The three Kaya's

THE FRUITION OF BUDDHIST PRACTICE is the realization of the three kayas--Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya, and Nirmanakaya. These are the three bodies of Buddha's being or enlightenment. Dharmakaya corresponds with one's mind, Sambhogakaya with one's speech, and Nirmanakaya with one's body. Dharmakaya is the formless body. It is an undifferentiated state of being which we cannot talk about in terms of either confusion or enlightenment.

The Dharmakaya is something that is always present; it is rediscovered rather than created anew. Because it is atemporal and ahistorical, we cannot attribute change or transformation to it. Because it is passive and indeterminate in nature, Dharmakaya cannot manifest as a medium for one to work for the benefit of others, but it does give rise to the deterministic aspects of Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya.

Like the Dharmakaya, the Sambhogakaya is always present. It has to do with mental powers, with the ability of one's mind to manifest in relation to the five wisdoms. In tantric practice, all deities are manifestations of Sambhogakaya because they embody the five different types of wisdom. The Sambhogakaya is connected with communication, both on the verbal and nonverbal levels, and it is also associated with the idea of relating, so that speech here means not just the capacity to use words but the ability to communicate on all levels. Both the Sambhogakaya and Dharmakaya aspects are already embodied within each sentient being, and fruition is a matter of coming to that realization.

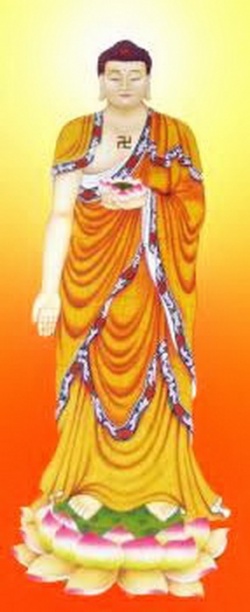

Nirmanakaya is the physical aspect of an enlightened being, the medium through which communication and relating can be carried out. It can be said to be new or different, because it is only on the physical level that one can become transformed. In Tibetan the purified body, called ku, is the manifestation of the fully transformed body free from the influence of deeply set and inculcated karmic residues.

Our ordinary physical body is called lu. It is the product of karmic traces and dispositions, and it is lacking in spontaneity and creativity. Through the purification of one's body, speech, and mind, the physical body ceases to be a locus for undesirable negative tendencies, excessive desires, and obsessions, and instead becomes the Nirmanakaya, a medium with extraordinary power to work with and benefit others.

The idea of three bodies should not mislead us into thinking that there are three different entities. Dharmakaya and Sambhogakaya do not refer to entities so much as existential states of being, and only the Nirmanakaya body is created anew in physical form. Actually the three kayas are two bodies--the formless body and the body of form. Both the Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya are normally called the form bodies of the Buddha, while Dharmakaya is formless.

Dharmakaya is basically the embodiment of what is called twofold purity. In its primordial purity, Dharmakaya is completely empty and open, and it has never been corrupted by emotional conflicts or conceptual confusions. The second aspect, the temporary aspect of the twofold purity of the Dharmakaya, appears as the result of working with one's emotions on the path, when a practitioner begins to become cleansed.

When one embarks on the path by purifying oneself in this way, then one can also manifest in Sambhogakaya form. In tantric practice it is one's own Sambhogakaya energy that one is trying to invoke, and tantric teachings should be understood as being present within the mind itself, in Sambhogakaya form. But Sambhogakaya is not something that can be perceived by ordinary beings, for one needs to have a purified mind both to perceive it and to communicate it.

A person may manifest all kinds of mental powers, but if the audience is limited in its capacity and the people subject to all kinds of illusions, then they will not be able to appreciate the manifestation of Sambhogakaya. The Buddhas always communicate through the Nirmanakaya aspect, expressing themselves verbally and mentally, because they can best work for the benefit of others through such physical means.

However, the three kayas are not completely independent of each other. They are always interrelated, and when they unfold fully, they are inseparable from each other. The Nirmanakaya and the Sambhogakaya basically manifest out of Dharmakaya; in other words, both of the form aspects of the Buddha's being are dependent on the formless body. The Dharmakaya is the origin or field on which the other two are grounded.

