The Buddhist mandala cosmos

As soon as we have gained some insight into the cosmography of Buddhism it becomes apparent how fundamentally different it is from our modern scientific world view. It is primarily based upon the descriptions of the Abhidharmakosa, a written record from the Mahayana scholar Vasubhandu (fifth century C.E.). The Kalachakra Tantra has largely adopted Vasubhandu’s design and only deviates from it at particular points.

At the midpoint of the Buddhist universe rises Meru, the world mountain, which towers above everything else and on which heaven and earth meet. It is round like the “axle of a wheel”. In a passage in the Kalachakra Tantra it is compared to the vajra and described as a gigantic “thunderbolt” (Newman, 1987, p. 503). The Swiss mandala expert, Martin Brauen, sees in it a “dagger-like shape” and therefore calls it the “earth dagger” (Brauen, 1992, p. 127). According to Winfried Petri the world mountain has the form of the “inverted base of a cone”. All of these are phallic metaphors.

Five circles of different sizes surround the gigantic “phallus” like wheels; they are each assigned to an element. Starting from the outermost they are the circle of space, the circle of air, the circle of fire, the circle of water, the circle of earth. Air and fire, however, permeate the entire cosmic architecture. “In all directions are wind (air) and fire”, the Kalachakra Tantra says (Newman, 1987, p. 506). These two elements are the spirit, so to speak, which blows through the entire construction, but they also

form the two forces of destruction which shall obliterate the world structure at the end of time, exactly as the breath (air, wind) and the flames (fire, candali) together burn down the old bodily aggregates in the yogi’s mystic body. The circle of the earth consists of a total of twelve individual continents which swim on the circle of water like lotus blossoms. It thus forms a discontinuous, non-homogenous circular segment. One of these continents is our world, the “earth”. It bears the name Jambudvipa, which means “rose apple tree continent”.

In Vasubandhu’s original account, Meru is not surrounded by the five elements, but rather by seven ring-like chains of mountains, which lie like wheels around the world axis. Huge oceans are found between these wheels. The last of these seas is also the largest. It is called Mahasa Mudra, the Great Mudra.

Thus, in the Buddhist concept of the world Meru forms the vertical, which is divided into three segments — from bottom to top: (1) hell, (2) earth, and (3) heaven.

At its roots, (1), the seven main hells are found, each more horrific than the last. In contrast to Western beliefs about the under world, in Buddhism there are “cold hells” in addition to the hot, where souls are tormented not with fire but with ice. Watery hells can also be found there, in others only smoke. The precise description of the torments in these dreadful places has been a favorite pastime of Tibetan monks for centuries. Above the underworld, at the foot of Meru, live the so-called hunger spirits (pretas),a restless horde of humanoid beings, who are driven by constant desire.

In the middle segment of the mountain, (2), we encounter the twelve continents, and among them Jambudvipa, the earth. Since the continents are surrounded by ocean, there is no natural land bridge to the world axis. We humans live on the “rose apple tree continent” (Jambudvipa). This continent is also called the “land of karma”, since the beings who live there are still burdened with karma (stains as a consequence of bad deeds). But we inhabitants of Jambpudvipa have the chance to work off such karmic stains for good, by following the teachings of the Buddha. This is a great privilege which is not as readily available to the inhabitants of other spheres or the other continents.

Above the earthly world rises the segment of the heavens, (3), and here we find ourselves in the realm of the stars and planets. Beyond this one can wander through various divine circles, which become ever more powerful the higher one goes. The “divine” ascent begins in regions inhabited by deities who have not yet freed themselves from their desires. Then we enter the victorious residences of the thirty-three deities of the “realm of forms”, which we can regard as “Forms” in the platonic sense, that is, as immobile, downward radiating energy fields. Among them are to be included, just as with Plato, the higher entities which represent the pure essence of the five elements.

We now leave behind Mount Meru as a geographically describable region and “fly” through a “zone of intersection”, in which the realm of the form gods and the even more powerful, more grandiose, and more holy imperium of formlessness can be found. The “inhabitants” of this sphere are no longer personalities at all and cannot be visualized, rather, they bear the names of general terms. The Abhidharmakosa calls them “Without sorrow”, “Nothing greater”, “Great success”, Stainless”, and so forth. Even higher up we encounter a sphere, which has names such as “Infinite consciousness “ and “ Nothing whatever” (Tayé, 1995, p.155). The Kalachakra Tantra has completely incorporated this model of the world from Mahayana Buddhism.

From this staged symbolism of the world mountain we can easily recognize that it embodies not just a cosmic model, but also, homologously, the likeness of an initiatory way. Now whether this way begins down in hell or from the middle of the continent of earth, it should in any case lead, via a progression through various earthly and heavenly spheres, to the highest regions of the formless realm.

The cosmos and the energy body of the yogi

As we have already indicated a number of times, a homology exists between the Buddhist cosmogram and the bodily geography of the yogi. Microcosm and macrocosm are congruent, the world and the mystic body of a practicing yogi form a unity. The ADI BUDDHA, as the perfected form of the highest tantra master, and the cosmos are identical.

"Everything is in the body” — this famous occult correspondence is of fundamental significance for Tantrism too. The parallel to the world axis (Meru) is formed, for example, by the middle channel (avadhuti) in the mystic body of the yogi. The texts then also refer to it simply and straightforwardly as “Meru”. Just as the realm of formlessness is to be sought above Mount Meru in the cosmos, so the yogi (ADI BUDDHA) experiences the highest bliss of the “emptiness of all forms” above his head in the “thousand-petaled lotus”. The forehead chakra and the throat chakra correspond to the residences of various of the thirty-three form gods (Forms) mentioned above. Humanity lives in the heart of the yogi and below this it goes on to the genitals, where the realms of hell are situated.

Correspondingly, it says in the Kalachakra Tantra: “Earth, wind, gods, seas, everything is to be recognized amidst the body” (Grünwedel, Kalacakra II, p. 2). All the parts of the “small” body correspond to the parts of the “great” body: The yogi’s (ADI BUDDHA’s) rows of teeth form the various lunar houses; the veins the rivers. Hands and feet are islands and mountains, even a female louse hidden in the pubic hair of a Tantric has a “transcendent” significance: It counts as the dangerous vulva of a demoness from a particular region in hell (Grünwedel, Kalacakra II, p. 34). This bodily homology of the cosmos is the

great secret which Buddha revealed to King Suchandra as he instructed him in the Kalachakra Tantra: “As it is without, so it is in the body.” (Newman, 1987, pp. 115,104, 472, 473, 504, 509). At the same time as the secret was exposed, the “simple” recipe with which the yogi could attain and exercise absolute control over the whole universe was also revealed: in that he controls the energy currents within his mystic body he controls the cosmos; on the scale in which he lets bliss flow through his veins (wind channels), on that scale he brings delight to the universe; the turbulence which he calls forth in his insides also shakes the external world through storms and earthquakes. Everything happens in parallel: when the yogi burns up his body during the purification the very same procedure reduces the whole universe to rubble and ash.

