TIBETAN BUDDHIST MEDITATION.

Tibetan meditation is called “lhagthong.” The term "lhag" means "higher", "superior", "greater"; the term "thong" is "view" or "to see", hence together, lhagthong is taken to mean "superior seeing", "great vision" or "supreme wisdom." This may be interpreted as a "superior manner of seeing", and also as "seeing that which is the essential nature". Its nature is a lucidity — a clarity of mind. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Dalai Lama said, "The very purpose of meditation is to disciple the mind and reduce afflictive emotions." Some nuns meditate while pouring seeds into a plate, brushing them off and collecting them and then repeating the process over and over again.

Advanced Tibetan Buddhist monks are trained to remember complex images as a way to clear their minds and achieve new levels of awareness. According to an article published in the Washington Post, “An experienced monk can visualize the details of as many as 700 deities used in meditation. Sometimes they would visualize the deity close up, sometimes from far away...some experienced meditators can keep a mental image in their minds for minutes and even days." Some psychologists say this is impossible. Their research shows that subjects can only mental images for seconds.

When asked about the techniques to rid oneself of desire and attachment, a Tibetan monk said, “The lamas taught us to stare at a statue of the Lord Buddha and absorb the details of the object the color, the posture, and so on, reflecting back all we knew of their teachings. Slowly you go deeper; you visualize the hand, the leg, and thevajra in his hand, closing your eyes and trying to travel inward. The more you concentrate on a deity, the more you are diverted from worldly thoughts.

Some Bhutanese monks have reportedly mastered a form of meditation known as "lunggom"---meaning "walking on air"---which allows the monks to project themselves and travel around the countryside without leaving the monastery. One monk told a National Geographic writer who asked him demonstrate, "Unfortunately, it takes much time to learn the theoretical aspects of lunggom before one can put it into practice so I'm afraid that we will just have to walk normally."

Websites and Resources: Yoga National Institutes of Health, US government, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Yoga: Its Origin, History and Development, Indian government mea.gov.in/in-focus-article ; Different Types of Yoga - Yoga Journal yogajournal.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga Wikipedia ; Medical News Today medicalnewstoday.com ; Yoga and modern philosophy, Mircea Eliade crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ; India's 10 most renowned yoga gurus rediff.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga philosophy Wikipedia ; Yoga Poses Handbook mymission.lamission.edu ; George Feuerstein, Yoga and Meditation (Dhyana) santosha.com/moksha/meditation

Tibetan Buddhism and Tantrism

Tantrism is an important element of Tibetan Buddhism, which grew out of Mahayana Buddhism but is sometimes regarded as one of the three major sects of Buddhism along with Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism. Originally from India, Tantrism it is a highly ritualistic form of religion expression that combines beliefs in magic and esoteric philosophy and emphasizes mystic symbols, sacred chants, and other esoteric devotional techniques. It is associated Hinduism as well as Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism is called Vajrayana ("thunderbolt vehicle"). In Tibet, it is heavily influenced by the ancient Bon religion, which used shaman to dispel demons and appease the gods, and incorporates a number of mudras ("ritual postures"), mantras ("sacred speech"), yantras ("sacred art") and secret initiation rites. Most of the ritual objects and images of deities used in Tibetan Buddhism are derived from Tantrism. The techniques are generally not written down but passed orally from master to student.

Tantrism emerged around A.D. 600 and was based on texts known as Tantras. It put forth the idea that all human states and conditions, even one traditionally regarded as polluting," were connected and things such as desire and wrath could be viewed as being on the same plane with love and righteousness.

Tantrism is seen by some as a complex union of Hinduism and Buddhism: incorporating different offshoots of each religion with folk religious beliefs and combing Hindu gods with Buddhist theology. One religious text described Tantrism as “Buddhist and Hindu hierarchies converted to create rigid social organizational patterns” that merge “erotic Hindu ideas...static and authoritative Buddhist teachings...Hindu patterns of individual paths to enlightenment” and “Buddhist notions of the power of many."

