DAKINI SCRIPT (Khandro Da-yig): Mysterious Symbolic Key to Hidden Treasures

<poem>

“Even just one symbol of Dākinī script can unlock in the treasure-revealer’s mind the entire teaching that is contained within it. They are the ‘passwords’ that allow the Terton to download the entire treasure of wisdom.”

Introduction

For today, the first day of the sacred Buddhist month of Saga Dawa, I offer a short research article on the mysterious ḍākinī script/symbols (called ‘Khandro Da-yig’ in Tibetan). The word for ‘ḍākinī’ is ‘kha-dro’ and ‘script’ is ‘da-yig’, which literally means ‘symbolic’ (da) ‘letters’ (yig) or ‘sign language’.

Within Vajrayana Buddhist cultures in Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan, stories of scriptural treasures, hidden away by Guru Padmasambhava are legion. In order to benefit beings in the future, Padmasambhava stored (or uploaded) ‘treasure; teachings in water, earth, rocks and space, as mind (gongter) or earth treasures (sater).

The ‘storage’ space has been likened by contemporary thinkers to the universal consciousness/field. The treasure stored there can only be unlocked and downloaded with two essential components: the treasure-revealer (Terton) and the female ‘key’ code and energy of a ḍākinī/consort. Often, treasures are written on

golden paper (ser shog) in the ḍākinī script, the code of which can only be deciphered by a Terton going into sexual union with a consort, or by someone who has the blessing of the body, speech and mind of Padmasambhava.

In this short post, as an introduction to this fascinating, yet generally uncharted, phenomenon, I pull together contemporary research and first-hand accounts of the ḍākinī symbols, their origin, function, appearance and the role of the ḍākinī and sexual union in treasure-discovery. Although a consort and union

is not always essential to reveal and decode treasures (as shown by HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche) there can be a tragic loss of treasure-revelation, if the Terton does not meet the right consort or loses the interdependent connections, as demonstrated by Terton Yongey Mingyur Dorje Rinpoche. I also consider some

recent advice by Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog in Tibet, who elaborates on both the importance of maintaining pure vows and commitments and the problematic aspect of (im)moral behaviour among non-celibate Tantric professionals (sngags pa khyim pa). Finally, this article also challenges the widely-held (and

unconsciously sexist) notion that Tertons are male and consorts are merely pretty, young females used as sexual objects. It is clear from history and experience that female treasure-revealers exist, some of whom had male consorts and some who didn’t. I have included biographical details of three famous twentieth-century female Tertons in Tibet and one living in Bhutan.

In this month of Saga Dawa, may this article be of benefit to beings and Dharma and lead to more treasures being revealed and understood and ultimate liberation on seeing!

Written and compiled by Adele Tomlin, 12th May 2021. With thanks to Khandro Kate for her inspiration and support.

8th Century, Indian Mahasiddha, Guru Padmasambhava said that all he realised will be important in the centuries to come. Recognising this, he preserved his teachings and wisdom in the form of terma (hidden treasures), to be found by qualified treasure-revealers at a degenerate time.

Terma can come in different forms. Terma are objects, texts or ḍākinī scripts, hidden in the air, space, earth, water by Guru Padmasambhava. Generally, the treasure revelations have come from Buddhist masters within the Nyingma tradition. However, as I wrote about here, some Karmapas and Kagyu masters have

revealed, and are lineage holders of hidden treasures, as are practitioners of other lineages. In January 2021, for example, the Jonang teacher, Khentrul Rinpoche, recently conducted an empowerment and ritual on a Jonang Tara (Drolmi Kazug) puja that was revealed from a mind terma of Lama Yonten Sangpo and Lama Lodro Drakpa.

People who are able to reveal these treasures are known as Tertons (gter ston). Treasures can be stored in material objects, such as rocks, water and so on. They can also be stored in space/mind. In the film, “Return of the Lotus-Born Master” Decrypting the Dakini Code – YouTube some of those interviewed compare this ‘space storage’ to the ancient Indian idea of the ‘Akashic Records’ or the notion of ‘universal consciousness’:

“That’s analogous to what’s called the Akashic records and the Akashic is an Indian word, it means sky so sky cloud. ”

“The Akashic records is is a library of the vibrational signature of everything that exists anywhere in the universe, and every thought that has ever happened.”

“Everything in the whole universe that ever happened, every thought that’s made, every intention that’s intended, is stored in the universal consciousness. That’s where collective unconsciousness comes from, you know there is no way for us to have that collective unconsciousness unless there is a storage system in the universe that’s beyond the individual, beyond individual time and space, a timeless aspect.”

Dākinī Symbolic Letters (Dayig) – the encrypted code

Origin and function

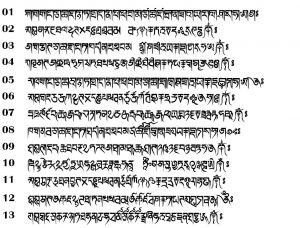

Termas are often written in what is termed, ḍākinī script (khandro Dayig). What is ḍākinī script? In brief, it is symbolic code, that once decoded, allow a treasure-revealer to download/unlock an entire hidden teaching (treasure). These Symbols cannot be understood by just anyone and are often written on yellow scroll paper (see image above):

“It could be a one-page written book or written teaching of guru Padmasambhava, but it will be written in ḍākinī letters. These letters condense the whole teaching into in a few words, or a single page, so that they have special letters or signs that not everyone can understand.” – Sonam Gyatso, Buddhist Scholar

“Even just one symbol of ḍākinī script unlocks in the treasure revealer’s mind the entire teaching that is contained within it. So, these are the passwords that allow the treasure revealer to download the entire treasure of wisdom.” – Christina Lee Monson, specialist on Ser Khandro

There has not been a huge amount of academic or field research done on this topic. One of the few contemporary scholars working on this subject is Bhutanese archeologist, Dr. Kunga Wangmo, who has conducted some research on the origin, meaning and function of the ḍākinī script. Wangmo was interviewed in the 2019 movie and says:

“Dākinī script could be a letter or just a few sentences that will unravel, or can be decoded into an entire volume of several volumes of text. When you have the key, you have access to the whole trove of information that underlies it.”

