Chod -- the Tantric Practice of Cutting through Attachment

Chod, meaning cutting through, is a Buddhist Tantric practice. Although it is rooted in Buddhist teachings transmitted from India, its main features were molded by the Tibetan Yogini Machig Labdron (1055-1153) based on her insight and spiritual experiences. On the transcendental and supernatural level, she received blessings directly from the primordial enlightened mind

manifesting as holy beings to originate these tantric teachings for the salvation of all beings. Although India is the birth place of Buddhist teachings, Chod stands out as the only teaching that was molded anew in Tibet and then spread to its neighboring areas including India. It has been a wide-spread practice adopted by monks, nuns and laity alike, especially by devout beggars and

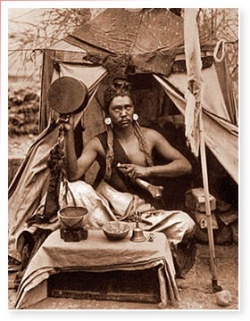

wondering yogis who travel from cemeteries to desolate places and never stay at one place for more than seven days. Many systematic and unique teachings on Chod, complete with rituals, precepts, visualizations, and instructions about stages of realizations are well-preserved by many lineages up to this day. For details on its history, lineage and spreading, please refer to Jerome Edou’s book listed in the References.

1. A General Characterization of Chod

Recognizing the body as the root of one’s attachment to self, Machig Labdron formulated Chod to be a practice that would destroy this fundamental attachment and simultaneously develop compassion for all beings. The main part of a Chod practice can be outlined as follows:

- A. Transfer one’s consciousness into space and identify it with the black Vajra Yogini.

- B. Through visualization, identify the body with the universe and then offer it completely to all beings who would want them, especially one’s creditors, enemies, and evil beings.

For details, please refer to Chapter III below for an example of a Chod ritual.

To handle worldly or spiritual problems there are many types of approaches. Some try to dissolve the problems, some plan to escape from the problems, some attempt to stay at a safe distance and tackle through theoretical discussions, and some would face the problems and work on them. When one is not ready to handle the problems, the first three types of approaches are temporarily appropriate; nevertheless, the ultimate test of a solution lies with the head-on approach.

Chod is obviously a head-on approach to the spiritual problem of subconscious attachment. It also exemplifies the ultimate wisdom of facing the reality to realize its conditional nature instead of being satisfied with merely conceptual understanding. Chod is learning through enacting. One’s attachment to the body, fear of its destruction, greed for its well-being, and

displeasure for its suffering are all put to test in a Chod practice. When all these subconscious mental entanglements are brought to light through the visualization of dismemberment, one is really fighting with one’s self. No one who cannot pass the test of such visualizations would have a chance of achieving liberation under real-life circumstances.

Advanced Chodpas (practitioners of Chod) do not satisfy themselves with just the ritual practices. They often stay in cemeteries, desolate places, and haunted houses in order to face the fearful situations and experience the interference from desperate or evil spirits. By developing compassion for all beings, including those trying to scare or harm them, by sharpening wisdom through realizing the [[non-

substantial]] nature of fearful phenomena and fear itself, and by deepening meditation stability through tolerating fearful situations, Chodpas gradually achieve transcendence over attachments, fear, greed, and anger. Through the hardship of direct confrontation they advance, step by step, on the path toward Enlightenment.

The separation of the consciousness from the body indicates the mistake of identifying with the body. It is the aboard of this life; both this life and its aboard are transient and cannot be grasped for good. The identification of the consciousness with the black Vajra Yogini signifies the recognition of the wisdom of non-self. On one hand, the black Vajra Yogini is a manifestation of the

primordial wisdom of non-self; and on the other hand, due to the non-self nature of both the consciousness and the Yogini, they may be identified. Furthermore, the identification with the black Vajra Yogini, as it is the case in all tantric identification with a Yidam, is not grasping to a certain image but involves salvation activities. In other words, it is a dynamic approach to personality changes.

On the surface Chod seems to be an offering of only the body. Nevertheless, during the visualization the body has been identified with the universe, and consequently the offering means the offering of all things desirable. Thus, Chod is not just aiming at reduction of attachment to the body but also of all attachments. In terms of the traditional tantric classification of four levels,

Chod could be characterized as a practice which frees one: outwardly from attachments to the body; inwardly, to sensual objects; secretly, to all desires and enjoyments; and most secretly, to self-centeredness. A Chodpa would gradually experience the transforming effects of Chod practices and become aware of its ever deeper penetration into the subtle and elusive core of one’s attachments.