Tantric Techniques

Tantric Buddhists believe that anyone willing to pursue a regimen of ritual-intensive discipline can reach enlightenment now, and in the process benefit all other creatures, which is the ultimate goal. To achieve enlightenment special tools are needed. These include items that can be touched, held or worn . These tools are not intended to be art works that are mediated upon. Rather they are seen as objects that contact turns into a two-way power sources, with devotees injecting the objects with power and that objects returning the power with an extra punch to the devotee. The power exchange goes back and forth in a way that is referred to as the “Circle of Bliss."

According to followers of Buddhist Tantrism the Buddha left behind some special esoteric techniques, known as Tantra (Gyu), to a small group of his disciples with the understanding that if these techniques were followed they could achieve nirvana (enlightenment) and become a bodhisattvas much more quickly than if they followed conventional methods.The techniques often involve identification with a tutelary deity through deep meditation and recitation of deity's mantra, the most well-known of which is “om mani padem hum," the mantra of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara). The process is enhanced by the use of yogic techniques that may include sexual acts. Masters of Tantric methods can not only visualize a deity in all its forms but can visualize it in a three'dimensional mandala world and absorb its terma (“reveled” words or writings).

Tantric objects include bells to wake up slumbering minds, prayer wheels and mandalas. New York Times Art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “the function and meaning of mandalas and other their such objects can be fully explained only in an interpretive calculus of prodigious complexity, one ultimately accessible only to initiates."

Tibetan Meditation Techniques

Tibetan Buddhism includes all of the traditional forms of Mahayana meditation and also several unique forms. The central defining form is Deity Yoga (devatayoga). This involves the recitation of mantras, prayers and visualization of the yidam or deity along with the associated mandala of the deity's Pure Land. Advanced Deity Yoga involves imagining yourself as the deity. Other forms of Tibetan Buddhist meditation include the Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings, taught by the Kagyu and Nyingma schools respectively. The goal of these is to familiarize oneself with the ultimate nature of mind which underlies all existence, the Dharmakaya. There are also other practices such as Dream Yoga, Tummo, the yoga of the intermediate state (at death) or Bardo, sexual yoga and Chöd. The shared preliminary practices of Tibetan Buddhism are called ngöndro, which involves visualization, mantra recitation, and many prostrations. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the China Buddhism Encyclopedia: Deity yoga is “a sadhana in which practitioners visualize themselves as a deity or yidam. Deity Yoga brings the meditator to the experience of being one with the deity. Deity Yoga employs highly refined techniques of creative imagination, visualization, and photism in order to self-identify with the divine form and qualities of a particular deity as the union of method or skilful means and wisdom. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, "In brief, the body of a Buddha is attained through meditating on it"

“By visualizing oneself and one's environment entirely as a projection of mind, it helps the practitioner to become familiar with the mind's ability and habit of projecting conceptual layers over all experience. This experience undermines a habitual belief that views of reality and self are solid and fixed. Deity yoga enables the practitioner to release, or 'purify' him or herself from spiritual obscurations (Sanskrit: klesha) and to practice compassion and wisdom simultaneously. Recent studies indicate that Deity yoga yields quantifiable improvements in the practitioner's ability to process visuospatial information, specifically those involved in working visuospatial memory.”

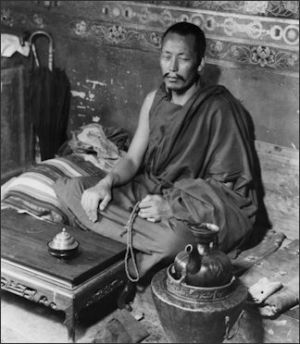

Contemporary Tibetan scholar Thrangu Rinpoche wrote: “In general there are two kinds of meditation: the meditation of the pandita who is a scholar and the nonanalytical meditation or direct meditation of the kusulu, or simple yogi. . . the analytical meditation of the pandita occurs when somebody examines and analyzes something thoroughly until a very clear understanding of it is developed. . . The direct, nonanalytical meditation is called kusulu meditation in Sanskrit. This was translated as trömeh in Tibetan, which means "without complication" or being very simple without the analysis and learning of a great scholar. Instead, the mind is relaxed and without applying analysis so it just rests in its nature. In the su-tra tradition, there are some nonanalytic meditations, but mostly this tradition uses analytic meditation.