When we call the Sambhogakaya a "form body," we do not mean physical form but instead form in the sense of manifesting and being determinate, as opposed to Dharmakaya, which is formless because it is not determinate. The Sambhogakaya is determinate because, although it is not physical, it does manifest in varieties of ways. If Sambhogakaya is fully realized, then one can receive different teachings and meanings from many natural sources, such as sound, sight, and so on.

Sambhogakaya in turn gives rise to Nirmanakaya, which is realized through the physical body, and embodies both the Sambhogakaya and the Dharmakaya aspects. Nirmanakaya is physical in its essence and is historically situated, so that when we talk about Buddha Shakyamuni attaining enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, giving teachings in Varanasi, and eventually attaining paranirvana in Kushinagar, we are describing his Nirmanakaya aspect.

Because the Buddha's Sambhogakaya and Dharmakaya aspects are not historically situated, we cannot attribute any kind of temporality to them. The Sambhogakaya teachings are not a personal matter, and in some sense they cannot even be said to be Buddhist. The Sambhogakaya has embodied its meanings right from the beginning, before the time of the Buddha. It embodies them now, and it will embody them again in the future, for the auspicious coincidence of time is never ceasing.

The iconographical figure of the Vajradhara in thangkas and elsewhere symbolizes the Sambhogakaya aspect in its primordial sense. Vajradhara means "holder of the vajra scepter," and the vajra signifies the perennial truthfulness of reality that is not subjected to change and that does not need to be updated. Like the vajra, truth cannot be relativized and made into something that is conditional. It is a reality that is perennially true. As the symbol of Sambhogakaya, Vajradhara is an ahistorical phenomenon and is perceptible only to people with extraordinarily lucid and perceptive minds.

It is said that the Sambhogakaya manifests not in any kind of spatial or physical location but in a place that is not really a place; a place of nowhere called Akanishtha, or wok ngun in Tibetan. Wok mi means "not underneath," suggesting that Akanishtha, because it is a field of nowhere, is all encompassing. Ultimately wok-ngun refers to emptiness, or sunyata.

The teacher who manifests Sambhogakaya in the place called Akanishtha is the Nirmanakaya Vajradhara, and he embodies not the ordinary teachings of the three yanas, but the most essential teachings of supreme Tantrayana that are always meaningful regardless of the historical situation. The audience to this level of teachings would be only realized advanced beings.

At the same time, from the point of view of the Nirmanakaya, we can say that the Buddha was born in such and such a place, and he went through such and such a practice, and when eventually he attained nirvana, he introduced the three yanas and other teachings. In that context the audience would include beings of varying capacities, dispositions, and inclinations.

The Sambhogakaya is called long cho dzok pai ku in Tibetan. Long cho means to make use of, to indulge. Because ku denotes purification of being in the Nirmanakaya, long cho dzok pai ku means "to make use of the transformed body. " The Sambhogakaya is called this because it is always immersed in a state of unceasing bliss. We can make the distinction between Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya from the outside, but in terms of the experience of the Buddha himself, we cannot talk about the Sambhogakaya manifesting first and Nirmanakaya afterwards. Ultimately we cannot talk in terms of one aspect of the kayas being superior and the other inferior.

The Sambhogakaya aspect is endowed with what are called the Five Auspicious Coincidences. First is the auspicious coincidence of the place, which is that the Sambhogakaya manifests in the place of Akanishtha. Second is the emergence of the teacher, in this case the Buddha in his Nirmanakaya aspect.

Third is the auspicious coincidence of the manifestation of the Sambhogakaya teachings as pure tantric manifestations. The teacher communicates these teachings not in terms of written scriptures but in terms of meaning. If practiced or realized, these essential teachings can deliver a person to the state of enlightenment in one lifetime.

The fourth auspicious coincidence is the convergence of a proper audience of bodhisattvas, dakas, and dakinis--those who are advanced on the path. Fifth is the auspicious coincidence of time. From the Sambhogakaya perspective, unlike the Nirmanakaya perspective, past, present, and future are simultaneously embodied in the teachings. For instance, in his Nirmanakaya aspect the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Noble Path, and so on. Because we can say that these Buddhist teachings began at a specific time, we might also speculate about when Buddhism might cease to exist. But the Sambhogakaya teachings are ever present and therefore unceasing.