Chakravala or the iron wheel

Just as the androgynous body of the ADI BUDDHA or of the enlightened yogi concentrates within itself the energies of both sexes, so Buddhist cosmography is also based upon a gender polarity. Meru, the world mountain, has a most obviously phallic character and is therefore also referred to as Vajra or, more directly, as Lingam (phallus). The great oceans which surround the masculine symbol represent — as a circle and as water — the feminine principle.

Oddly, the outermost chain of mountains within the cosmic model are forged from pure iron. This iron crown must have a deep symbolic significance since the whole system is named after it; its name is Chakravala ("iron wheel”). We thus have to ask ourselves why the Buddhist universe is framed by a metal which is seen all over the world as a symbol of injury, killing,

and war. The image naturally invites a comparison to the “iron age” to which in Greco-Roman mythology humanity is chained before its cyclical downfall. The Indian idea of the Kali yuga and the European one of the “iron age” are congruent in a surprising number of aspects. In both cases it comes to an increasingly rapid degeneration of the law, cusstoms, and morality. In the end only a war of all against all remains. Then a savior figure appears and the whole cosmic game begins afresh.

Modern and Buddhist world views

The reader may have already asked him or herself how contemporary Tibetan lamas reconcile their traditional Buddhist cosmology with our scientific world view. Do they reject it outright, have they adopted it, or do they seek for a way to combine both systems? Someone who knew the Kalachakra Tantra well, the Kagyupa guru, Kalu Rinpoche, who died in 1989, gave a clear and concise answer to all three questions: “Each of these cosmologies is perfect for the being whose karmic projections cause them to experience their universe in this manner. ... Therefore on a relative level every cosmology is valid. At a final level, no cosmology is

absolutely true. It cannot be universally valid as long as there are beings in fundamentally different situations” (Brauen, 1992, p. 109). According to his, the cosmos is an apparition of the spirit. The world has no existence outside of the consciousness which perceives it. If this consciousness changes then the world changes to the same degree. For this reason the cosmography of Buddhism does not describe nature but solely forms of the spirit. Such an extreme idealism and radical relativism helps itself to the power to undermine with a single dry statement the foundations of our scientific world view. But if nothing is final any more, it follows that everything is possible, even the cosmology of the Abhidharmakosa. Yet, the lamas argue, only at the point in time where all of humanity have adopted the Buddhist paradigm can they also perceive the gigantic Meru mountain in the middle of their universe. Today, Tibetan gurus claim, only the few “chosen” have this ability.

In the second part of our study, we shall examine the intensive and warm relationship between the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and modern Western scientists and show that the radical relativism of a Kalu Rinpoche is also distributed in such circles. Similar philosophical speculations by Europeans can be found, even from earlier times. Heinrich Harrer, who traveled extensively through Tibet tells in an anecdote of how Westerners readily — even if purely out of coquetry — take on the Tibetan world view. Harrer was

assigned to impart to the Tibetans, but in particular the young Dalai Lama, the modern scientific world view. In the year 1948, as he tried to explain to a group of Tibetan nobles at a party that our earth is round and is neither flat nor a continent, he called upon the famous Italian Tibetologist, Giuseppe Tucci, who was also present, to be his witness and support his theory. “To my greatest surprise”, says Harrer, “he took the side of the doubters, since he believed that all sciences must constantly revise their theories and one day the Tibetan teaching could just as well prove to be right” (Harrer, 1984, p. 190).

Thus, following a Buddhization of our world there would be no need for the “converted” population of the world to do without the traditional cosmic “map” of the Abhidharmakosa, since in accordance with the Buddhist theory of perception the “map” and the territory it describes are identical. Both, the geography and its likeness in consciousness, ultimately prove themselves to be projections of one and the same spirit.

The downfall of the tantric universe

The mystic bodily structure of the yogi (ADI BUDDHA) duplicates the cosmogram of the Chakravala. Correspondingly, the fate of his energy body proves to be identical to the fate of the universe. Just as the fore woman in the form of the candali burns up all the coarse elements inside the tantra master step by step, so at the end of time the whole universe becomes the victim of a world fire, which finds its origin at the roots of Mount Meru in the form of Kalagni. Step by step, Kalagni

set the individual segments of the world axis aflame and arises flickering up to the region of the form gods (the Forms). Only in the highest heights, in the sphere of formlessness, does the destructive fire come to a standstill. When there is nothing more to burn the flame is extinguished from alone. That which remains of the whole of Chakravala are atomic elements of space ("galactic seeds”), which provide the building blocks for the construction of a new cosmos, and which, in accordance with the law of eternal recurrence, will look exactly the same as the old one and share the same fate as its predecessor.

The mandala principle

The Buddhist universe (Chakravala) takes the form of a mandala. This Sanskrit word originally meant ‘circle’ and is translated into Tibetan as kyl-khor, which means, roughly ‘center and periphery’. At the midpoint of the Chakravala we find Mount Meru; the periphery is formed by the gigantic iron wheel we have already mentioned.

There are round mandalas, square mandalas, two- and three-dimensional mandalas, yet in all cases the principle of midpoint and periphery is maintained. The four sides of a square diagram are often equated with the four points of the compass. A five-way concept is also characteristic for the tantric mandala form — with a center and the four points of the compass. The whole construction is seen as an energy field, from which, as from a platonic Form, tremendous forces can flow out.

A mandala is considered to be the archetype of order. They stand opposed to disorder, anarchy and chaos as contrary principles. Climatic turbulence, bodily sicknesses, desolate and wild stretches of land, barbaric peoples and realms of unbelief all belong to the world of chaos. In order to seize possession of such regions of disorder and ethnic groupings or to put an end to

chaotic disturbances (in the body of a sick person for instance), Tibetan lamas perform various rites, which ultimately all lead to the construction of a mandala. This is imposed upon a “chaotic” territory through symbolic actions so as to occupy it; it is mentally projected into the infirm body of a patient so as to dispel his or her illness and the risk of death; it is “pulled over” a zone of protection as a solid fortification against storm and hail.

