Sky burial

Sky burial (Tibetan: བྱ་གཏོར་, w bya gtor), lit. "alms for the birds") is a funerary practice in the Chinese provinces of Tibet, Qinghai,

and Inner Mongolia and in Mongolia proper wherein a human corpse is incised in certain locations and placed on a mountaintop, exposing it to the elements (mahabhuta) and animals – especially predatory birds.

The locations of preparation and sky burial are understood in the Vajrayana traditions as charnel grounds.

The majority of Tibetans and many Mongolians adhere to Vajrayana Buddhism, which teaches the transmigration of spirits. There is no need to preserve the body, as it is now an empty vessel.

Birds may eat it or nature may cause it to decompose.

The function of the sky burial is simply to dispose of the remains in as generous a way as possible (the source of the practice's Tibetan name).

In much of Tibet and Qinghai, the ground is too hard and rocky to dig a grave, and, due to the scarcity of fuel and timber, sky burials were typically more practical than the traditional Buddhist practice of cremation.

In the past, cremation was limited to high lamas and some other dignitaries, but modern technology and difficulties with sky burial have led to its increasing use by commoners.

History and development

The Tibetan sky-burials appear to have evolved from ancient practices of defleshing corpses as discovered in archeological finds in the region.

These practices most likely came out of practical considerations, but they could also be related to more ceremonial practices similar to the suspected sky burial evidence found at Göbekli Tepe (11,500 years before present) and Stonehenge (4,500 years BP).

Most of Tibet is above the tree line, and the scarcity of timber makes cremation economically unfeasible.

Additionally, subsurface interment is difficult since the active layer is not more than a few centimeters deep, with solid rock or permafrost beneath the surface.

The customs are first recorded in an indigenous 12th-century Buddhist treatise, which is colloquially known as the Book of the Dead (Bardo Thodol).

Tibetan tantricism appears to have influenced the procedure.

Dissection occurs according to instructions given by a lama or adept.

Mongolians traditionally buried their dead (sometimes with human or animal sacrifice for the wealthier chieftains) but the Tümed adopted sky burial following their conversion to Tibetan Buddhism under Altan Khan during the Ming Dynasty and other banners subsequently converted under the Manchu.

Sky burial was initially treated as a primitive superstition and sanitation concern by the Communist governments of both the PRC and Mongolia;

both states closed many temples and China banned the practice completely from the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s until the 1980s.

Sky burial nonetheless continued to be practiced in rural areas and has even received official protection in recent years.

However, the practice continues to diminish for a number of reasons, including restrictions on its practice near urban areas and diminishing numbers of vultures in rural districts.

Where the vultures remain, they often react badly to corpses treated with medicine and disinfectants at modern hospitals.

Finally, Tibetan practice holds that the yak carrying the body to the charnel grounds should be set free, making the rite much more expensive than a service at a crematorium.

Purpose and meaning

For Tibetan Buddhists, sky burial and cremation are templates of instructional teaching on the impermanence of life.

Jhator is considered an act of generosity on the part of the deceased, since the deceased and his/her surviving relatives are providing food to sustain living beings.

Such generosity and compassion for all beings are important virtues in Buddhism.

Although some observers have suggested that jhator is also meant to unite the deceased person with the sky or sacred realm,

this does not seem consistent with most of the knowledgeable commentary and eyewitness reports, which indicate that Tibetans believe that at this point life has completely left the body and the body contains nothing more than simple flesh.

Only people who directly know the deceased usually observe it, when the excarnation happens at night.

Vajrayana iconography

The tradition and custom of the jhator afforded Traditional Tibetan medicine and thangka iconography with a particular insight into the interior workings of the human body.

Pieces of the human skeleton were employed in ritual tools such as the skullcup, thigh-bone trumpet, etc.

The 'symbolic bone ornaments' (Skt: aṣṭhiamudrā; Tib: rus pa'i rgyanl phyag rgya) are also known as "mudra" or 'seals'.

The Hevajra Tantra identifies the Symbolic Bone Ornaments with the Five Wisdoms and Jamgon Kongtrul in his commentary to the Hevajra Tantra explains this further.

A traditional jhator is performed in specified locations in Tibet (and surrounding areas traditionally occupied by Tibetans). Drigung Monastery is one of the three most important jhator sites.

The procedure takes place on a large flat rock long used for the purpose.

The charnel ground (durtro) is always higher than its surroundings. It may be very simple, consisting only of the flat rock, or it may be more elaborate, incorporating temples and stupa (chorten in Tibetan).

Relatives may remain nearby during the jhator, possibly in a place where they cannot see it directly. The jhator usually takes place at dawn.

The full jhator procedure (as described below) is elaborate and expensive. Those who cannot afford it simply place their deceased on a high rock where the body decomposes or is eaten by birds and animals.

Accounts from observers vary. The following description is assembled from multiple accounts by observers from the U.S. and Europe. References appear at the end.

Participants

Prior to the procedure, monks may chant mantra around the body and burn juniper incense – although ceremonial activities often take place on the preceding day.

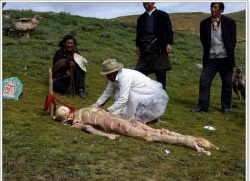

The work of disassembling of the body may be done by a monk, or, more commonly, by rogyapas ("body-breakers").

All the eyewitness accounts remarked on the fact that the rogyapas did not perform their task with gravity or ceremony, but rather talked and laughed as during any other type of physical labor.