The manifestation of the teacher in the form of Sambhogakaya has certain qualities, called the Seven Limbs. The first limb is that the Sambhogakaya aspect is fully immersed in Mahayana teachings. The second is called the limb of coexistence, which means that because the Sambhogakaya is never corrupted, it manifests in conjunction with wisdom. Third is the limb of fullness, which means that the Sambhogakaya aspect is full of truth, completely steeped in truth.

The fourth limb is the limb of nonsubstantiality, because the manifestation of the Sambhogakaya is lacking in inherent existence. Next is the limb of infinite compassion, for the Sambhogakaya aspect is fully imbued with compassionate concerns and it directs its attention toward other sentient beings. The sixth is the limb of noncessation, which means that the resonating concern for other sentient beings is ever present and there fore unceasing.

The seventh and last quality is called the limb of perennial manifestation, which means that the Sambhogakaya cannot cease to be, but has manifested throughout the ages. There is no such thing as Sambhogakaya ceasing to exist in the way that the Nirmanakaya is withdrawn when the Buddha enters paranirvana.

When one embarks on the path and works for the benefit of others by engaging in bodhisattva deeds and generating loving kindness and compassion, then one is sowing seeds for the attainment of the Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya aspects of the form body of the Buddha. Concurrent with kind and compassionate action, one's insight and wisdom increase. These qualities are the ones that can manifest eventually as the full unfolding of the formless aspect of buddha being, the Dharmakaya.

The relationship among the three kayas is like the relationship of the sky to the clouds and the rain. The sky corresponds to Dharmakaya, the clouds to Sambhogakaya, and the rain to Nirmanakaya. Just as space, or the sky, is not a conditional product, so the Dharmakaya does not come about because of causes and conditions; it is indeterminate. However, Dharmakaya gives rise to manifestations of Sambhogakaya in the same way as space gives rise to cloud formations.

The Tibetan text Ngu Dun Du Pa says that the state of Dharmakaya precedes the ideas of both confusion and wisdom. Before any dualistic notions have arisen, before one has experienced anything, this unconditional state is spontaneously arisen. It is a neutral state because it is neither positive nor negative, yet at the same time there is a presence of self-awareness. Because the state of Dharmakaya has never been corrupted by emotional conflicts or conceptual confusions, one cannot talk about it in terms of either nirvana or samsara.

In another text, Yeshe Ting Dzog, it states that, before we had any idea of Buddhas or sentient beings, there was a state that was absolutely pure and uncorrupted, as well as cognizant or self-aware. This state--Dharmakaya--is the state of nondifferentiation, and it is the basis or matrix for any experience. Whether one is a buddha or a being thrown into the turmoil of a hell realm, the presence of the substratum or matrix of Dharmakaya is the same, and this undifferentiated state is the basic source for all of our conscious experiences.

But Dharmakaya is a state, not an entity. It is not a thing. It is not a product of causes and conditions, and it is permanent. But to say that it is permanent does not mean that it endures forever, because Dharmakaya is not an entity--it is nothing. It can be said to be permanent because it is unconditional like the sky. Yet this unconditional state gives rise to all conditional things--all the experiences of samsara and nirvana, confusion and wisdom, conceptual perplexities, emotional conflicts, and so on.

These various experiences of the mind are also related to the Sambhogakaya aspect which may manifest from the nondifferentiated state of Dharmakaya as visions or visitations. For example, the Sambhogakaya manifested to the great teacher Naropa one day while he was going for a walk. As he was strolling along, Naropa bumped into the ugliest looking woman he had ever seen. She said to him, "Eh, what do you know about Buddhism?" He replied "I know quite a lot because I am a professor at Nalanda University. At that the ugly woman started to sing and dance, and Naropa was a bit puzzled. Then she asked him, "Well, do you know the meaning of the teachings?" Naropa quickly replied, "Yes," but when he said this the woman started to cry. Then something clicked, and Naropa realized that so far all that he understood was purely intellectual and conceptual, and he had completely forgotten to tune into his more intuitive aspects.