In 2016, Wangmo gave a presentation, Dākinī Script: Textuality, Transcendence, and the Role of Women in Vajrayāna Buddhism presented in Thimphu, Bhutan (see below). She summarises that:

“On an outer level the Dākinī Script are secret coded scripts or symbols that seals the Dharma to be revealed by the prophesized Terton. They are not necessarily written by the ḍākinīs or the Khandro. “

“How does one begin then to comprehend what Terton Pegyel Lingpa and his attendants, some of whom are still alive, that morning in 1969 at Paro Chumphu (which isn’t too far from here) when they saw water droplets

from the Dorje Phagmo (Vajrayogini) Lhatso Lake rise to form beautiful, but very strange string of scripts? Then, what about the Terton’s earlier discovery of Khandro Dayig, which he discovered from the bottom of a lake in Pema Ko? Or what about those that he found floating on a bamboo plant outside his patron’s house?”

“Many people think that the Dākinī Script (Khandro Da-yig) gets its name from the person who wrote the script. However, there are textual sources that say this is not necessarily the case. During the time of Guru Padmasambhava in Tibet, new special codes (da-yig) were created for the purpose of hiding important

teachings for the future. As writing all the important teachings for the future in longhand was both difficult and time-consuming, these secret coded writings were created and used. It is said that they were created in secrecy in Tibet and that they were used by very few and based on the U-chen of the Tibetan script. The Tibetan scripts were written by many, or all of the Guru’s core disciples, including Yeshe Tsogyel, under the instruction of the Guru himself. The ḍākinī Script are considered to be termas but also signs that lead the Terton to the precious terma. The Terton is already believed to have received the

teachings from the Guru in a previous life. The Khandro Dayig triggers recollection and they recall everything, whether in a trance-like state, or consciously when the signs appear because they are already familiar, even if subconsciously, with the teachings. Simplistically, people have likened the Khandro Da-

yig to a password that people use. The password unlocks the mind stream of the Terton from which the secret teachings arise. Simplistically, it has been likened to shorthand writing where each symbol or script or a

scribble can be stretched into words and phrases. Although again here each letter would produce volumes of scriptures, and this shorthand is so exclusive that only the designated Terton is able to decipher, unlike modern shorthand writing which all of us can learn but remember.”

Script’s Visual Appearance

Georg Fischer – collator of ḍākinī scripts

In a unique online resource (http://www.dakiniscripts.at/) created by an Austrian man, Georg Fischer (1940- ), he describes the ḍākinī Script as:

“The Terma scripts written by different calligraphers, human or non-human ḍākinīs and those written by Guru Rinpoche himself. Scripts written by Nyingma lamas, in form of deva nagari character (mkha’ gro’ brda’ yig), using their mystical writings, in a symbolic script. Different calligraphers with different calligraphic styles and designs. It is not unusual to find different representations for the same character.

The Nyingmas describe the Guru Rinpoche’s handwriting as thin and ravishingly beautiful, others are thick and smooth, or big and effectual in composition. There exist a lot of Terma scripts, common or uncommon, known as daka or ḍākinī scripts. But you don’t see the originals, they are all copies of old transcriptions.”

Fischer’s website has charts of fonts in a gallery explaining a total of 54 different scripts drawn on 20 old pecha woodblock prints. Some pechas are written in alphabets directly corresponding to the Tibetan alphabet. Some charts are attached by consonants adding vowels, other charts are without. In few charts are some ligatures or conjuncts.

In her 2016 presentation, although Wangmo does not cite a source, she explains three reasons why Guru Rinpoche used such scripts to hide the teachings, which are to preserve their ‘unaltered’ and ‘unmistaken’ purity:

“Guru Rinpoche concealed his most treasured teachings in this manner for three main reasons. He wanted the teachings when revealed by the intended person at the intended time to be transmitted with:

1) an unaltered sign (da ma cho);

2) an unaltered word (tshig ma cho);

3) unmistaken meaning (don ma nor)

The secret codes exists for the Terton and the Guru and are therefore inaccessible to ordinary beings like ourselves. The inaccessibility here extends not just to the spiritual and the literal meaning of the coded, secret scripts but the physical form of the scripts themselves. The Khandro Dayig are therefore created so that no one can manipulate or untie them besides the designated certain Dharma teachers.

Terma teachings are therefore considered extremely powerful because there isn’t a third party involved. It is exactly what the Guru said that is uncovered by the Terton, making it direct transmission.