Like a stencil, a mandala pattern impresses itself upon all levels of being and consciousness. A body, a temple, a palace, a town, or a continent can thus as much have the form of a mandala as a thought, an imagining, a political structure. In this view, the entire geography of a country with its mountains, seas, rivers, towns and shrines possesses an extraterrestrial archetype, a mandala-like prototype, whose earthly likeness it embodies. This transcendent geometry is not visible to an ordinary eye and conceals itself on a higher cosmic level.

Hidden behind the geographical form we perceive, the country of Tibet also has, the lamas believe, a mandala structure, with the capital Lhasa as its center and the surrounding mountain ranges as its periphery. Likewise, the street plan of Lhasa is seen as the impression of a mandala, with the holiest temple in Tibet, the Jokhang, as its midpoint. The architectural design of the latter was similarly based on a mandala with the main altar as its center.

The political structure of former Tibet also bore a mandala character. In it the Dalai Lama formed the central sun (the mandala center) about which the other abbots of Tibet orbit as planets. Up until 1959 the Tibetan government was conceived of as a diagram with a center and four sections (sides). “The government is founded upon four divisions”, wrote the

Seventh Dalai Lama in a state political directive, “These are (1) the court of law, (2) the tax office, (3) the treasury, and (4) the cabinet. They are all aligned to the four points of the compass along the sides of a square which encloses the central figure of the Buddha” (Redwood French, 1985, p. 87).

The prototype of the highest Buddha and the emanations surrounding him was thus transferred to the state leadership and the various offices which were subordinate to it. Of course, the central figure of this political mandala is intended to be the Dalai Lama, since he concentrates the entire worldly and spiritual power in his person. Every single monastery reiterates this political geometry with the respective abbot in the middle.

But the mandala does not just structure the world of appearances; in Buddhist culture it likewise determines the human psyche, the spirit and all the transcendental spheres. It serves as an aid to meditation and as an imaginary palace of the gods in the tantric exercises. On a microcosmic level the energy body of the yogi is seen as the

construction of a three-dimensional mandala with the middle channel (avadhuti) as the central axis. The whole cosmic-psychic anatomy of the ADI BUDDHA (tantra master) is thus a universal mandala. For this reason we can comprehend Buddhist culture in general (not just the Tibetan variant) as a complicated network of countless mandalas. Further, since these exist at different levels of being, they are encapsulated within one another, include one another, and overlap each other.

Quite rightly one aspect of the Buddhist/tantric mandalas has been compared in cross-cultural studies with the magic circles used by the medieval sorcerers of Europe to summon up spirits, angels, and demons. Then a mandala ("magic circle”) can also be used to conjure up Buddhas, gods and asuras (demons).

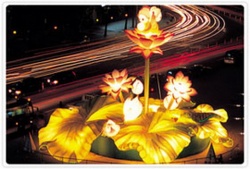

The Kalachakra sand mandala

Mandalas are employed in all tantric rituals, yet in the Kalachakra Tantra it plays an extremely prominent role. Before the seven lower solemnities of the Time Tantra even begin a mandala –a very lavish one indeed — is constructed in the visible external world. Specially trained monks — for the Dalai Lama a special unit from the Namgyal institute — are entrusted with its construction. The “building

materials” consist primarily of colored sand, lines and figures of which are applied to a sketch in a complicated process lasting several days. Every line, every geometric form, every shading, every object inserted has its cosmic significance. Since the mandala is built from sand, we are dealing with a very vulnerable work of art, which can easily be destroyed; and this, astonishingly — and as we shall see — is the final goal of the entire complicated procedure.

The sand mandala of the Time Tantras can be deciphered as the visual representation of the whole Kalachakra ritual by anyone who understands the symbols depicted there. Such an interpreter would once again come across all the semantic content we have encountered in the above description of the tantric initiatory way.

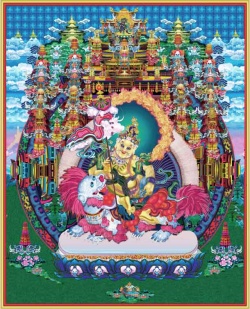

For this reason, we must regard this external image in sand as just the visible reflection of an inner-spiritual construction which (in another sphere) the yogi imagines as a magnificent palace built upon the peak of Mount Meru. [1] As the center and the two regents of the imagined temple palace we encounter Kalachakra and his wisdom consort, Vishvamata. They are enthroned as the divine couple in the midpoint of the holy of holies.

This Buddhist “Versailles” is inhabited by a total of 722 deities, the majority of whom represent the individual segments of time: the gods of the twelve-year cycles, the four seasons, twelve months, 360 days, twelve hours, and sixty minutes all dwell here. In addition there are the supernatural entities who represent the five elements, the planets, the 28 phases of the moon and the twelve sensory regions. Very near to the center, i.e., to the divine couple Kalachakra and Vishvamata, the four meditation Buddhas can be found in union with their partners, then follow a number of Bodhisattvas.

The architecture of the Kalachakra palace encompasses five individual mandalas, each enclosing the next. Segments which lie closer to the center (the divine couple) are accorded a higher spiritual evaluation than those which are further away. The fivefold organization of the building complex is supposed to reflect, among other things, the five rings (the five elements) which lie around Mount Meru in Buddhist cosmography. Likewise the height and breadth of the palace are in their relation to one another a copy of the proportions of the cosmos. Thus the Kalachakra mandala is also a microcosmic likeness of the Buddhist universe.

Anyone entering the Kalachakra palace from outside progresses through a five-stage initiation which culminates in the inner sanctum where the primordial couple, Kalachakra and Vishvamata, are in union. But seen from within, each of the individual mandala segments and the deities dwelling within them represents an outward radiation (emanation) of the divine first couple.

Just as the macrocosmic mandala of the universe with Mount Meru as its axis can be rediscovered in the microcosmic body of the yogi (ADI BUDDHA), so too the Kalachakra palace is identical with his mystic body. We must never lose sight of this. For this reason, the detailed description of the Kalachakra sand mandala which now follows must also be regarded as the anatomy of the

tantra master (ADI BUDDHA). The anatomical “map” of the ADI BUDDHA thus exhibits a number of different images: on one occasion it possesses the structure which corresponds to that of the entire universe, on another it forms that of the Kalachakra palace, or it corresponds to the complicated construction of the dasakaro vasi ("the Power of Ten”) described above. But in all of these models the basic mandala-like pattern of a center and a periphery is always the same.