According to Buddhist teaching, this makes it easier for the soul of the deceased to move on from the uncertain plane between life and death onto the next life.

Disassembling the body

According to most accounts, vultures are given the whole body.

Then, when only the bones remain, these are broken up with mallets, ground with tsampa (barley flour with tea and yak butter, or milk), and given to the crows and hawks that have waited for the vultures to depart.

In several accounts, the flesh was stripped from the bones and given to vultures without further preparation; the bones then were broken up with sledgehammers, and usually mixed with tsampa before being given to the vultures.

Many rogyapa first feed the bones and cartilage to the vultures, keeping the best flesh until last.

After having had their fill of good quality meat, the birds usually fly away - leaving the bones and less favored bits.

In one account, the leading rogyapa cut off the limbs and hacked the body to pieces, handing each part to his assistants, who used rocks to pound the flesh and bones together to a pulp, which they mixed with tsampa before the vultures were summoned to eat.

Sometimes the internal organs were removed and processed separately, but they too were consumed by birds.

The hair is removed from the head and may be simply thrown away; at Drigung, it seems, at least some hair is kept in a room of the monastery.

None of the eyewitness accounts specify which kind of knife is used in the jhator.

One source states that it is a "ritual flaying knife" or trigu (Sanskrit kartika), but another source expresses scepticism, noting that the trigu is considered a woman's tool (rogyapas seem to be exclusively male).

Vultures

The species contributing to the ritual is the "Eurasian Griffon," a species of Old World vulture (order Falconiformes, family Accipitridae, scientific name Gyps fulvus).

In places where there are several jhator offerings each day, the birds sometimes have to be coaxed to eat, which may be accomplished with a ritual dance. It is considered a bad omen if the vultures will not eat, or if even a small portion of the body is left after the birds fly away.

In places where fewer bodies are offered, the vultures are more eager- and sometimes have to be fended off with sticks during the initial preparations.

In popular culture

A jhator was filmed, with permission from the family, for Frederique Darragon's documentary Secret Towers of the Himalayas, which aired on the Science Channel in Fall 2008.

The camera work was deliberately careful to never show the body itself, while documenting the procedure, birds, and tools.

A discussion of "air burial" appears in issue 55 of Neil Gaiman's Sandman.

The ritual was featured in films such as Kundun and Himalaya.

Stupa burial and cremation are reserved for high lamas who are being honored in death.

Sky burial is the usual means for disposing of the corpses of commoners.

However, it is not considered suitable for children who are less than 18, pregnant women, or those who have died of infectious disease or accident.

The origin of sky burial remains largely hidden in Tibetan mystery.

Sky burial is a ritual that has great religious meaning. Tibetans are encouraged to witness this ritual, to confront death openly and to feel the impermanence of life.

They believe that the corpse is nothing more than an empty vessel.

The spirit, or the soul, of the deceased has exited the body to be reincarnated into another circle of life.

It is believed that the Drigung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism established the tradition in this land of snow, although there are other versions of its origin.

The corpse is offered to the vultures. It is believed that the vultures are Dakinis.

Dakinis are the Tibetan equivalent of angels.

In Tibetan, Dakini means "sky dancer". Dakinis will take the soul into the heavens, which is understood to be a windy place where souls await reincarnation into their next lives.

This donation of human flesh to the vultures is considered virtuous because it saves the lives of small animals that the vultures might otherwise capture for food.

Sakyamuni, one of the Buddhas, demonstrated this virtue.

To save a pigeon, he once fed a hawk with his own flesh.

After death, the deceased will be left untouched for three days.

Monks will chant around the corpse.

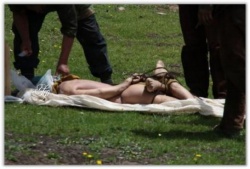

Before the day of sky burial, the corpse will be cleaned and wrapped in white cloth.

The corpse will be positioned in a fetal position, the same position in which the person had been born.

The ritual of sky burial usually begins before dawn.

Lamas lead a ritual procession to the charnel ground, chanting to guide the soul.

There are few charnel grounds in Tibet.

They are usually located near monasteries.

Few people would visit charnel grounds except to witness sky burials. Few would want to visit these places.

After the chanting, the body breakers prepare the body for consumption by the vultures.

The body is unwrapped and the first cut is made on the back.

Hatchets and cleavers are used to quickly cut the body up, in a definite and precise way.

Flesh is cut into chunks of meat.

The internal organs are cut into pieces. Bones are smashed into splinters and then mixed with tsampa, roasted barley flour.

As the body breakers begin, juniper incense is burned to summon the vultures for their tasks, to eat breakfast and to be Dakinis.

During the process of breaking up the body, those ugly and enormous birds circle overhead, awaiting their feast.

They are waved away by the funeral party, usually consisting of the friends of the deceased, until the body breakers have completed their task.

After the body has been totally separated, the pulverized bone mixture is scattered on the ground.

The birds land and hop about, grabbing for food.

To assure ascent of the soul, the entire body of the deceased should be eaten.

After the bone mixture, the organs are served next, and then the flesh.

This mystical tradition arouses curiosity among those who are not Tibetan.

However, Tibetans strongly object to visits by the merely curious.

Only the funeral party will be present at the ritual. Photography is strictly forbidden.

They believe that photographing the ritual might negatively affect the ascent of the soul.