Dr. Kunga Wangmo

Dudjom Rinpoche on the necessary qualifications of a Terton

Wangmo then explains what ‘lineages’ are required to be a Terton, citing a text by Dudjom Jigdrel Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche (bdud ‘joms ‘jigs bral ye shes rdo rje, (1904-1979) also a Terton), called the Dudjom Chojung. Dudjom Rinpoche was recognized as the incarnation of Dudjom Lingpa (1835-1904), whose previous

incarnations included the greatest masters, yogins and panditas such as Shariputra, Saraha and Khye’u Chung Lotsawa. Considered to be the living representative of Padmasambhava, he was a great revealer of the ‘treasures’ (terma) concealed by Padmasambhava. Dudjom Rinpoche’s second wife was Sangyum Kusho Rigzin

Wangmo, and they had four children, one son and three daughters. Their first daughter, Dekyong Yeshe Wangmo, was recognized as an incarnate ḍākinī and was believed to be an emanation of Yeshe Tsogyal, but died when she was a young woman.

Wangmo explained that “In a text by Dudjom Rinpoche, the Dudjom Chojung, History of Dharma, it mentions the three lineages from Padmasambhava required for the Terton, in addition to the three lineages already required, the Choba Sumdon, for Mahayana tantric Dzogchen teachings. These additional lineages are Melong

Uche Chopa, where the Guru makes aspirations for the Terton. Kabab Lungten gi Chopa, where the Guru identifies these special people for the specific special task and then empowers them. Khandro Tercho ki Chopa is where the Guru empowers various Khandros or ḍākinīs to become keepers or protectors of the Da-yig which seals his important teachings, and thus invariably tying the Khandro’s destiny to that of the Terton.

So it isn’t any ordinary Buddhist practitioner, it’s not even any high Lama who gets access to the symbolic script. They have to definitely have those three extra lineages from the Guru himself: the person has to be wished for, he has to be chosen and empowered and prophesized by the Guru himself.”

As HE Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche ((1955- ) considered to be the 9th body and activity incarnation of the famous Terton, Pema Lingpa) says in the 2019 movie:

“To read the ḍākinī symbolic letters, one needs to blessed by the body, speech and mind of Guru Padmasambhava. If one is not a terton (treasure-revealer) no matter how educated one cannot decipher the ḍākinī script.”

Terrone in his paper on Treasure-revelation says:

“I would conclude that, in terms of taxonomical formulations, Treasure revealers’ authenticity springs mainly from three sources. First of all, a Treasure revealer’s claimed and/or recognised link with his past as one of the principle disciples of Padmasambhava; second, his realisation as a true Tantric practitioner;

and third, the quality and comprehensive nature of his revealed Treasures. The latter, as we have seen above, entails an accurate investigation of the Treasure revealer’s gter chos, which should ideally be a broad collection of the three major bla rdzogs thugs cycles of practice. The one who investigates a

Treasure revealer’s authenticity must be an exceptional Buddhist master. This, however, seems to be appropriate as a posteriori type of investigation, whereas the a priori investigation of a Treasure revealer is instead given to the

force of prophecy and vision. These seem to manifest predominantly before the would-be Treasure revealer has begun his career and produced entire cycles of practice according to his mandate.”

Note how Terrone uses the word he to describe Treasure-revealers though, many of whom are females (see below).

Role of the Khandro/Dākinī in unlocking the treasure and the script

There is a widely-held (and unconsciously sexist) notion that Tertons are male and consorts are merely pretty, young females used for their bodies It is clear from history and experience that female treasure-revealers exist, some of whom had male consorts and some who didn’t, for more on that see below. However, when talking about khandro ḍākinī, generally they are biologically female (for more on gender and biology in tantric union, see here).

There are several definitions and types of ḍākinī within the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. They are difficult to ‘put a finger on’ and ultimately represent wisdom. Tsultrim Allione (considered to be a direct emanation of Machig Labdron) speaks about ḍākinīs and ḍākinī power here:

It is clear that male Tertons often relied on female Khandro consorts, to reveal and decipher treasures. In the 2019 movie, several people assert that union with a ḍākinī consort was vital to not only discover, but also decrypt, the ḍākinī script:

“Without the Khandro the treasure-revealer would not be able to find the dharma that needs the conduct to help receive.”

“The dharma feminine consort also acts as a tuning fork at a higher frequency, so basically the female Khandro activates the female energy within.”

Dr. Wangmo considers this question in her presentation and asserts that on of the primary roles of the ḍākinīs is as exclusive keepers of the Terma:

“What is the role of the Khandro in it all? This tradition of the Khandro ḍākinīs being keepers of Dharma and special sites are not specific to Guru Rinpoche alone. In fact, the word ḍākinī itself is of Dravidian, not Sanskrit origin. The Draividians worshipped the feminine and associated power places with the ḍākinīs,

before the Aryans invaded and took over the Indian subcontinent around 4000 BC. The Aryans then adopted these power places and associated them with their own gods Ishvara or Shiva. When Buddhism came on to seen the ḍākinī code the Ishvara ḍākinī cult was already in full swing, practicing blood sacrifice. The Buddha,

to counter this negative aspects of the ḍākinī cult, is believed to have gathered together the ḍākinīs and encouraged them to renounce their practice of blood sacrifice. He restored them to their original purity

and saw them as Dharma protectors. So what is clear is the ḍākinīs have been made keepers of the Dharma. They were chosen and empowered by the Guru, just as the Tertons are. One can imagine the Terton and the Khandro having a key each to the same lock, both of which are required to unlock and unseal the Dharma.”

