher by Scott Edelstein ‣Books On Sexual Exploitation By Professionals - Selected and reviewed by James Park ‣Use Common Sense: Khandro Rinpoche about Sexual Abuse by Buddhist Teachers in the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition ‣Sex in the Sangha … Again – Tricycle: Four teachers discuss the systemic issues that have led to sexual abuse in Buddhist communities

More ‣Open Letter - Conference of Western Buddhist Teachers

About Sectarianism

Here is an abstract from Ven Ringu Tulku’s book about the Rime Philosophy: Jamgon Kongtrul on Sectarianism

Jamgon Kongtrul disagreed so thoroughly with a partisan approach that he asserted that those with sectarian views cannot uphold even their own tradition. Kongtrul says:

»Just as a king overpowered by self-interest Is not worthy of being the protector of the kingdom, A sectarian person is not worthy of being a holder of the dharma. Not only that, he is unworthy of upholding even his own tradition.«

And again:

»The noble ones share a single ultimate view, But arrogant ones bend that to their own interests. Those who show all the teachings of the Buddha as without contradiction can be considered learned people. But who would be foolish enough to think that those who cause discord are holders of the dharma?

Ri-me is not a way of uniting different schools and lineages by emphasizing their similarities. It is basically an appreciation of their differences and an

acknowledgment of the importance of variety to benefit practitioners with different needs. Therefore, the Ri-me teachers always take great care that the

teachings and practices of the different schools and lineages, and their unique styles, do not become confused with one another. Retaining the original style and methods of each teaching lineage preserves the power of that lineage experience. Kongtrul and Khyentse made great efforts to retain the original

flavor of each teaching, while making them available to many. Kongtrul writes about Khyentse in his biography of the latter: »Some people are very fussy about the refutations and affirmations of the various tenets, becoming particularly attached to their own versions, such as

Rangtong or Shentong Madhyamaka. There are many who try to pull others over to their own side, to the point of practically breaking their necks. When Jamyang Khyentse teaches the different tenet systems, he does not mix up their terminology or ideas, yet he makes them easy to understand and suitable for

the students. In general, the main point to be established by all the tenets is the ultimate nature of phenomena. As the Prajnaparamita Sutra states:

'The dharmata is not an object of knowledge; It cannot be understood by the conceptual mind.'

In addition, Ngok Lotsawa, who is considered the crown jewel of Tibetan intellectuals, agrees with this understanding when he says:

'The ultimate truth is not only beyond the dimension of language and expression, it is beyond intellectual understanding.'

So, the ultimate nature cannot be established by the samsaric mind, no matter how deep that mind may be.

The scholars and siddhas of the various schools make their own individual presentations of the dharma. Each one is full of strong points and supported by valid reasoning. If you are well grounded in the presentations of your own tradition, then it is unnecessary to be sectarian. But if you get mixed up about

the various tenets and the terminology, then you lack even a foothold in your own tradition. You try to use someone else’s system to support your

understanding, and then get all tangled up, like a bad weaver, concerning the view, meditation, conduct, and result. Unless you have certainty in your own system, you cannot use reasoning to support your scriptures, and you cannot challenge the assertions of others. You become a laughing stock in the eyes of the learned ones. It would be much better to possess a clear understanding of your own tradition.

In summary, one must see all the teachings as without contradiction, and consider all the scriptures as instructions. This will cause the root of sectarianism and prejudice to dry up, and give you a firm foundation in the Buddhas teachings. At that point, hundreds of doors to the eighty-four thousand teachings of the dharma will simultaneously be open to you.«

The Ri-me concept was not original to Kongtrul and Khyentse, nor was it new to Buddhism. Shakyamuni Buddha forbade his students to criticize others, even the teachings and teachers of other religions and Cultures. This directive was so strong and unambiguous that in the Introduction to the Middle Way, Chandrakirti felt compelled to defend Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka treatises by saying:

»If, in trying to understand the truth, one dispels misunderstandings, and therefore some philosophies cannot remain intact, that should not be considered as criticizing others’ views.«