Tibetan Buddhist Prayers, Chants and Sutras

The Tibetan worship gesture, involves clasping the hands in the prayer position and touching the hands to the head, mouth and heart. Pilgrims at sacred sites often do this and then raise their hands to the sky and prostrate themselves on the ground.

Morning prayers at monasteries begin with the lighting of endless rows of yak-butter candles, chants and blasts from long horns. Common mantras are those for Guru Rinpoche (“om ah hum vajra guru padma siddhi hung”) and Jampelyang (“om ahra paza nu dhi dhi").

The most common chant is om mani padme hum ("Hail to the Jewel in the Lotus"), which means "I invoke this path to experience the universality, so the jewel-like luminosity of my immortal mind will be unfolded within the depths of the lotus-center of awakened consciousness and I be wafted by ecstasy of breaking through all bonds and horizons." It is the mantra of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara), the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Thrangu Rinpoche wrote: “The approach in the sutras . . .is to develop a conceptual understanding of emptiness and gradually refine that understanding through meditation, which eventually produces a direct experience of emptiness . . . we are proceeding from a conceptual understanding produced by analysis and logical inference into a direct experience . . . this takes a great deal of time. . . we are essentially taking inferential reasoning as our method or as the path. There is an alternative . . . which the Buddha taught in the tantras . . . the primary difference between the sutra approach and the approach of Vajrayana (secret mantra or tantra) is that in the sutra approach, we take inferential reasoning as our path and in the Vajrayana approach, we take direct experience as our path. In the Vajrayana we are cultivating simple, direct experience or "looking." We do this primarily by simply looking directly at our own mind.”

Inductive Reasoning and Insight in Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism promotes the idea that mindfulness of breathing becomes a basis for inductive reasoning on such topics as the five aggregates; as a result of such inductive reasoning, the meditator progresses through the Hearer paths of preparation, seeing, and meditation. One scholar describes his approach thus: "the overall picture... is that of a kind of serial alternation between observation and analysis that takes place entirely within the sphere of meditative concentration". [Source: Wikipedia +]

Scholar Klaus-Dieter Mathes of the University of Vienna said that ordinary meditation in the Indo-Tibetan sutrayana tradition “requires an analytical or intellectual assessment of emptiness which is mainly based on” later schools of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy. Bkra shis rnam rgyal, for example, starts the presentation of meditation with the following pith-instructions: “Assume the same body posture as before (i.e., as in samatha practice) and gaze straight [ahead] without blinking or shifting. With lucid and non-conceptual s'amatha as a basis, one should keep one's attention vividly present. In this state look nakedly (rjen lhang gis) into the mind itself to see what shape, colour etc. it has." +

Insight (lhagthong) in Tibetan Buddhist meditation is extremely important because it can eradicate the mental afflications, whereas tranquility [[[shamatha]]] alone cannot. That is why we want to be able to practice tranquility and insight in a unified manner. This unified practice has three steps; first, we practice tranquility; then we practice insight; and then we bring the two together. Doing this will eradicate the cause of samsara (which is mental afflictions), thereby eradicating the result of samsara (which is suffering). For this reason, it is improper to become too attached to the delight or pleasure of tranquility, because tranquility alone is not enough. As was said by Lord Milarepa in a song: "Not being attached to the pool of tranquility." May I generate the flower of insight."

Maha-mudra- and Dzogchen Meditation in Tibetan Buddhism

Meditation is widely used in Maha-mudra and Dzogchen — two prominent Tibetan Buddhist teaching schools. They employ methods of the others traditions but also incorporates different approaches. As is true with Mahayana traditions they include meditating on symbolic images as contemplations but place a greater emphasis on this form of meditation. Additionally, in a way that is consistent with tantrism, the true nature of mind is pointed out by the guru and the practitioner practices with that direct experience as a form of meditation. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Thrangu Rinpoche describes the approach using a guru: “In the Sutra path one proceeds by examining and analyzing phenomena, using reasoning. One recognizes that all phenomena lack any true existence and that all appearances are merely interdependently related and are without any inherent nature. They are empty yet apparent, apparent yet empty. The path of Mahamudra is different in that one proceeds using the instructions concerning the nature of mind that are given by one's guru. This is called taking direct perception or direct experiences as the path. The fruition of s'amatha is purity of mind, a mind undisturbed by false conception or emotional afflictions. The fruition of vipas'yana- is knowledge (prajna-) and pure wisdom (jña-na). Jña-na is called the wisdom of nature of phenomena and it comes about through the realization of the true nature of phenomena.” +