The structure of the Kalachakra palace

The primordial divine couple, the time god Kalachakra and the time goddess Vishvamata, govern from the center of the Kalachakra palace. They are depicted in the visible world of the sand mandala by a blue vajra (Kalachakra) and an orange dot

(Vishvamata). Directly beneath them a yellow layer of sand which represents Kalagni, the destructive fire, is found; beneath this there is a blue layer, symbol of the apocalyptic planet, Rahu. Layers for the sun, the moon, and for a lotus flower follow. The destruction of the primordial couple is thus, through the presence of Kalagni and Rahu, already preprogrammed in the center of the sand mandala, or rather of the palace of time.

Kalachakra and Vishvamata are surrounded by eight lotus petals (all of this is made from colored sand). Now these do not — as one might assume — represent eight further emanation couples, but rather– in the official interpretation — we encounter the eight shaktis here. We are thus dealing with eight female beings, eight energy bearers (or eight “sacrificial goddesses”). They correspond to the eight karma mudras who surround the tantra master in union with his partner in the ganachakra, the twelfth level of initiation (the vase initiation). However, when we think back, there was talk of ten Shaktis before. We reach the number “ten” by counting two feminine aspects of Vishvamata (the central goddess) in addition to the eight “sacrificial goddesses” (lotus petals). Together they signalize the ten chief winds (the dasakaro vasi) with which the tantra master controls all the microcosmic energies in his mystic body.

Thus, within the innermost segment of the palace of time the whole tantric sacrificial scenario is sketched out using only a very few symbols, since the ten shaktis (originally ten women) are, as we have described in detail above, manipulated and eradicated as autonomous individuals in the ganachakra ritual so that their feminine energies can be transferred to the tantra master. This central segment of the sand mandala bears the name of the “mandala of great bliss” (Brauen, 1992, p. 133).

The second, adjacent complex is called the “mandala of enlightened wisdom”. Here there are sixteen pillars which symbolize different kinds of emptiness and which divide the space into sixteen different rooms. The latter are occupied by couples who are in fact peaceful deities. They are represented in the mandala by small piles of colored sand. In this part of the palace ten (!) vases (kalashas) can also be found. These are filled with revolting substances like excrement, urine, blood, human flesh, and so on, which are transformed into bliss-conferring nectars during the ritual by the tantra master. These vessels symbolize once again the ten “sacrificial goddesses” or the ten mudras of the ganachakra. In the first precise description of a Kalachakra ritual by a Western academic (Ferdinand Lessing), reference is made to the feminine symbolic significance of the vases: the “lamas ... proceed to the podium, each with a large water pot (kalasha). They move it to and fro. It symbolizes the young lady of the initiation, who plays such a great role in this cult” (Wayman, 1973, p. 62). Yet again, the kalashas correspond to the ten winds or the “Power of Ten” (dasakaro vasi) and thereby to the diamond body of the ADI BUDDHA.

On our tour of the palace of time, the third segment with the name of “the mandala of enlightened mind” follows. This is the house of the Bodhisattvas and Buddhas. The latter, the Dhyani or meditation Buddhas, reside here in close embrace with their consorts: to the East, the black Amoghasiddhi with Locana; to the South, the red Ratnasambhava with Mamaki; to the North, the white Amitabha with Pandara; to the West, Vairocana in the arms of Tara. The areas between the points of the compass are likewise occupied by Buddha couples. All the Bodhisattvas who dwell the in the “mandala of enlightened mind” are also portrayed in the yab-yum posture (of sexual union). This third segment demonstrates most vividly that Tantrism derives the emanation of time from the erotic love of divine couples.

The fourth “mandala of enlightened speech” follows. Within it are found eight lotus flowers, each of which itself has eight petals. Once again the pattern of the ganachakra, which we have already encountered in the center of the sand mandala, is repeated in this bouquet. In the middle of each of the eight lotuses a couple sits in close embrace and on each of the eight surrounding petals we can discern a goddess. This makes a total of eighty deities (64 shaktis, 8 female partners, and 8 male deities).

The large number of shaktis, “daughters” of the mudras “sacrificed” in the ganachakra, is an indicator of how fundamentally the idea of the tantric female sacrifice determines the doctrine of time and its artistic representation. At the gates which lead out from the fourth segment into the third “mandala of enlightened mind”, we are once again confronted with the symbolic representation of “sacrificial goddesses”. Aside from this, 36 further shaktis, who represent the root syllables of the Sanskrit alphabet and thereby the building blocks of language, live in this building complex.

As the final and outermost segment of the mandala palace we enter the “body mandala”. There we meet the 360 deities of the days of the year. Here too we encounter the basic pattern of the ganachakra. There are twelve large lotuses, each with 28 petals. In the center of each flower a god and a goddess embrace one another, all around them sit 28 goddesses grouped into three rows. Each lotus thus exhibits 30 deities, multiplying by twelve we have the 360 day gods (five days are not calculated). In addition we meet in the body mandala twelve pairs of wrathful deities and 36 goddesses of desire.

We have nonetheless not yet described all the grounds of the palace. The five square architectural units already mentioned are namely bordered by six circular segments. Numerous symbols of bliss like wheels, wish-granting jewels, shells, mirrors, and so on, rest in the arcs (quadrants) which are formed between the last square and the first circle. The five subsequent circles symbolize the elements in the following order: earth, water, fire, wind, and space. Cemeteries are to be found on circles three and four, depicted in the form of wheels. In the imagination they are inhabited by ten horrifying dakinis with their partners. From a Buddhist point of view this “ring of the dead” signifies that only he who has surmounted his bodily existence may enter the mandala palace.

The fifth circle of space is represented by a chain of golden vajras. The whole mandala is surrounded by a circle of flames as a sixth ring. According to a number of commentator this is supposed to represent the wisdom of Buddha; however, if we further pursue the fate of the sand mandala, it must be associated with the “world fire” (Kalagni) which in the end burns down the palace of the time gods.

As aesthetic and peaceful as the sand mandala may appear to be to a Western observer, it still conceals behind it the frozen ornament of the sacrificial ritual of Tantrism. Every single female figure which inhabits the palace of time, be she a dakini, shakti, or a “sacrificial goddess”, is the bearer of the so sought after “gynergy” which the yogi has appropriated through his sexual magic practices so as to then let it flow as the power source of his androgynous mystic body. The Kalachakra palace is thus an alchemic laboratory for the appropriation of life energies. In the ritual fate of the sand mandala we shall unmistakably demonstrate that it is a gigantic sacrificial altar. It is not just the shaktis who are sacrificed, but the erotic couples as well, who delight the temple with their untroubled pleasures of love, indeed the time god (Kalachakra) and the time goddess (Vishvamata) themselves. The downfall of them all is preordained, their fate is sealed.