Naropa's vision of the ugly woman was, in a sense, a symbolic calling from the Sambhogakaya, some kind of revelatory experience, and one can have varieties of such experiences in terms of Sambhogakaya. It is said that the Sambhogakaya communicates in symbolic language. It manifests in such a way that one understands it not through words, descriptions, and explanations, but through a more intuitive response to one's experiences.

Visions and dreams--all of these--are part of that whole symbolic language of Sambhogakaya manifestation. For this reason, working with one's mind in relation to visualizations, deities, utterance of mantras, and so on, are ways to invoke the Sambhogakaya energy. If one is successful with this, then one can have different kinds of visions.

The Sambhogakaya can be characterized by the eight types of power and enrichment, known as wang chuk gye. The first type is called kui wang chuk, which means the power and enrichment of the body. It is said that the power of the body becomes such that all things of samsaric and nirvanic nature become completely subdued and one is able to take full charge of them. Along with this power, one is enriched with many positive qualities.

The second is sung gi wang chuk, the power and enrichment of the verbal capacity or speech. In this case the capacity of speech or communication is such that all the essential verbal elements of both samsaric and nirvanic qualities become assimilated, and one is able to make full use of them. Thus one becomes enriched and empowered.

The third is called thuk gyi wang chuk. Here the power of the mind in relation to both samsara and nirvana becomes assimilated and integrated, and one becomes empowered and enriched with all the different possibilities of mental manifestation.

Fourth is zung thrul kyi wang chuk, or the power of miracle, whereby the person's capacity of expression is such that he or she is not confined by the three gates of body, speech, and mind, but is able to go beyond conventional modes of expression, thus being able to display his or her power in unusual ways.

Fifth is kun du wang chuk, the ever-going, ever moving empowerment and enrichment. One is constantly being impelled toward action, toward the intention to act and to accomplish things for the benefit of others. So in terms of doing, or acting, one becomes fully endowed with varieties of powers related to samsaric and nirvanic qualities.

The sixth one is called ne gyi wang chuk, the enrichment and empowerment of place. This means that the Sambhogakaya is situated in Akanishtha, which is basically the sphere of reality. One becomes enriched and empowered in this sense because Sambhogakaya is inseparably united with reality, and all the powers related with that can manifest.

Seventh is de pai wang chuk, the empowerment and enrichment of sensuality. This is connected with the idea that Sambhogakaya is inseparably in unison with its female counterpart, whether one calls that the mother of all Buddhas or the selfless one, Dag mema--or whether one calls it Vajravarahi or Vajrayogini. Whatever one might call it, the female counterpart is continuously in unison with the Sambhogakaya, and this experience continuously produces the great bliss of being in unison, which is the Mahamudra expression as well. Finally, one is empowered and enriched by the capacities to manifest prajna or sherab.

The eighth and last type is called chin de pai wang chuk which means the enrichment and empowerment to fulfill one's wishes. Sambhogakaya is intrinsically endowed with all the worldly and supramundane boons. A worldly boon, or loka siddha, is the capacity to work with one's extrasensory capacities, such as clairvoyance, clear audience, telepathy, and so forth. The loka siddhi are the supernormal powers of different spiritual realizations.

When one becomes empowered and enriched by these eight types of empowerment, as well as the seven limbs discussed earlier, one reaches the state called Vajradhara, or "the holder of the vajra." The vajra symbolizes eternal truth, and dhara, or holding, means that one's mental continuum of Sambhogakaya is never separated from the ever present capacity to be in tune with reality. For that reason Vajradhara is the symbolic representation of the Sambhogakaya.

Once the Sambhogakaya is realized, then through the means of Nirmanakaya, one can manifest in many ways to benefit other beings. The two form bodies of the Buddha--Nirmanakaya and Sambhogakaya--are both directed toward helping others, because when one gives birth to enlightenment, one is then automatically moved and impelled to work for the benefit of others.

In the interrelationship of the three kayas, we have seen that Dharmakaya is basically the source--the matrix or the ground--from which all our experiences manifest. The Sambhogakaya emerges out of the Dharmakaya and if one is able to tune into the Sambhogakaya, then one is able to manifest in Nirmanakaya form.