2. The Essential Ingredients of Chod

Chod as a tantric practice consists of the following essential ingredients:

A. The Blessing of the Lineage

In Tantric Buddhism lineage, meaning an unbroken line of proper transmissions of the teachings, is essential to practice and realization. This is because what is transmitted is not just the words but something spiritual and special. Through proper transmissions the blessings of all the generations of teachers are bestowed on the disciples. Without such blessings no one can even enter the invisible gate of Tantra. Tantric practices without the blessing of lineage may be likened to automobiles out of gas.

In Tantric Buddhism lineage is always emphasized and the teachers are revered as the root of blessings. In Sutra-yanas the importance of lineage is often overlooked by scholars who lack interest in practice and ordinary Buddhist followers. This is probably the main reason why in Tantric Buddhism blessings can often be directly sensed by practitioners while in Sutra-yanas such experiences are less frequently encountered.

All tantric practices derive their special effectiveness from the blessing that is transmitted through the lineage. In the case of Chod, the blessing from Machig Labdron is the source of such blessings. All other teachers that form the various lineages of Chod are

also indispensable to the continuation of these lineages; without their accomplishments and devoted services to the Dharma, the teachings would not be still available today. Therefore, we should remember their grace and always hold them in reverence.

To a practitioner who is fortunate enough to have received the blessings of a lineage, the meaning of lineage becomes his devotion, with all his heart and soul, to carry on, to preserve and transmit the teachings for all generations (of disciples, the real beneficiaries,) to come.

B. The Wisdom of Recognition and Transformation

Self-clinging is the fundamental hindrance to Enlightenment and the fundamental cause of transmigration in samsara. Although it is the main obstacle for a Buddhist practitioner to eradicate, its subtle nature and elusive ways are beyond easy comprehension. Even the

very attempt to attack or reduce self-clinging might very well be indeed an expression of egocentrism, if the motive is limited to self-interest. Facing the dilemma of an invisible enemy who is possibly lurking behind one’s every move, it amounts to an almost impossible task! Thanks

to the wisdom insight of Machig Labdron, the root of self-clinging has been singled out to be the body. Once this is made clear, and the body being a concrete object, the remaining task is much simpler, though not easier.

According to the wisdom insight of Machig Labdron, the real demons are everything that hinders the attainment of liberation. Keeping this wisdom insight in mind, on one hand, all judgments based on personal preferences and interests should be given up,

and on the other hand, all obstacles and adversaries could be transformed by one’s efforts into helping hands on the path toward liberation. For example, a gain could be a hindrance to liberation if one is attached to it, while an injury could be a help to liberation if one uses it to practice tolerance, forgiveness and compassion.

Applying this wisdom insight to the root of self-clinging, the body, Machig Labdron formulated the visualization of Chod, and thereby transformed the root of hindrance into the tool for attaining compassion and liberation.

C. Impermanence and Complete Renunciation

The body is the very foundation of our physical existence. Even after it has been recognized to be the root of self-clinging, it is still very difficult to see how to treat it to bring about spiritual transcendence and liberation. Destroying the body would certainly

end the possibility of further spiritual advancement in this life but not necessarily the self-clinging. The fact that beings are transmigrating from life to life attests to this. Ascetic practices may temporarily check the grip of physical desires over

spiritual clarity and purity, but transcendence depending on physical abuse can hardly be accepted as genuine liberation. The Buddha had clearly taught that the right path is the middle one away from the extremes of asceticism and hedonism.

A fundamental and common approach of Buddhist teachings is to remind everyone of the fact of Impermanence. All things are in constant changes, even though some changes are not readily recognizable. The change from being alive to dead could occur at any moment and could happen in just an instant. Keeping impermanence in mind, one can clearly see that all our attachments to the body are based primarily on wishful

thinking. To be ready for and able to transcend the events of life and death one needs to see in advance that all worldly possessions, including the body, will be lost sooner or later. Hence, a determination to renounce all worldly possessions is the first step toward

spiritual awakening and liberation. Chod as a Buddhist practice is also based on such awareness of impermanence and complete renunciation. In fact, many Chodpas adopt not just the ritual practice but also a way of life that exemplifies such awakening. Many

Chodpas are devout beggars or wondering yogis who stay only in cemeteries or desolate places and do not stay in one place for more than seven consecutive days.