The construction of the Kalachakra sand mandala

The construction of the Kalachakra sand mandala is a complex and multilayered procedure which is carried out by a number of specially trained lamas. The “master builder “ of the diagram and the spiritual leader of the Kalachakra initiation need not always be the same person. They are so to speak the assistants of the tantra master. Nonetheless, at the outset the latter makes the following appeal to the

time god: “Oh, victorious Kalachakra, lord of knowledge, I prostrate myself to the protector and possessor of compassion. I am making a mandala here out of love and compassion for my disciples and as an offering in respect to you. Oh Kalachakra, please be kind and remain close to me. I, the vajra master, am creating this mandala to purify the obstructions of all beings. Therefore, always be considerate of my disciples and me, and please reside in the mandala” (quoted by Bryant, 1992, p. 141).

The grounds sought out for the ritual are now subjected to a rigorous examination, the so-called “purifying of the site”. Monks investigate the ground, measurements are taken, mantras and sutras are quoted. Subsequently it comes to a highly provocative scene, in which the local spirits and the earth goddess are violently forced to agree to the construction of the mandala.

For this purpose one of the lamas takes on the appearance of Vajravega, that is, he visualizes himself as this deity. Vajravega is blue in color, has three necks and 24 hands. As clothing he wears a tigerskin skirt, decorated with snakes and bones. He is considered to be the terrifying emanation of the time god Kalachakra. He can evoke sixty wrathful protective deities from out of his inscrutable heart, who then storm out through his ears, nostrils, eyes, mouth, urethra, anus, and from an opening in the top of his skull. Among these are found zombies, vampires and dakinis with the heads of animals.

In the imaginations of the lamas who conduct the ritual, this monster now drags in the impeding local spirits with iron hooks and, once they have been bound in chains, nails them down in the ten directions with ritual daggers. A further ten wrathful deities are projected into each of these daggers (phurbas). There are indications which must be regarded seriously that in the performance of the Kalachakra rituals it is not just the local spirits, but likewise the earth mother (Srinmo) who embody the nailed down victims. This myth of the nailing of Srinmo played a central “national” role in the construction of Tibetan temples, which actually represent nothing more than three-dimensional mandalas. We shall come to speak of this in detail in the second part of our study.

Now the tantra master solemnly circles the mandala location in a clockwise direction, and sprinkles it with various substances and holy water. After this the monks who participate in the ritual imagine in their spirits that this location is covered in numerous small vajras.

Afterwards there is a significant demonstration of power: The tantra master sits down on his own in the center of the mandala space, faces the East and says the following: “I shall build on this place a mandala in the manner in which I have imagined it” (quoted by Brauen, 1992, p. 77). With this act of occupation he makes it unmistakably clear who the lord of the ritual action is. Further liturgical actions follow.

The tantra master evokes the terrifying deity, Vajravega, anew, and once again drives potential disruptive spirits out of the mandala grounds. He is so filled with wrathful deities that horror figures who are supposed to protect the mandala even emanate from out of the soles of his feet. Afterwards the place is occupied by the symbols of the five Dhyani Buddhas. On the table top, the lama lays a lotus, a sword, a wish-granting jewel, a wheel and, in the middle, a vajra. This centrally placed “thunderbolt” demonstrates yet again the masculine control of the earth.

This dominating, patriarchal behavior has not always been present in the history of Buddhism. In a famous scene from the life of the historical Buddha, he calls upon the earth to bear witness to his enlightenment by touching it with his right hand (Bhumisparsha mudra). Tantric Buddhism has preserved this scene among its Buddha legends, but has added a small change; here Shakyamuni makes the gesture of stroking the earth with a vajra, the scepter of phallic power. “This instrument is indispensable for the liturgy of the Great Path”, Giuseppe Tucci writes, “The earth transformed by the vajra becomes diamond” (Tucci, 1982, p. 9

7). As spiritually valuable a symbol as the diamond may appear to be, it is not just an image of purity but is also a metaphor for sterility. Between the vajra and the earth lies the opposition between spirit and life, or — as the American Buddhist Ken Wilber would express it — the “noosphere” (the realm of the spirit) and the “biosphere” (the realm of nature). In that the earth is transformed into a diamond by the tantric gesture of the Buddha, nature is symbolically transformed into pure spirit and woman into a man.

But let us return to the script which describes the construction of the sand mandala. After the fixation of the earth spirits or the earth mother, the “procession of the ten vases” which are filled with nectars follows. These are carried by monks around the ritual table upon which the sand mandala will be built. Yet again the number ten! The ten vases, the ten powers, the ten winds, the ten shaktis — they are all variations on the ten mudras, who participated and were “sacrificed” in the highest initiation of the ganachakra ritual.

All their energies flow into Vishvamata, the chief consort of the Kalachakra deity. The time goddess is symbolized by a seashell which the monks lay in the middle of the ritual table and which is to be filled with the essences from all ten vessels (vases). Here the shell represents the feminine element at its highest concentration.

The tantra master now ties a golden vajra to a thread. He puts the other end of the thread to his heart and then lays the “thunderbolt” with emphasis on the central shell. The sovereignty of the masculine principle (vajra) over the feminine principle (the shell) could not be demonstrated more unequivocally. Afterwards, all the ritual objects are removed from the mandala.

The time has now come to begin with the preparatory sketches of the sand mandala. The monks commence with the “snapping of the wisdom string”. Here we are dealing with five different threads which symbolize the five Dhyani Buddhas with their consorts. Through a ritual “plucking” of these strings, the texts tell us, the mandala site becomes occupied by these five supreme beings. [2]

After many recitations the monks now begin with the actual artistic work, surrounded by numerous containers filled with the colored sand. This is carefully applied to the preliminary sketch with a type of funnel. This requires extreme precision, since the sand must form hair-thin lines, and there are even a number of drawings of figures to be rendered in sand. Work begins in the middle and proceeds outwards, that is, the center of the mandala is created first and one then works step by step towards the periphery. It takes another five days before the artwork is completed.

At the end, the complete work is surrounded by ten (!) ritual daggers (phurbas) which act as protective symbols. Likewise, ten (!) vases which are supposed to represent the ten shaktis are arranged around the mandala. Since all the tenfold symbols in the Kalachakra Tantra stand in a homologous relation to the “sacrificed” mudras (shaktis, dakinis, yoginis) of the ganachakra ritual described above, the mandala, with- we repeat — its numerous sequences of ten, is an ornamental demonstration of the “tantric female sacrifice” also described above.