Regarding Thrangu Rinpoche,Mathes states "it should be noted that he generally considers such maha-mudra- teachings, or rather the path of direct cognition, to be Vajraya-na. In other words, he does not claim that they constitute a third path beyond the Sutras and Tantras." “Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche clearly charts the developmental relationship of the practice of samatha and vipasyana [[[Theravada]] Buddhist meditation]: The ways these two aspects of meditation are practiced is that one begins with the practice of shamatha; on the basis of that, it becomes possible to practice vipashyana or lhagthong. Through one's practrice of vipashyana being based on and carried on in the midst of shamatha, one eventually ends up practicing a unification of shamatha and vipashyana. The unification leads to a very clear and direct experience of the nature of all things. This brings one very close to what is called the absolute truth.” This approach appears in some respects reminiscent of the one outlined by the Buddha in early suttas (as opposed to that of later Theravada thought).

Tibetan Buddhist Meditation Caves

Some Tibetan monks and nuns live in caves, some of them set into 500-foot-high cliffs. They often stay there with little more than butter lamps, religious relics, basic food and dried juniper branches.. It is not unusual for monks and nuns to spend several years in solitary retreat. One monk told National Geographic, "Four months ago I came here. There are other monks and nuns around us in solitary meditation. I will soon mediate for three years, three months, and three days."

Describing a meditation cave, Jere Van Dyk wrote in National Geographic, "We saw statues of Buddha and pictures of the Dalai Lama. A man chanted softly. He wore a thick maroon coat and had close cut hair." The people who meditate generally eat very little. Some ascetics it is said subsist on something called Essence Extraction, a spoonful of finely ground rock boiled in water, consumed twice a day.

One monk who meditated in a cave through much of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, emerged in the late 1990s when he reached the level of spiritual growth he had been seeking. Chinese became fascinated with his story and appeared in droves to listen to his lectures.

Rongbuk monastery near the base of the north side of Mount Everest is regarded as the highest monastery in the world, at 4,980 metres (16,340 ft). It was was founded in 1902 by the Nyingmapa Lama Ngawang Tenzin Norbu in an area of meditation huts and caves that had been in use by communities of nuns since the 18th century. Meditation caves dot the cliff walls all around the monastery complex and up and down the valley.

12 Years in a Himalayan Cave

Buddhist nun Tenzin Palmo, a former London librarian, spent several years in a Himalayan cave in India. She told Lucy Powell of The Guardian, “Eventually my guru, Khamtrul Rinpoche, told me to go and practise in the mountain region of Lahaul. It was a lovely monastery, but it wasn't always quiet. I'd heard about a nearby cave and wanted to go there, but local people said it wasn't safe. "Men from the army camp will come and rape you," they warned. "By the time they get up here, they'd be too exhausted," I said. "I'll invite them in for tea." They said there were ghosts, that I'd freeze to death. But I explained the situation to my guru, who said that if the cave faced south and was fairly dry it would be fine. From that point on, I didn't worry. After all, for centuries, hundreds of thousands of hermits have done exactly the same. [Source: by Lucy Powell, The Guardian, 15 May 2009 ^^^]

“I moved into the cave when I was 33 and was very happy. In most places in the world it would be impossible to feel so safe and confident in isolation. We built up a wall to insulate it in winter, and I had an altar and a store room for food. It was simple but pukka. I grew potatoes and turnips in the little garden outside. The day was very structured: four times a day I would sit and meditate in a traditional meditation box for three hours, and that's where I slept, sitting up.