The offering of the body through visualization in a Chod ritual is an ingenious way to counter our usual attitude toward the body; instead of possession, attachment, and tender, loving care, the ritual offers new perspectives as to what could happen to the body as a physical object and thereby reduces the practitioners’ fixation with the body, enlarge their perspectives, and help them to

appreciate the position of the body on the cosmic scale. Chodpas would fully realize that the body is also impermanent, become free from attachment to it, and ready to renounce it when the time comes. When one is ready to renounce even the body, the rest of

the worldly possessions and affairs are no longer of vital concern, only then can one make steadfast advancement on the quest for Enlightenment.

D. Bodhicitta

Machig Labdron emphasizes that the offering of the body in Chod practice is an act of great compassion for all beings, especially toward the practitioner’s creditors and enemies. Great compassion knows no partiality, hence the distinction of friends and foes, or relatives and

strangers does not apply. Great compassion transcends all attachments to the self, hence all one’s possessions, including the body, may be offered to benefit others. In every act of visualized offering of the bodily parts, the practitioner is converting an unquestioned

attachment into an awaken determination to sacrifice the self for the benefit of all. In short, this is the ultimate exercise in contemplating complete self-sacrifice for achieving an altruistic goal.

Chod is a practice that kills two birds with one stone. On one hand, the attachment to the body and self would be reduced through the visualized activity of dismemberment; on the other hand, the visualized practice of satisfying all beings, especially one’s creditors and

enemies, through the ultimate and complete sacrifice of one’s body would nurture one’s great compassion. When the attachment is weakened, the wisdom of non-self would gradually reveal itself. Consequently, Chod develops wisdom and compassion simultaneously in one practice; or to put it in another way, Chod is a practice that nurtures the unification of wisdom and compassion.

In Buddhism Bodhicitta refers to the ultimate unification of wisdom and compassion, the Enlightenment, and to the aspiration of achieving it. Therefore, we may say that Chod stems from the Bodhicitta of Machig Labdron, guides practitioners who are with Bodhicitta through the enactment of Bodhicitta, and would mature them for the attainment of Bodhicitta.

Only when one is completely devoted to the service of all sentient beings can one gain complete liberation from self-centeredness. Just as a headlong plunge takes a diver off the board, complete devotion to Dharma and complete attainment of liberation happens simultaneously. Only

when considerations involving oneself is eradicated, will an act in the name of the Dharma become indeed an act of Bodhicitta, of Enlightenment. Developing Bodhicitta in place of self-centeredness is the effective and indispensable approach to liberation from self, and Chod is the epitome of this approach.

E. Meditation Stability and Visualization

The visualization practice of Chod is not an act of imagination. Were it just imagining things in one’s mind, there is no guarantee that such practice would not drive one insane. To practice Chod properly one should have some attainment of meditation stability so that the

visualizations are focused and not mixed with delusive and scattered thoughts or mental images. Indeed, Chod should be practiced as akin to meditation in action.

To be free from attachments to the body, we have seen above that destroying or abusing it would not do. It is the great ingenuity of Machig Labdron to recognize that attachments being mental tendencies can be properly corrected by mental adjustments. Visualizations

performed by practitioners with meditation stability could have the same or even stronger effects as real occurrences. Furthermore, visualizations can be repeated over and over again to gradually overcome propensities until their extinction.

Using visualization in Chod practices the body remains intact and serves as a good foundation for the practitioner’s advancement on the path to Enlightenment, while the attachment to the body and all attachments stemming from it are being chopped down piece by piece.

Visualizations performed in meditation stability is a valid way of communication with the consciousness of beings who are without corporeal existence. Hence Chod visualizations as performed by adepts are real encounters of the supernatural kind. They

could yield miraculous results such as healing of certain ailments or mental disorders that are caused by ghosts or evil spirits, and exorcism that restores peace to a haunted place.

The five essential ingredients as stated and explained above constitute the key to the formulation of Chod as a Buddhist tantric practice. A thorough understanding of the significance of these essentials is both a prerequisite to and a fruit of successful Chod practices.

3. The Benefits of Chod Practice

Enlightenment is of course the ultimate goal of Chod practice. Machig Labdron revealed her vast spiritual experiences by indicating signs of various stages of realization in Chod. These teachings are still well preserved in Chod traditions. Through the References listed at the end of this work serious readers may find some of these teachings.

In addition to the fruits of realization as indicated above and the application of spiritual power to healing and exorcism as mentioned earlier, there are other benefits that may be derived from Chod practice. Chod practice can help booster the courage and determination to devote one’s whole being to practice, beyond considerations of physical well-being and life, thereby achieving complete

renunciation and significant realization. Chod practice could help total removal of subconscious hindrances that are most difficult to become aware of because these would surface only when challenged by grave situations like dismemberment.