There are three different kinds of Nirmanakaya. Zoye tulku means Nirmanakaya of artifacts, such as statues and other sacred artifacts that manifest and are venerated as religious objects. Kye wai tulku means Nirmanakaya of birth and refers to highly evolved beings who continue to reincarnate in Nirmanakaya form for the benefit of others. This is why the tulkus are called tulkus. Finally, chul ku tulku in the Nirmanakaya of the absolute. This means that the person has fully realized Buddhahood, and has attained full enlightenment.

It is said that a fully enlightened being is automatically impelled to work for the benefit of others. But how does this come about? It is said that a buddha has overcome all dualistic notions, such as the distinction between the object of compassion and the agent who practices compassion, yet if he or she sees sentient beings as objects of compassion, is he not still subjected to dualistic notions? There really is no contradiction here, because although the buddha is aware of sentient beings as objects of compassion, this awareness does not give rise to conceptual proliferation, and therefore compassion is not generated from dualistic thoughts.

Nirmanakaya and Sambhogakaya manifest in a compassionate way through four major modes. The first mode is called the "ever present manifestation of compassion," which means that compassion is inherent in the realization of the Sambhogakaya. This compassion has always been here, and because it is ever present, it is inexhaustible at the Sambhogakaya level. So even if the buddha passes into paranirvana--even if the Nirmanakaya stops manifesting for a while--the manifestation of compassion does not cease on the Sambhogakaya level.

For instance, in the sutra it is said that, from the Sambhogakaya point of view, Buddhas do not pass into paranirvana and dharmas do not cease to be propounded. The teachings continue to be embodied in the Sambhogakaya experience. The Nirmanakaya form manifests and dissolves in order to benefit sentient beings who are subject to laziness, but on the Sambhogakaya level, there is no such coming into being or going out of existence. Compassion is ever present.

The second mode is called rang zhin gyi shug gyi kye wai thug je, which means "compassion which manifests spontaneously, without being elicited." The way in which this compassion manifests can be expressed by the phrase "resonating concern." Within a particular situation, compassion arises automatically without any judgment or conceptual interpretation. It manifests if there is a need for it, like the sun illuminating the darkness, or the moon being reflected in the water. In this way also compassion is ever present, and it manifests spontaneously.

The third mode is called yul den te ne thug je che wa or "compassion of meeting the appropriate object." This means that those able to respond to the Sambhogakaya manifestation receive that benefit, and those can who respond to the Nirmanakaya aspect get that particular benefit. The object of compassion and the kind of compassion received are congruent or correspond with each other. The compassion of the Sambhogakaya and the compassion of the Nirmanakaya each manifest in appropriate ways, depending on the type of beings present. Thus, different beings with different dispositions and predilections can receive compassion no matter what, depending on their levels of understanding and evolution.

The fourth mode is called the "manifestation of compassion that has been elicited." Sol wa de pa basically means "requested of," and it is said that this compassion has two aspects: eliciting the compassionate response in a general way, and eliciting it in a more specific way. Eliciting the compassionate response in a general way means that when the Sambhogakaya manifests in emptiness, then all of a sudden a being becomes moved with compassion. The more specific way occurs in actual situations in this particular world. For instance, when the Buddha attained enlightenment, he did not automatically start to teach, but he was requested to teach and work for the benefit of others. It is said that if one requests compassion from the lama or yidam, them one receives compassion manifesting in a specific way.

These four modes of compassion manifest in relation to both Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya; their by-product is the manifestation of compassion in the public arena through the medium of Nirmanakaya. This in turn takes the form of teachings given by enlightened beings, because it is said that the ultimate compassionate act is to impart teachings. From a Buddhist point of view, teachings have two aspects: One is called ka, which is the teaching that Buddha, for example, gave from his own mouth. The other aspect is ten gyur, which consists of commentaries based upon the Buddha's own teachings.