The Role of Sexual Union in Terma Discovery

Dr. Wangmo then explains how tantric union has been necessary for Tertons to discover the treasures, with a story of how the famous Terton Chogyur Lingpa wanted union with a consort on a boat. Although Wangmo refers to it as ‘sex’ in her talk, it clearly is not ordinary sex but involves a sacred tantric union. She says:

“Besides being keepers of then Dharma, there is also the element of tendrel (interdependence) that a ḍākinī brings to the discovery. It is often said that a Terton cannot reveal his terma if the interdependence (tendrel) are not right. There is significant emphasis on the presence of a Khandro or feminine body. Many

understand the Khandro here to be a lady who is sexually involved with the Terton, a consort or a young, beautiful desirable woman. On the outer level, the physical Khandro is very important indeed. There are many stories of their revelations that talk about the Sayum (Earth mother) or Teryum (Treasure mother)

being present, and the absence of which makes it impossible for the Terton to discover the Terma. This is true in the case of the prolific Terton Chogyur Lingpa (1829-1870) who, as many of you know, discovered the Guru Kutshab of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo/ At one point, he needed to have sexual union with his Khandro at

a specific time and place, and that specific time and place being on a boat in the middle of the river while crossing it. The Khandro of course refused it because there were other travelers with them. This was believed to have broken the tendrel and so the Terton wasn’t able to reveal his Terma.”

The Khandro does not have to be a sexual consort either

Wangmo also says:

“There are many examples of Khandro being a little girl or a very old lady. In the case of the first Hefu (?) tulku, Ngawang Dragpa who was a support Terton for Pema Lingpa, the Khandro Yeshe Tsogyel herself, appears in Ngawang Dragpa’s, vision and reminds him rather harshly, by slapping him across his face, and

asking him to go get his Terma. Ngawang Dragpa eventually goes to Khyichu Lhakhang and recovers a Guru Kutsab, which is a guru statue from the chest of the Jordey. Then there are monastic Tertons, like Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo and the fifth Dalai Lama. There are also female tertons such as Kunga Bumpa and Jomo Menmo, who were also visited in their dreams and meditational visions before revealing a Terma.”

Not much has been written or investigated in English about how or why the energy of the sexual union unlocks the treasures. My own initial thoughts on it, based on my experience of tantra and consort union, is that the tantric union and the bliss that is generated within that, somehow creates and enters into the ultimate, blissful energetic expanse and energy (of the ultimate expanse) which ‘opens’ up the treasure stored within that.

Antonio Terrone, talks about the (im)morality, sexual aspect of contemporary treasure-revelation in a paper called Anything is an Appropriate Treasure Teaching: Authentic Treasure Revealers and the Moral Implications of Non-Celibate Practice:

“Today in Tibet, despite the obvious changes brought about by the new socio-political geography and the new challenges triggered by the religious policy of the PRC, Treasure revealers are still active and revelation

and visionary activities continue to be a visible aspect of Tibetan lived religion. Just as in the past, issues concerning authentic Treasure revealers and the moral implications of their lifestyles and activities are still at the centre of debates. For instance, Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog (Mkhan po ‘Jigs med

phun tshogs) remarked on this issue in a series of oral instructions addressed to both monastics and laypeople that he gave publicly at Larung Gar (Bla rung sgar) in 2000/2001. Recently, his disciples collected this advice into a booklet, the Zheldam (Zhal gdams). Discussing the importance of maintaining

the pure and untainted vows, he offers his opinion on the moral choices at stake within the ‘two systems’ (lugs gnyis), the religious system (chos lugs) and the secular system (srid lugs). He describes these as the ‘saffron monastic community’ (rab byung ngur smrig gi sde) and the ‘whiterobed group with long hair’ (gos dkar lcang lo’i sde) respectively.”

Terrone focuses on the third chapter titled ‘Straying from the holy and sublime Dharma’ (dam pa lha chos dang sbyar nas ‘chad pa), in which he says Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog elaborates on both the importance of maintaining pure vows and commitments and the problematic aspect of (im)moral behaviour among noncelibate Tantric professionals (sngags pa khyim pa). He says:

“Interestingly, after having defined the criteria for determining who can be an authentic Treasure revealer in the Zhal gdams, Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog’s observations then switch over to moral behaviour. A major criticism that he specifically directs against noncelibate Tantric specialists and Treasure revealers concerns their sexual misconduct (spyod ngan). Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog criticises the custom many of them

practise of having multiple consorts. Additionally, he is also very critical of their laxity and immoral behaviour for indulging in drinking and sensory pleasures under the pretext of acting in accordance with their Tantric training. Again, in his Zhal gdams Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog elaborates on noncelibate Tantric professionals and Treasure revealers proclaiming:

“Without any knowledge of winds, channels, and seminal nuclei but motivated by desire deceived as necessity, they (the sngags pas and gter stons) engage with many women. Despite being absolutely devoid of

any of the fundamentals of the generation and perfection phases they engage [in the practice of liberating/killing enemies by the wrathful application] of the karma of destruction motivated by hatred. Also, motivated by desire, they make unrestrained use of servants.” (p.473).

Thus according to Terrone, “Khenpo Jigme Phuntshog favoured monasticism and the precepts of the vinaya code and refused the use of consorts, knowing that renouncing the practice with a consort would affect his revelations. According to him, only those who truly persevere towards the path of realisation by exerting themselves in the accomplishment practice (bsnyen sgrub) can be real Treasure revealers.” (p475).