Once the vases and daggers have been put in place, the whole artwork is hidden behind a curtain, as if the sacrificial scenario concealed behind the sacred work ought to be masked. To close, the monks perform another dance. Anyone who has up till now doubted whether the Kalachakra sand mandala concerns the visual portrayal of a sacrificial rite, actually ought to be convinced by the name of this dance. It is called the “ritual dance of the sacrificial goddesses”.

The destruction of the mandala

The sand mandala accompanies the seven lower levels of the public Kalachakra ritual as the mute and earthly likeness of a transcendental tantric divine palace. It is supposed to help the initiand create a corresponding architectural work with all its inhabitants within his imagination and to thus give it a spiritual existence. As in the real construction, within the imagination work also begins at the center of the mandala, in which Kalachakra and Vishvamata are united. Starting from there, the initiand visualizes step by step the construction of the whole palace of time with its 722 gods. He thus commences at the inner sanctum, and then imagines every mandala segment which follows, ending with the periphery of the ring of flame, which blazes around the entire architectural construct.

During the imaginary construction of the mandala, the initiand is suddenly required to imagine an extremely puzzling scene which we would like to examine more closely: “Out of the syllable HUM”, it says in the Kalachakra Tantra, “Vajravega emanates in the heart of the medititator [the initiand], the wrathful form of Kalachakra — grinning and with gnashing teeth Vajravega stands upon a chariot drawn by a fabulous being; he thrusts a hook into the navel of Kalachakra, ties his hands up, threatens him with weapons and drags him before the meditator, in whose heart he finally dissolves himself” (Brauen, 1992, p. 114).

What is happening? Vajravega, the wrathful emanation of the time god, suddenly turns against his own “emanation father”, Kalachakra, and brutally drags him before the meditating adept. In this scene a distinction is thus drawn between Kalachakra and Vajravega. Is this — as Martin Brauen suspects — to be interpreted as the symbolic repetition of the act of birth, which is indeed also associated with pain?

Such an interpretation does not seem convincing to us. It seems far more plausible to recognize a somewhat obscure variant of the dark demon Rahu in the Vajravega figure, who destroys the sun and the moon in the Kalachakra Tantra so as to claim power over time in their stead. Brauen also indirectly concedes this when he compares the aggressive emergence of Vajravega with the activation of the “middle channel” (avadhuti) in the mystic body of the yogi and the associated destruction of both energy streams (the sun and moon). The same procedure is also regarded to be the chief task of Rahu, and likewise, as we have described above, the middle channel bears the name of the dark planet (Rahu). Be that as it may, the destructive arrival of Vajravega heralds the fate of the whole sand mandala and of the palace of time hidden behind it.

During the seven lower solemnities of the Kalachakra Tantra, the mandala artwork is left standing. At the end of the whole performance the tantra master recites a number of prayers and certain mantras. He then circles the sand mandala, removing with his fingers the 722 gods who were scattered across it in the form of seeds and laying them on a tray. At the same time he imagines that they enter his

heart. He thus absorbs all the time energies and transforms them into aspects of his own mystic body. He then grasps a vajra, symbol of his diamond masculinity, and begins to destroy the sandy “divine palace” with it. The whole impressive work dissolves into colorful heaps and is later swept together. The monks tip the colored mixture into a vase. The master sprinkles a little of this in his head, and gives a further mini-portion to his pupils. With prayers and song a procession carries the sandy contents of the vase to a river and surrenders it there to the nagas (snake gods) as a gift.

But an important gesture is still to come. The tantra master returns to the site of the mandala and with water washes off the white basis lines remaining on the site. Then he removes the ten ritual daggers. Facing the East he now seats himself on the cleansed mandala site, vajra and bell in his hands, the absolute lord of both sexes (Kalachakra and Vishvamata), of time and of the universe.

This destruction of the sand mandala is usually seen as an act which is supposed to draw attention to the transience of all being. But this forgets that the palace of time is only destroyed as an external construction and that it continues to exist in the interior of the highest tantra master (as ADI BUDDHA). In his mystic body, Kalachakra and Vishvamata live on as the two polar currents of time, albeit under his absolute control. At the end of the ritual, the yogi (ADI BUDDHA) has transformed himself into a divine palace. Then his microcosmic body has become identical to the Kalachakra palace; we can now rediscover all the symbols which we encountered there as forces within his energy body.

The world ruler: The sociopolitical exercise of power by the ADI Buddha

In his political function the ADI BUDDHA is a world ruler, a “universal sovereign”, a “world king” (dominus mundi), an “emperor of the universe”, a Chakravartin. The early Buddhists still drew a distinction between a Buddha and a Chakravartin. Hence we can read in the legends of Buddhism’s origins how a holy man prophesied to Shakyamuni’s father that his wife, Maya, would soon bear an enlightened one (a Buddha) or a world ruler (Chakravartin), depending upon which this son would as a young man later decide to be. Gautama chose the way of the “spiritual” Buddha and not that of the “worldly” Chakravartin, who in the customs of his time also had to act as military leader alongside his political duties.

In Mahayana Buddhism this distinction between a dominus mundi and an enlightened being increasingly disappears, yet the Chakravartin possesses exclusively peaceful characteristics. All his “conquests”, reports the scholar Vasubandhu (fourth or fifth century C.E.), are nonviolent. The potentates of the world voluntarily and unresistingly subject themselves on the basis of his receptive radiation. They bow down before him and say: “Welcome, O mighty king. Everything belongs to you, O mighty king!” (quoted by Armelin, n.d., p. 21). He is mostly incarnated as an avatar, as the reincarnation of a divine savior, who should lead humanity out of its earthly misery and into paradise.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, especially in the Kalachakra Tantra, the Chakravartin is the successful result of the sexual magic rites we describe above. The “asocial” yogi, who during his initiatory phase hangs around cemeteries and with prostitutes like an outlaw has become a radiant king whose commands are obeyed by nations. The Time Tantra thus reveals itself to be a means of “conquering” the world, not just spiritually but also in power political terms; in the end the imperial idea of a Chakravartin includes the whole universe. Boundlessly expanding energies are accumulated here in a single being (the “political” ADI BUDDHA).