Further, the teachings called ka, or the Buddha's own utterances, have three aspects: The first, shal nay sum pe ka, are the teachings given by the Buddha himself. The second, jin gyi lap pe ka, are teachings given with the Buddha's blessing and in his presence. When the Buddha encouraged or inspired someone else, such as Avalokiteshvara, to act as his mouthpiece, such a teaching had the same authority as if it were given by the Buddha, and such teachings are also called ka . Finally, we have je su nang we ka, which means teachings that are bequeathed to later generations. These teachings were not presented while Buddha was alive, but were invoked and, in a sense, rediscovered and given a new impetus for another generation by the Buddha himself.

Now the ten gyur, or the commentaries, are teachings that are embodied, and they all have two aspects: One is the doctrinal aspect, and the other is the experiential aspect, and these two must correspond. In other words, if one has studied and learned something intellectually, those teachings must correspond with inner experiences. As far as the teachings themselves are concerned, there is not one single thing that we can call the standard presentation of Buddhism, because the Buddha, in his infinite wisdom and compassion, and through his exercise of skillful means, was able to devise many methods and many interpretations.

The teachings that come to be known as the Dharma or Buddhism cannot be encapsulated within one particular format. There are many levels of interpretation and many levels of understanding. As Nagarjuna says, "The Dharma of the Buddha is immense, like the ocean. Depending on the aptitudes of beings, it is expounded in various ways. It can speak of existence or nonexistence; eternity or impermanence; happiness or suffering; the self or not self." He goes on to say, "Such are the manifold and diverse teachings."

The point that Nagarjuna is making is that in the early Hinayana teachings, which were the first turning of the wheel of Dharma, the Buddha negated the existence of a permanent, substantial self, but he did not go into an elaborate discussion of emptiness. In the second turning of the wheel of Dharma, the teachings on the emptiness of phenomena were introduced, along with the idea of the nonsubstantiality or emptiness of the personality of self. Then in the third turning of the wheel of Dharma, the idea of tathagatagarbha or Buddhanature was introduced. According to this doctrine, even if there is no such thing as self, ego, or soul, nonetheless there is an element of incorruptible spiritual principle called tathagatagarbha, or Buddhanature, that cannot be vitiated and that cannot yield to passions and other confusions.

In this way different levels of teachings were given, including the tantras, that may seem to contradict each other and may even seem to be in direct opposition to each other's propositions. But it is said that teachings are presented in different way because they have to reach the widest possible number of people. For the most people to benefit, the teachings must be presented in various ways appropriate to various aptitudes, dispositions, and intellectual levels. This is why the Buddha's teachings can be understood on many different levels.

In the Mahayana, to separate the essence of the teachings from what is peripheral or superficial to them, a distinction is made between interpretive teachings and definitive teachings. The interpretive teachings are called drang don. Drang means to liberate others. Such teachings should not necessarily be taken literally, but they do have their own function. For example, there are all kinds far fetched, incredible stories told in the sutras and elsewhere about the miraculous activities of bodhisattvas. These are interpretive teachings be cause they are told in order to inspire people. Teachings such as these should be taken only interpretively, not definitively.

From the Mahayana point of view, the definitive teachings are the ones concerned with emptiness, and all discourses on emptiness should be taken ultimately. But there is a problem here. Among the different schools of Buddhism there is no agreement as to what is really interpretive, and what is really definitive. In Tibetan Buddhism, for example, the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages regard the tathagatagarbha teachings presented in the third turning of the wheel of the Dharma as ultimate teachings. However, the Gelugpas say that the teachings on Buddhanature cannot be taken as definitive because tathagatagarbha theory is given so that people will not "freak out" if they are told they do not have a substantial ego. The Gelugpas introduce the idea of tathagatagarbha, but they say that it has only interpretive and not definitive meaning.

In any case, all the varieties of teachings, as complex as they may be, are given in order to alleviate people's neurosis, and it is said that there are 84,000 different types of teachings corresponding to 84,000 neuroses. However one may interpret them, the teachings are given to alleviate suffering and emotional conflicts.

In contrast to the Sambhogakaya activity of communication through symbols, the Nirmanakaya form presents teachings in nonsymbolic language that uses the literal meaning of words. In this way many people can benefit from it. The fulfillment of the Nirmanakaya is that it manifests in order to impart teachings that can be followed and studied.

This teaching was given by the Ven. Traleg Rinpoche in November 1989 at Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, Woodstock, New York, and edited for Densal by Sally Clay.