“Recently, in her study of the great female Treasure revealer Sera Khandro (Se ra mkha’ ‘gro (1892-1940)), Sarah Jacoby has pointed out how consorts play an important role in revelation. In her words: “Treasure revelation is founded upon a Tantric understanding of the body in which mental realisations are

generated from manipulating the channels, winds, and seminal nuclei of the subtle body (rtsa, rlung, thig le). Unique to the Treasure tradition is the link between the generation of textual and material Treasures

and the biologically generative act of sexuality. Specifically, the role of the female consort is linked to Yeshé Tsogyal’s mnemonic and encoding powers; female consorts aid Treasure revealers in their process of decoding the Treasure’s symbolic scripts.”

According to Terrone, contemporary treasure-revealers in Tibet have confirmed the importance of consorts in treasure-revelation:

“Such a view is also confirmed by current Treasure revealers. According to Tashi Gyeltsan (Bkra shis rgyal mtshan), a consort (thabs grogs) is an important companion for a Treasure revealer’s practice, although it is not the condicio sine qua non of Treasure revelation. A Treasure revealer can still reveal Treasures,

especially material objects such as earth Treasures (sa gter) without a consort, and a few can even become great Treasure revealers, as in the case of Mkhan po ‘Jigs med phun tshogs and Grub dbang lung rtogs rgyal mtshan (a.k.a. Mkhan po A chos). However, as Tashi

Gyeltsan’s comments clearly illustrate in the following passage, in the process of Tantric practice the cooperation of a consort can increase the Treasure revealer’s chances to reveal more Treasures, especially mind Treasures:

“If a high being who is a Khandroma unites with a great Treasure revealer of superior birth they will get great achievements and then they will be able to retrieve many Treasures. This is known as ‘auspicious connections of method and wisdom’ (thabs shes kyi rten ‘brel) and it is also called the ‘true nature of the

auspicious connections’ (rten ‘brel gyi chos nyid). Then, for instance, if there is a teacher who is a Treasure revealer without a consort, he will be like a single person having only the power (shugs) of one person being without a partner, since the double power coming from a couple will not be possible.” (476)..”

HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s Termas

Although it is clear that many treasure-revealers had consorts, it was not always necessary. One such example is that of the Vajrakilaya treasure revelation by HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-1991) (as I wrote about before here). In the recent movie, Dilgo Khyentse’s grandson, student and Vajrayana master, HE Schechen Rabjam Rinpoche spoke about how this treasure was revealed and the ḍākinī script deciphered by placing it in water:

“Once, there was a ḍākinī script that was not yet revealed, so they engaged Dilgo’s help. It was just one single tiny page. Dilgo obliged. He went to a shrine (stupa) and asked for a cup of alcohol of which he mixed with nectar. Next, he added some blessing pills and the ḍākinī script into the mixture. He then

conducted his rituals and peeped at the cup from time to time. After awhile, he asked for paper. He was given 40 sheets of paper—paper was valuable at that time—and he filled all 40 sheets with writings. As soon as he was done, the writing on the ḍākinī script disappeared. He said you have me 40 sheets of paper, so I wrote 40 sheets. Perhaps if he had been given more paper, more would have been written.

On another occasion, Dilgo was at a holy site in Tibet. Some commotion ensued and something rolled down from the sleeve of the Dharma Protector statue and landed in front of him. It was a ḍākinī script. Based on that script, he wrote a whole cycle of the Vajrakilaya practice.”

Terton Yongey Mingyur Dorje and his loss of the right consort

Lack of the right consort can be catastrophic to a Terton. As I wrote about here before, one example of this, comes from the life of Terton Migyur Dorje (gter ston mi ‘gyur rdo rje (1645-1667)). In the book Chariot of the Fortunate: The Life of the First Mingyur Dorje by Je Tukyi Dorje & Surmang Tendzin Rinpoche,

(2005), contains a brief biography of Mingyur Dorje by Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, extracted from his Lives of the Hundred Treasure Revealers. The book contains an interesting tale of the ‘great loss’ that happens when a treasure-revealer, Yongey Mingyur, ‘loses the interdependence of getting the correct treasure-consort woman (pp.31-32):

“His principal destined treasure consort was Adrama, a niece of Jamo of Lhateng. Adrama, however, was challenged. She was lame in both arms and legs, and she did not respond to language. The treasure revealer requested that she be given into his care. He went to Lhateng bearing an antique belt of conch that must have been discovered as treasure, inscribed with representations of the eight auspicious substances, as a

gift. Adrama responded to his presence with a display of pleasure. But Jamo decided not to give her into the treasure revealer’s care. The treasure revealer took back the belt. He then dressed two mounds of snow in a set of Adrama’s clothing and a set of his own, and placed hair from each of them in the respective mounds. He then burnt them. He also cut off most of his hair, which he had worn long until then, and burnt it as well. He said:

“Unable to meet Tsogyal’s emanation, Uddiyana’s emanation has discarded his locks. Tibet’s merit is diminished.”

It is said that it was on that day that he began to act as though crazy. In any case, it is certain that it began at around that time. It is also said that both Adrama’s mother and her uncle, Jamo Lama, possessed supercognition, but that, when it could have been of the greatest use, they were overcome by the vanity of possessing it and made the wrong decision.

From one perspective, it appears that the treasure revealer’s subsequent behavior arose from the disintegration of interdependence. From another, I am certain that he was engaging in the conduct that brings progress on the path, the behavior of someone who has destroyed mundane bewilderment.

For one year after he began this behavior he remained alone, without even any attendants. Of his seven former attendants, two went to Tsurphu to request the support of the Karmapa, Yeshe Dorje. The Karmapa responded to their request by saying, “Mingyur Dorje is a mahasiddha who has destroyed bewilderment. He is not insane. Gather his attendants together as before and obey his every command as in the past.”