“At first I'd go down to the monastery to listen to teachings, get food supplies, visit my guru and discuss how I was getting on. I'd spend the summers preparing for the long winters when I was completely cut off. But after nine years, I was ready to do a long retreat - three years in complete solitude. Once we had a huge blizzard that raged for seven days and nights, the snow covered the door and window and the whole cave was in complete blackness. I thought: "This is it." Looking back, I'm amazed I wasn't claustrophobic. I felt perfectly calm and resigned. Then I heard a voice say, "Shovel out." I used a saucepan lid and dug a tunnel out. It took an hour or two and I did it three times but survived to tell the tale. ^^^

“The Tibetans have a saying: "If you're sick you're sick; if you die you die." We're all going to die and where better to die than in retreat? Most people worry too much even when things haven't happened; they get all worked up over scenarios of what might happen. The retreat helped me to develop inner resourcefulness and confidence: you learn that you generally do cope with whatever happens. ^^^

“After three years, I heard somebody scrambling over my gate. I hadn't seen anyone all year. When I opened the door a policeman was standing there. He handed me a notice: "You've been in the country illegally for three years. Come down within 24 hours or we'll take action." That was the end of my retreat. It was a bit of a shock.” ^^^

Tummo: Meditation That Raises Body Temperature

Tummo is a form of breathing and meditation used in Tibetan Buddhism that purportedly raises the body temperature of the practitioner by gaining control over body processes during the completion stage of 'highest yoga tantra'. Tummo, some say, refers to “Inner Heat” or “Psychic Heat”.

Miranda Shaw wrote: some forms of yoga and Tibetan meditation offer “a range of techniques to harness the powerful psycho-physical energy coursing through the body... Most people simply allow the energy to churn in a cauldron of chaotic thoughts and emotions or dissipate the energy in a superficial pursuit of pleasure, but a yogi or yogini consciously accumulates and then directs it for specified purposes. This energy generates warmth as it accumulates and becomes an inner fire or inner heat (canda-li-) that [potentially] burns away the dross of ignorance and ego-clinging.”

Peter Malinowski wrote in his blog Meditation Research:The Tummo (also “g-Tummo”) meditation practice is an advanced form of meditation that has been transmitted in the Vajrayana (or Diamond Way) traditions of Tibetan Buddhism for the last 900 years. The spectacular outer sign of this meditation is that adepts are able to significantly raise their body temperature to an extent that they can melt the snow around them or dry wet blankets thrown over their naked body – at least this is how the traditional stories go. [Source: Peter Malinowski, Meditation Research, July 19, 2013, meditation-research.org /*/]

“Generally, Tummo meditation consists of a mental component, where certain images are called to mind, and a bodily, somatic component, where specific breathing practices, body postures and physical body movements are combined. Furthermore, these breathing practices can either be forceful or gentle. /*/

“In the early 1980s researchers from the Harvard Medical School set out to investigate these claims. Visiting three tummo practitioners in the foothills of the Himalayas, the researchers captured increases of peripheral body temperature (at fingers and toes) during this meditation by as much as 8.3 degree Celsius, apparently confirming the claims. However, later on criticism was raised concerning these results, for instance that the temperature range (22 – 33deg C) was in the normal body temperature range. Furthermore, similar increases have been observed merely as a result of changes to respiration and/or muscle contraction and, in consequence, cannot unequivocally be interpreted as a result of the meditation practice per se.” /*/

Research on Tummo Meditation

In 2013, researchers studying ten meditators of Tibetan Buddhism, provided form evidence that tummo was indeed something that was measurable and seemed to be real. Malinowski wrote: An international team of researchers from the US, Singapore and Germany again ventured to the Himalayas to take a fresh and more detailed look at the issue. This time 10 meditators (7 female) from the Nyingma and Kagyu meditation traditions of Tibetan Buddhism took part in the study. By considering two important aspects of this meditation practice, they were able to advance the understanding of this curious effect. To shed light on what is taking place during this type of meditation, the scientists aimed to distinguishing between these different components. The meditators were asked to go through a sequence of four meditation conditions: 1) forceful breathing exercises without the mental component, 2) gentle breathing exercises without the mental component, 3) forceful breathing exercises combined with the mental meditation component and 4) gentle breathing exercises combined with the mental meditation component. At the same time the scientists recorded the electrical brain activity using electroencephalography (EEG) and the peripheral body temperature (at the fifth finger) and core body temperature (in the armpit).”