The eminently political character of the Indian Chakravartin makes him an ideal for Tibetan Lamaism, which could first be realized, however, in the person of the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617-1682). Before the “Great Fifth” ascended the throne, the arch-abbots of the individual Lamaist sects — whether voluntarily or by necessity aside — accorded the title of world ruler only to the mighty Chinese Emperors or, depending on the political situation, to individual Mongolian Khans. The

Tibetan hierarchs themselves “only” claimed the role of a Buddha, an enlightened being, whom they nonetheless considered superior to the Chakravartin. The Fifth Dalai Lama, who combined in his person both worldly and spiritual power for the first time in the history of Tibet, was also still careful about publicly describing himself as Chakravartin. This could have provoked his Mongolian allies and the “Ruler on the Dragon Throne” (the Emperor of China). Such restraint was a part of the diplomacy of the Tibet of old; or rather, since the Dalai Lamas were during their enthronement handed the highest symbol of universal rule — the “golden wheel” — they were the “true”, albeit hidden, rulers of the world, at least in the minds of the Tibetan clergy. The worldly potentates of neighboring states were at any rate accorded the role of a protector.

We shall come to speak in detail about whether such cosmocratic images still excite the imagination of the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama in the second part of our study. In any case, the Kalachakra Tantra which he has placed at the center of his ritual politics contains the phased initiatory path at the end of which the Lion Throne of a Chakravartin rears up.

The “golden wheel” (chakra) is regarded as the world ruler’s coat of arms and gave him his name, which when translated from Sanskrit means “wheel turner”. Already at birth a Chakravartin bears a signum in the form of a wheel on his hand and feet as graphic proof of his sovereignty. In Buddhism the wheel symbol was originally understood to be the “teaching” (the Dharma) and the first “wheel turner” was no lesser than the Buddha himself, who set the “wheel of Dharma” in motion by distributing his truths among the people and among the other beings. Later, in Mahayana Buddhism, the golden wheel already indicated “The Great Circle of Power and Rule” (Simpson, 1991, p. 45). The Chakravartin was referred to as the “King of the Golden Wheel”. This is the title given to the “Emperor of Peace”, Ashoka (273–236 B.C.E.), after he had united India and with great success converted it to Buddhism; but is also a name which the Dalai Lama acquires when the “golden wheel” is presented to him during his enthronement.

A Buddhist world ruler grasps the “wheel of command”, symbol of his absolute force of command. In the older texts the stress is primarily on his military functions. He is the supreme commander of his superbly armed forces. As “king and politician”, the Chakravartin is a sovereign who reigns over all the states on earth. The leaders of the tribes and nations are subordinate to him. His epithet is “one who rules with his own will, even the kingdoms of other kings” (quoted by Armelin, n.d., p. 8). He is thus also known as the “king of kings”. His aegis extends not just over humanity, but likewise over Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, wrathful kings, gods, demons, nagas (snake gods), masculine and feminine deities, animals and spirits. Of his followers he demands passionate devotion to the point of ecstasy.

The seven “valuable treasures” which are available to a Chakravartin are (1) the wheel, (2) the wish-granting jewel, (3) the wonder horse, (4) the elephant, (5) the minister, (6) the general, and (7) the princess. Sometimes, the judge and the minister of finance are also mentioned. [3]

Opinions differ from text to text about the spatial expansion of power of the Chakravartin. Sometimes he “only” controls our earth, sometimes — as in the Kalachakra Tantra — the entire universe with all its suns and planets. This is — as we have already shown — described in the Abhidharmakosha, the Buddhist cosmology, as a gigantic wheel with Meru the world mountain as its central axis. The circumference is formed by unscaleable chains of mountains made of pure iron, from whence the name of this cosmic model is derived — Chakravala, that is, ‘iron wheel’. The Chakravartin is thus sovereign of an “iron wheel” of astronomical proportions.

In terms of time, the Buddhist writings nominate varying lengths of reign for the Chakravartin. In one text, as a symbol of control the supreme regent carries in his hand a golden, silver, copper, or iron wheel depending upon the eon (Simpson, 1991, p. 270). This corresponds to the Indo-European division of the ages of the world in which these become increasingly short and “worse” nearer the end. For this reason, world rulers of the golden age reign many millions of years longer than the ruler of the iron age. The Chakravartin also represents the Kalachakra deity, he is the bearer of the universal “time wheel” and hence the “Lord of History”.

As lawmaker, he monitors that human norms stay in keeping with the divine, i.e., Buddhocratic ones. “He is the incarnate representation of supreme and universal Law”, writes the religious studies scholar, Coomaraswamy (Coomaraswamy, 1978, p. 13, n. 14a). As a consequence, the world ruler governs likewise as “protector” of the cosmic and of the sociopolitical order.

As a universal guru he sets the “wheel of the teaching” (Dharmachakra) in motion, in memory of the famous sermon by the historical Buddha in the deer park of Benares, where the “first turning of the Wheel of the Word” took place (Coomaraswamy, 1979, p. 25). As a consequence, the Chakravartin is the supreme world teacher and therefore also holds the “wheel of truth” in his hands. As cosmic “wheel turner” he has overcome the “wheel of life and death” through which the unenlightened must still wander.

In the revolutionary milieu of the tantras (since the fourth century C.E.), the political, war-like aspects of the “wheel turner” known from Hinduism became current once more, to then reach — as we shall see — their most aggressive form in the Shambhala myth of the Kalachakra Tantra. The Chakravartin now leads a “just” war, and is both a Buddha (or at least a

Bodhisattva) and the glorious leader of an army in one person. The “lord of the wheel” thus displays clear military political traits. As the emblem of control the “wheel” also symbolizes his chariot with which he leads an invincible army. This army conquers and subjugates the entire globe and establishes a universal Buddhocracy. The Indian religious scholar, Coomaraswamy, also makes reference to the destructive power of the wheel. Like the discus of the Hindu god Vishnu, it can shave off the heads of the troops of entire armies in seconds.

Destruction and resurrection are thus equally evoked by the figure of the Chakravartin. He therefore also appears at the intersection of two eras (the iron and the subsequent golden age) and represent both the downfall of the old and the origin of the new eon. This gives him marked apocalyptic and messianic characteristics. He is incarnated as both world destroyer and world redeemer, as universal exterminator and universal savior.

Profane and spiritual power

The history of India, just like that of medieval Europe, is shaped by the clash between spiritual and worldly power. “Pope” and “Emperor” also opposed one another on the subcontinent in the form of Brahman and King, the battle between sacerdotium (ecclesiastical rule) and regnum (kingly rule) was also a recurrent political topic in the India of old. Interestingly, this dispute is regarded in both the Occident and in Asia as a gender conflict and the two sex roles are transferred onto the two pretenders to power. Sometimes the king represented the masculine and the priest the feminine, on other occasions it was the reverse, depending on which political party currently had the say.