The attendants returned to his service. Thereafter, the treasure revealer lived as a nomad. He took Dontarma as wife, and later Jochungma. Had the interdependence of his treasure consort and so forth transpired successfully he would have come to possess a hundred treasure dharmas. It is said that his

destined treasure sites included Gowo Cave in Dzagyal, Karma Legak, the rock near Dzato that bears the imprint of a horse’s hooves, a place called Lords of the Three Families, a place called Garama Rock in Danak, and Turquoise Lake in upper Domredo. His treasures would have included endless varieties of life

sadhana and so forth. What transpired was in accord with the merit of the doctrine and beings in these evil times. Nevertheless, it appears that he did reveal a few additional minor treasures, such as mind treasures, sky dharma, and lake treasures.”

Female Treasure-Revealers

It is not necessary for the Terton to be male and the consort to be female. Although most Tibetan Buddhist literature is about the lives and works of male treasure-revealers, that is now changing with contemporary English language scholars, such as Tsultrim Allione, Holly Gayley, Sarah Jacoby and Hanna Havnevik,

publishing excellent research on the lives of female realised masters and Tertons. Below are three recent, twentieth century examples of women who were renowned Tertons and accomplished Buddhist practitioners. All of them experienced extreme hostility and rejection, of one sort or another, from within the communities they lived.

Sera Khandro, Kunzang Dekyong Wangmo (1892-1940)

One of the most well-known examples of a female terton nowadays, due to the research efforts of academics, such as Dr. Sarah Jacoby, is that of Sera Khandro. In the Treasury of Lives biography by Jacoby:

“Sera Khandro later became the consort of Gara Gyelse (mgar ra rgyal sras), son of the treasure revealer Gara Terton Dudul Wangjuk Lingpa (mgar ra gter ston bdud ‘dul dbang phyug gling pa, 1857-1911) of Bennak Monastery (ban nag/pan nag) in Golok. They had two children, a daughter named Yangchen Dronma / Choying Dronma (dbyangs can sgron ma / chos dbyings sgron ma, b. 1913), and a son, Rigdzin Gyurme Dorje (rig ‘dzin ‘gyur med rdo rje, 1919-1924), who did not live past childhood.

Life with Gyelse proved difficult for Sera Khandro; he disapproved of Sera Khandro’s calling as a treasure revealer and forbade her from writing or propagating religious teachings. Her health worsened as she became increasingly afflicted with an arthritic condition in her legs. Meanwhile, her devotion for Drime Ozer only grew stronger. These factors contributed to Gyelse’s decision to send her back to live with Drime Ozer when

she was twenty-nine years old. Sera Khandro credited her reunion with Drime Ozer with curing her of her illnesses. Together they revealed many treasures. After Drime Ozer’s death only three years later, his disciple Sotrul Natsok Rangdrol (bsod sprul sna tshogs rang grol, d. 1935) invited Sera Khandro to live at his monastery in Golok named Sera Monastery, the place from which she derives her title.

Sera Khandro traveled widely throughout Golok with her attendants, the monks Tubzang (thub bzang) and her scribe Tsultrim Dorje (tshul khrims rdo rje). Her main teachings were the treasures of Dujom Lingpa and Drime Ozer as well as her own. She died in Riwoche at the age of forty-eight. It is said that before her body was burned, it dissolved into light until it was the size of a seven-year-old child’s body.”

Semo Saraswati, the daughter of Jadral Rinpoche is recognized as the tulku incarnation of Sera Khandro.

Tāre Lhamo (1938-2003)

Tāre Lhamo aka Tāre Dechen Gyalmo (tva re lha mo bde chen rgyal mo, 1938–2003) was a Tibetan Buddhist master, visionary, and treasure revealer (gter ston) who gained renown in eastern Tibet. She was especially praised for her life-saving miracles during the hardships of the Cultural Revolution and for extending the life-span of many masters. It was said that her activities to benefit others swelled like a lake in spring.

At age 40, Tāre Lhamo became the wisdom consort of Namtrul Rinpoche Jigme Phuntsok, aka Orgyen Namkha Lingpa (1944–2011), the Fourth Namkai Nyingpo and the rebirth of her father, Apang Terchen. The eminent couple worked tirelessly to restore and expand religious study and practice in their communities. Their home base was Nyenlung in Serta County, Sichuan, close to Dodrupchen and Larung Gar.

Tare Lhamo discovered many Secret Mantra and Dzogchen Dharma treasures (gter chos), including sadhanas, songs of birds, and songs of realization. Together with Namtrul Rinpoche, their collected works of 600 plus texts are published in Tibetan. According to Tulku Orgyen Zangpo Rinpoche, one of her treasures was about tying different types of knots with string as a skillful means of accomplishing wishes or activities to

benefit others. “Khandro had a hundred different types of knots she used for different purposes, such as longevity. Or, if you were sick or had obstacles or wanted a son or daughter.” Jetsunma Kunga Trinley Palter Sakya was born January 2, 2007, as the daughter of Dagmo Kalden Dunkyi and Ratna Vajra Rinpoche, the current Sakya Trizin, whose father was the rebirth of Apang Terton. The Dalai Lama has recognized her as the rebirth of Tare Lhamo.