“The study confirmed that the meditators were able to increase their core body temperature (in the armpit) significantly. Also increases of the peripheral temperature at the fingers was observed, but the authors argue that these may merely result from changes in the position of the hand during the practice rather be caused by meditation or breathing techniques. Interestingly, the increase in core body temperature only happened during the forceful breathing periods (with and without meditation), not during gentle breathing. During the latter periods the meditators maintained the increased temperature, though. This observation seems to confirm the explanation provided by the meditators that forceful breathing meditation is used to increase the body temperature, whereas gentle breathing meditation is used to maintain it. /*/

“But as there was an increase in core body temperature resulting from the forceful breathing with and without meditation, what's the purpose of the meditation, of calling certain images to mind? Well, the data also show that the core temperature reached the slightly feverish range (of up to 38.5 C) only when forceful breathing was combined with meditation, whereas during forceful breathing alone temperatures, although elevated, remained in the range of normal body temperature.

“The scientists also measured the electrical brain activity with EEG. The most prominent finding here was that one particular brain rhythm, the so-called alpha rhythm (oscillating in the range of 8.5–12.5 Hz), increased in power during forceful breathing. Interestingly, the greater the increase in alpha power achieved during tummo meditation was, the longer the core temperature rose, and the higher the achieved temperature was. New evidence from cognitive neuroscience indicates that this alpha rhythm might reflect that the brain is decreasing the distractibility of ‘‘external’’ sensory events to aid concentration on the internal mental activity. The results thus seem to indicate that the quality of the meditation during forceful breathing, as reflected by increased alpha power, seems to determine for how long the meditators are capable of continuing to raise their body temperature beyond the normal range without reaching an equilibrium phase.”

Tibetan Buddhist Art as Meditation Aids

In Tibetan art the emphasis is placed on the "sacred process" and devotional aspects of the work rather than the aesthetic qualities and originality of the finished product as is often the case with Western art. Tibetan art is expected to be a tool for enlightenment rather an expression of the self. John Listopadm an expert on Tibetan art told the Los Angeles Times, "Tibetan art is psychological art and meditational. It is an art which works on people and their personalities. It can calm you down and help you find peace and balance."

Kathryn Selig Brown wrote in the Metropolitan Museum of Art website: “Many sculptures and paintings were made as aids for Buddhist meditation. The physical image became a base to support or encourage the presence of the divinity portrayed in the mind of the worshipper. Images were also commissioned for any number of reasons, including celebrating a birth, commemorating a death, and encouraging wealth, good health, or longevity. Buddhists believe that commissioning an image brings merit for the donor as well as to all conscious beings. Images in temples and in household shrines also remind lay people that they too can achieve enlightenment." [Source: Kathryn Selig Brown, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art]

When asked about the techniques to rid oneself of desire and attachment, a Tibetan monk said, “The lamas taught us to stare at a statue of the Lord Buddha and absorb the details of the object the color, the posture, and so on, reflecting back all we knew of their teachings. Slowly you go deeper; you visualize the hand, the leg, and thevajra in his hand, closing your eyes and trying to travel inward. The more you concentrate on a deity, the more you are diverted from worldly thoughts. It is difficult, of course, but it is also essential. In the Fire Sermon, the Lord Buddha said, The world is on fire and every solution short of nirvana is like trying to whitewash a burning house. Everything we have now is like a dream impermanent. This floor feels like stone, this cupboard feels like wood but really it is an illusion. When you die you can't take any of this. You have to leave it all behind. We have to leave even this human body."

Many works of Tibetan Buddhist art are connected with Tantric rituals and are regarded as tools for meditation and worship. Some art objects can he touched, owned, held and moved. Others are meant to be meditated on. These incorporate a “Circle of Bliss," a sharing of power between the observer and the work of art.

Mandalas

A mandala is a form of Buddhist prayer and art that is usually associated with a particular Buddha and his ascension to enlightenment. Regarded as a powerful center of psychic energy, it symbolizes the macrocosm of the universe, the miniature universe of the practitioner and the platform on which the Buddha addresses his followers. The design for the mandala is said to have been brought to Tibet by the legendary 1,000-year-old lama, Guru Rinpoche, in the Each Ox Year of 749.