This long-running topic of the “political battle of the sexes” was picked up by the intellectual elite of European fascism in the thirties of this century. The fascists had an ideological interest in conceding the primary role in the state and in society to the warrior type and thus the monarchy. It was a widespread belief at that time that the

hypocritical and cunning priestly caste had for centuries impeded the kings in their exercise of control so as to seize power for themselves. Such warrior-friendly views of history influenced the national socialist mythologist, Alfred Rosenberg, just as they did the Italian Julius Evola, who for a time acted as “spiritual” advisor to Mussolini. Both believed the masculine principle to be obviously at work in the “king” and the inferior feminine counterforce in the “priest”. “The monarchy is entitled to precedence over the priesthood, exactly as in the symbolism [where] the sun has precedence over the moon and the man over the woman “, Evola wrote (Evola, 1982, p. 101).

The Indian philosopher of religion, Ananda Coomaraswami, answers him with a counter-thesis: originally the king was “unquestionably feminine” and the priest masculine: “The sacerdotium and the man are the intellectual, and the regnum and the woman the active elements in what should be literally a symphony” (Coomaraswamy, 1978, p. 6). Thus we find here the conception, widespread in

India, that the feminine is active, the masculine passive or contemplative, and that control can be exercised through meditation (such as through holding the breath). In this we are confronted with the view that the practice of yoga is transferable to politics. Such a conception is in fact characteristic of Hinduism. In Tantric Buddhism, however, the order is reversed, as it is in the West: the goddess is passive and the god active. For this reason the fascist, Julius Evola, for whom the heroic masculine principle is entitled to the royal throne, was much more strongly attracted to Buddhist Vajrayana than to the Hindu tantras.

But when the sacerdotium unites with the regnum in one person, as in the case of the Dalai Lama, then the two celebrate a “mystic wedding”. The powers of the two forces flow together in a great current out of which a universal “wheel turner”, a Chakravartin arises, who has condensed within himself the masculine and feminine principle, worldly and priestly power, and is thus capable of exercising supreme control. Ananda Coomaraswamy has emotionally described this exceptional situation with the following words: “It is, then, only when the priest and the king, the human representatives of sky and earth, God and his kingdom, are ‘united in

the performance of the rite’, only when ‘thy will is done on earth as it is in heaven’, that there is both a giving and a taking, not indeed an equality but a true reciprocity. Peace and prosperity, and fullness of life in every sense of the words, are the fruits of the ‘marriage’ of the temporal power to the spiritual authority, just as they must be of the marriage of the ‘woman’ to the ‘man’ on whatever level of reference. For ‘verily, when a mating is effected, then each achieves the other’s desire’; and in the case of the ‘mating’ of the sacerdotium and the regnum, whether in the outer realms or within you, the desire of the two partners are for ‘good’ here and hereafter” (Coomaraswamy, 1978, p. 69). The marriage of the masculine and the feminine principle, which here forms the foundation for absolute political power, shows the Chakravartin to be an androgyne, a bisexual superhuman.

Neither Coomaraswamy nor Evola appear to have the slightest doubts about according feminine energies to masculine individuals and institutions in their theories. For this reason, the patriarchal power visions of Tantrism are as obvious in the two authors’ interpretations of history as they otherwise only are in the original Tibetan texts. Since for Coomaraswamy the feminine is incarnated in the “king”, and as such may never rule alone, the religious philosopher considers the autonomous power of the kings to be the origin of evil: “But, if the King cooperating with and assimilated to the higher power is thus the

Father of his people, it is none the less true that satanic and deadly possibilities inhere in the Temporal Power: When the Regnum pursues its own devices, when the feminine [!] half of the Administration asserts its independence, when Might presumes to rule without respect for Right, when the ‘woman’ demands her ‘rights’[!], then these lethal possibilities are realised; the King and the Kingdom, the family and the house, alike are destroyed and disorder prevails. It was by an assertion of his independence and a claim to ‘equal

rights’ that Lucifer fell headlong from Heaven and became Satan, the ‘enemy’” (Coomaraswamy, 1978, p. 69). The equation of the feminine with the epitome of evil is here no less clear and crass than it is in the work of the fascist, Julius Evola, who interprets our “unhappy” age as the result of a “gynocracy” which was prepared by the priests of the various religions.

That the role of the Chakravartin is reserved exclusively for men must be a self-evident assumption in the light of what has been said above. In a very early Buddhist text we already find this succinct formulation:

It is impossible and can not be

that the woman a Holy One, a Completely Awakened [One]

or a King World-Conqueror (Chakravartin) may embody:

such a case does not occur.

(quoted by Herrmann-Pfand, 1992, p. 172)

Footnotes:

[1] As we have already seen , the world mountain itself with its surrounding cosmic circles possesses the form of a huge mandala.

[2] However, the actual marking up of the diagram is carried out with a cord coated in chalk powder, which is placed in particular directions on the ritual table. With a brief pluck upon this cord the powder is transferred to the surface and forms a line there. Together, all the lines sketch the pattern of the sand mandala foundations.

[3] Where his golden wheel, (1), appears on the horizon the Buddhist teaching is spread. “This wheel has a thousand rays. The monarch who possesses it is called ‘the Holy King who causes the wheel to turn’, because from the moment of his possessing it, the wheel turns and traverses the universe according to the thoughts of the king” (Simpson, 1991, p. 269). Thanks to the wish-granting jewel, (2), the world ruler need only raise his hand and gold coins start to rain down (Coomaraswamy, 1979, fig. 19). The wonder horse, (3), transports him anywhere in next to no time. The elephant, (4), is obedient and represents the workforce among his subjects. The minister, (5), has no ulterior motives and stands by him with moral and tactical support. The general, (6), has the power to defeat all enemies. The body of the princess, (7), smells of sandalwood and from her mouth comes the scent of the blue lotus. She performs the functions of a royal mother: “Contact with her provokes no passions; all men regard her as their mother or sister. ... She gives birth to many sons [!]. When her husband is absent (she maintains chastity) and never succumbs to the pleasures of the five senses” (Tayé, 1995, p. 136). — With the following seven “semi-valuable” treasures it becomes even clearer how the magic political objects of the Chakravartin coincide with those of the tantric Maha Siddha (Grand Sorcerer): (1) the sword, which defends the king’s laws; (2) a tent which withstands any weather; (3) a palace full of goddesses playing music; (4) a robe impenetrable for any weapon and immune against fire; (5) a garden of paradise full of wondrous plants and animals; (6) a sleeping place which repels all false emotions and dreams and produces a clear awareness; and (7) a pair of seven league boots with which any point in the universe can be reached in a flash. </poem>