Shukseb Jetsunma Chönyi Zangmo (1852–1953)

Shukseb Jetsunma Chonyi Zangmo (rje btsun rig ‘dzin chos dbyings bzang mo) was one of the most well known of the yoginis in the 1900s, and was considered an incarnation of Machig Lapdron. She was the abbess of Shukseb nunnery, and was a Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist teacher. She made the nunnery once again into a center for the special teachings of the Shukseb Kagyu. The nunnery still exists in Tibet today, and in fact is one of its most active nunneries. There is also now a Shukseb nunnery in exile in Dharamsala, India.

Her Treasury of Lives biography states that she faced huge amounts of hostility and violence for her increasing signs of realizations and spiritual power:

“Chonga Lhamo remained with Pema Gyatso when he moved his disciples to Nubri Valley, but there she seems to have run into trouble, no doubt connected to her growing confidence in her practice; charismatic women in Tibet were almost universally viewed as threats by male lamas. Pema Gyatso beat her for alleged arrogance. He branded her on her forehead with a hot iron and banished her to Pokhara in Nepal. She eventually was

able to return, and rejoined the group at Thak. There she began to have revelations, supposedly having visions of treasure texts and receiving from a local deity birch bark and ink to record them. A male teacher named Chozang (chos bzang) kicked her in the head and burned her writings, forbidding her from ever

speaking of them. Pema Gyatso’s male disciples maintained a hostile environment for her, refusing to allow her to visit Pema Gyatso’s own teacher, Dharma Sengge (khams smyon d+harma seng ge) when the elder lama was dying, and they refused to give her the objects the lama had bequeathed her.”

Yet, still she persisted! She was considered to be an emanation of the Chod founder and lineage holder, Machig Labdron, and Chod is practiced regularly at the Shukseb nunneries:

“In about 1904, Rigdzin Choying Zangmo moved to Shukseb Monastery in the district of Chushur (chu shur) in the south-west of Lhasa, where the Lhasa and Yarlung rivers flow together. The monastery had been founded in 1181 by Gyergom Tsultrim Sengge (gyer sgom tshul khrims seng+ge, c. 1122-1240) and was run as a Kagyu

institution and the seat of the Shukseb Kagyu tradition. The location is also said to have been a practice site of Machik Labdron (ma gcig labs sgron, 1031-1129). Just above Shukseb is Gangri Tokar, (gangs ri thod dkar) an important activity site of Longchen Rabjam Drime Ozer (klong chen rab ‘byams pa dri med ‘od zer, 1308-1364). Pema Gyatso had considered it for his residence back in the 1880s when he settled in the Lhasa area.

When Rigdzin Choying Zangmo arrived at Shukseb the administration of the site was apparently a matter of controversy and the monastery was in disrepair. She and her followers spent years rehabilitating the site, collecting donations from nearby families.

Around 1912 she gave a Chod empowerment at Shukseb according to the tradition of Machik Labdron to a gathering of about hundred devotees. She frequently engaged in Chod practice and at numerous points in her life she was recognized as a manifestation of Machik Labdron.”

Khandro Dorje Phagmo

In a recent article about a living female Terton in Bhutan, Khandro Dorje Phagmo, it says:

“The five principal spiritual consorts of Guru Padmasambhava were emanations of Dorje Phagmo: Mandarava from Zahor, an emanation of body; Yeshi Tshogyal from Tibet, an emanation of speech; Sakya Devi from Nepal, an emanation of mind; Kalasiddhi from India, an emanation of quality; and Tashi Kheudren from Bhutan (known as Mon in those days), an emanation of activity.

Several reincarnations of Dorje Phagmo have been recognized in Tibet since the medieval era, the first being recognized by the mahasiddha Thangtong Gyalpo, which began the lineage of Samding Dorje Phagmo in the 15th century. In the hierarchy of Tibetan Buddhist figures, Samding Dorje Phagmo is considered the highest female incarnation.

The prophecy of the birth of the present incarnation of Dorje Phagmo was made by none other than the great 20th century yogi Lama Sonam Zangpo (1888–1982). In 1974, Drubthob Thangthong Gyalpo Rekey Jadrel Rinpoche shared the following prophecy with Dudjom Jigdrel Dorje Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Kalu Rinpoche, and other realized masters:

A baby girl, an emanation of Dorje Phagmo, will be born. She will be of great benefit to all beings but she will encounter great obstacles. If she did not meet these obstacles, her activities in the world to help all beings would be even more profound. The reason for these obstacles is that sentient beings lack sufficient merit at this time.“

As a child she took empowerments and studied with Kalu Rinpoche. Then on the advice of Druktruel Ngawang Khenrab and Ayang Rinpoche, she was sent to Mysore in India in 1988 to study under His Holiness Pema Norbu (known as Penor Rinpoche; 1932–2009). For 12 years thereafter, Dorje Phagmo studied at Namdroling Monastery and received every teaching and empowerment from Penor Rinpoche, who also recognized her as a true incarnation of Dorje Phagmo.

During her studies in Mysore, Dorje Phagmo was diagnosed with a form of blood cancer. The medical prognosis was not favorable: she was not expected live longer than a few months. The illness brought with it a nightmare of difficulties, witnessed by a few attendant devotees at Changidaphu (Kala Bazaar), Thimphu. Today we are all fortunate that the cancer prognosis and medical tests have proven to be incorrect.

In 2000, after completing her studies, Dorje Phagmo returned to Bhutan to spend two years in solitary retreat at Paro Tashi Chhoeling Monastery.”