In a dream state I sensed the relaxing effect of Chod; those joints of my body that were tense became relaxed when a curved knife cut through them. The tension in our mind is enhanced by our underlying concept of the body. By removing the mental image of the

body through Chod the tension is reduced. The natural state of one’s body exists before the arising of concepts, and hence, to return to it one needs to transcend the grip of conceptuality.

Many kinds of death are horrible to normal thinking; through practicing Chod it is possible to go beyond attachment to physical existence, and have enough spiritual experiences to understand that whatever the manner of death may be they are just different ways to exit from the physical existence. Such a broad perspective would enable one to remain serene in facing unthinkable tragedies. Such an understanding would make it easier to tolerate, forgive and forgo vengeance.

4. Dispelling Misconceptions about Chod

A fundamental rule of conduct of tantric Buddhism is the proper caring of, though not attachment to, the body. In tantric Buddhism the ritual of Burned Scars of Sila Commitment and the offering of burned fingers are not practiced. Most tantric practices transfer

one’s preoccupation with the body by visualization of the wisdom body of one’s Yidam. In Chod the visualization and identification with the black Vajra Yogini is important, but emphasis is on the visualization of cutting and offering the body. The dismemberment is done in visualization only, hence there is no infringement of the rule of conduct.

In tantric practices the body is usually "meditated away" by returning it in visualization to its empty nature of formlessness. Chod differs from the rest by cutting it away for the compassionate cause of satisfying others’ needs. Chod should not therefore be considered as a practice contrary to the rest. As far as the body is concerned, either approach depends on and makes use of the conditional nature of the body.

The activities visualized in Chod may seem like outbursts of anger, hatred or other negative mentalities or barbaric drives. Indeed the dismemberment visualized in Chod is not intended as a redirection or outlet for any negative impulse or drive. Nor would it result in habitual actions that are negative or barbaric because the visualizations are clearly understood to be born of compassion and there is no bodily

enactment that imitate the visualizations. To a Chodpa these visualized activities represent determinations to destroy the illusion of a permanent body which exists in concepts only. In the motivation of Chod there is not even the faintest trace

of a wanton disregard for life and the body. The coolness to see and use the body as an object without reference to self is a display of wisdom, while the intention to satisfy all others’ needs is born of great compassion. We should not commit the fallacy of deducing

intention from behavior because similar behaviors may originate from diverse motives. Nor should we be confined by considerations involving appearances into submission to the tyranny of taboos; the liberation of employing whatever means that seems appropriate is a true mark of wisdom.

The dismemberment visualizations of Chod are opposite to morbid obsession with cruelty, sadism, self-mortification, masochism and suicidal mania. Obsession with cruelty, sadism, self-mortification, masochism and suicidal mania

are results of self-centeredness or its consequential inability to appreciate the vast openness of the world and what life could offer for the better. Chod works directly toward the reduction of self-centeredness. Chod and the rest may appear to have similar elements, but they are squarely opposite in motivation, mentality during practice, and the consequential results.

The dismemberment visualizations would seem gruesome from an ordinary point of view; however, from the point of view of things as they are and life as it is, there is nothing frightful in what could have happened, nor in what had happened. It is very important to appreciate the openness of mind that Chod visualizations may lead to. In this respect Chod may be compared to inoculation.

The black Wisdom Yogini is a manifestation of the wisdom of selflessness. Her appearance may seem peculiar to people who have not been initiated into her secret teachings, but the reader should be assured that every aspect of her appearance signifies a certain aspect of the wisdom and compassion of Enlightenment. This remark is to dispel shallow mislabeling of Chod as a kind of demonic worship.

Actually none of the misunderstandings discussed above would occur to a Buddhist practitioner who has undergone the preliminary practices and possesses a proper understanding of the philosophy and significance of Chod. However, such misunderstandings would readily occur to most people who happens to come across Chod rituals. Therefore, I think it advantageous to bring them out for discussion so that they would be put to rest once for all.

Chod is an antidote to grasping of the body and the self, but not a method to increase antagonism. The basic spirit of Chod is not to destroy, conquer or become an enemy of creditors, evil spirits, etc. Its essence is self-sacrifice out of compassion and wisdom.

Chod is an antidotal practice; a Chodpa should not thereby become over concerned with the body in the opposite direction, e. g., feeling aversion toward the body. The ideal result should be freedom from preoccupation with the body and the self.

Chod is an extreme practice. It is not the only path toward liberation from self, but it is a valid path toward liberation. Without such understanding one’s knowledge of what it means to be liberated from the self is incomplete and possibly erroneous.

Source

By Dr. Yutang Lin

yogichen.org