A typical mandala measures five feet across and contains a pictorial diagram of Buddhist deities in circular concentric geometric shapes. Many are shaped like a lotus flower with a round center and eight pedals, with a central deity surrounded by four to eight other deities who are manifestations of the central figure. The deities are often accompanied by consorts. In large mandalas there may several dozen circles of deities, with hundreds of deities.

Mandalas can be painted, constructed of stone, embroidered, sculptured or even serve as the layout plan for entire monasteries.. Most are painstakingly made from sand, preferably sand made from millions of grains of crushed, vegetable-dyed marble. The tradition of making mandalas is said to be derived from ancient folk religions and Hinduism. Today mandalas are mostly made by followers of Tantric Buddhism.

Most mandalas are destroyed after a few hours or days. The destruction of mandalas after a short time ties in with the Buddhist idea that nothing is permanent and things are always in a flux and one should not become too attached to things because they will disappear and bring unhappiness.

Mandalas as Meditation Aids

Buddhists use mandalas as aids for meditation. Both making a mandala and gazing at one are regarded as forms of meditation. The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung called mandalas universal maps of the human subconscious and "antidotes for the chaotic states of mind." He said their circular shape was a symbol of the divine.

Mandalas have three levels: 1) the outer level representing the universe; 2) the inner level showing the route to enlightenment; and the 3) secret level depicting the balance between the body and mind. Each shape is said to contain an attribute of a deity, and sometimes these shapes are used to forecast the future.

Mandalas aid individuals in visualizing various celestial Buddha realms. Two dimensional ones are regarded as part of the three— dimensional world of the central figure and a microcosm of the universe. During meditation a user using a mandala as a visual aid focuses on the deity, visualizing up to 722 deities associated with it, with the deity disappearing into nothingness and re-emerging as the deity. To do this takes extraordinary concentration.

Describing a 15th century mandala made by Newar artists at a Tibetan monastery, art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “it offers a labyrinthine, circles-within-squared topographic charts of heaven and hell, bristling with tiny sprits and monsters. A Tantric teacher, a guru, who knows the image, with its pitfalls and high places, will lead the committed student on a pilgrims progress to the mandala's center...There twin deities, male and female, are locked in an amorous embrace. The male is named Chakrasamvara, the female, Vajravarahi. Their intertwined bodies are the “The Circle of Bliss." Separately they represent the forces of wisdom and compassion; enlightenment is their union."

Difference Between Zen and Tibetan Meditation

On the difference Between Zen and Tibetan meditation, the Tattooed Buddha wrote: “Zen really emerged as a distinct sect when Buddhism entered China and Buddhist ideas merged with some of the Taoist philosophy that was already there. Tibetan Buddhism emerged when Buddhism entered Tibet and Buddhist ideas merged with the religion that was already present—a shamanic religion called Bon—that included a lot of things like nature spirits and ancestor worship. [Source: thetattooedbuddha.com =|=]

“Because that’s what Buddhism does. It mingles with whatever cultures are there already. Buddhism adapts to local conditions in a way that other religions don’t always. It’s a very versatile spiritual path. Zen Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism both have several different lineages that emphasize different things, so I can only really write about this in broad strokes right now...The really short answer is this: Zen Buddhism is minimalist and Tibetan Buddhism is much more elaborate.=|=

“Zen meditation is mainly about following the breath as well as emptying the mind. It also includes a few deeper things like meditative inquiry and riddles. Tibetan meditation often includes things like mantras and visualizations and concentrating on really complex thoughts. Tibetan Buddhism is more what we would think of as religious. There are a number of divine beings and Bodhisattvas that are talked about, visualized, and even prayed to. There are also very complex rituals and prayers. Zen Buddhism has rituals too. Practitioners are expected to bow a certain way and enter the temple a certain way, but things are just a less complicated. =|=

“And how are they similar? They both talk about lineage. Who your teacher was matters a great deal. They both emphasize Buddha nature—the teaching that we are Enlightened already—we just have to realize it. I don’t think one is better than the other. They are both authentic forms of Buddhism. If you like elaborate ritual, then Tibetan style is probably right for you. If you don’t, then Zen might be a better choice.”

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia, Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org , “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka lankalibrary.com “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); “ National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Source

[[1]]