Today, Dorje Phagmo Rinpoche continues her work spreading the Dharma, spending much of her time at her monastery in Zhemgang District, with occasional visits to Thimphu to raise the necessary resources and to meet with visitors and followers.

Since returning to Bhutan, Dorje Phagmo Rinpoche has revealed and discovered numerous ter (sacred treasures), and is said to have manifested several miracles in person, such as leaving her hand and footprints on rocks, pebbles, and wooden floors, and spending nights alone practicing in places such as Buli Tsho (Buli Lake), and helping people recover from chronic illnesses. Many of her devotees have witnessed these events in person, and all of these people are living and can testify to their experiences.”

Further Reading

Allione, Tsultrim. 2000. Women of Wisdom (2nd revised edition, Shambhala).

Doctor, Andreas. 2005. Tibetan Treasure Literature: Revelation, Realisation, and Accomplishment in Visionary Buddhism. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications.

Gyatso, Janet. 2005. Sex. In Donald S. Lopez Jr. (ed.), Critical Terms for the Study of Buddhism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 271–90. —— 1998. Apparitions of the Self: The Secret Autobiographies of a Tibetan Visionary. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jacoby, Sarah H. 2007. Consorts and Revelation in Eastern Tibet: The Auto/Biographical Writings of the Treasure Revealer Sera Khandro (1892– 1940). Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Virginia.

Terrone, Antonio. 2008. Tibetan Buddhism Beyond the Monastery: Revelation and Identity in rNying ma Communities of Present-day Kham. In Monica Esposito (ed.), Images of Tibet in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Paris: École Française d’Études Orientales (EFEO), Coll. «Études thématiques» (22.2), 2008, pp. 746-779. —— 2002. Visions, Arcane Claims and Hidden Treasures: Charisma and Authority in a Present-Day Gter ston. In C. Klieger (ed.), Tibet, Self, and the Tibetan Diaspora. Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 9th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Leiden: Brill, 213–28

Anything is an Appropriate Treasure Teaching: Authentic Treasure Revealers and the Moral Implications of Non-Celibate Practice.

Thondup, Tulku. 1990. The Terma Tradition in the Nyingmapa School. The Tibet Journal, XV(4), 149–58. —— 1986. Hidden Teachings of Tibet: An Explanation of the Terma Tradition of the Nyingma School of Buddhism. London: Wisdom Publications. Ye-śes-mtsho-rgyal. 1978. The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava. Emeryville: Dharma Publishing.

Young, Serenity. 2004. Courtesans and Tantric Consorts: Sexualities in Buddhist Narrative, Iconography, and Ritual. New York and London: Routledge.

Sera Khandro

Jacoby, Sarah. 2009. “To be or not to be Celibate: Morality and Consort Practices According to the Treasure Revealer Sera Khandro’s (1892-1940) Auto/biographical Writings.”In Jacoby, Sarah, and Antonio Terrone (eds),Buddhism beyond the Monastery: Tantric Practices and their Performers in Modern Tibet. Leiden: Brill.

Jacoby, Sarah. 2009-2010. “This Inferior Female Body:’ Reflections on Life as a Treasure Revealer Through the Autobiographical Eyes of Se ra mkha’ ‘gro (Bde ba’i rdo rje, 1892-1940).”Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, vol. 32, no. 1-2, pp. 115-150.

Jacoby, Sarah. 2014. Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro. New York: Columbia University Press.

Tare Lhamo

Gayley, Holly, Love Letters from Golok: A Tantric Couple in Modern Tibet, Columbia University Press, 2016. Gayley, Holly, Inseparable across Lifetimes: The Lives and Love Letters of the Tibetan Visionaries Namtrul Rinpoche and Khandro Tare Lhamo, Snow Lion, 2019, https://www.shambhala.com/inseparable-across-lifetimes… Gayley, Holly, Khandro Tare Lhamo https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Tare-Lhamo/8651

Orgyen Zangpo Rinpoche, Life of Khandro Tāre Lhamo, interview with Lama Dechen Yeshe Wangmo, Jnanasukha Foundation, http://www.tarelhamo.com/videos

The Life & Works of Tare Lhamo

Shukseb Chonyi Zangmo

“The Story of a Tibetan Yogini: Shungsep Jetsun 1852-1953” prepared by Kim Yeshi and Acharya Tashi Tsering with the assistance of Sally Davenport and Dorjey Tseten, pp. 130-143, Chö Yang, 1991

Shugsep Jetsun, the Story of a Tibetan Yogini https://tnp.org/shugsep-jetsun-the-story-of-a-tibetan-yogini/

Havnevik, Hanna. (2005) “Ani Lochen”. Encyclopedia of Religion. Second Edition. Ed. Lindsay Jones. New York: Macmillan. http://www.hf.uio.no/ikos/english/people/aca/hannah/

Havnevik, Hanna (1999) The Life of Jetsun Lochen Rinpoche (1865-1951) as Told in Her Autobiography. Acta Humaniora, Faculty of Arts, University of Oslo. Dissertation for the degree Dr. philos. 1999.

Havnevik, Hanna (1998) “On Pilgrimage for Forty Years in the Himalayas. The Female Lama Jetsun Lochen Rinpoche’s (1865-1951) Quest for Sacred Sites.” In Pilgrimage in Tibet. Ed. Alex McKay. Richmond: Curzon Press. (pp. 85-107)

Written and compiled by Adele Tomlin, 12th May 2021. Copyright. Please share and re-publish with source cited.

Source

[[1]]